Rebecca T. Ruark Rises

Rebecca T. Ruark Risesby M.L. Faunce and Sandra Martin

Rebecca T. Ruark Rises

Rebecca T. Ruark Rises

by M.L. Faunce and Sandra Martin

Captain Wade Murphy's First-Person Story of Loss and Resurrection

O Captain! My Captain! our fearful trip is done.

The ship has weather'd every rack, the prize we sought is won

-Walt Whitman

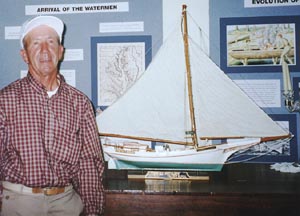

photo by M.L. Faunce

Everybody knows by now that Maryland's oldest skipjack, the Rebecca T. Ruark, sank to the bottom of Chesapeake Bay near the mouth of the Choptank River a few weeks back.

The subsequent resurrection of the 113-year-old oyster-dredging sailboat we call a skipjack here on Chesapeake Bay has as much to do with friends as with fate and faith.

Here's the first person story of Rebecca Ruark's captain, Wade H. Murphy Jr.,at right, as he recounted it to a rapt audience at Captain Salem Avery House Museum in Shady Side on a recent night

"I'd rather dredge than anything else," Murphy began, speaking to a standing-room-only crowd over coffee and dessert. The captain has worked the water for 43 years, and his face, as red and shiny as a cooked crab, bears witness to the weather's will. For all those years, he's crabbed in summer's blistering heat and dredged for oysters in biting winter cold. In between, he's made a living chartering his fishing boat, Miss Kim, and captaining cruises on Rebecca T. Ruark.

It's all hard work, but none of it harder than dredging oysters under sail.

"It's hard, back-breaking work, and you don't make much money. If I didn't like sailing so much, I wouldn't do it," he said. "There's nothing prettier than harvesting oysters under sail when there's oysters to harvest and you've got a good boat and a good crew."

They'd had a pretty day that November 2, dredging about 70 bushels, a whopping harvest for our times. The day's work done, Murphy's three-man crew had lowered and reefed Rebecca Ruark's sails to get her ready for the next day's work. That's the custom, Murphy explained, because it's easier to unreef a sail now than reef one later.

The seas churning up about 3pm that afternoon were not pretty. Never in 43 years had the wily old captain seen Chesapeake seas like those.

"It was the biggest sea I've ever seen in my life," Murphy said about the day winds were clocked at 60 mph and the Rebecca T. Ruark foundered in 20 feet of water, spilling both crew and all those oysters into the 50-odd degree waters of the November Bay.

The crowd held tight to his every word.

Going Down

Seas turned rough, very rough, the second day of the 1999 oyster season.

We finished dredging, and it was kind of rainy, with 20-mph winds. I left the upper Choptank river at 3 o'clock, which is normal - and thank God, because it would have been dark and they probably couldn't have found us. I probably wouldn't have been here tonight.

I quit earlier because it was bad weather. It was winds like 20 or 25 mph from the south. We were under power about two hours from Tilghman, and we had a lot of open water to go across to get home.

The normal thing to do, Murphy explained, would be to hurry home under sail. "It doesn't matter. Forty- to 45-mph winds are no problem" to Rebecca Ruark, he said.

So when you finish working in the protected waters, you pull your yawl boat up out of the water, because it will sink in a minute in rough waters.

A yawl boat, by the way, is the little motorized push-boat allowed by Maryland's odd law regulating oyster dredging to push the much larger skipjack to its oystering destination. In 1965, the law was loosened to allow yawl boats to push the skipjacks as they dredge on two days a week. The remaining days, they must dredge under sail.

"So you pull the yawl boat up, you put your sails up and you sail fair wind," Murphy continued.

We hauled the yawl boat up, and we started sailing to Tilghman. I've done it hundreds of times in the last 40 years.

I listened to the weather forecast. I never pay a bunch of attention to it, but I always check it because sometimes they can warn you of a storm. So I listened to the weather and the weatherman said, 15-, 20-, 25-mph winds from the south, rain, no heavy winds. In the lower Bay off Virginia waters, there's 40 mph, but no wind in the middle and upper Bay.

So we started sailing home and right in the middle of the Choptank, the wind breezed up more. It went from 20 to 25 to 30 to 35. Then it was blowing like 40 mph.

No problem. We were still on fair winds.

Then it started blowing more, and they clocked it at 60 mph. We were still going okay - until it started blowing the sails away. My sails were only two years old. It blowed the sails away and it was like the biggest sea I've ever seen in my life. It was rougher than I've ever seen it in the Choptank.

So the only thing to do now is anchor. Because if you keep going with those sails, you're going to be broadsided and you're going to get swamped.

I dropped the anchor; the anchor held her head to the wind. Then it started breezing up more.

