Black Maritime History Runs Deep

The ocean delivered millions of Africans into bondage, but it also buoyed hopes. Enslaved at a waterfront plantation, young Frederick Douglass watched boats on the Chesapeake Bay. “This very Bay shall yet bear me into freedom,” he later wrote. Douglass, who worked in a Baltimore shipyard and fled slavery disguised as a sailor, became a leading abolitionist and a statesman. He is one of many blacks whose fates and fortunes were steeped in maritime history, a saga largely undocumented.

Mystic Seaport Museum’s planned launch of an Amistad replica this spring, the formation of the Blacks of the Chesapeake Foundation and a spate of recent books hint at heightened interest in this legacy.

African American seafarers and watermen were a rare breed and a diverse lot. They crabbed, hauled in menhaden, shrimped with hand-tied nets, tonged for oysters and speared whales. They manned lighthouses, lifesaving stations, warships, paddleboats, privateers and even pirate ships. With unusual mobility, African American sailors navigated beyond the limited horizons of blacks ashore and served as conduits between far-flung black communities along the coasts and up and down the Mississippi River.

The waters did not wash away the color line, though. Thousands of blacks were sailors, but few commanded vessels. Those who did made waves. Massachusetts shipbuilder Paul Cuffe, a leading advocate of colonization, took 38 blacks to Sierra Leone on his ship in 1815. Captain Absalom Boston, a free black born in 1785, headed an all-black crew aboard the whaling schooner Industry and amassed substantial real estate holdings.

Emboldened by the desire for freedom, some blacks seized control of vessels. Aboard the slave ship L’Amistad, Joseph Cinque and 53 other Africans staged a mutiny, leading to the 1841 Supreme Court ruling that liberated them. In 1841, slaves revolted aboard the Creole and sailed to the Bahamas, where they were freed by the British.

During the Civil War, African Americans launched perilous naval missions. Robert Smalls was a slave and deckhand on the Planter, a cotton steamer leased to the Confederate Army to transport arms and provisions. In 1861, with seven black crewmen and their families aboard, Smalls steered the Planter past deadly mines and Confederate forts and into the Union fleet.

That same year, freeman William Tillman, a steward and cook on the S. J. Waring, a schooner captured by a rebel privateer, single-handedly killed the rebel crew and sailed the vessel to New York. The federal government gave Tillman a $6,000 reward.

The Union Navy admitted African Americans in 1861, almost a year before the army opened its ranks. Some former slaves risked their lives to enlist, swimming or rowing boats from plantations to Union ships anchored nearby. Eight African-American sailors won the U.S. Medal of Honor for their courage in battle.

Despite such valor, blacks were barred from the Navy after World War I and not allowed to enlist again until 1932 and then only as messmen. In 1942, the Navy accepted volunteers for general service but prohibited them from going to sea. In 1949, Wesley Branch became the first black graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. And in 1996, Admiral J. Paul Reason became the Navy’s first black four-star admiral.

African Americans also served honorably in the Coast Guard and its predecessor services, the Revenue Cutter Service, U.S. Lighthouse Service and U.S. Lifesaving Service. From 1887 to 1895, Captain Michael Healy commanded the cutter Bear, considered the greatest polar ship of its time. African Americans served at several U.S. Lifesaving stations. Pea Island Station in North Carolina, however, had the service’s only black keeper and all-black crew. Under the leadership of Pea Island Keeper Richard Etheridge, seven crewmen waded and swam to a shipwreck during an 1896 hurricane and saved nine survivors. Though white crewmen had received gold medals for less daring rescues, nearly a century passed before the crewmen gained official recognition.

For every tale of adventure and courage, thousands more black seafarers and watermen labored in obscurity, lured as much by opportunity as by love of the sea.

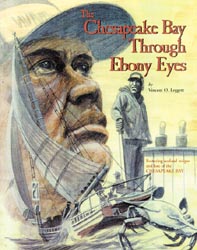

Want to know more? Read Black Jacks by W. Jeffrey Bolster; Black Hands, White Sails: The Story of African-American Whalers by Patricia and Frederick McKissack; Blacks of the Chesapeake and The Chesapeake Bay Through Ebony Eyes by Vincent Legget; and my own Sink or Swim: African-American Lifesavers of the Outer Banks.

Carole Weatherford lives in High Point, North Carolina. Her family also has a home near Easton on our Eastern Shore. Talk with her at [email protected].

Remnants at Crossroads

To be or not to be. That is the question.

For The Remnants.

