I Gave My Ghost His Due

I don’t need psychics to convince me that ghosts are real.

My own ghost supplies all the proof I need.

The ghost homed in on me five years back. He’d had his eye — metaphorically speaking — on me for years. But it took some time to woo me to his cause. (As everybody who has ever watched a ghost movie knows, ghostly powers are latent, depending on a living being to summon them.)

We had our first encounter in a graveyard, James Andrew Smith and me.

On a sultry Memorial Day a half-century ago, I was visiting a hilly, blackberry-ringed burial ground with Miss Cora Smith, my grandmother’s close cousin. This was home territory to Cora. She was born and lived much of her life only a mile up that dirt and stone road. Much of her family awaited her in Wilson Cemetery, where her gravestone, engraved with her name and birth year, presumed her arrival.

As we wandered through the old graves, watching our footing on the uneven ground, Cora talked about mother and sisters, aunt and cousin, all buried there. These were people I had known in the flesh, though all except for cousin Florence, my grandmother, I knew as distant elders.

Then Cora introduced a stranger.

“I lost my only brother to the river,” she said. A shiver of old, remembered grief jumped from her to me.

The lost brother had no tombstone in Wilson Cemetery. No story passed down in family legendry. No footnote in Mississippi River history.

He had disappeared from Earth and record. Perhaps his body sank into the cold and snaggy depths of the Father of Rivers. Perhaps he washed far downstream, tumbling in the turbulence of current and riverboats. Perhaps he fed giant catfish slugging in the river’s silt.

Cora joined the family in Wilson Cemetery in 1971. Her estate went to auction, carried out piecemeal to bidders on the sagging porch and little lawn of her rustic frame home. To me came my frugal cousin Cora’s savings — a dowry for Bay Weekly — and a lifetime of letters.

For decades, my cousin’s century of letters moldered in whisky boxes in basements and closets, following me from Illinois to Maryland.

I had spent four decades writing other people’s stories when a demand rose up from the grave — or from the river. Cora’s stories were mine to tell — and I had better hurry, their ghosts insisted, to give them their last chance at life.

When at last I opened those boxes, Cora’s lost brother reached for me. Among the hundreds of letters, six were penned by his hand on pulpy paper softened over 100 years. Some of the softening may have come from wear, as they were read and reread by James Andrew Smith’s mother and his youngest sister Cora, who became their caretaker. I in my turn was their third reader. As I read, James spoke as if from life.

The Ghost Speaks

“I saw a man killed last Sunday night, just beat to death,” the 20-year-old wrote his mother in his first letter from St. Louis chronicling his search for work in the big city. “I run in and made him quit and he drew a revolver on me. I tell you I was scared.”

That Sunday — March 18, 1894 — was not James’ date with death.

Over the next months, James recorded his falling and rising hopes as he sought his way in the world. He was “scared,” he was “lonesome and homesick,” he was “disheartened.”

By August 30, six months after his arrival in St. Louis, he was “fine as a fiddle.” His hopes were high. Anticipating a new job — “$30 a month and board and only eight hours a day” — he looked forward to a brightening future.

Then his letters abruptly stopped.

Cora’s one-sentence elegy told me why: “I lost my brother to the river.”

James — who got so short a span of life — wanted more for his requiem.

Much of his story unfolded in his letters. My research added context. Going further — tracing one insignificant man with the ordinary name of Smith through 125 years of randomly recorded history — took all the digging skills I’d learned in my lifetime of reporting. Plus human kindness and good luck.

James arrived in a city reeling from the Panic of 1893. Times were hard, and a boy seeking his future away from home earned no special dispensation.

Hub of rivers and railroads, St. Louis was America’s fifth most populous city, swelled to 452,000 in the 90 years since Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery followed the Missouri River into the great open west from the trading village of 1,200 frontier folk. Railroads never bothered with James’ rural Illinois county, a peninsula in many ways like Calvert County.

The country boy judged the big city “an awful tough place.”

Work was scarce. Trouble was not. The murder he’d witnessed made him nervy.

“I want to get away from here,” he told his mother.

He planned to escape to Kansas City — if his mother could finance the trip. Then fate gave him another way off the mean streets of St. Louis.

