Sneaking Up on Clear Water: Bernie Wades Again

Sneaking Up on Clear Water: Bernie Wades Again

On the second Sunday in June at Broomes Island, Sen. Bernie Fowler and company once again held hands and walked, white sneakers and all, into the Patuxent River. The former state senator and Patuxent River enthusiast started the tradition in 1988 by putting on overalls and sneakers and wading into the same river where he could, as a young man, go chest-deep and still see his feet.

On the 15th annual Wade-In to measure water clarity, shoes disappeared at about 42.75 inches. Getting wet alongside Fowler this year were some 75 people. It’s an election year, so the company included its share of politicians, headed by Congressman Steny Hoyer and Maryland Senate President Mike Miller.

Arm in arm were people for whom the Wade-In has become an annual ritual. The Wade-In is a reunion for Betty Brady, a former environmental education teacher at Hollywood Elementary School in St. Mary’s County, who now lives in Georgia. She comes back every year on the second Sunday in June to catch up with old friends.

“A lot of people bring picnic baskets and some bring guitars and we just have sort of a big country picnic,” Fowler said.

Fowler’s Wade-In has caught on throughout Chesapeake Country. Mayor Ellen Moyer and two dozen fellow Annapolitans watched from shore Saturday morning as environmentalist Steve Carr and Del. Dick D’Amato waded alone up to their navels in Eastport’s Back Creek. Carr said he could see D’Amato’s shoes beneath 44 inches of water — up seven inches from last year — but D’Amato wasn’t convinced.

“I’m not cheating,” Carr insisted. “I can see your shoes.”

“We don’t have an appeals process,” Moyer said from shore.

Waders also measured the clarity of College, Weems and Spa creeks in Annapolis.

At the Calvert-Anne Arundel line, some 30 people waded into Herring Bay at Rose Haven, losing sight of their toes at a half inch more than three feet.

“Everyone, especially the people more knowledgable about the Bay, was amazed at the clarity of the water,” said Dotty Chaney, partner in Herrington Harbour Resort Marina and candidate for the Maryland General Assembly in District 33B.

Further proof that the water of Herring Bay is getting cleaner comes in the reappearance of diamondback terrapins in the wetlands of Herrington Harbour, one of only four nesting sites in Maryland.

|

|

Retired state Senator Bernie Fowler wades into the Patuxent River with a group of friends and supporters, after which Congressman Steny Hoyer measures how high up on Fowler’s overalls get wet.

photos courtesy of US EPA Bay Program

|

One of the reasons terrapins are scarce is that hatchlings, about the size of a quarter, make a desirable snack for blue herons. To save the turtles, the landscaping maintance group of Herrington Harbour captures the hatchlings. Employee Tracy Harris raises them in a tank for roughly a year until they are about five to six times bigger, or at least too big for snacks.

Wade-In day, eight terrapins were returned to the marsh with the help of a few eager children. Four turtles at a time were placed in a circle drawn in the sand and surrounded by a group of children. Whatever child a young amphibian reached had the pleasure of personally releasing the turtle into the marsh.

“The children just love it, and it’s a very good hands-on educational tool for them,” said Dotty Chaney.

Bernie Fowler’s Wade-In also inspired a corresponding Dip-In in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. Since the Baltimore waters did not have an ideal spot for waders, an eight to nine-inch Secchi disk was lowered in to measure water clarity. It wasn’t as much fun as wading in, but people got on the Bay in boats to do the testing themselves and, while they were at it, get a firsthand look at problems and projects to improve the water quality of the Baltimore Harbor.

— Katie McLaughlin and Brent Seabrook

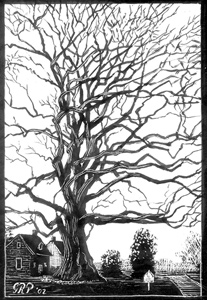

Appreciation: The Wye Oak

Appreciation: The Wye Oak

The felling of the Wye Oak last week gave us another lesson in loss. The 60-mph wind that slammed into the 460-year-old white oak tree reminded us that even our most powerful and important symbols won’t last forever.

The loss seems even more poignant, coming so soon after September 11 and then, closer to home, the F4 tornado that did so much damage in April.

