|

|

The Fearful Journey of Steve Ferralli The Fearful Journey of Steve Ferralli

by Kathleen Murphy

Steve Ferralli was as healthy as you or me when, out of the blue, his heart failed him. Now the Southern Middle School teacher is running on pumps and drugs, waiting for another tragedy to make him whole.

April 9 - Please solicit prayers from anyone and everyone you know. The docs have said that we need a heart to fall from the sky within the next 28 days.

With those words in an e-mail message, I learned the fate of a man whose life precariously depends upon the death of another. Steve Ferralli is on a fearful journey as those who know and love him are on an anxious mission to save his life. He lies in the Washington Hospital Center, his heart so enlarged he must wait for a new one. The doctors are unable to pinpoint just what caused this damage. As a mechanical pump keeps this man’s heart beating, he ponders this threatening life adjustment: “God sent me a curve ball, and I got to deal with it.”

A Man with Heart

Steve Ferralli, 46, a technology education teacher at Southern Middle School in Lothian, is the guy who lights up any room with his broad smile and caring ways. Here was a man of seemingly boundless energy, an athlete and playmaker. An active member of the school staff and member of the faculty council, he was a role model for new teachers and a man others depended upon for moral support and encouragement. Faculty meetings at the school end on an upbeat note with principal William Callahan asking Steve if anything’s missed.

Students who have come through Southern Middle School over the last 24 years smile when considering Mr. Ferralli. He is the firm yet fatherly guy, the one who loves to joke and tease. When it comes to learning, he is invested in teaching the students how to create projects on the computers, use the darkroom, design and build. One of his former students, Tony Jett, now a D.C. firefighter, remembers a teacher who “treated you like an equal.”

Ferralli is also the energy behind the yearbooks that are passed around with excitement each spring. From his hospital room, Steve queries co-teacher and longtime friend Al Miller about whether the books are passed out. He continues the drill, asking, “Did they make an announcement?” He looks at the yearbook brought to him and shows Al a collage page of student baby photos. Steve then instructs Al to make sure the original photos are returned to the students. The man whose own life hangs delicately takes time to think of others, those students for whom he cares so deeply.

At home in Calvert County, Steve Ferralli is the active parent of Philip, 16, and Bethany, 14, and loving husband of Sharon.

Steve and Sharon met at Southern Middle School as new teachers in Anne Arundel County. Steve offered to help Sharon move a bookcase in her office, and from there they became a couple.

Now Sharon waits patiently for a new heart to give her husband renewed life. Over these past weeks, she has taken on the role of hospital runner, advocate and go-between with the numerous doctors, nurses, specialists and technicians. When Steve was quieted for many days by man-made drugs, which offer his ailing heart a rest, Sharon became her strong husband’s voice. She also became the voice for the 70-plus family and friends who wait for the daily e-mail updates. These have become a cathartic release after long days of hospital time wedged with family and work. Electronically, she shares good and bad news while learning the intricacies of communicating across a vast space.

April 11 - Just an FYI … AOL blocked my account last night because they thought I might be spamming people. I had to request formal permission to send out these e-mails as a Heart Transplant Newsletter. The things I’ve learned!!!!!! April 11 - Just an FYI … AOL blocked my account last night because they thought I might be spamming people. I had to request formal permission to send out these e-mails as a Heart Transplant Newsletter. The things I’ve learned!!!!!!

Steve is a local soccer coach and avid fan. In January, the youth soccer team he coaches became the first Maryland team to be invited to the National Indoor Soccer Championships in Indianapolis. For years before moving to Calvert County, he was an impetus behind the growing youth sports program in the Marlboro Boys and Girls Club of Prince George’s County, where Philip and Bethany learned soccer under dad’s guidance. He has been the life blood of this youth program. Now he waits for his life blood.

