|

|

Oyster Times

Walk with Us Through the Decline of Chesapeake Bay’s Native Oyster and the Rise of Its Alien Cousin

Times of Virginica

Our native oysters are in a world of trouble. The byproducts of our habitation of Chesapeake Country have made the Bay a tough place for oysters to live. At the same time, our appetite for oysters has outgobbled the resource. Now few and weak, the Bay’s remaining oysters are dying of infection by the microscopic oyster predators dermo and MSX.

|

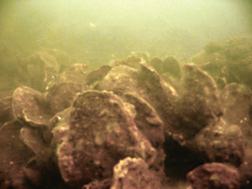

photo courtesy of PaynterLab of University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science

A restored reef of native Chesapeake oysters. |

In finding ways to keep Crassostrea virginica alive, we’ve pushed the limits of human ingenuity. Scientists and entrepreneurs have tried hundreds of variations on seed, seed-planting and reef building. Even turning Baltimore’s hallowed Memorial Stadium into oyster reefs hasn’t turned the tide.

For perspective, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation scores the Bay’s health on a scale of 100 each year, measuring against the pristine standards recorded by Captain John Smith on his explorations of some 400 years ago. Since the first year of scoring in 1998 the oyster fishery has suffered a stagnant score of two.

1885-’90

Maryland’s oyster harvest peaks at 15 million bushels. Some 32,000 Marylanders earn their livings in the oyster industry. The conservation-minded cull law — setting a size limit on catches — is passed.

1974-1975

2,559,112 bushels of native oysters harvested from Chesapeake Bay.

1982-1983

Disease delivers a shock, dropping harvests to 1,481,942 bushels, a 28-percent decline from the previous season.

1985-1986

The last season to top one million bushels, with 1,557,091 harvested. Two thousand to 3,000 oystermen still work the waters.

1993-1994

The oyster harvest hits a record low: 70,618 bushels.

2002–’03

Chesapeake Bay’s oyster harvest bottoms out with 53,000 bushels. The disastrous season sees record high infections and, between dermo and MSX, a range of infection between 88 and 94 percent of Bay oyster sites.

2003-’04

Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ Shellfish Division projects this season’s harvest at a mere 15,000 bushels … Only 279 oystermen are active, down from 437 last season and 1,293 in 2001 … Over the past decade, oyster processing plants have diminished from 30 to three.

“The future for at least four years out is very bleak,” says DNR shellfish expert Chris Judy. Drought from 1999 to 2002 incubated disease with warmer, saltier waters. The rains of 2003, though fortuitous for some sites, were not enough to turn the tide. Much more rain is needed if new spat sets — the industry’s hope for recovery — are to thrive.

University of Maryland’s Horn Point hatchery aims to counter failing natural production, with farm-raised spat dispersed to corners of the Bay with low disease pressure. Recently established sanctuaries give new oysters the time and space to grow.

More hope comes from new disease-resistant native oyster strains, DEBY and CROSBreed, bred under supervision of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Successes in Virginia tributaries have spurred the Army Corps of Engineers to plan spreading millions more of the disease-resistant DEBY strain oysters throughout the Chesapeake with hopes of reestablishing self-sustaining reefs. Most will probably die of disease, but survivors may anchor revival.

- O Oysters, come and walk with us!

The Walrus did beseech.

A pleasant walk, a pleasant talk,

Along the briny beach.

—f rom Lewis Carroll’s poem “The Walrus and the Carpenter”

in Through the Looking-Glass

Longer than memory has America’s eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, flourished in Chesapeake Bay. Asian cousin Crassostrea ariakensis is a newcomer that’s barely touched these waters. In less time than we’ve known ariakensis’ name, that balance could reverse.

Virginia and Maryland, the Bay’s oyster states, are nowadays sounding a lot like Lewis Carroll’s walrus in wooing ariakensis.

Will we will be lured (and devoured) like the young oysters in Carroll’s poem if we pin our hopes for restoring oysters and oystering in Chesapeake Bay on a foreign oyster, Crassostrea ariakensis, the Suminoe or Asian oyster?

|

photo courtesy Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Ariakensis oysters, at top, outgrew natives, at bottom, in Virginia trials. |

Only time will tell.