She started diving her bow under. Sometimes there'd be water up on my forward deck up to my waist. My crew was scared to death.

No wonder. Many a Marylander takes to the water without ever having learned to swim. Two brothers made up part of the crew that day. One could barely swim; the second could not swim at all. "They'd been with me three years," said Murphy. "Now both those guys say they'll never spend another day on a skipjack."

Hands in motion as he talked, the captain's small frame swayed and rolled like he was still riding the deck of the Rebecca T. Ruark. But the captain, like his ancient skipjack, knows something about survival. Equipped with old-fashioned instinct and a modern cellular phone, he called his wife.

"So I called my wife on my cellular phone and told her where I was and that I needed somebody to come tow me and get somebody out there as soon as she could," Murphy continued.

So she went to see a couple of watermen right away and they started to come out. But in the meantime, the boat started taking on more water. The crew was so scared.

Murphy's eyes are small and intense, maybe from squinting all those years, sun-up to sunset, out in the wind and waves of the open Bay. Peering out from under a white peaked cap, he wears a look a little like Lucille Ball's look about which Desi Arnez used to say, "You've got that gleam in your eye." But Murphy's eyes grew serious as he recalled just how scared his crew was.

I said, 'You've got to keep the water out of this boat. If not, she's going to sink. She's taking on water.' Now on the Rebecca Ruark, we have two 35-gallon pumps. I said, 'Keep the pumps running, and she'll be all right.'

I didn't know they were so scared. They weren't even checking the pumps.

They said, 'The water is gaining over the pumps.'

So I said, 'You'd better start bailing because if you don't bail, she's going to sink.' They couldn't even bail they were so scared.

I got up there - of course she was anchored - and I bailed until I couldn't bail no more - without realizing the pumps weren't pumping.

Working frantically, Murphy kept his skipjack - the boat he calls a "good boat" - afloat until rescue arrived.

The people got there, and they started towing us in. About two miles from Tilghman she just took so much water over the bow, she went down.

It washed the life ring off before that happened. It blowed that off the boat, and all the life jackets were in the cabin. We had seven survival suits in the cabin, but I couldn't get to them. There was a life ring on top of the cabin and it got off a little distance.

I couldn't believe she was going down. She started down and I thought she was going to come back, and she never did. And I got off of her.

I made it to this life ring, and about that time, one of my crew, a big fat boy, popped up alongside me and grabbed the life ring, and I said, 'shoot!'

Murphy knows about as much about showmanship as about captaining. At the image of the fat boy sharing a single life ring, laughter flows through his audience, breaking the tension.

"And it did hold us both up," Murphy continued.

There was so many lines floating around, we had to get away from the boat so a boat could pick us out of the water.

The other two guys were up front, holding to the rigging. The brother who couldn't swim at all held on to the boat when she was starting to go down.

Again brother watermen came to the rescue.

"Thank God, they're good watermen," Murphy continued, seeming to shiver remembering the cold and wet.

They were just waiting to get clearing, and the tide this night was 10 to 12 foot. When the rescue boat backed up to get these two boys off the bow, one of them grabbed the life ring that was thrown to him, and they brought him on the boat.

The boy who couldn't swim was so scared he was holding on to the boat. They threw him a life ring and he wouldn't take it, he was so scared. They threw it to him again, and he wouldn't take it. The third time they were screaming, and finally they pulled him on the boat and I thought for sure he was going to get drownded.

That life was not all Murphy had had to worry about. The Island Girl had hauled Rebecca Ruark quite a way, but when she went down, the tip of Tilghman Island was still a distant blur.

"I can swim," Murphy confided after the mesmerized crowd had taken their story home from Captain Salem Avery House. "But not that far."

Coming Up

Once he and his men were safe, Murphy's mind turned to the plight of his boat. He bought the Rebecca T. Ruark, his second skipjack, in 1984, spending $80,000 to get her into working shape. Now his beloved boat, his investment and livelihood, lay beneath 20 feet of water. He had to get her back.

"We got into Tilghman and it blew so hard, we couldn't get back to the boat," Murphy continued. This was, he declared, "A freak wind in freak seas."

The next day, I got two towing companies and we'd almost get her up but just couldn't get her high enough to pump her out. We did this till dark, and we had to give up.

Those were Murphy's lowest hours. A third-generation waterman, he'd kept the faith while others abandoned it. And he'd kept it pure. Dredging under sail in 100-year-old wooden boats is not the only way to harvest oysters. But it is the hardest way.

When you're dredging oysters under sail, on a windless day you wouldn't even get expenses. The closest oyster bar to Tilghman is two hours, so if you got the crew to go on a sail day, you leave the dock at 5 o'clock. They leave their home at 4 o'clock, you get to the oyster bed at sun-up, 7 o'clock, and if there's still no wind, you sit there half a day, then you still got two hours home.

