For most of a century, Smith Building Supply has supplied Southern Anne Arundel’s boards, nails and answers. For most of a century, Smith Building Supply has supplied Southern Anne Arundel’s boards, nails and answers.

By M.L. Faunce

From his second floor office overlooking Deale-Churchton and Shady Side roads, Jack Smith has a window on the world. Outside is the world you could say he helped build, board by board, nail by nail, in the 49 years he's operated a small lumber and building supply business on six and one-third acres in rural Southern Anne Arundel County.

At age 76, Smith is poised to move on: to "change careers," as he puts it. But the niche Smith created through hard work, goodwill, quality products and personal service won't be easy to fill. In half a century, Smith Building Supply has been a full-service, one-stop general store for an area that was isolated in the early days and still off the beaten path.

Customers ask him, "What are we going to do, Jack?" Smith doesn't have an answer. That's a first in many customers' experience. "A lot of people are even mad at me," he allows, "because they won't have the service they're used to here."

For once, the man whose wife says he "never says no to anybody" is thinking of himself. At three-quarters of a century, he's retiring and selling out. He's got too much more to do and too little time to do it in.

For now - and even he doesn't know how long now will be - Jack Smith continues to do what he does best. That's what separates his business from other building supply companies, including the giant 'box' stores where you can get most anything you need to build, decorate, clean, even furnish a house - except that personal touch. You can learn how to do it yourself at today's big stores, but you can't get an expert to do it for you.

Stacked on a drafting table in Smith's plain-paneled office are a pile of blueprints for residential and commercial projects. "I'll go through those plans and tell them how many 2x4s and nails and hardware to buy. I always thought of this as a service that brought in business and that differentiated me from Home Depot as well as some of my smaller competitors," he explains.

"Mom and pop businesses" like his $6 million-a-year enterprise are, Smith muses, an "endangered species." Says he: "We're a very small business, lumberyard-wise."

Still, Smith doesn't believe his retirement needs to be the end of Smith Building Supply. He insists there's a "real opportunity here for someone to operate a small lumberyard to serve the homeowner and do-it-yourselfer. A business like his could survive nicely," he says - if it's designed to take care of the local community, which is what most people say he has done. But, he says, "building a strong, viable business in today's world" is going to take someone younger than he is.

The Making of an Institution

Back in the 1950s, Jack Smith was just that ambitious young entrepreneur. His inspiration, he says, came from his father, J. Edward 'Eddie' Smith, the oldest in a family of nine. In 1925, Eddie and his brother Nelson had opened in Galesville a company that survives to this day: Smith Brothers Pile Driving and Marine Construction. All six brothers worked in the business. Like everyone else, they struggled during the Depression.

World War II raised their fortunes, Smith recalls. "There were jobs and there was work to do, a lot of government work, for example at the Naval Academy, and the family established a good reputation, which carried them."

The war changed young Jack Smith's fortunes, too. Then a student at Western Maryland College, he joined the Navy and saw the world from Attu Island, a harsh place at the end of Alaska's Aleutian Island chain where armaments were loaded on ships of the Northern Pacific fleet. He returned home, finished college and went to teach math and science in a Baltimore County high school in what he remembers as "a very good situation in a good country school."

As the older generation of Smiths neared retirement, they bought the William Thomas Lumber Company, at the crossroads of Churchton and Shady Side, descendant of a lumber business that had been going since 1921 and at its present location since 1935.

When the family asked Jack to be manager, he agreed, opting for a life in a small business. "And you can't get much smaller than this," he says of the business he and his wife still work at seven days a week.

"To show you how astute a young man I was," he jokes, "I left a teaching job making $2,800, working five days a week 10 months a year to earn $2,500 a year working six days a week 10 hours a day for 12 months a year."

Marie Murphy, the Baltimore County girl who would become Jack's wife of 51 years, got her look at rural Anne Arundel County in the late 1940s. "Transportation was the biggest shock," she recalls. "I was used to walking to get a streetcar to go shopping downtown, and we could walk to a big grocery store. When we moved to Galesville, I had to learn to drive, and the roads weren't that good. We had a few country stores. They all gave credit. People would buy on credit during the winter and pay their bills during the summer when they crabbed. That was the advantage of a small store and that way of life."