So as the plot thickens like a rich oyster stew, we bring you the Bay times of those oyster cousins.

The Thickening Plot

Debate over Crassostrea ariakensis seesaws pro and con. In this century, Virginia scientists at the Marine Resources Commission and boosters at the Seafood Council, as well as some Maryland and Virginia watermen, have supported Asian oysters as the most promising solution for revitalizing the industry. Ariakensis grows more than twice as fast as the native Chesapeake Bay oyster, and it is resistant to dermo and MSX, diseases that have ravaged native oysters.

Now ariakensis also has powerful Maryland friends, with Gov. Robert Ehrlich on its side and the state’s Department of Natural Resources stirring the pot.

But other scientists and environmentalists remain skeptical about how non-native oysters might behave in the wild, worrying that the alien species could overtake Bay and coastal waters. Topping that worry is concern about what will become of the years of effort and the millions of dollars spent to restore native oyster reefs in the Chesapeake Bay.

The middle road, espoused by the National Academy of Science, has been to keep those aliens caged until they’ve been better studied. But year by year, native harvests drop and pressure builds to reoyster Chesapeake Bay by any means possible.

Ariakensis Prehistory

Ariakensis is a wide-ranging native species in the Far East, where it has also been aquacultured. The oyster originally inhabited the Ariake Bay in Japan, from which it takes its name. But the species died off there between 1925 and 1940, a mass mortality attributed to a rapid rise of water temperature and salinity.

In Chesapeake Bay, temperature and salinity both run the gamut. Salinities range from ocean-salty — 28 parts per million at the mouth of the Bay in Virginia — to nearly fresh up high in the Bay and its tributaries. Keep salinity in mind, because it turns up again in full-salt — 30 parts per million — coastal waters.

Another Asian oyster, Crassostrea gigas was introduced in the Bay back in the 1960s. Gigas is the oyster that repopulated the Pacific Northwest coast, but it did not thrive in low-salinity Chesapeake beds.

1990

Virginia’s Marine Resources Commission first considers introducing another Asian oyster, ariakensis, to the Bay. At the time, Virginia Institute of Marine Science professor Roger Mann said “the worst-case scenario is that these animals will spawn, spread up and down the Bay and displace the native oysters. We are up against the wall here. But we are in the situation of potentially having to take a risk here.”

Alien oysters on trial throughout our region are produced at Virginia Institute of Marine Science to be aquacultured in trays or mesh bags, not seeded in free-water oyster beds. They’re also genetically engineered to be non-reproducing.

1995

The Virginia Legislature directs the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to begin a study of non-native oyster species for possible introduction to the Chesapeake Bay. First studies confirm that gigas is not the species for Chesapeake Bay.

1996

Seeking another candidate, researchers at Virginia Institute of Marine Science begin to produce sterile ariakensis for controlled studies.

In the short term, ariakensis is considered as an annual crop to be farmed and harvested in plots of Chesapeake waters. In the long term, it’s talked of as partner, if not a successor, to virginica.

1999

Virginia Institute of Marine Science releases data showing that gigas has poor commercial potential. But ariakensis shows promise, and Virginia Marine Resources Commission — the equivalent of the fisheries branch of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources — approves the Institute’s marketability proposal for this oyster.

2000 ~ Steps toward testing Ariakensis

Chesapeake Bay Program approves Virginia Institute of Marine Science’s marketability proposal to test ariakensis.

|

photo courtesy of University of Maryland Center for Estuarine Studeis

Mountains of cleaned oyster shells at the Horn Point facility await seeding and replanting. |

Virginia Seafood Council asks permission to test 6,000 ariakensis deployed in floating cages at six open-water sites.

Virginia Marine Resources Commission approves Virginia Seafood Council request for in-water tests.

Limited tests begin; Virginia aquaculturists grow sterile ariakensis seed oysters in Virginia waters.