Now, he thought, it was all up. Even if he could get the weather to raise his boat, where would he get the money? One commercial estimate was a whopping $30,000.

But Captain Wade Murphy was not without friends.

Well, they had a meeting that night, some kind of political meeting about something else, with a lot of people there. I have to give Levin [Captain Buddy] Harrison [of Harrison's Chesapeake House on Tilghman Island] credit. He told the people that this boat was sunk, and if she wasn't gotten up in a day or so, she was going to wash to the beach.

This was the oldest boat in the Chesapeake and they ought to try and save it, he said.

They told me that within two hours, the governor okayed the crane to come from Baltimore.

Harrison's message leap-frogged from the Maryland Department of Business and Economic Development to the Governor's Office of Business Advocacy to the Maryland Port Administration.

"Once the Port Administration knew the clock was ticking, they moved as quickly as they could," said Maryland Department of Transportation spokesman Jack Cahalan. "Within hours, the decision had been made to assist and logistics worked out on how to assist.

Three days after the old Rebecca Ruark sank, the state committed "roughly $10,000 to $12,000" to Baltimore company Martin G. Imback Inc. to raise her.

"So they left Baltimore that night, November 4, at 9 o'clock," Murphy continued. "The next morning at 6 o'clock, they went and raised the boat."

Divers secured the boat to the boom of a heavy-lift crane, which, Cahalan reported, "very slowly, very methodically and very carefully brought the Rebecca Ruark back to life."

"If it wasn't for that," said the skipjack's captain, "I don't know if we could have got her or not."

Standing on the bow of a sinking boat suddenly gives a person a new perspective. So, apparently, can seeing her rise again.

"Usually bureaucrats don't work that quick," declared Murphy, who, his tone suggested, had seen just about everything now.

This is something that's got to be okayed by a lot of people. That's why I guess the Rebecca Ruark is so important to them. They did the job, and I'm thankful.

Afterword

Time was, skipjacks dominated the oyster fleet working Chesapeake Bay. Murphy tells the story of that fleet as if he had seen it with his own eyes - as did his grandfather, who came to Tilghman Island and began a career as a waterman in the 1880s.

"In 1885, after they had 15 million bushels of oysters harvested, everybody wanted to go oystering. The state law said that you must have a sailboat to harvest oysters. So, in 1891, somebody designed the skipjack. With its flat bottom, straight sides and hard chine, any backyard boat builder could build a skipjack," Murphy said. As many as 600 were built to ply these waters and reap an amazing abundance of oysters.

Rebecca Ruark is an anomaly among her kind. Built in 1886, she is a round-chine boat. Which makes her a rarity among rarities.

As we leave the 20th century, only 10 working skipjacks remain. That small Chesapeake fleet is America's last fleet at work under sail.

"So," says Murphy, "it's important to save this boat."

Rebecca Ruark's distinctive construction also makes her a piece of work when it comes to repairs.

"If she was a typical skipjack with straight sides, it would cost one-third the money to rebuild her," says the captain, who's now looking at a repair bill at least as big as the $80,000 he spent on initial repairs.

More to do the job right - not just patch her up with glue and bailing wire, as has been so often done in Rebecca Ruark's 113-year past.

"I could patch this boat up right now and go to work in a couple of weeks. And if it had been 20 years ago and I had babies home to feed, I wouldn't even hesitate," says Murphy. "We'd have got her up on Friday, we'd have worked till midnight Friday, Saturday and Sunday, and Monday and we'd have been sailing. We'd have just patched her up. And the next year, we'd patch her up again."

But this year - when the loss and recovery of the Rebecca T. Ruark coincides with the fleet's selection, by Maryland Commission for Celebration 2000, as Maryland's Treasure of the Month - is different.

"After you get so many patches," says Murphy, "you can't patch up some more. She's going to die.

"Instead of patching her up, I'm going to stay home this winter and get the boat fixed so maybe your children and grandchildren will be able to sail on the Rebecca."

That, readers, is an appeal. Send your donations to restore old Rebecca, a Chesapeake Bay treasure, to: Rebecca T. Ruark, 21308 Phillips Rd., Tilghman, Md. * 410/886-2176 * www.skipjack.org.

Skipjacks Officially a Maryland Treasure

Skipjacks are November's Treasure of the Month in Maryland.

The Treasure of the Month designation is part of Save Maryland's Treasures, the state's millennial effort to recognize and preserve its endangered historic resources.

As well as honor, the designation throws skipjacks a life preserver in the form of the Save our Skipjacks Task Force. The task force's recommendations, due in January, 2000, are expected to include -

| Issue 47 |

Volume VII Number 47

November 24-December 1, 1999

New Bay Times

| Homepage |

| Back to Archives |