Stops on the Road from Slavery to Freedom

by Sandra Martin

Leonard Blackshear has a dream.

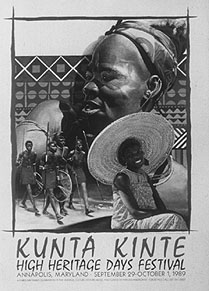

In his dream, Annapolis is the mecca of a pilgrimage of reconciliation, drawing African Americans the way Ellis Island draws European Americans. On the brick sidewalk along Ego Alley, Alex Haley will remind us that other stories have held the stage where Annapolitans and their visitors now gather to strut and see one another's stuff.

Joining three bronze children at the bronze feet of the man whose Roots journey turned America into a nation of genealogists, we'll learn history's

biggest lesson: that ghosts are all around us if we have eyes to see and ears to hear.

For this is the very spot - so Haley believed - where his first ancestor set foot on American soil. Here Kunta Kinte disembarked after a tortuous three-month passage from Gambia to be sold into slavery.

There is no better place than here, Blackshear believes, to begin the story of Africans in America.

"Through Alex Haley's Roots, Kunta Kinte has become

the symbolic African everyman, elevated by his struggle," Blackshear

says. "His point of arrival, Annapolis, becomes in that mythology the

symbolic entry point of the African disapora."

"Through Alex Haley's Roots, Kunta Kinte has become

the symbolic African everyman, elevated by his struggle," Blackshear

says. "His point of arrival, Annapolis, becomes in that mythology the

symbolic entry point of the African disapora."

Blackshear's Alex Haley-Kunta Kinte Foundation is a half-million dollars away from realizing his dream in seeing-is-believing statues. But, with the city's approval and $170,000 from city, county and state, he's already gone a long way in recalling to life the legend-making history of this spot. If you keep your eyes open, you'll find a bronze tablet marking the likely location of the old auction block. The tablet, laid in 1981 by Alex Haley and Gov. Harry Hughes, was raised on a pedestal to be more noticeable and rededicated under Blackshear's orchestration and with city and private support last September 29.

Some modern history was made that day, in a simple handshake between two men of very different heritage. Reaching across the tablet from one side was the patriarch of the Haley family, George - the older brother of writer Alex, who died in 1992. The Haleys are, of course, descendants of Kunta Kinte.

Grasping Haley's hand was Orlando "Lanny" Ridout IV, of St. Margarets. Ridout's own ancestor was Kunta Kinte's auctioneer. The date was the 230th anniversary of Kunta Kinte's sale into bondage.

"If they can look each other in eye knowing what was done to whom by whom," says Blackshear, a 54-year-old telecommunications entrepreneur, "what possibilities does that open up for America?

"Racism did not start in Annapolis," Blackshear adds in rising oratorical cadence. "But reconciliation did."

Preserving African American Heritage

Spots as potent as City Dock for African American heritage are all over Chesapeake Country. Our region is as rich in - though far less known for - African American history as colonial heritage.

The first slave transaction in what would become the United States was recorded in Jamestown, Va., in 1619. Underground Railway conductor Harriet Tubman was freed from slavery near Bucktown in Maryland's Eastern Shore county of Dorchester. Editor and abolitionist Frederick Douglass begins the narrative of his life - which began in slavery - with these words:

"I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about 12 miles from Easton, in Talbot County, Maryland."

On the Bay's Western Shore, a few miles south of Annapolis, Douglass summered in his later years in Highland Beach, a community founded by his son and daughter-in-law. African Americans were not welcome in white Chesapeake Bay beach communities.

Benjamin Banneker - the black scientist whose knowledge ranged from the heavens (he was an astronomer) to the earth (he was Pierre L'Enfant's second in laying out the District of Columbia) - lived and farmed in the tiny black Baltimore County community of Oella.

The African American history associated with many such spots has been nearly forgotten, like distant memories. But in this decade, the potential for tourism is putting many African American landmarks on the map, often saving them from obliteration, as well as adding new African American chapters to the partially told stories of many old, familiar places.

Some of the developers are heritage groups, like Historic Annapolis Foundation. Others are African American entrepreneurs, congregations and civic groups, each - like Blackshear - inspired by a dream. Backing many of the projects is government money.