Chesapeake 2000 Agreement commits to increasing native oysters tenfold by 2010

The watershed partnership of the states — Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, the District of Columbia, the Chesapeake Bay Commission and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — signed historic agreements in 1983 and 1987, establishing the Chesapeake Bay Program partnership to protect and restore the Chesapeake Bay’s ecosystem.

Now, they reaffirm their partnership, committing to achieve by 2010 a tenfold increase in native oysters in the Chesapeake Bay, based upon a 1994 baseline. By 2002, they agree to develop and implement a strategy to achieve this increase by using sanctuaries, aquaculture, continued research into oyster diseases and developing disease-resistant oysters — plus “other management approaches.”

2001 ~ Score a big one for Ariakensis

Asian test oysters in Virginia rivers grow to market size nearly twice as fast as native oysters, thrilling Virginia watermen and fueling debate among state and federal agencies over introducing the foreign species to Bay.

“In nine months,” said Jim Wesson, who directs oyster restoration for the Virginia Marine Resources Commission, “every one of the ariakensis had reached market size with no mortality, while the virginica that survived — and a great many were dead — are still not at market size.”

Lose two for Ariakensis

Maryland Department of Natural Resources advises against introduction fearing “unforeseen consequences.”

No matter how impressive the results, Chesapeake Bay Foundation says there can be more to ariakensis than meets the eye. Advising caution in a December Position Paper, the Foundation calls for “substantial scientifically validated information about the ecological risks and benefits.” Also seeks “independent review by the National Academy of Sciences.”

Stay the native oyster course

In December, the Federal Agencies Committee of the Chesapeake Bay Program asks the Bay Partners to “stay the course with the oyster strategy to which we committed in the Chesapeake 2000 Agreement.” The Committee asks the partners to oppose introducing ariakensis “unless environmental and economic evaluations” show low risk. The fear is that introduction may worsen disease problems and detract from funds and efforts of the Chesapeake 2000 commitment to a tenfold increase in native oysters.

2002, January

Encouraged by big, fat, healthy oysters after testing 6,000 ariakensis at six sites, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission approves the Virginia Seafood Council’s request for continued testing. In an upsized trial, 60,000 neutered oysters are planted at 13 sites from the James River, up the Potomac on the Western Shore and up to Pocomoke Sound on the Eastern Shore. These oysters will have to pass the more difficult real-world test of growing on Bay bottoms rather than in floating cages. The council’s members, seafood packers and processors, offer to pay for the experiment.

Help! National Academy of Sciences called in

The Chesapeake Bay Commission calls on the independent academy of the nation’s top scientists to convene an expert panel to consider ariakensis and set future guidelines.

2002, March

The Virginia General Assembly votes to establish a commercial aquaculture industry for the production of genetically sterile crassostrea ariakensis.

But the Assembly also votes to keep ariakensis out of the Bay — for now.

At the same time, Virginia gives scientists three years to find fault with the fast-growing, disease-resistant Asian.

“If such research fails to prove, within three years, that the Crassostrea ariakensis will be harmful,” House Joint Resolution 164 concluded, “the General Assembly suggests the introduction of the reproductive disease-resistant Crassostrea ariakensis into the public waters of the Commonwealth.”

National Academy of Sciences agrees to review the ariakensis issue.

2002, April

The Maryland General Assembly approves research on ariakensis

2002, July

Federal agencies — including NOAA, EPA and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — and state agencies from Maryland and Virginia announce a project to examine the ecological and socio-economic risks and benefits of open-water aquaculture. In other words, they’re looking at direct introduction of ariakensis into Chesapeake Bay.

Virginia’s director of oyster restoration for the Virginia Marine Resource Commission says “the Suminoe oyster offers the best chance for oyster populations in the bay to rebuild.”

Rob Brumbaugh, Chesapeake Bay Foundation fisheries expert says, “anyone who thinks these Asian oysters are going to be some type of silver bullet is going to be sorely disappointed. We’re just not at the point where we should give up on our native oyster.”

