|

by Vivian I. Zumstein

It’s been a tough year for the brightest bird on the block.

But for once, it’s not our fault.

As she opens the nest box, Arlene Ripley heaves a heavy sigh. “A tragedy,” mutters the coordinator of the Calvert Bluebird Council, as she pulls out a soggy nest and lays it on the muddy earth. The nest explodes with ants. They have invaded the box in an unsuccessful search for a drier home during the endless days of rain.

Amid the scurrying ants and sodden woven grass rest the remains of three young Eastern bluebirds. Ripley uses her trowel to stretch out the wing of one of the lifeless creatures, revealing brilliant blue feathers. “This one was a male.” She shakes her head. “Very sad.”

Ripley, who has invested countless hours in bluebirds, checks the data from her previous visit. “This nest had four young. Maybe at least one of them fledged,” she says, her frustration evident as she shovels some dirt over the nest and birds, creating a makeshift grave.

Far fewer Eastern bluebirds are nesting in bluebird-rich Calvert and Anne Arundel counties this year than last. Nor is this decline restricted to Chesapeake Country. This spring Ripley’s colleagues throughout eastern Maryland and as far away as Pennsylvania all report a drastic drop in bluebirds, both in sightings of the birds themselves and in evidence of nesting. No formal studies have been done, but Ripley blames this year’s heavy winter snows and the cool, wet spring.

Bluebird lovers and more casual bird watchers lament the bluebird’s decline. The bluebird’s bright blue and red colors set it apart from other birds. Only the male goldfinch decked out in its dazzling yellow mating plumage or the flashy red male cardinal can compete with the flamboyance of a male bluebird. Other routine garden visitors pale by comparison.

In a Squeeze In a Squeeze

Chesapeake Country’s bluebird — one of three types of bluebirds — is a success story, albeit a modest one. Legions of volunteers contributed to today’s relative abundance of the attractive little bird.

Once a common bird flitting about the countryside, the bluebird began to disappear as early as the mid-1800s. The culprit? Humans were, and remain, bluebirds’ biggest enemy — and also their greatest friend.

Surprisingly, the arrival of farmers benefited the bird. Settlers cleared large tracts of forests to farm, creating the ideal environment for bluebirds: open fields near woods with many tree holes for nests. Even fence posts surrounding fields aided the bird. Made of thick branches or sapling trunks, they promised good nesting.

But times change. Metal posts replaced wooden ones and progress gobbled up open spaces. As cities and towns expanded, farms and woods vanished under the tracks of bulldozers. Unable to adjust to urban or suburban settings, the bluebird fled or died out.

All this time, another kind of European immigrant was causing trouble for native bluebirds. Arriving in the mid-19th century, house sparrows and the starlings laid claim to the tree holes bluebirds favored. “House sparrows are a big problem,” says Ripley. “They are so aggressive they’d just as soon kill a bluebird as look at it.”

Food became scarcer, too, as flocks of starlings stripped bushes of the winter berries on which bluebirds depended.

Heavy pesticide use in the mid-1900s delivered yet another blow by destroying the insects the bird eats. Bluebird populations dropped as much as 90 percent between the mid-1800s and the 1970s.

Housing Shortage

Eviction is a problem bluebirds still suffer.

Calvert County is particularly blessed with bluebirds, but even here the sudden glint of blue startles the passerby as an adult bird makes a quick escape from a newspaper delivery tube. Inside the young mouths gape as large heads, naked but for a few tufts of fluffy down, weave wildly on spindly necks.

A paper tube does not make a good nest. Proximity to humans virtually guarantees discovery, and the heat inside is intense. A sleepy route carrier could crush the birds by stuffing a newspaper in the tube at three in the morning.

Bluebirds nesting in paper tubes implies too few more suitable places.

Bluebirds have rebounded in Chesapeake Country over the last 30 years in part because volunteers built bluebird trails and hundreds of nest boxes in locations favored by the birds. To discourage house sparrows, volunteers located the trails far from human activity. Small entrance holes prevent larger starlings from getting in.