As one of Annapolis’ hottest bands, Tom Fridrich, Tom Boynton and Tristan Lentz enjoy the spotlight.

But now at a crossroads, The Remnants contemplate their future and reminisce over their five-year history.

“We feel less emphasis on playing every little smoky bar now. We can be appreciated for what we do — whether performing, writing songs for other people or focusing on publishing deals,” Fridrich says.

Maybe they’ll move to Nashville.

The Remnants’ dreams are unfolding, but they must reach even higher and work even harder to make them come true. Will that mean emigrating to the country music capital?

“In Annapolis, there are any number of talented musicians who don’t have to leave. But we want a bigger slice of the pie,” Boynton says.

After releasing their third album, Songs for Sale, The Remnants ask themselves what it’s all about.

The struggle for radio airplay: They’ve gotten this wish from WRNR, a constant supporter of local musicians.

The chance to perform with national acts: They’ve gotten this wish, opening for Pete Droge and Fastball.

The rocky road of musical ageism: Boynton and Fridrich laugh across the distance between them and Ricky Martin, shaking his bon-bon.

The struggle against the industry’s fadism: That’s the theme of their new single, “The King is Dead”: We’re all burned out on this month’s flavor. Make us feel part of something BIG. If this is the revolution bring back the king. Can’t anybody here play or sing?

The Remnants think they can.

“We’re a great band. I’ve been in plenty of bands where I wasn’t sure I would have bought a CD with our songs on it. But not now. The Remnants still put a grin on my face,” Boynton says.

Music courses through their veins. They got hooked on the Stones and Beatles when kids listened on transistor radios.

But they’re getting tired, Boynton says, “of standing in the coldest part of Parole Plaza unloading our equipment at three in the morning.”

They’re not getting their share of the glamorous life of rock music. Fridrich spends his day as a theatre manager with Maryland Hall. Boynton restores old houses. Lentz works on boats.

The times they are a’changin’, and these men, now in their 30s and 40s, wonder what place the millennium holds for them and their ‘roots rock.’

They’re waiting for their turn to come. They’re getting impatient.

Find The Remnants at www.theremnants.com.

Soccer Local Kicks into World-Cup Gear

When most five-year-olds were practicing without training wheels on their bic ycles, Shane Malamphy was also training: training with his father to become a soccer star. ycles, Shane Malamphy was also training: training with his father to become a soccer star.

Now, seven years later, Malamphy has been chosen to represent the USA at the Gothia Cup, also known as the Youth World Cup, in Gothenburg, Sweden in July 2000.

Selected from over 1,100 players across the United States, this Southern Maryland player will join in the largest youth sporting event in the world, with 1,200 teams competing from 64 nations.

Head coach and organizer of the US team Clive Griffiths selects every player. A former player himself for Manchester United, in England — one of the most storied teams in soccer history — Griffiths also played in the USA for the Chicago Sting and the Kansas City Comets.

“In the 14 years that I have been selecting players, Shane is definitely exceptional,” Griffiths says.

Griffiths discovered the young Malamphy at an autumn try-out. “I had been told that there were players worth looking at in Maryland,” Griffiths says. “I select from all over the country, but I was very pleased to find the quality of players that I did right here in Southern Maryland, especially a player such as Shane.”

“Shane is an all-around team player. He is there with the hustle and with open ears and eyes. Shane is the first one to volunteer to help collect the soccer cones, and he never has an attitude.”

What’s his secret?

“I just love soccer,” Malamphy tells us. “It is always continuous action, not like with baseball, where you are waiting for play, or football with all the time-outs.”

A seventh grader at Southern Middle School in Lusby, Malamphy plays on several area soccer teams. “I do indoor soccer in Leonardtown and Baltimore over the weekends in the winter months,” the 12-year-old says.

If this is not enough to keep him busy, Shane has made the final cut for the Maryland Olympic Developmental program. It will be several weeks before he will find out if he makes the team.

In June, Malamphy will meet up with the other players chosen for the Youth World Cup team. “We will only have one week to practice and have a clinic before we will go to Sweden,” says Shane, and as he speaks you feel his excitement. Not only will he be playing the game that he loves; he will be traveling across the Atlantic for the opportunity of a lifetime.

And his dreams don’t stop there. “If we win the Youth World Cup, we will be titled the best youth team in the world. But it’s not over then. We’ll go back to England and prepare for the Umbro Manchester United International Futbol Festival,” the boy says.

If all of this sounds overwhelming, imagine what it will cost. His father, Mike, a soccer coach himself, says it will take $6,000 to make it happen.