2002, November

The partners of the Chesapeake Bay Program follow through on the Chesapeake 2000 Agreement committing to increasing native oysters tenfold by 2010. They release their Draft Chesapeake Bay Comprehensive Oyster Management Plan for rebuilding native oyster populations and improving oyster management. Its steps are managing around disease; establishing sanctuaries; coordinating among oyster partners; and developing a database to track oyster restoration projects.

|

photo courtesy of Virginia Institute of Marine Science

Until doubts are alayed, all Ariekensis experiments are kept in floating cages to keep the aliens from comingling with natives. |

2002, December

Virginia Seafood Commission proposes a privately funded trial to cultivate one million ariakensis in 10 locations to determine their economic potential.

Meanwhile, North Carolina considers using Asian oysters to recoup its own loss of native oysters, planning a two-year test of a half-million genetically sterilized oysters, both Pacific (bred from the Japanese gigas oyster) and ariakensis.

2003, January to February

Virginia Marine Resources Commission approves the Seafood Commission’s privately funded trial of one million ariakensis.

“With the numbers used [in previous research], they didn’t have enough to sell them,” says Virginia Marine Resources Commission’s Wesson.

Approval now rests with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (see April) — though the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also hopes to stop the trial.

Not so fast!

But Chesapeake Bay Program halts the trial until National Academy of Sciences recommendations are published and incorporated into the trial (see August).

2003, April to May

Army Corps of Engineers requires “more stringent conditions” on Virginia’s planned introduction of one million ariakensis oysters. The big worry is the possibility that the alien species might bolt and reproduce in the Bay.

Agreeing to wait for National Academy of Sciences study, the Virginia Seafood Council postpones its request for a state permit to dump one million non-native oysters in Virginia waters.

Virginia processors accuse Maryland of sabotaging the project with federal agencies.

2003, June

“Something needs to be done, and it needs to be done now.”

Gov. Robert Ehrlich takes an “aggressive step,” by pushing the Army Corps of Engineers to make an environmental assessment of seeding the Chesapeake Bay with Asian oysters … announces his administration will pursue the feasibility of introducing the Asian oyster into the Bay.

Ariakensis wins funding in Maryland

NOAA National Sea Grant Program commits funding for two ariakensis studies by the University of Maryland “to help bolster native Eastern oysters, which have been ravaged by disease.” The two-year study will expose non-native species to predators commonly found on Chesapeake Bay oyster bars. But the aliens will be quarantined in a controlled lab setting.

2003, July

Rebounding from rejection earlier in the year, Virginia Seafood Council submits a substantial revision of its one million-oyster test

Chesapeake Bay Foundation endorses the revised proposal by the Virginia Seafood Council to plant one million sterile Asian oysters in Bay and coastal waters.

“We think there may be a real commercial potential for growing sterile oysters in an aquaculture situation,” says Charles Epes, of the Foundation’s turnabout.

“We had some concerns last year, being sure that proper safeguards were in place to ensure that there’s no chance of inadvertent introduction of fertile oysters. Now controls are put in place to as much as humanly possible avoid reproducing non-native oysters in the Bay.”

The one million are “triploid” oysters, which are bred by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to contain three chromosomes, thus rendering the bivalves sterile. They are also tested to prove that they’re disease free.

2003, August ~ Slow and steady

After a year of study, the National Academy of Science’s National Research Council releases its report, recommending a cautious go-slow approach to introduction of non-native Asian oysters. Foreign oysters are not a quick fix for Chesapeake Bay, they conclude, urging at least five years additional research before allowing breeding aliens into the Bay. What’s more, the Academy reports “surprise” that no federal regulatory approval is required, leaving new species introductions up to the states. Still, the Academy says that aquaculture of sterile oysters may help our ailing oyster industry.

The Chesapeake Bay Program watershed partners praise the study, sharing concern over possible “rogue introduction of the Suminoe oyster.”

Trouble brews in North Carolina

Much of the first batch of ariakensis die in the North Carolina test. Fearing a disease, researchers destroy the rest.

2003, September

Virginia floats nearly one million sterile ariakensis. The trial will last through 2005, with regular sampling. A parallel trial also runs with a sterile, disease-tolerant strain of our native oyster virginica to compare its performance to that of ariakensis.