The loss also reminds us that symbols are important. Many Marylanders who never visited the Wye Oak still felt the loss, perhaps because the Wye Oak lived in their imaginations. Symbolic places — whether the Wye Oak State Park or the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge — are places we can mentally visit to experience peace or wildness, beauty or inspiration.

The Wye Oak symbolized strength and endurance. It was also a living reminder that the land was here before the people. Just as the tree itself pre-dated colonial settlement, the land where the tree grew, as well as all the species of animals and plants that are native to this place have existed here for eons. Now, a living link to our distant past is gone.

— Gary Pendleton

|

Sue Wilkinson-Megaw, of Fairfax, is welcomed to the Maryland shore of the Potomac after four hours 44 minutes and 33 seconds of swimming.

photos by Curtis Dalpra

|

All Wet for the Bay’s Sake

People will go to great lengths to show affection and increase awareness for the Bay and its tributaries.

Bernie Fowler and friends got more than their socks wet wading navel-deep into the Bay to measure the clarity of the water by how far away they could walk before their shoes faded from sight, but on June 1, 31 people got all wet for the Bay’s sake. Swimming over 7.5 miles from Hull Neck, Virginia, the fastest swimmer stepped ashore in two hours 42 minutes and 46 seconds. Sixteen-year-old Guillermo Garcia set that record on his first Potomac River swim.

The slowest swimmer stayed in the water for close to seven hours. That’s real love for our waters.

The ninth annual Potomac Swim for the Environment, a challenge of endurance for distance swimmers, broke several records this year, more than doubling the number of swimmers. As well as a new best time, a record $11,500 was raised by the contestants to support environmental efforts for the river. Last year’s swimmers raised $7,000. Dozens of volunteer kayakers as well as members of the Coast Guard paddled alongside swimmers for safety.

Joe Stewart, the man behind the swim, returned to the water this year. “It was a lot of fun just being a participant,” he said, “It’s a different experience to be a swimmer in the water instead of the organizer.”

— Katie McLaughlin

The Coast Guard Wants You

The Coast Guard Wants You

Ever thought about going out on a boat and rafting up with 33,000 of your closest friends? You could watch the sun sink over the water, maybe do a few seamanship drills. How about if you could save a life or two in the process?

The Coast Guard Auxiliary might be for you.

The Coast Guard Auxiliary, all 33,000 of them spread throughout the nation, are civilians who volunteer their time, and sometimes their boats, to help the U.S. Coast Guard keep the waterways safe. Auxiliarists, as they’re called, patrol the inland waterways. They conduct courtesy boat examinations. They teach safe boating courses to the public. They go out on search-and-rescue operations sometimes. And, since September 11, they have been doing more and more to support the Coast Guard — like serving as radio watchstanders at Coast Guard stations — so that the regular Coast Guard is free to maintain the stepped-up patrols and other duties that have come with this post-terrorist world.

The Coast Guard Auxiliary, founded in 1939, is flourishing around the Chesapeake Bay. And no wonder: the Auxiliary was first formed in response to the soaring popularity of recreational boating during the 1930s. With so many casual boaters plying the inland waterways, including the lakes created by Depression-era dam construction, the Coast Guard’s traditional mission of rescuing trouble-stricken mariners was getting a whole lot harder.

So Congress authorized the civilian auxiliary (then called the Coast Guard Reserve) to help with the job. That mission has broadened over the years, and since passage of the Coast Guard Authorization Act of 1996, Auxiliarists may assist the Coast Guard with any Coast Guard function, duty, role, mission or operation authorized by law. Here, in the land of pleasant boating, there’s plenty for an Auxiliarist to do.

The Auxiliary has racked up an impressive list of accomplishments since 1939. To run the numbers: In the year 2000, Auxiliarists saved 311 lives, assisted 10,204 individuals, performed 108,981 vessel inspections, visited 36,740 marine dealers and taught 4,088 public boating classes.

Or to break the numbers down another way: A day in the life of the Coast Guard Auxiliary in the year 2000 was a busy one, with an average of six regatta patrols, 10 search-and-rescue assists, 288 vessel inspections, 62 safety patrols and 219 public affairs, operational or administrative missions. On that same average day, the Auxiliary also saved $341,290 worth of property, educated 369 people in recreational boating safety and marine environmental protection and saved the life of one recreational boater — someone whose death would have otherwise been certain — in U.S. waterways.