The lumberyard that came to be called Smith's continues under family ownership to this day. Stockholders are Jack, Marie and three cousins. All are in their 70s, and all but Jack "are ladies. I guess you could say I'm in the minority now," Smith chuckles.

Business as Usual

Arthur Foote has worked at Smith’s for 48 years. He calls Jack Smith boss and friend.

Marie Smith has worked side by side with her husband since 1968, seven days a week, but only half days lately. She's in charge of the money end of the business nowadays, but in the beginning she had to get to know "everything: windows and doors, block and brick, plumbing, electrical and housewares."

The Smiths haven't done it alone. "We think we're all kind of like a family," Jack Smith says. "We have some here that we had two, three, four from the same family, which I'm very proud of." One such family is the Thompsons. Father Lionel works in the yard, and son Glenn is a truck driver. Over the years, Smith says, he has never had to advertise for workers. When positions opened up, someone in the yard or the store knew somebody looking for work.

Arthur Foote, 65, has worked at Smith's for 48 years, starting in the yard and driving delivery trucks, moving inside as sales clerk when walk-in trade increased. Today, he'll take your order or help do-it-yourselfers find their way through paint and brushes, nuts and bolts, electrical tape, W-D40, bird feeders and electrical tape. Bags of mulch and topsoil are piled high outside in the yard, and sheds are full of lumber, including Smith's specialty, a number-one grade of pressure-treated lumber direct from Madison Wood Preserver in Madison, Virginia.

"I've got to keep a full inventory," Jack Smith says. "Otherwise people will think we're slacking off."

Service hasn't slacked, either. For instance, you can get your chain saw sharpened or repaired at Smith's.

James "Puddin" Creek, with Smith's for 45 years, runs one of Smith's workshops repairing kerosene heaters, and reglazing and windows and doors. "If your dog jumps through the screen door," Jack Smith explains, "he will repair that."

In the carpenter shop, self-taught master craftsman and millman Dave Turner can custom build a colonial-era cabinet or create a frame for an obsolete window, as he recently did for a stained glass window for Centenary United Methodist Church. "Dave is quite an authority on colonial architecture and furniture," Smith says, adding that the preservationists at the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis often rely on Turner and his expertise.

Customers like Audrey Mae MacWilliams, retired postmistress of Churchton, have shopped at Smith's for decades. "If they don't have what you need at the store, they'll get it for you," she says. Helen Gorham of Shady Side has found everything she needs at Smith's - even before it was Smith's. It's so "convenient," she says, stocking up on furnace filters.

Today's clientelle mixes shoppers like MacWilliams and Gorham with professional contractors. That's a different mix than in the 1950s, when 90 percent of the business came from commercial contractors and Smith's sold only lumber.

"There was little in the do-it-yourself market," Smith recalls, "and no market at all for lawn and garden." Back then, a small hardware store complemented the lumberyard. By 1968, Smith had tripled the size of the hardware store.

"Hardware has become an increasingly important part of our business because I wanted to carry everything the building supply contractor and the homeowner would need," Smith says. His office - bare floors, paneled walls, tidy desk and drafting table - is as straightforward as he in his crewcut and blue oxford shirt. Only a small, darkened computer screen tells you that this is not the 1950s. The phone rings incessantly, his door is open, customers and workers file in and out with questions and problems, which he handles calmly and methodically, never changing the tone of his voice. "Hardware has become an increasingly important part of our business because I wanted to carry everything the building supply contractor and the homeowner would need," Smith says. His office - bare floors, paneled walls, tidy desk and drafting table - is as straightforward as he in his crewcut and blue oxford shirt. Only a small, darkened computer screen tells you that this is not the 1950s. The phone rings incessantly, his door is open, customers and workers file in and out with questions and problems, which he handles calmly and methodically, never changing the tone of his voice.