One of the early victories of African American heritage conservation is the Banneker-Douglass Museum, Maryland's state museum dedicated to preserving the state's black heritage. You'll find it on Franklin Street in downtown Annapolis, in one of the city's oldest black churches. In the early 1970s, the Mt. Moriah AME Church was about to fall under the wrecker's ball to give the county room for a bigger courthouse. From the battle to save it - fought by the community, the Historic Annapolis Foundation and the city of Annapolis - was born the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture, which in turn founded the museum.

Which in turn has collected a treasure house of the African American experience, including Arctic explorer Herbert Frisby's memorabilia; rare books, records, documents and oral histories; historical artifacts illuminating the everyday lives of black Marylanders; paintings and sculpture by black artists; and portraits of notable Marylanders.

Now on display at Banneker-Douglass is a rare collection of Benjamin Banneker's possessions (their later ownership is itself a dramatic story) and a show of African American quilts. (Open Tuesdays thru Fridays from 10 to 3 and Saturdays from noon to 4 at 84 Franklin St., Annapolis: 410/974-2893.)

The relationship between the state, which runs the museum, and the Annapolis African American community, who are its godparents, is not always smooth. For example, when a popular director was fired last year, controversy erupted and old fears re-ignited. But despite friction, Banneker-Douglass stands as a living monument to what has been achieved with community inspiration and state support - as well as a model for new endeavors.

Movement with Momentum

Today, African American heritage preservation is a movement with momentum.

On June 9 - after a decade of planning - a very different project bearing Benjamin Banneker's name will open in Baltimore County. Banneker lived his whole life in the tiny black community of Oella, dying in the same house where he was born. That homestead is now the center of the Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum.

Saved from development for tract housing, the 142-acre park is "exceptional as an historical archaeological site," says Baltimore County's Director of Recreation and Parks, Steven Lee, because "the land has never really been developed beyond agricultural use."

Archeology saved the site, Lee says, "discovering it as the actual place where Banneker lived, and that led to whole establishment of this project." In turn, archaeology will be a main theme at the new park, with a site at his cabin and sites for training young people.

"We are also trying to develop a replica of his farmstead with a reproduction log cabin and type of farming he did, with orchards and beehives," Lee said.

Most of the 142 acres is wooded and will be preserved as a conservation park for native American species. For active recreation, the park has a biking trail, following an old trolley line to the Patapsco Heritage Greenway.

In the museum will be historical exhibitions on the history of Banneker and early Maryland life plus a community gallery.

With such developments in place or progress in other parts of the state, Baltimore must have felt a little like Cinderella.

Two hundred years ago, Baltimore was the capital of free blacks in America, with Upton one of the nation's earliest middle class black neighborhoods. Over the years, the city has been a more or less friendly home to some of African America's great names:

Heroes of the culture have not gone without notice in Baltimore. Bluesman Eubie Blake's home is a museum and cultural center. Coppin State College, one of Maryland's historically black schools, founded Cab Calloway Jazz Institute in memory of the mid-20th century entertainer.

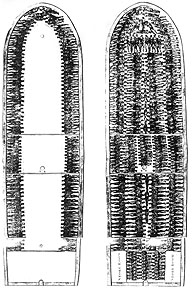

Many of Baltimore's other notable African Americans live on at the Great Blacks in Wax Museum (410/563-6415), the 15-year old enterprise of Elmer and Joanne Martin. Captured in tableaux there alongside sharecroppers and slaves are Frederick Douglass; singer Billie Holiday, Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall; Arctic explorer Matthew Henson. Joining the museum's replica slave ship is a new exhibit on lynchings.

In planning is a waterfront maritime park commemorating the careers of Frederick Douglass and of Isaac Myers, founder of Chesapeake Shipbuilding Company and of the first African American labor organization in American, the Black Caulkers Union.

With Baltimore's African-American Heritage Guide (get a copy of the free brochure at any branch of Enoch Pratt Free Library) you can guide yourself on a Baltimore heritage tour. Visitors who make advance arrangements can also take four-hour bus tours of Baltimore's rich Black history on African American Renaissance Tours (410/728-3837; see calendar for this month's grand tour).