Despite continued development of open spaces, the numbers of Eastern bluebirds across the United States grew an average of five percent every year between 1976 and 1996, according to a U.S. Geological Survey breeding bird survey.

This season, however, there are few bluebirds to bring happiness to Chesapeake Country.

On the Trail On the Trail

“Have you got bug spray?” Ripley asks. “You’ll need it. The deer flies can be fierce.”

Ripley and I are trekking through the Huntingtown Natural Resource Management Area to monitor 26 bluebird boxes. As we bounce along the rutted, little-used road in Ripley’s sturdy SUV, she explains how depressing this year is. Despite the rare treat of sunshine and blue skies, Ripley’s mood is low, affected no doubt by the sad discovery of the three dead young in the first box and the prospect of other disappointments on the trail.

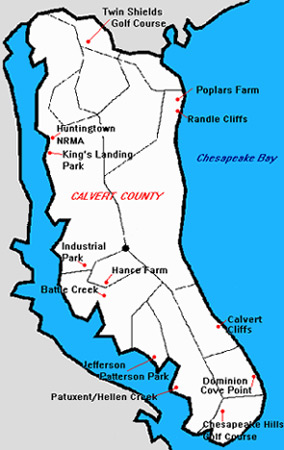

Thirteen bluebird trails are scattered throughout Calvert County, from Twin Shields Golf Course in the north to Chesapeake Hills Golf Course in the south. Anne Arundel County has many trails, too, but they’re not centralized. In addition, countless Chesapeake Country residents have invited bluebirds in with boxes on their properties.

Ideally, bluebird trails meander through pasture land and park lands. Surprisingly, golf courses make inviting habitats for bluebirds. The open, mowed areas mixed with trees and landscaping suit the birds. However, nest boxes at golf courses need to be placed far from buildings, which often attract house sparrows.

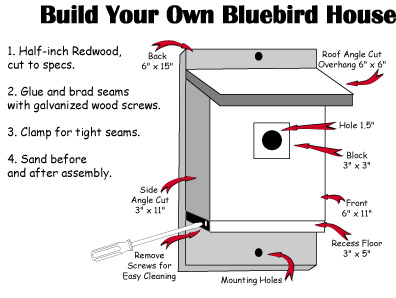

Volunteers install boxes for Eastern bluebirds at least 100 to 150 yards apart on trails. Well-placed boxes have entrance holes facing away from prevailing winds and toward a nearby tree or shrub. Vegetation makes a safe landing for the young when they first leave the nest. The birds favor open areas, but they also need perches, such as a fence line or tree branches, where adults can sit to search for food.

The boxes need protection to keep out predators, especially snakes. Some monitors keep the support poles greased. The boxes along the Huntingtown Natural Resource Management Area trail have large inverted cones mounted below the boxes, preventing predators from reaching the eggs or the young.

The Day’s Tally The Day’s Tally

Traditionally, the Huntingtown Natural Resource Management Area bluebird trail yields many eggs and young. Last year, 41 nests were counted by the end of June. Not today. Box after box sits empty. Some, Ripley doesn’t even bother to open. She sees no nearby adult activity, no telltale wisps of grass suggesting a nest. A bluebird veteran like Ripley doesn’t need to open the box to know it’s vacant.

At many stops, Ripley laments the collateral effects of the heavy rain. “I’ve never seen the grasses this high in June,” she says. “I’ll have to get in here with the weed eater.” The weeds reach nearly as high as the holes to some nest boxes, a condition the birds do not like. As if they didn’t already have enough reasons not to nest.

Finally, as the SUV bounces along the edge of a cornfield skirting the outer row of knee-high plants, an adult bolts from a box. Briefly heartened, Ripley opens it only to find the nest empty. At least it’s a start. Perhaps it will have eggs the next visit.