Responsiveness to changes large and small is part of what has kept Smith's thriving. "Whenever we have a drought," Smith says, "we sell a lot of hoses. In wet weather we sell sump pumps. Once, during a big oil shortage when prices were high, we sold a lot of wood stoves and chain saws. This year has been a bad year on crab pots. Ordinarily, we sell around 800 crab pots to individual homeowners. This year we sold only about 300."

For decades, Helen Gorham has found what she’s needed at Smith’s.

Change Comes to Jack Smith

Finely attuned to change as he's been for so many years, Jack Smith didn't expect to avoid change himself. He intended to stay in the lumber business until he was 70. That, he says, is when he started looking around for people to carry on the lumberyard.

He still hasn't found that sort of buyer.

No one in the Smith family is standing in line to take over the business. Neither of their children, daughter Susan Cosden of Cedarhurst, a dental hygienist, or son Johnny Smith, a Shady Side waterman, is interested in becoming part of the business.

"Johnny doesn't want to be confined in a place like this - which is fine," his father says. "I respect both of them for finding their own way."

"We did have a deal working with another lumberyard, Smitty Lumberteria over at Alexandria, and we worked on it for two years," Smith continues. In the end, the Virginia Smiths said his yard wasn't big enough to be profitable.

And that's too bad, Smith says, because small businesses are vital to the nation's economy, employing more people in the United States than any other segment.

"So then," he says, "we went to the open market."

Eventually, Jack Smith and his partners accepted a contract with a Northern Virginia developer. Jay Donovan isn't interested in a lumberyard. He's looking to build a small strip shopping center with a chain grocery store of some 47,000 square feet.

Store Wars

In 1991, when Smith thought of retirement in the future tense, Safeway Inc. purchased land in Deale, barely three miles from his lumberyard. Time went by and paint peeled on the sign that touted "Coming soon: a new Market Place at Deale" as Safeway weighed the conditions, went over the hurdles of county zoning and purchased additional land on its site.

By the time Safeway began its push in earnest, Smith's neighborhood had changed. "People here didn't think of themselves as quaint, just hard-working, blue-collar people," Smith said. Now white-collar ex-urbanites were flowing in from Washington and its suburbs to an area they valued as unspoiled. Many were active in policy and politics, and they knew how to organize. From the new grass roots, activism sprang up.

Meanwhile, Anne Arundel County reached out to involve more citizens in its long-range planning. Where the two forces converged, opposition to development exploded. Safeway took the brunt of the opposition, and Smith's plans nearly ran aground.

As word spread that Smith Lumber and Building Supply was under contract, Smith learned that a civic planning committee had recommended downzoning his Churchton business from heavy commercial use , C-4, to light commercial, C-1.

The downzoning recommendation was made, Deale-Shady Side Small Area Planning Committee chair Ron Wolfe later explained, because "there was this fear of the size of our commercial complexes getting out of control."

Smith says that the change - which would permit a business to sell alcoholic beverages, have an art studio or a bakery, but not allow it to store lumber outside - would have been "disastrous" for him financially.

"C-4 is what I'd planned on for my retirement. Blood coursed through veins I didn't know I had," said Smith on learning of the proposed downzoning.

On a night early last spring, Smith went before the panel to plead his case against downzoning. "I wore a coat and tie out of respect," he says, and he "promised to give them the straight stuff."

Smith recollected that zoning came into existence in Anne Arundel County around 1954, when the W.M. Thomas Lumber company first applied for and received the heavy commercial zoning permit required for businesses using outside storage. Through expansion in 1968 and again at the time of the purchase of an additional acre of land, Smith applied for and received C-4 zoning.

"I thought what I had to do was uphold my end of the bargain and keep it a viable, commercial property," Smith said.

You could hear a pin drop in the overflowing Galesville Hall by the time Jack Smith finished addressing the Deale/Shady Side Small Area Planning Committee.

The committee voted to drop its recommendation to downzone Smith's property.

But the protests have had their effect.