2003, October

Maryland Board of Public Works — including Gov. Ehrlich and Comptroller William Donald Schaefer — gives the go ahead to plant 3,000 caged sterile ariakensis (along with an equal number of native oysters) in Severn River as well as the Choptank and Patuxent. Anne Arundel County environmental officials worry about what unforeseen troubles ariakensis at Severn might lead to.

Army Corps of Engineers must approve trial (see February, 2004).

2003, November

One million dollars for one million ariakensis

Nearly one million federal dollars are promised to support Virginia’s one-million ariakensis test with cosponsoring Virginia Seafood Council. NOAA’s Chesapeake Bay Fisheries Research Program makes the award to Virginia’s Center for Innovative Technology.

2003, December

Ariakensis shows its Achilles heel

A parasite protozoan of a genus previously unknown in the region, Bonamia, is found in ariakensis that died in North Carolina.

Unanticipated problems like this are why testing is so important. Whether Bay ariakensis will be vulnerable remains to be seen. Salinity in North Carolina’s Bogue Sound is 30 parts per million; Chesapeake Bay salinity ranges from 28 at its mouth to less than 10 in many oyster-growing regions of Bay.

“This doesn’t seem to be an issue of C. ariakensis introducing an exotic disease to the native oyster, it’s an issue of a local parasite causing problems in C. ariakensis,” says Eugene Burreson, the Virginia Institute of Marine Science researcher who identified it.

$1 million is dedicated by Maryland for research on fast-growing ariakensis as Maryland’s DNR plans to test its own ariakensis stock before year’s end.

2004 , January

High salinity is blamed for loss of ariakensis to parasites off North Carolina coast.

High salinity also made ariakensis vulnerable in its native waters as well as in France. With lower salinity levels, Maryland may have better luck.

The Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences experiments on the newly discovered parasite, Bonamia, to learn if it will thrive in lower-salinity waters like in Chesapeake Bay.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers joins with Maryland and Virginia in a multi-year study to analyze the environmental impact of “Proposed Introduction of the Oyster Species, Crassostrea Ariakensis, Into the Tidal Waters of Maryland and Virginia.”

Public hearings begin on establishing “naturalized, reproducing, and self-sustaining population of this oyster species.” In other words, we’re talking about free-breeding ariakensis in Chesapeake Bay.

Join the debate in Annapolis at 7pm Monday, January 26, at Radisson Hotel, 210 Holiday Court, Annapolis; free: 410/224-3150.

As ariakensis is evaluated, the Corps pledges to continue native oyster restoration efforts throughout Chesapeake Bay.

2004, February

First ariakensis trials in the Maryland Bay.University of Maryland Center will run side-by-side tests of 1,300 virginica and 1,300 ariakensis in cages at three spots: the Severn River at the Naval Academy, the Patuxent River and the Choptank River.

“The project is permitted, but we’re still working on some conditions with the Army Corps of Engineers,” says principal investigator Kennedy Paynter.

“We feel real good about this study, if it’s conducted with all the safeguards, for it will teach us some things we desperately need to know,” says Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Bill Goldsborough.

2005

Gov. Ehrlich’s target for planting breeding ariakensis in Chesapeake Bay.

Endpoint for Virginia’s one-million ariakensis trial.

2010

Year set by Chesapeake Bay Program in 2000 for increasing tenfold the native oyster populations in Chesapeake Bay from its 1994 base.

— written and compiled by Sandra Martin, M.L. Faunce and Mark Burns

Diseases

Dermo and MSX have together ravaged the Chesapeake’s native oyster population. Both diseases thrive in waters with high salinity and temperatures above 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

Dermo has festered in the Gulf of Mexico since about 1950 and appeared in the Bay as early as 1954. In the late 1980s, the disease hit the Chesapeake in force. Because southern strains of oysters have been subjected to Dermo for so long, these oysters may have developed natural immunities that Bay stocks, which are terribly susceptible, do not have.

MSX (multinucleted sphere x) has proliferated rapidly along the East Coast since 1957, when it was first documented in Delaware Bay. Two years later it invaded the lower Chesapeake; now the parasitic disease ranges from Maine to Florida.

to the top

|

|