A few stops later, Ripley pulls up in front of a clearly occupied box. “Watch out for the poison ivy,” she cautions. Suddenly, a huge black vulture bursts from the underbrush a few yards away and launches into the air with powerful wing beats. It happens so fast I don’t even have time to be startled. “That vulture has nested in that same spot for the last few years,” Ripley remarks without batting an eyelash.

Apparently, bluebirds favor this site, too. Inside the box sits a delicately woven nest of grasses. “I think we’ll get lucky this time,” predicts Ripley as she holds a small mirror up inside the box. Sure enough, the reflection reveals five small, slightly bluish eggs cradled in the nest. Pay dirt! This is what Ripley and all bluebird trail monitors want to see. Unfortunately, we record few eggs this visit.

Plenty of other wildlife crosses our path during 90 minutes in the field. Startled deer bound ahead, crossing the cornfields in huge leaps before scattering into the woods. Ripley, with her eagle eye, stops to allow a five-foot-long black snake to slither to safety across the grass-covered road in front of the SUV. She spots a pair of blue grosbeaks and treats me to a look at them through her binoculars. Tree swallows occupy some of the boxes, swooping above us in graceful arcs as we inspect their nests. On the way to monitor one box, Ripley rescues a small mud turtle stranded on its back. And deer flies. Ripley was right. There are plenty of deer flies, and they are indeed fierce.

Bluebirds, however, remain elusive. Our bluebird tally for the day consists of sighting a handful of adults, five nests, 14 eggs, no young and 15 fledged (young assumed to have left the nest). Added to the three dead birds at the beginning of the trail, it’s a dismal day.

Depressing Numbers

Calvert County and Anne Arundel counties both have robust bluebird programs, and both have found sharp drops in their favorite bird this season. Because Calvert bluebird enthusiasts have centralized their county-wide efforts, they have a more complete story to tell.

Members of the Calvert Bluebird Council check almost 300 nest boxes on 13 trails. These volunteers collect data on nests, eggs, young and fledges, and they frequently provide figures to Ripley, who in turn updates their web site — (www.nestbox.com — for records dating back to 1988.) This regular flow of information proves that bluebird breeding totals in Calvert County are down — way down.

For example, by the end of July 2002, the Calvert Bluebird Council recorded 376 bluebird nests. Monitors counted only 96 nests (26 percent of the July 2002 total) by the end of July 2003.

Trail monitors have also reported finding far more dead young in nests than in years past. Over the last four years, an average of almost 89 percent of young birds survived to leave the nest. Early numbers for the 2003 breeding year show this percentage fell sharply.

In Anne Arundel County, the story is not so clear — but its outline is no happier. There, volunteers check boxes on numerous bluebird trails, but no one consolidates county-wide figures. Some monitors do collect information all spring and summer, but they don’t forward it to a local coordinator until after the breeding season is over in September.

Anne Arundel birdwatchers report that sighting a bluebird this year is rare. Ranger Bob Hicks, who established a trail with 65 nest boxes at Kinder Farm Park, says his volunteers have seen fewer bluebird nests than normal. Other birds are using the boxes.

Doug Forsell, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has been a bluebird volunteer for a decade. He monitors two trails with a total of 65 boxes at the Naval Academy Golf Course and Greenbury Point. By July 4, 2002, he recorded 53 nests. This year yielded a paltry 13. Only 11 young have fledged from his boxes, far less than the 134 that did so over the same period last year.

“I cannot recall a dip in bluebird breeding as large as this,” says Forsell.

What’s to Blame?

Ripley blames the weather. She thinks many birds starved over the harsh winter when heavy snows covered berry-producing plants for weeks and the bluebirds couldn’t reach their food.

Her evidence? On her first visit this spring to the Huntingtown Natural Resource Management Area, she found three dead adult females in a single nest box. “They huddled for warmth and were just too weak to leave,” she says. Other volunteers also report multiple dead adults in boxes this year.

Our cool spring also reduced the numbers of insects the birds eat. What with mosquitoes and other flying insects harassing Chesapeake Country this summer, you may wonder how food could be scarce for the bluebird. There are insects and then there are insects. Bluebirds feed on grasshoppers, crickets, ground beetles and grubs — all bugs that live on or near the ground. The wet conditions that produce bumper crops of many flying insects do not necessarily enhance the environment of the ground-dwelling insects, which may not tolerate consistently damp and muddy earth.

Bluebirds need plenty of high-protein insects in the spring and summer to feed both themselves and their young. “The parents have to get the young out of the nest quickly,” explains Ripley. And not only because the caloric demands of the fast-growing young are so high. “Birds in nests are, well, sitting ducks,” she says, smiling at her pun.

The unusually high number of dead young in boxes this year suggests parents were indeed not able to find enough insects to feed their young.

Fewer insects hit the species with a double whammy. “Fledgling survival is normally low,” Ripley says. “It will be even lower when competing for such a scarce food supply.”

Hard Truths Hard Truths

This year, at least, there’s not much humans can do to help. Lack of nesting sites is not an issue. Empty nest boxes abound. Winter feeding can help — except that bluebirds do not normally explore their surroundings looking for feeders. Even providing mealworms, a good food for the birds, will not automatically entice bluebirds to a feeder.

Some local bluebird lovers sustained a few birds through the worst of the winter snows, but for the most part, these birds were already regular visitors to the feeders. When Ripley saw that winter was taking a terrible toll, she hand-fed birds in her yard.

Six bluebirds showed up at my suet feeder about a week after the first snow. They were first-time visitors, and they came daily until the thaw uncovered their winter supply of holly, dogwood and sumac berries.

I enjoyed seeing the small birds, looking grumpy, all puffed up against the cold. Their bright blue and red contrasted vividly with the white snow. Little did I know that their presence meant they were on the brink of starvation. I only hope the birds in my small flock were among the winter’s survivors.

Bird-friendly landscaping with more berry-producing plants helps bluebirds during most winters. But if snow covers the plants for days on end, it doesn’t matter how many berries there are.

Dismal Forecast

Bluebirders don’t think like you and me. They were praying warmer summer weather would mean more insects to help the birds rebound.

Their prayers were not answered. Perhaps insects increased, but bluebird nests did not. Despite the warmer late-summer temperatures, the persistent wet conditions continue to keep insects below normal levels. Apparently, bluebirds recognize the shortfall and skip nesting lest they hatch chicks they won’t be able to feed.

In good breeding seasons, bluebird pairs can raise two sets of young. Very successful pairs may even raise three. But this July, bluebirds built few new nests. Only a handful of birds will raise second families this year.

The lack of a nesting rebound tells Ripley that far more adults perished during the winter than she at first believed. This year’s poor breeding season seems to confirm her fear that there are too few adults.

So Arlene Ripley continues to have a blue summer. For a dedicated bluebirder, there’s not much to smile about. “I expect next year to be bad, too,” she says.

About the Author:

Vivian Zumstein is a retired Navy commander and the mother of four. Haling from the Puget Sound area of Washington State, she has lived for 12 years in Calvert County, where she coaches soccer, volunteers in the local schools and communes with nature. |

|

Calvert Bluebird Council Data for 2001–2003

Data for each month reflect cumulative totals.

April May June July April May June July

Nests 2001

165 214 353 418

Nests 2002

172 232 354 376

Nests 2003

13 59 84 96

Eggs 2001

441 809 1,328 1,556

Eggs 2002

499 820 1, 203 1,393

Eggs 2003

27 182 279 316

Young 2001

27 552 716 1,040

Young 2002

77 513 707 885

Young 2003

3 103 160 215

Fledges 2001

0 303 552 829

Fledges 2002

0 203 452 642

Fledges 2003

0 27 87 122

to the top

|

|