| Deborah Hanson Greene’s Watercolor Safari

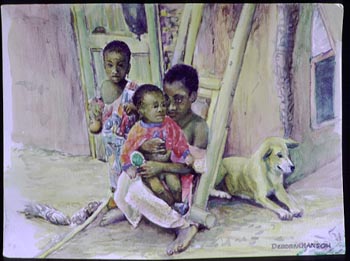

Artist Deborah Hanson Greene, above left, used her African trave ls as inspiration for a new art exhibit, African Images. ls as inspiration for a new art exhibit, African Images.

What would you sacrifice for your dreams?

For her eight-month odyssey through Africa last year, artist Deborah Hanson Greene sacrificed her dream job at Ballet Theater of Annapolis, where she’d spent five happy years as general manager. The dancers themselves partly inspired Greene’s bold move. “I admired their pure dedication,” she says. “They sacrificed for their dreams.”

Greene’s husband Bill was the other inspiration. The brand of extreme traveler featured in outdoor adventure magazines, Bill Greene has hiked along the Thailand-Burma border, gone sea kayaking and dog-sledding in Alaska and scuba-dived all over the world. But he’d never been to Africa.

“We didn’t want the traditional two-week safari,” says Debbie Hanson Greene. “We wanted to really experience Africa.”

The couple took the plunge and gave up their jobs.

“It was a hard decision, says the 1974 Vassar graduate, who began her career writing grants for the Menominee Indian tribe of Wisconsin. “But Bill is 61 and I’m 47. We wanted to do this while we were young enough. Camping around is hard on a body.”

Artist Greene captured her African adventures in her exhibit, African Images, on display at 49 West Gallery and Coffeeshop till March 31. African Images presents a series of vivid watercolors of the people, wildlife and stupendous scenery of Africa.

The couple explored the continent with a series of small truck expedition outfits. “You have to be physically fit for these,” Greene explained. “If the truck gets stuck, you’re expected to help dig it out.”

Or even get it across a river, as Greene and her party managed to do. Two years and many leagues away, among the paintings of her 49 West exhibit hangs a photo of the frazzled but cheerful artist in the Cameroon jungle with a hearty band of fellow travelers posing at the foot of a bridge they have just built.

“We had to do it,” Greene said. Grinding through miles of dense foliag e on a narrow, muddy path, the group’s truck was stopped cold by an unfinished bridge. “On a road like that we couldn’t back up,” Greene said. “The only choice was to finish the job ourselves.” Luckily, whoever started the job had left the lumber. “With all of us it only took a few hours,” said Greene. e on a narrow, muddy path, the group’s truck was stopped cold by an unfinished bridge. “On a road like that we couldn’t back up,” Greene said. “The only choice was to finish the job ourselves.” Luckily, whoever started the job had left the lumber. “With all of us it only took a few hours,” said Greene.

Trucking was tough, but it let the Greenes experience Africa close up. The couple camped in a different place most every night: an olive grove overlooking Roman ruins, a rubber plantation, a mango orchard, a villager’s roof and behind a Sahara dune, where the desert winds roared over them. Sleeping under the stars brought them closer to more than just the land: “One morning we woke to find ourselves surrounded by jackal footprints,” Greene said. “They’d come and sniffed us as we slept.”

Sometimes tents became a necessary precaution. “There’s nothing separating you from the animals. There’s no fences,” she said. Though you might suppose lions or elephants to be the kings of the forest, in the game preserves wardens instruct visitors to zip their tents tight against hippos. “Hippos look really cute,” Greene says, “but tourists are killed by hippos more than any other animal. I guess they stomp over people.”

In all, Greene and her husband trucked through, trekked over and bivoucked in 21 African countries. “That’s 21 customs offices,” Greene sighs.

Greene chose as a motto for her exhibit a classic line by Marcel Proust: “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.” As a visual artist, she took Proust’s words almost literally.