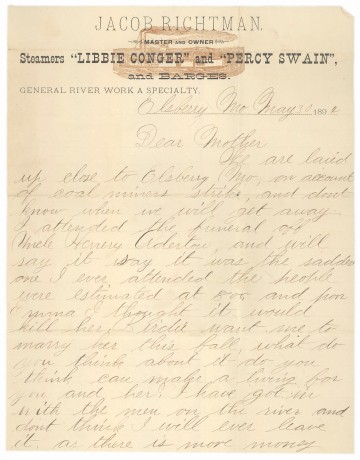

“I have got in with the men on the river and don’t think I will ever leave it as there is more money in that than any thing else,” he wrote. That work brought him close to home, along the Mississippi at its meeting with the Illinois and Missouri rivers.

Starting in May, James worked with Captain Jacob Richtman, “Master and Owner Steamers Libbie Conger and Percy Swain. And Barges. General River Work a Specialty.” James wrote on Richtman’s letterhead and received his mail in care of Richtman.

That spring, a nationwide coal miners’ strike begun April 26, 1894, halted commerce and blocked James’ promising path.

With Richtman’s boats idled, James looked elsewhere for work. With the Army Corps of Engineers hard at work taming the big rivers of America’s heartland, James wrote that he was “thinking of changing and go on a government boat that is working near Alton Ill.”

The move would be a step up. “I am only getting $20 a month with board, while the other boat offers me $30 a month and board and only eight hours a day,” he wrote his mother. “I think that is better don’t you?”

James Smith was a young man with responsibilities, so making good money was important to him.

“Birdie wants me to marry her this fall,” he advised his mother. “What do you think about it? Do you think I can make a living for you and her?”

He and his girl spent the Fourth of July weekend in their hometown. For the holiday, itinerant photographer Frank Woodard had set up in Batchtown, where James bought himself a stylish cabinet card portrait.

“The next time you hear from me you will be surprised, for when at home Birdie and I had my pictures taken,” he wrote his mother. “I will send you one as soon as they come.”

With the portrait in the mail, James wrote again, pride bursting from his words.

“I want you to answer as soon as you get this and tell me what you think of your boy, and if you don’t think he is the best looking child you got.”

“From your boy,” he wrote, signing himself James A. Smith Esq.

That letter, dated August 30, 1894, would be his last.

What James did over the next three weeks made all the difference in his world. For that decision led to his death.

That September, James Andrew Smith, 20 years and 11 months old, lost his life on the river.

Digging up My Ghost

That far, James’ story was mine for the finding. In the clutter of his sister Cora’s papers were not only his letters but also a scrap on which she’d penciled family deaths. Among them was James: September, 1894.

From there it was all digging, with his ghost goading me to dig deeper, dig wider. With each excavation, I saw more of the world James knew. I encountered others who shared his name but came to their own personal tragic endings. My James Smith remained unchronicled in his time and forgotten by history.

Find me! his ghost admonished, as if a jot of remembrance in the world of the living would ease the loss of a lifetime.

At last, a source at three degrees of separation, way in the outer circle of my geography of connection, found my first cousin twice removed.

One of a legion of local historians, a stranger named George Giles lifted himself from his comfortable chair on a September afternoon to help me dig.

He found this newspaper story, dated October 5, 1894.

“James Smith of near Batchtown Illinois fell from a boat at Sterling [Island] on Friday afternoon and drowned. His body was recovered Sunday near Turners Landing and he was buried Monday at Hardin.

Smith was a watchman on the boat and said to have been a most exemplary young man. He was to be married to a young lady and she is almost prostrated at the sad event.”

The young lady would have been Birdie.

Instead of a wedding, James had a funeral. Instead of walking down the aisle, he was carried into Calhoun County’s Hardin cemetery, where his father had lain alone for 12 years.

As his body decayed to dust, his 20 years and 11 months of life faded into the ash of memory.

In the slower time of 1894, that story was likely two weeks behind the fact. The Friday of James’ death would have been September 21. That was the day, 125 years later, that George Giles gave me the ending of James Smith’s story.

Ever since, James’ ghost has treated me gently.