"I think future businesses that might come here, food store or not, are looking at what's happening down here, and it has its effect on [my] developer getting tenants here when they see what's going on. As a result, I'm just sitting here. It's tough right now to run the business. I don't know how to plan."

Short-Range Planning

Smith used to have some 35 employees. Today there are only about 20 because, he says, "we're slowing down and pulling in our horns."

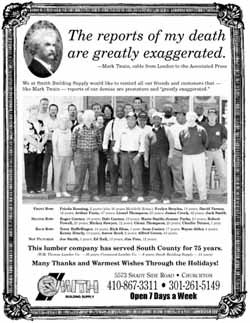

But in May of 1999, when the lumber company that serves South County celebrated its 75 years of service, Smith placed an ad, in the style of Mark Twain. "The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated," he advertised.

How soon will contractors and do-it-your-selfers alike have to find another source of hardware, garden supplies, mulch, lumber and such services as screen replacement and windows glazing?

"Well, I guess it will be the day we close the doors," Smith says, "which could be 40 days or 400 days, four months or 40 months, depending on what happens.

In February of 2001, the two-year option on his property expires. If the developer doesn't take up the contract, Smith says, then he'll start all over again.

James ‘Puddin’ Creek measures before rescreening a window.

Smith's Future

Jack Smith's next career is on hold until he sells his business, but ideas keep rolling for things he wants to do when he stops selling lumber.

Of what he's not going to do, he's certain. "I'm not going to quit working, and I'm not going to work for another lumberyard," Smith says.

The list of what he's doing and still might do keeps growing. Over Smith's desk hangs a hand-written plaque: The measure of a man is the depth of his convictions, the breadth of his interests, and the height of his ideals.

He first saw the quote he says he's tried to live by on the stage at Annapolis High School when he was 13 or 14. "I guess they sent us country kids up there for some culture, and it captured my attention and I wrote it down," he says.

Smith's interests are many. "I am kind of a closet environmentalist," he says. "I'm really interested in the Bay. Now, I participate in the oyster-growing programs with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and have oysters growing from my pier in Galesville. Next, I'd like to learn more about programs that have to do with restoring grasses in the Bay. Maybe work for a business that either sold or planted or had something to do with restoring the grasses."

This year, he got his Coast Guard Captain's license, an achievement to which he's long aspired. "He was the oldest in his class," wife Marie says.

He's also a sailor, a member of Ducks Unlimited and an active Southern Anne Arundel County Lion. Not to mention president of the Galesville Heritage Society. Smith's father, Eddie, compiled The Home News from Galesville -100 issues in all - keeping servicemen in World War II up on local happenings. Recently, Smith had The Home News reprinted for the Galesville Heritage Society. Now he'd like to publish a book of letters sent home by local servicemen during the war.

"He's always doing something," Marie frets. "He spreads himself thin."

The End of an Era

Neighbors are rushing the funeral, mourning in advance a loss they say will make their lives tougher and diminish their community.

To half-century employee Arthur Foote, Smith - who added benefits and health insurance to his job - is "boss and friend, just the same as a father figure."

To many, Jack Smith is the quintessential small businessman, fully involved with his community. He's served on local boards, volunteered his time and donated products and services to schools and libraries. Thus long-time customer Audrey Mae MacWilliams praises him as "one of the best people around because he does so much for the community."

On that evening last spring before the Small Area Plannin g Committee, chairman Ron Wolfe told Smith that "no coat and tie can further enhance the stature that you have in this community or the reputation or the honorable service that you have performed not only for the community, but for everyone who has ever been associated with you and who's ever worked for you."

But most of all, Jack Smith has helped a community get its jobs done. Richard Nieman of Shady Side, a general contractor for 26 years, says he can't imagine how it will be without Smith Building Supply, where he's bought all his supplies. "It's been a right good relationship," says Nieman. "I could always depend that he'd take care of getting anything I needed. And he has always been honest and fair."

Where will Nieman trade when Smith's closes? Nieman's answer: "I'll be traveling to Annapolis, I guess."

Copyright 2000

Bay Weekly

|