“I was already painting in bright colors before seeing Africa,” says Greene, who has shown her work locally more than 15 years. “But now those colors are truer. This trip gave me time to really look at the colors in landscapes,” she said. “My teachers had encouraged me to forget what we’re taught about colors in grade school: that grass is just green and tree trunks brown. Some trunks actually have pink in them. A trip like this helps you see these things simply because you have time to see them.”

The clothing and ornamentation sported by villagers inspired Greene. “Since I’m already attracted to bright colors, the Africans really turned me on in that way,” she said. “They might not have much to work with, but they love bright colors, and they look beautiful.” Greene’s warm portraits of the Africans she met are among her favorites and also her biggest sellers. (All works are for sale.)

“This is my way of showing people how wonderful Africa is,” Greene said.

Death to Mosquitoes

Alaskans jokingly call mosquitoes their state bird. While things don’t grow as big in Maryland, most of us still take cover when mosquitoes whine around.

To spare us the itch of those devilish insects that give us bumps in the night, Maryland’s Department of Agriculture is beginning an “integrated pest management” campaign against mosquito larvae.

“Aerial applications of the larvicide Bacillus thuringiensis israelensis will occur primarily in Southern Anne Arundel County,” says entomologist Patricia Ferrao. Spraying will be targeted to large woodlands, swamps and marshy areas difficult or impossible to treat using ground equipment. Ferrao emphasizes that spraying will not be done over houses.

The larvicide Bti is a “naturally occurring soil bacterium producing toxins that don’t affect wildlife, fish, domestic animals or people,” Ferrao says. “Bti is lethal to the larvae, causing an imbalance in its gut.

“Beginning in March, aerial applications, may significantly reduce the use of insecticides for adult mosquito control in your area,” the entomologist adds.

Spring Bti spraying is different from summåer spraying by truck or by individuals equipped with backpack sprayers. Ground spraying is used to reduce an adult mosquito problem. When people call and report a problem around their home or neighborhood, the department will test the area.

Field technicians arrive about dusk, when mosquitoes tend to be active, and stand still to be bitten for about two minutes.

“If a landing rate of five mosquitoes in two minutes” is found, Ferrao says, the pests are deemed a nuisance and the Department will fight back. Spraying is done only by community request.

The killing chemical is permethrin. Permethrin is one of America’s most commonly used insecticides, applied on a vast range of crops from papayas to pistachios. Despite its wide use, permethrin is classified as highly toxic to fish and therefore it carries warnings to “keep out of lakes, streams and ponds.”

Permethrin spraying is aimed at adult Maryland native swamp-loving mosquitoes. It’s not effective against tiger mosquitoes, which breed in standing water that collects in clogged gutters and old tires.

But this spring, if you hear buzzing overhead, it may just be the whine of a twin engine aircraft overhead applying larvicide — and not the whine of a pesky mosquito.

Mosquito killing is not a predictive science, so Ferrao is not able to say how bad the mosquito problem will be this year. If you’re overwhelmed come summer, call Mosquito Control at 410/841-5870.

The Bird Man of Route 665

photo by Mary Catherine Ball

Bird Man Bob Williams feeds, sometimes by hand, a flock of vultures he’s attracted to his Annapolis home.

At dawn and sunset, an ominous flock settles into a cluster of barren trees at Aris T. Allen Boulevard and Chinquapin Round Road. Coragyps atratus, locally known as black vultures, turn the neighborhood into a Stephen King smorgasbord featurin g raw beef and chicken parts. g raw beef and chicken parts.

They are — and have been for three years — the guests of Bob Williams, 61, known to his neighbors as the Bird Man.

Twice a day, this Annapolis native feeds the feisty frenzy of voracious vultures. “I just find them fascinating,” Williams said. “They were flighty when they first came around, but now they eat out of my hand.”

Vultures are not the most agile flyers. And, with enormous six-foot wingspans, they prefer trees with few branches. Williams has stripped down a backyard tree for the big birds’ roost.

Williams’ fascination with vultures goes beyond observation. In his aerie (decorated with dozens of gargoyles), he showed me a video of himself mingling with the winged beasts. Seventy-plus vultures engulfed the Bird Man and his porch.

