Chesapeake Bay's Independent Newspaper ~ Since 1993

1629 Forest Drive, Annapolis, MD 21403 ~ 410-626-9888

Volume xviii, Issue 14 ~ Apri 8 to April 14, 2010

Home \\ Correspondence \\ from the Editor \\ Submit a Letter \\ Classifieds \\ Contact Us

Best of the Bay \\ Dining Guide \\ Home & Garden Guide \\ Archives \\ Distribution \\ Advertising![]()

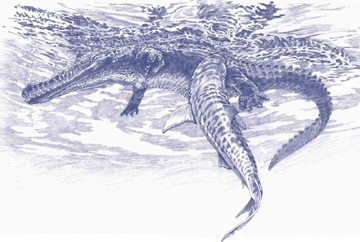

How Did the Crocodile Die?

|

|

|

Drive south to Solomons, and you’ll likely see Douggie Douglass selling his wares on the right side of Route 2/4 near the turn to Calvert Cliffs State Park in Lusby. Signs on his gray pickup read, Sharks Teeth for Sale and Douggie’s Fossils: Specialize in Shark Teeth.

You may not know that the roadside marketer is a footnote in the world of science. Douglass has turned up a full impression of a tiger shark’s bite, preserved about 14 million years ago in a crocodile coprolite — otherwise known as fossilized poo.

The Famous Coprolite

Douglass made his find while going about his ordinary business, searching along Calvert Cliffs. Marvels are nothing new to him, but this day six years ago he knew he’d come upon something special. “I knew it was a tiger shark, and I had found the only one in the world,” he says, perhaps appreciating his discovery in hindsight.

Douglass took the shark-bit fossil to Stephen Godfrey, curator of paleontology at Calvert Marine Museum, who shared his excitement.

“I knew immediately this was very unusual. Coprolites aren’t that rare, but for anyone anywhere to have tooth impressions is exceedingly unlikely. Then to consider, How did this occur? is like a CSI puzzle and begs for an investigation.”

Godfrey did a bit of forensic dentistry, pouring silicone into the zigzag indentation across the coprolite. He pulled out a near-perfect dental set of tiger shark teeth, complete to the little tooth bud in the center of its front teeth. Now Godfrey and his former assistant, Joshua Smith, have published their findings in an international scientific journal, and Douglass’ find has become famous as the first known coprolite to preserve vertebrate tooth marks.

“Douggie knows when something is unusual, when it isn’t the run of the mill,” said Godfrey, himself now another footnote in the vast volumes of paleontology. “I’m delighted that he brings the unusual items to us.”

Godfrey was particularly intrigued because this was a trace fossil, not just teeth and bones, but an artifact made by a living animal.

“I’m more interested in fossils that capture behaviors — feeding behaviors, predatory behaviors, exploratory behaviors — interactions between animals,” Godfrey said. “So these bite marks are a trace fossil in a fossil, and we see defecating behavior and feeding behavior.”

The coprolite is flat, Godfrey explained, because crocodile turds are flat. It’s possible, he says, that the shark may have started to eat the feces, then changed its mind. Perhaps the shark was just checking it out.

Godfrey believes, however, that the estimated 10-foot shark bit into a crocodile’s belly, leaving the deep impressions mostly on just one side of the coprolite with another body part protecting the other side. That portion of the intestine fell to the bottom to harden in the shallow ocean that covered Southern Maryland during the Miocene epoch.

Douglass helped authenticate his find by delivering another fossil broken at the tooth marks.

“When Douggie brought this second fossil to me,” said Godfrey, “I tended to believe him. It’s some neat stuff he finds.”

He Sells Sharks’ Teeth by the Roadside

What about Douglass, the discoverer? Does he do this for a living?

|

|

“I started out here on the road for the children,” Douglass explained. “This is starting my 22nd year. I never thought what it would come to. People yell, Hey, Shark Man.”

Bernie and Glenda Brady pulled up as Douglass and I talked. Bernie displayed a four-inch-long dark, tapered stick.

“That’s a stingray barb,” said Douglass, referring to the ray’s tail. “I know it had to come from Flag Pond. They’re dark from there.”

He was right.

The Bradys look at a whale jawbone shaped like a long club, and Douglass shows them a dog-shaped coprolite.

“You can see where fish have eaten all over that. I’m going to share it with Stephen,” Douglass said, meaning another consultation with the curator.

He sells the palm-sized Miocene scallop shells at two for $10. He also sells starter fossil sets with a variety of shark and fish fossils to help beginners identify the different teeth and vertebrae.

The Discoverer’s Craft

“You make sure there’s beds of shells and rocks and have a sunny day that’ll light up the shells,” Douglass says of how to start a fossil hunt. He suggests using a glass-bottomed bucket or a piece of pipe with Plexiglas at the end that magnifies in the water. “Generally I look in water two to three feet down. My eye seems to pick up whale and crocodile dung. There’s a knack.”

He says there’s a thrill to “being out there. It’s becoming a sport. Everyone is able to be out there. It’s kind of fun and a safe hobby, and nobody’s hurting the beetles.”

He means tiger beetles, another Calvert creature in the news. The beetles live in the eroding cliffs. They are listed as endangered, keeping homeowners from building revetments along the cliff to prevent erosion.

“I don’t know what I’d do if I ever saw a beetle carry away a shark’s tooth,” says Douglass, an environmentalist.

Another driver honks and waves; Douglass waves back.

Hooked on Fossils

|

|

Douglass’ fascination started at Kenwood Beach in Port Republic when he was seven or eight years old.

“When I was young, an older woman tapped her cane on one boulder among many in the water. I turned it over, and there was a hog jaw under it. I went out later and turned over all the other rocks and found nothing. I think she must have had eyes that could see through anything. She said, ‘I’d be glad if I could just get any one of you kids to take this hobby,’ Douglass recounts. “I learned from her.”

Douglass used to dive for fossils using hoses and regulators, but now, in his mid-50s, he prefers to work with his bucket.

Fossil hunting has become his job. He keeps at it, and he’s developed his own eye. So this notable bite plate isn’t the only wonder he has to his credit.

“I found a 50-foot crocodile south of the power plant in Lusby,” he reports. “It had all its teeth still in the jaw. Each tooth was about four inches long. The cliff had fallen down, and it slid down with it.

“And I found a shovel-tusk to a gomphotheres, an early mastodon. It was four feet long, but I found it in pieces of a foot or two, with enamel on both sides of the ivory. I wouldn’t trade it for nothing,” says Douglass.

Douglass and his truck are a Calvert original and a link to the Bay’s bounty of sharks’ teeth and other fossils waiting to be found.

“I look at all of Calvert Cliff as my home,” the discoverer says.” If I had to do something else, I wouldn’t know what to do.”

© COPYRIGHT 2010 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.