Nowadays, the city is working in earnest to make its heritage tourist friendly. "We're really just starting to capture all this information and move it in a way that will help us share it. We have dedicated funding that's allowing us to turn up the volume on our efforts on leisure travel," says Carroll R. Armstrong, president of the Baltimore Convention and Visitors Association.

Adds city Director of Planning Charles Graves: "As we celebrate 200 years of rich history, we feel that preserving our African American landmarks and doing what we can to maintain them makes sense from not just a historical but also an economic development perspective. "

But for all its rich heritage and willingness, Baltimore has had no African American attraction in its tourist-rich Inner Harbor.

Come 2001, a new African American museum of national scope will rise on the Inner Harbor, at Pratt and President Streets, a district where entertainment, retail and other venues developed in traditional African American community. At this stage, planning is underway and a pair of Baltimore architectural firms have been chosen to design the museum.

Baltimore's Maryland Museum of African American History and Culture, the project of Del. Pete Rawlings and Maryland's Black Legislative Caucus, was authorized by Gov. William Donald Schaeffer in a 1994 executive order.

First in his order, Schaeffer recognized Maryland's rich "African American heritage ranging from Mathias deSousa [the first known black in the Maryland legislature] to Thurgood Marshall, and from the Underground Railroad to the modern civil rights movement."

Then he authorized a Maryland Museum of African American History and Culture Commission. Which in turn created a museum.

How the new museum will mesh with the Banneker-Douglass museum has been a subject of much debate. "We have worked hard since the summer of '96 with the staff, foundation and Friends of Banneker-Douglass Museum and their commission," says Nikki Smith, director of Historical and Cultural programs at Maryland Historical Trust.

"We think that Banneker-Douglass will focus on individuals and heroes in the community, while Baltimore will focus on families and communities within the state. Visitors will be encouraged to go to both," she said.

In this decade, it's estimated that African American heritage tourism earns multimillion dollar - some say billion dollar- annual revenues. That fact was not lost on shrewd former Gov. Schaeffer, who concluded in his '94 executive order that our state and citizens "can derive substantial benefit from the collection, preservation and public interpretation of our African American heritage, including cultural and educational benefits, and economic development in the form of increased tourism."

Read those fine-sounding words to mean that history is not only a resource but also a rich one.

Facing Our Shared Past

Rediscovering African American heritage means that at some point all of us, black and white, must reckon with the specter of slavery and its taboos.

In Chesapeake Country, the telling of African American heritage began in Colonial Williamsburg, Jamestown's cousin settlement. There in 1980 African American historian Rex Ellis broke the barriers of silence, adding to living history interpretation the unspoken story of the slaves on whose backs America's colonial culture rests.

Today Colonial Williamsburg's well-developed program in African American culture continues year round with lectures, walking tours that include slave quarters, costumed interpreters, historic dramas, music and dance.

"We also have a strong outreach program," says Christy Matthews, director of African-American interpretations for Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, who travels to our region to introduce audiences and historians to the African American experience.

"Often it is not simply a matter of integrating the Black experience into existing history because the Black experience often changes that history significantly," said J.W. Gardner, of the London Town Foundation, after the Southern Maryland Museum Education Roundtable met with Matthews for a workshop last November.

London Town's former director, Susan Gearing, began efforts to discover and report the African American side of 17th and 18th century life at the historic South River ferry crossing.

Further along, thanks to some serendipitous archaeology, is Annapolis' Charles Carroll House. Some 220 years ago, Charles Carroll became the only Roman Catholic to sign America's Declaration of Independence. As he contemplated its weighty assertions, his slaves managed their own declaration of independence.

Under the floors, at hearths and in northeast corners, they buried magic bundles, continuing a religious tradition carried with them from Africa.

As similar bundles - containing crystals, white buttons, pins and, at

Carroll House, the head and limbs of a doll - were recognized throughout

the Chesapeake region, including at Annapolis' nearby Slayton House, and

as far as Texas, diviners' bundles have become keys unlocking a story lost

for centuries: how, in the words of Carroll House director Sandria Ross,

"slaves practiced their freedom, fusing their traditional faith with

what they learned here."

Much of the story of African American heritage in Annapolis - including Carroll House's diviners' bundles - has been uncovered by University of Maryland archaeology professor Mark Leone. Digging with his students in the historic district of Annapolis since 1990, he has excavated five sites dating from 1790 to our time.