Local events are being planned to raise the money for the Malamphys’ trip. Businesses are also donating.

“Many soccer fans are just so excited that a young boy from our area gets this extraordinary chance, they want to see him go and do well,” says Mike Malamphy. “But we are still very far from the needed amount.”

To help, reach the family at 410/326-0413.

From Rebecca Ruark’s Mast, a Flock of Decoys

The Rebecca T. Ruark sits high and dry these days at the Maritime Museum in St. Michaels. Back in November, the 100-plus-year-old skipjack spent three days underwater after sinking near the mouth of the Choptank River in a winter gale. Now, Captain Wade Murphy Jr. watches over his resurrected boat’s reconstruction.

The only skipjack of its type, built in 1886, Rebecca is now being “totally reconstructed,” her rotting timbers replaced with white oak framing from a lumber yard in Chestertown and pressure treated beams from Montrose, Va., which Murphy hauls in his truck as needed. New sails are being stitched by Quanom Sail in Annapolis. The Coast Guard keeps a vigilant eye on the boat’s restoration and will certify the vessel’s fitness to carry up to 35 pas sengers come this spring. “Everything has to be perfect,” says Murphy. sengers come this spring. “Everything has to be perfect,” says Murphy.

Perfection comes at a cost. It will take $50,000 to $60,000 to restore the Rebecca.

As usual, Murphy has a plan.

A 1920s’ mast of Oregon pine, which was scheduled to be replaced before the sinking, was stripped from the boat, cut into nine-foot sections and hauled to Havre de Grace. The captain says he found a carver, Charles Jobes, willing to take a “reasonable price” to turn the mast into 16-inch pieces from which to carve male canvasback decoys.

“Everybody said the male-only decoys won’t sell, that people wanted pairs, but I knew they’d sell,” Murphy says.

Murphy’s wife told him that the set price of $1,000 a canvasback sounded greedy. “I’m needy, not greedy,” replied Murphy, who once spent his life savings and mortgaged his worldly goods to save the workboat. The 82 decoys carved from the old mast, complete with a certificate signed by the carver and the captain with a picture of the Rebecca, will be offered at that price. Five will be held back for Murphy and Jobes’ children. The final five on the market will be sold at auction over the Internet.

All proceeds will go to restoring and maintaining what some — Murphy among them — call the “queen of North America’s last fleet of working sailboats.”

To restore his boat, Murphy will go anywhere to talk to anyone about the Rebecca and the waterman’s declining way of life on Chesapeake Bay. He says when a Rotary Club recently asked him to lecture for 40 minutes, he explained, “It’s not enough time.” This is a man who, by his own confession, “loves to talk about my boat and teach people about the Bay.”

Friends and family call Murphy Tom Sawyer. During oyster season, he advertises “give me $60 and I’ll take you out on my skipjack and you can cull oysters all day.” He gets a few takers. More come aboard to enjoy the two-hour sailing trips that Murphy, 58, and a third generation skipjack captain, run out of Tilghman. When Bay Weekly caught up with Murphy, he was passing out brochures to the sparse crowd of winter visitors in the Maritime Museum’s boatyard. The curled-up brochures went down with the skipjack, or so he says.

This Sunday, Dan Kilmon, Scott Ray and Tom Howell are spending their day off at work on the Rebecca. Murphy is still seeking an experienced boat carpenter willing to work for modest wages. Come spring, Tom Sawyer will be looking for painters.

Captain Wade Murphy picks up 82 painted canvasback duck decoys from Charles Jobes in Havre de Grace this week. To place your order, call the captain: 410/829-3976.

Way Downstream …

In Virginia, former Gov. George Allen’s spotty record on the environment will be a key issue in his drive to unseat Sen. Chuck Robb in this year’s Senate election there. News reports show that it may not be a factor yet: Allen (R) and Robb (D) are in a dead heat in a new poll, and Allen has raised twice as much money …

The Illinois General Assembly is up to monkey business again. After hearing passionate testimony from monkey owners, a House committee last week defeated a proposal to ban people from keeping “non-human primates” as pets. Said one chimp advocate, “Monkey people are a little different, and we know it” …

Our Creature Feature, which comes from Denmark, goes to show that the old Bass ‘o Matic from Saturday Night Live lives on. After complaints from animal-rights activists, police have ordered the power cut off to an art exhibit that features goldfish swimming in blenders.

They call it interactive art, which means that people are permitted to turn on the blenders to watch, shall we say, the water change colors. To fight back, activists have snatched some of the fish.

Copyright 2000

Bay Weekly

|