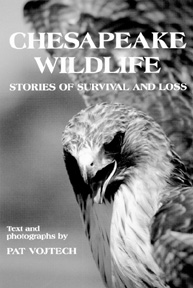

Pat Vojtech’s Chesapeake Wildlife

Pat Vojtech’s Chesapeake Wildlife

reviewed by Martha Blume

When Pat Vojtech was six years old, she sat on the front steps of her family’s home on the Eastern Shore and heard the Honk! Honk!” of a flock of Canada geese passing overhead. Not so remarkable, until her father pointed out that this everyday occurrence, part of the “fabric of my childhood,” as she relates it, was a rare sight some 60 years ago. No deer and no geese made the Chesapeake shores their home then, but black squirrels as big as cats roamed the woods and there were ducks, like the canvasbacks, now nearly gone from our waters.

So Vojtech wakened to the changing patterns of Chesapeake Bay wildlife over four centuries, the tale she tells with wisdom and sensitivity in her book Chesapeake Wildlife: Stories of Survival and Loss (Tidewater Publishers, 2001).

When Vojtech and her husband bought their own farm outside Centreville 22 years ago “in the midst of wildlife,” she began to see the shifts for herself.

“Though I grew up with it and learned a lot by watching, I knew that I didn’t know everything about wildlife,” she says. Her first motivation in writing her book was to educate herself; her second was to educate others.

“I realized that a lot of people moving into [the Chesapeake Bay region] didn’t realize how close we’ve come to losing the species we have today,” says the author. “If we could lose them once, we could lose them again.”

Chesapeake Wildlife reads like the best of stories, with plot, characters and the wonderful scenery of the Bay environs. “I couldn’t talk to the animals,” she laughs, “so I knew there would be very few quotes.” Instead — struck by how intelligent animals really are — she recreates scenes with animals in the lead roles.

The book begins in “a world unspoiled,” the Chesapeake Bay in the 1600s when Dabbling ducks by the hundreds scuttled through the maze of narrow waterways within the marsh. … Between the plants themselves and the life they supported, the marshes presented a smorgasbord for the birds and mammals that flocked to them by the thousands and the tens of thousands…

In subsequent chapters, we learn of the conflicts of human centuries: bounties on bears, wolves, fox squirrels and crows in the 1700s; farming with its associated agricultural wastes and the millinery trade in the 1800s; and clear-cutting, mining and DDT in the 1900s.

Vojtech weaves fascinating anecdotes into her telling, like ornithologist Frank Chapman’s 1866 survey of hats worn by upper-crust ladies in the New York City shopping district.

By 1904, a kilogram of feathers — which, as light as feathers are, required the killing of three hundred birds — was worth $32 an ounce or twice as much as gold of the same weight.

This amounted to about $3.74 per bird, about the same price elegant restaurants in New York were paying for a canvasback duck. Chapman determined that three out of four hats contained at least some bird plumes if not the entire corpse.

By the start of the 19th century, the Chesapeake had already seen its first great losses in wildlife populations. After thousands of years of uninterrupted fall migrations, the legendary “co-ho-co-ho” horn of the great trumpeters had been silenced on the Chesapeake. And the coveted white-tailed deer were all but gone.

But the story doesn’t end there. Vojtech also tells of heroes and defenders of wildlife, of legislation, of species reintroductions, of schoolchildren from her own Centreville Middle School’s Ecology Corps, of average citizens who protect backyard habitats for wildlife and of Geese in Space.

Vojtech grapples with the difficult issue of non-native animals. Of the Norway rat, which arrived with the Hessians in 1776, she says, “In the long run, the rats have proved far more harmful than the Hessian troops.” She also discusses today’s newsworthy mute swan.

“I wanted to point out why we have problems with non-natives and that there are lots of ways to deal with them rather than resorting to slaughter,” says Vojtech. “For me, there are three issues involved: species vs. man, species vs. the environment and species vs. species.”

Vojtech’s first love is photography, and it shows in the beautiful images that grace nearly every page of her text. She shows in some 25 art shows each year, most of them on the Eastern Shore.

Chesapeake Wildlife belongs in every bookshelf on both sides of the Bay, alongside Vojtech’s two other books, Lighting the Bay: Tales of Chesapeake Lighthouses (1996) and Chesapeake Bay Skipjacks (1993).

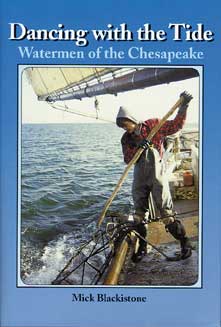

Dancing with the Tide: Watermen of the Chesapeake

Dancing with the Tide: Watermen of the Chesapeake

by Mick Blackistone • reviewed by Martha Blume

It’s early morning in Annapolis and Kenny Keen is doing a synchronized dance at the bar. Kenny’s feet move like Elton John’s across the foot pedals; his right hand adjusts the throttle and tiller to keep us drifting in the right direction and then reaches up to the patent tongs to pull them over the culling board or to send them back over the side. Kenny’s bar is an oyster bar and he an oyster tonger. His dance is one repeated over the centuries by watermen who, like him, make their living dancing with the tide.

Mick Blackistone’s chronicle Dancing with the Tide (Tidewater Publishers, 2001), paints a colorful mural of watermen’s lives on Chesapeake Bay in the 21st century. In this sequel to Sunup to Sundown (1989), native son Blackistone literally gets on board with crabbers and oyster tongers, fishermen and clammers to listen to their stories.

In frank conversations with Blackistone, the watermen consistently ask to be listened to. Beginning July 23, crabbers faced a shortened workday in a season that ended a month early, based on limits imposed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. That was followed by news that the Bay received a failing grade in the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s 2001 State of the Bay report, and announcements that the oystermen face a dismal harvest again this season.

In Dancing, we hear watermen’s perspective in the ongoing battle between the fisheries and conservationists, a battle in which the watermen often find themselves on the losing side.

One of these watermen is Bob Evans, who has worked the Bay for most of his life. “I’ll tell you the Bay is in good shape,” he asserts. “The fish industry is back, there’s some oysters, and while we didn’t have many crabs this past summer, we had more than we knew what to do with in the fall. I disagree with most of the fisheries managers and people from groups like the [Coastal Conservation Association] and [Chesapeake] Bay Foundation who are always crying wolf. … I don’t know why they don’t listen to us.”

The need for a voice in the management of the fisheries industries has led many watermen into politics. Ron Fithian was a clammer, fisherman and oysterman “when making $2-3,000 a week was the rule rather than the exception.” He left the fisheries for politics in the early ’90s when the market declined. Now town manager of Rock Hall, Maryland, he blames the state for destroying the fisheries. “They are constantly overcorrecting the problem instead of controlling it,” he told Blackistone.

Many watermen assert that overfishing is not the problem with decline in fisheries as much as disease, competition from recreational boaters and complicated environmental factors like the effects of drought on salinity and spawning. Russel Dize, a fourth generation waterman from Tilghman Island, believes that the Bay is healthier than it’s been in a long time:

“Don’t get me wrong. It could be better, but if we didn’t have [the oyster disease] MSX we’d be up to our tailbones in oysters.” Dize is founder of the Maryland Watermen’s Association, a lobbying group for those who make their living on the water.

Blackistone’s book validates the knowledge and commitment of Dize, Fithian and many others: “Watermen know best when species are declining, improving, or thriving. … They know them because their existence depends on that knowledge.”

Much of Blackistone’s text is documentary, as he takes us through a year’s worth of fishing, a year’s worth of celebrating — his first chapter is called “Festivals on the Bay” — and provides a catalogue of Bay-related legislation. But the telling of his days with the watermen is purely conversational, including both the humor and drudgery involved in a very physical occupation. Candid black and white photographs put faces to the names of his subjects and their craft.

Whether hand-tonging for oysters with ‘Jimbo’ Emmert on the South River or standing knee deep in mud shad with Walter Irving Maddox Sr. on the Potomac, Blackistone is at home on the water. His ancestors settled on the lower Potomac in 1634 and have been there ever since; he now lives in Fairhaven. He is vice president of government relations for the National Marine Manufacturers Association and has been appointed by three U.S. presidents to serve as a member of the National Boating Safety Advisory Council.

Dancing with the Tides is Blackistone’s seventh book. As well as Sunup to Sundown, his books for adults include Just Passing Through, a book of poetry. For children, he’s written The Day They Left the Bay, The Buffalo and the River and Broken Wings Will Fly, all with environmental themes.