Many of Leone's excavations and discoveries belong to what he calls the "archaeology of slavery."

"The diviners' bundles," Leone explains, "belong to the religion of hoodoo, which was invented in conditions of slavery and probably as much in response to it as to African culture. In secret and under circumstances of oppression, people were practicing something they could consider their own religion, a religion of divining the future, healing and protecting against harm."

Because of its diviners' bundles, Carroll House - which is owned by priests of the Roman Catholic Redemptorist Order - has begun to add African American elements to the living histories it dramatizes for modern-day audiences.

They'll stage such an event Feb. 20, with audiences first learning about the dramatic discoveries of Annapolitan Joan Scurlock, then moving through the unrestored house by candlelight to small "stages" where costumed interpreters dramatize the stories of Carroll House slaves (tours from 6-8pm by reservation: 410/269-1737).

"A lot of colonial houses depict just the wealthy owners; you don't get much feel for slaves or indentured servants who worked there," says Scurlock.

"But when I started doing genealogy research on my husband's family, I discovered just how involved African Americans were in Annapolis even in colonial times. I've found a great deal of information at the Hall of Records - letters, inventories, manumission documents, even a lady who is herself a descendant of Carroll family slaves," she continued.

"There is a lot more to be found, and we're interested in soliciting people in the community who may add to the search."

Up from Slavery

A "major contribution to the archaeology of freedom" is how archaeologist Mark Leone describes his discoveries at Annapolis' Maynard-Burgess house. Under black ownership for most of its 150-year history, the two-story house at 163 Duke of Gloucester Street tells a story of African American success.

"John Maynard became one of about 20 free African American land owners in Annapolis when he bought this property. Maynard, who was about 35 years old, had already purchased the freedom of his wife, her daughter and her mother. Maria Maynard was a washerwoman and John Maynard a waiter, probably at the City Hotel." That's what you'll hear at stop #3 on Historic Annapolis Foundation's African American Heritage walking tour.

You can visit many spots on the road from slavery to freedom in Annapolis on the Foundation's fast-paced one-hour walking tour of historic sites of a city whose population has been one-third black for 200 years. Starting from the Kunta Kinte memorial at City Dock, the 15-site cassette tour climbs Duke of Gloucester Street, rounds Church Circle for the Banneker-Douglass Museum, heads down West Street to Calvert to Northeast to tour a traditionally black, much razed neighborhood. Through the Capitol, it takes in St. John's College, the U.S. Naval Academy and, at Paca House, the old Carvel Hall hotel. ($5 at the Foundation's Visitor's Center on Main St. at City Dock: 410/268-5576.)

While you're touring, you won't want to miss Annapolis' first statues commemorating African Americans. Too new to be on the Historic Annapolis Foundation's audio-walking tour, the Thurgood Marshall group is the city's most visible tribute to African American heritage. A bronze Marshall in the prime of life stands tall. Around him, forming a circle, are words describing the achievement of Brown v. the Board of Education, the case he argued before the Supreme Court to end school desegregation. Seated on benches considering their emancipators are three school children, two in one group, one in the other.

The Marshall group, dedicated in October of 1996, was created by Maryland artist Toby Mendez, whose concept was selected from over 120 others in a nationwide competition. It was conceived by the Legislative Black Caucus and funded by the General Assembly as a counterbalance to another Capitol statue, that of U.S. Supreme Court Judge Roger Brooke Taney, the Marylander who wrote the 1857 Dred Scott decision concluding that slaves were not United States citizens but rather their masters' property.

"The Caucus didn't think people should try to forget about those times in our country, but they thought we should also remember times have changed, so they suggested balancing the scales by dedicating a memorial in honor of another great Marylander," says Nikki Smith of Maryland Historical Trust.

You'll find the Thurgood Marshall group on Lawyer's Mall, to the north of the State Capitol. That, ironically, is where the Ku Klux Klan is scheduled to march Feb. 7.

As you visit with Marshall and children he freed from "separate but equal" schools, remember the future appointment you have with Alex Haley and his trio of listening children.

This month, as Black History is commemorated, opportunities abound to get closer looks at African American heritage. NBT will run a special section in its Good Bay Times calendar listings throughout February

| Back to Archives |

VolumeVI Number 5

February 5-11, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |