I Thought I Knew Where I Lived

Bristol is a town barely in Anne Arundel County. It’s also barely clinging to an identity as a town, if the U.S. Postal Service has its way.

The name Bristol is recognized as authoritative in the county’s southwestern corner by most maps, by the U.S. and Maryland Geological Surveys, by the Maryland Department of Planning, by countless county databases and by the Maryland State Highway Administration’s maps and big green highway signs.

But not by the postal folks. To them, Bristol doesn’t exist. To them, it’s all Lothian in southwest Anne Arundel County.

The USPS opened a new building in December 1997 right between Bristol and Waysons Corner, inexplicably using neither name. They instead called it Lothian — though it was over six miles from Lothian, real Lothian, that is — one-quarter mile east of the Rt. 2-Rt. 408 traffic circle according to all these sources. This left some in bucolic Bristol with an identity crisis that is, at best, confused and, at worst, lacking a sense of place.

They’re not alone.

Other Bay Country readers are also in search of their own town-identity, from Lower Marlboro (nowhere near its USPS designation of Owings), to Fairhaven (proudly independent of Tracys Landing), to Heritage Harbour (not really part of Annapolis.) Your real town identity can perhaps best be found on paper or online maps by the Maryland State Highway Administration (roads.maryland.gov/Town_Gridmaps/100000_Anne%20Arundel.pdf). Or, if you’re keen on confirming that with coordinates, at Geonames.USGS.gov.

Both will confirm for folks on the West River that they’re not really in Harwood; for those at Lyons Creek that they’re not in Lothian; and for those on Jewell Road near Friendship that the USPS designation of Dunkirk is just silly (and not even in the right county.)

Does the post office really have authority over one’s town name?

We asked one person who would know. Jennifer Runyon is the senior researcher on the Domestic Names Committee of the U.S. Board on Geographic Names. She pointed out that for all U.S. states and territories, it’s not the USPS but her committee, via its official repository, the Geonames site, “with staff input from the U.S. Geological Survey” that “is the authoritative source for geographic place names.”

“In 1906,” she explained, “Teddy Roosevelt granted the committee the authority to standardize and promulgate all geographic names, including populated places.”

“Twenty states or so (including PA, NJ, NY) have towns or townships, all with distinct boundaries,” Runyon added, in clarification of Maryland’s oddity. Only a small portion of Maryland is similarly covered by incorporated towns or cities.

For their part, USPS officials have gone on record to say that zip code town names “were never meant to indicate town boundaries but rather just to allow the mail carrier to deliver mail.”

Back to Bristol

As for Bristol, the county-owned nature sanctuary, some residents and some news media all incorrectly list Bristol’s physical location as Lothian. That means visitors punching just Lothian into a Google Maps app wind up on a wild goose chase seven miles in the wrong direction. These visitors and readers are not putting a stamp on themselves and jumping in a mailbox, yet they’re inexplicably handed the zip code name (Lothian), not the real location as found on maps and on highway road signs (Bristol). Likewise, punch in just Tracys Landing, and you’ll never get within five miles of Fairhaven homes carrying Tracys Landing addresses. And so on.

“The name Lothian does not reflect where we live,” said former Bristol Community Association president Ken Riggleman. “It’s like saying Annapolis and Severna Park are the same place; they’re eight miles apart, the same distance from my house in Bristol to (real) Lothian.”

From the 1970s to recent years, the Bristol Community Association has mobilized to defeat developers in true David vs. Goliath fashion. The list includes stopping a trailer park on Jug Bay’s shores (now a nature sanctuary); stopping the largest East Coast sand and gravel company’s 645-acre quarry and processing plant proposals (now part of that sanctuary); helping to stop a Target-anchored 30-acre mall (now a park); stopping a mega-church’s development of a 57-acre facility; and in 2014 stopping a takeover each fall of a 225-acre Bristol farm by a festival’s quarter million visitors.

“It was Bristol that sounded the alarm and galvanized opposition on each of those,” Riggleman added. “It’s a shame to wipe out historical references to Bristol just in the name of USPS economic expediency.”

Regardless of what you call it, Bristol used to be a big deal. Steamships and trains called twice daily. Bristol was more prominent than adjacent Waysons Corner until the mid-1960s (when the future uncrowned king of Vegas gambling magnate Steve Wynn was still calling bingo numbers there.)

Bristol Landing or Pig Point has been on our maps since the late 1600s, and on 1814 British army maps. The Pig Point Post Office began in 1807. Claims that the name refers to the pig iron shipped downriver from Snowden’s furnace are fraudulent, as the town and its name easily pre-date any furnaces. In 1871, that name was apparently censored as undignified. Leon was substituted.

Post offices were popping up at an alarming rate in 1895. The Baltimore Sun on February 2 reported that “There will be nine post offices within six miles” of Bristol’s post office, counting the new Drury post office.

Drury? Well, in the Jan. 12, 1961, Evening Capital, a Bristol resident reported finding under a horse-drawn carriage seat 1862 Civil War love letters by Robert Pindell to his future wife back in Bristol, Fannie Drury (plus “his disappointment at her negligence in answering his letters promptly”). Both Robert and Fannie’s last names found their way onto our maps, both adjacent to Bristol.

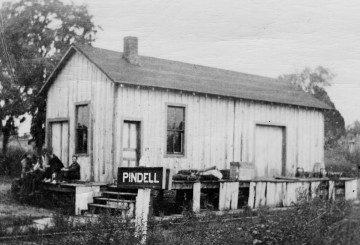

At Pindell today, only ruins of the station and store-post office remain from the 1899 Chesapeake Beach railroad. In 1975, county official Amy Hiatt wrote that, after the trains stopped in 1935, “the community dissolved.”

That their communities “dissolved” might come as a surprise to the current thousand or so residents of the Bristol-Pindell-Drury area. Yet the almighty zip code seems to have a firm grip on how some residents and media identify hometowns in Bay Country.

In 1999 Bristol’s Gertrude Trott wrote that she was “born in a community called Blue Shirt on what is now Mallard Lane” but added that it was “now in the Lothian area.” Yet Lothian is actually eight to nine miles away. Isabelle Sunderland Plummer that year wrote that she had lived in Bristol, which is now Lothian. Confusing at best.

Our Sense of Place

Robert Michael Pyle wrote in The Thunder Tree that most people seem to require a “sense of place that gets under our skin,” needing a “place of initiation.” Some people develop a much keener sense of place than others, such as Upper Marlboro’s Mary Kilbourne who passed away on October 20 at the age of 83. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Baywatcher of the Year in 1995, their Conservationist of the Year in 1999, and the 2005 Jug Bay Award-winner, Mary was most connected to the Jug Bay-Bristol-Croom part of the Patuxent River. She had as solid an identity as anyone with a “place” — the river and its adjacent marshes and eastern hardwood forest in her case.

Perhaps to one degree or another we all need such a place — even when we’re many miles away — a place upon which we can reflect, one for which we might even get a little homesick.

Sure would be nice if we knew what to call that place. We might just have to settle for home.

David Linthicum is a retired geographer with the U.S. Department of State Office of the Geographer. His last name is a place name.