“They don’t bite or scare me,” he said, undaunted. “I just walk outside and call ‘Here, buzzy, buzzy,’ and they surround me like chickens.” Meat-eating chickens.

Bob’s family pets seem to like the birds as well. “The dog and cat will walk right into the flock, and they don’t mess with each other,” he said.

One bird has won Williams’ particular affection. Crippy has been dining at Bob’s home for years. “She’ll come right into the house and eat with me,” Williams said. Crippy got her name from the bow in her left leg.

Some neighbors tell Williams they believe the vultures are “omens,” and that if he continues to buzz with them, the birds are sure to “get him.”

The birds, maybe. The neighbors, no.

There are no laws against feeding vultures, says Maryland Department of Natural Resources wildlife biologist Glenn Therres. But, as with any wild animal, you run the risk of interrupting the natural cycle of a species by providing them with food.

Vultures are scavengers and generally won’t bother anything living. So don’t be alarmed if you’re stuck in traffic on 665 and a giant menacing bird circles your car. Unless you drive a meat truck.

Mid-Winter Waterfowl Count Closes ‘Mixed’

Original scratchboard by Gary Pendleton

Like the stock market, the annual waterfowl survey finished mixed th is winter. The count, which includes all species, came in at 911,800, up from 881,100 in 1999. is winter. The count, which includes all species, came in at 911,800, up from 881,100 in 1999.

Conducted in Maryland each January since the 1940s and standardized in the 1950s, the visual count is an estimate. “But it’s not an estimate of population size,” says Maryland Department of Natural Resource’s waterfowl biologist Larry Hindman. “We’re really tracking trends, to see if waterfowl numbers are up, down or stable.”

Waterfowl stay put in winter, so surveys are conducted all across the country at this time.

In Maryland, two pilots in two planes with two crews and two observers follow well-worn aerial routes over six days in January. From the all-Plexiglas cockpit of a Cessna 185 with floats, observers from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and DNR view waterfowl from an elevation of 250 to 500 feet. That’s as close-up and personal as you can get in a plane.

Computer programs assist the tabulation.

Here’s what they found — minus blinks:

- Dabbling ducks (widgeons and pintails) 93,200, compared to 93,000 in 1999;

- Diving duck, 241,200 compared to 229,600 in 1999;

- Goldeneye (9,100), bufflehead (15,500) and redheads (5,300) all up slightly;

- Scaup (96,100) up significantly;

- Ruddy ducks high, though not as abundant as in 1999, when 84,000 were observed.

Total duck estimates declined to 341,300, compared to 348,800 in 1999.

How can observers be so sure about their count? The January survey is intense preparation followed by routine action.

Each year, the same routes are followed by the same people using the same methods. Hindman has scoped out waterfowl in the same Upper Eastern Shore territory since 1975. Nothing, he says, was different this year — “except the snow squall that grounded us in Gaithersburg. I had to rent a car to get home.”

Survey results showed one “most unusual” development. The snow geese count rose to 150,700 from 110,900 in 1999. For the first time, snow geese were counted on the Chesapeake Bay in Eastern Bay and along Kent County. The white geese are expanding their range — from Worcester County — and their diet to include corn, soy beans and winter wheat.

Canada geese were mixed. Favorable nesting conditions in Canada led to heightened expectations. But this year’s estimate of 396,400 came in nearly identical to last winter’s 396,700.

When you’re observing Canada geese in your neighborhood (or golf course), don’t confuse migrants with residents. Resident geese are genetically different: They’re larger and lay more eggs. Originally purchased from the Midwest as live decoys to attract migrant geese, their numbers keep growing despite their use as decoys being outlawed way back in 1935. The resident population now numbers around 60,000.

Last but not least, particularly to those of us who live along the Bay and nearby rivers and creeks, are tundra swans. The annual waterfowl survey provides the only population estimates for this important species. Tundra swans in Maryland numbered 15,600, unchanged from last year.