If you prefer not to crunch numbers, try looking at it another way: Bay Country is afloat with a wealth of local Auxiliary flotillas, all of them open to applications for new members. And despite the flotilla name for the basic Auxiliary unit, members don’t need to own “facilities” (a boat, plane or radio station) to join and take part in the four cornerstones of the Auxiliary mission: vessel examination, public education, operations (such as patrols) and fellowship.

Learn more about the Coast Guard Auxiliary at West Annapolis Flotilla 15-01’s Appreciation Day at the Annapolis Coast Guard Station at Thomas Point on Saturday, June 15, from 9am to 5pm: 410/267-8108 • www.cgaux.org.

— April Falcon Doss

New Chapter to Old Story at City Dock

New Chapter to Old Story at City Dock

For 10 years, Leonard Blackshear struggled to do what some thought could never be done: Erect a memorial to an African American slave in the capital of a southern state.

Clearly, Blackshear — and all who worked with him and before him — prevailed. Over two and a half years, Alex Haley has become a familiar presence at Annapolis City Dock, 45 miles south of the Mason-Dixon line. Brown-baggers sit with him to eat lunch; tourists pose for pictures at his side. With his trio of listening kids, Alex is such a friendly presence that it’s easy to forget that he sits in our midst to memorialize the spot where his forefather Kunta Kinte was sold into slavery.

Now it will be easier to remember. On June 12, the final elements of the Kunta Kinte-Alex Haley Memorial — a wall of plaques quoting Haley’s Roots and a compass rose pointing back to Atlantic shores — were dedicated in downtown Annapolis. The wall’s dedication reads, “to those nameless Africans, brought to the New World against their will, who struggled against terrible odds to maintain family, culture, identity, and above all, hope.”

Blackshear defines the expansive memorial as more than a success for African Americans. He calls it “a place to go to begin the process to find reconciliation and closure, to begin to move away from the anger, the hatred and the guilt” that are slavery’s legacy.

“The memorial isn’t just about slavery,” Blackshear said, “but about the values that helped African Americans survive slavery. Those values are universal. They help us get through life.”

“The memorial isn’t just about slavery,” Blackshear said, “but about the values that helped African Americans survive slavery. Those values are universal. They help us get through life.”

Blackshear need not have noted how universal those values are. The ceremony was attended by hundreds, a mosaic of people from a multitude of backgrounds and walks of life. Gov. Parris Glendening, Mayor Ellen Moyer and assorted public officials joined members of the Haley family and actors for the television version of Roots.

The success of this endeavor doesn’t mean Blackshear’s task has ended.

“This is the end of the beginning,” he said.

Finally, he sees a start on bringing the memorial into people’s hearts as well as their capital. He envisions school programs to teach children about the values symbolized by the memorial and embodied in the struggle of African Americans. That’s a monumental task, likely to last the rest of Blackshear’s days.

— Brent Seabrook

Way Downstream …

In Baltimore, Mayor Martin O’Malley was none too happy about being forced by the EPA to fix the city’s polluting sewer system. “Unfortunately, our federal government is a lot better at sending lawyers to cities than they are in sending dollars,” he said …

In Chesapeake Bay, a bi-state panel that oversees fishing on the Potomac River has irritated Maryland watermen by imposing a new five-and-one-fourth-inch minimum size limit on sooks, or mature female crabs, from September 1 until the close of crabbing season. While there’s such a limit on males, neither state has a limit on females. Marylanders argued that culling would be too time-consuming during heavy catches of females in the fall …

In Minnesota, Gov. Jesse Ventura must be looking for Huck Finn. The pro-wrestler turned politician and two buddies plan to zoom the entire length of the Mississippi River this summer on jet skis. The salty guv said he intended to buy a new one for the trip. “Then I’ll have five of the damn things,” he said …

Our Creature Feature comes from the British seaside retreat of Weymouth, where swimmers are being advised to steer clear of a sexually frustrated dolphin. The 400-pound fellow, named Georges, has been attempting to lure women from the shallow waters with cute tricks before accosting them with mating-like moves.

He also has been rubbing against boat propellers, nicking himself several times in the process. Authorities say he has become quite the tourist attraction, but they’re attempting to capture him and transport him far away before someone gets seriously hurt, probably Georges himself.