Teaching a Sense of Adventure

After nine months in the classroom, what teacher wouldn’t want three months of travel and adventure?

One lucky Maryland teacher will interrupt the school year with a three-month voyage to eight ports of call aboard Maryland’s Goodwill Ambassador, The Pride of Baltimore II. In memory of the teacher chosen to ride the shuttle into space, the Christa McAuliffe Fellowship for the Teacher Aboard Pride of Baltimore II has been funded by The Maryland State Department of Education. The voyage will begin this August.

During this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, the McAuliffe fellow will explore ports of call throughout Scandinavia. There’ll be a final stop in Portugal before heading home across the Atlantic. Schools and places of historic importance will be stops along the way. Like the crew, the teacher aboard will have a job: promoting cultural understanding among middle school students and school-to-school partnerships across the Atlantic.

The fellow will keep a log describing cultural experiences and sailing adventures aboard a tall ship. This record will be posted on the Internet along with digital and video pictures for easy reading over the school year.

In 1998, the first Christa McAuliffe Fellowship went to Leslie Anne Bridgett from Waldorf. “For a teacher, this is the ultimate experience. This is really what teaching is all about,” Bridgett said.

To apply, you must have taught full time for at least eight years at the middle school level.

Applications are due by March 31. Learn more at www.pride2.org or contact Darla Strouse: 410/767-0307.

In AA County, No Yard Waste Pick-Up Til April

When burgeoning daffodils muscle through layers of matted leaves on their way to the sun and sprouting daylilies compete with fresh weeds for room to grow, you know it’s time to start cleaning up your yard.

That time is now. But don’t expect those bags and bundles of nature’s litter to be whisked away by county workers within a few days.

Anne Arundel County stopped collecting yard waste at the end of January and will not resume the service until April 1.

A couple years back, the county cut back from year-round to 10-month yard waste pick-up. “Relatively little yard waste was placed at the curb during” February and March, said public works spokesman John Morris.

About 17,300 tons of yard litter is collected in the other 10 months.

In the meantime, county recycling programs manager Beryl Eismeier suggests you try composting leaves and storing bagged and bundled debris until April 1. If you forget and leave your yard litter, even if bags are marked with the tell-tale masking tape cross, they’re likely to be snatched when trash is picked up.

If you just can’t wait, then leaves and debris can be dropped off at one of the county recycling centers in Lothian, Glen Burnie or Millersville.

Way Downstream …

In Virginia, Gov. Jim Gilmore signed an agreement last week that will pay farmers $90 million to plant trees and grasses on environmentally sensitive farmlands along the Chesapeake Bay and other waterways. The aim is to reduce by 650,000 pounds the amount of Bay-choking nitrogen from fertilizers that would otherwise be dumped on crop land …

In the Alabama town of Bay Minette, Ron Horton has no intention of letting Alabama Power Co. trim his prized oak tree. He quit his job to stand guard and said last week that he’ll stay in the tree and may even get married there. We wonder if they’ll insist on taking chain saws to wedding boughs …

In California, people snickered when the David and Lucile Packard Foundation declared in 1998 that it would rescue 250,000 acres of land from bulldozers and asphalt by the year 2003. They weren’t laughing last week when the foundation announced that it had reached its goal in two years — spending tens of millions of dollars to preserve 271,000 acres of open space, an area the size of Los Angeles …

In Britain, the World Wildlife Fund has introduced a new label called “Fish Forever,” which is intended to preserve seafood from overfishing. Already, 100 seafood buyers have pledged to use the label, which indicates that products weren’t harvested from overfished waters …

Our Creature Feature comes from India, where there’s a new unemployed work force — elephants. The Los Angeles Times reports that hundreds of elephants have become jobless in the aftermath of a court ban on commercial logging in India’s northeast. Most loggers have gotten jobs but their flop-eared beasts of burden are, we gather, queuing up in free-peanut lines.

Said Padmeshwar Doley of his creature named Bahadur: “Never in 35 years has my elephant seen such bad days.”

Copyright 2000

Bay Weekly

|