The Blood of Life

“Steve will do anything for anybody. He is the type of person who always gives,” says Steve’s best friend and co-teacher Barry Clark of the blood drive that brings friends and donors to Southern Middle School on May 21. “That is why we are doing this today, so other people have the chance to give the gift of life.”

Barry and Steve grew up within miles of each other in southwestern Pennsylvania, but they did not meet until both became teachers at Southern Middle. Both teach technology education, and they each have a twin. Their love for one another is born of those connections and more. They have taught side-by-side for 24 years.

Steve is “doing better,” Barry says. A heart pump is keeping him alive, but he is “doing better.”

The blood drive has a festive feel like a community gathering. Students from years past mingle with co-workers, friends and neighbors. Many students have returned to donate blood on Mr. Ferralli’s behalf. For Gerald Lopez, a student at UMBC, “It is Mr. Ferralli. There could be no better reason,” for the wait of up to one and a half hours.

Former student and now co-worker Jenn Moore is here, she says, because “Steve is a good friend of mine.” She, too, is glad for the chance to help.

“The phones have rung off the hook,” with prospective donors says Mary Gardner, the school nurse who, along with Gerry Ward, the principal’s secretary, coordinated the drive with the Washington Hospital Center.

“There is a reservation list for the next drive.”

This drive being held in Steve’s honor will provide blood for other needy patients at Washington Hospital Center. The next drive could coincide with Steve’s transplant, with the blood going directly to him. Today it matters not who uses the blood. The spirit is borne of support and love.

Former neighbors Brent and Debbie Herr drove from Marlton in Prince George’s County. “It is the least we can do,” Debbie says.

Within this cafeteria at a local school, folks give of themselves for one of their own. The students, their parents, co-workers - whether past or current - mill about as they wait their turn. First there’s intake at one table. Next, the medical check: iron levels, blood pressure and very personal questions. Then there is the wait to give blood. After a pint of blood has flowed from their arm, donors are encouraged to take a snack, lemonade and cookies. For those who find themselves light-headed, there are cold compresses and juices to replenish the pint taken.

The staff from Washington Hospital Center works efficiently, almost as an aside to the gathering. They ask the questions and keep the donor lines moving. “It is good to have donors,” says Patricia Beckham, who worked as a shock trauma nurse for many years.

April 14 - We’re still hoping a heart becomes available in the next few weeks while Steve is at the top of the list. Even with all the good news, he really does need it. Please keep Steve in your prayers. Next week is National Organ Donor Week, and if you see anyone with a green ribbon on you’ll know what it stands for.

Even scarcer than pints of blood are organs for transplant. Gardner, who works with medical situations everyday, believes “fear and ignorance” of the need for donors keep the numbers low. She wishes more people knew about the need for organs and donors and that more people knew about the plight of Steve and others like him awaiting an organ for transplant. Should you become ill or have an accident, she says, organ donation is the last thing on anybody’s mind. The hospital’s number one priority is to save your life.

At a table in the back of the cafeteria is a group of teens in matching green shirts. They represent the soccer team that played in the Indiana tournament. Today they are sponsoring the organ donor sign-ups. They welcome people to their table, answering questions and showing sociability beyond their years. They have been touched by Steve Ferralli and they are touching back.

Team member and son Phil Ferralli, says, “the best way to provide this service was to coordinate it with the blood drive.” He, too, speaks of the need to raise awareness about organ transplants, and in his own mature way acknowledges that, “this may not be the way to save my dad’s life, but it may save somebody else’s.”

In spite of the festive feeling, there is that sobering reality bringing this community together.

Ups and Downs

Steve Ferralli’s medical journey has been a long road of ups and downs.

On February 9, his good health was abruptly interrupted as his heart went into atrial fibrillation. Fibrillation is the loss of synchrony between the atria and the ventricles, resulting in a kind of electrical storm within the heart. A-Fib, as it’s called medically, is life threatening, increasing damage to the heart muscle as the storm grows worse.

For some time Steve had been feeling winded merely walking up the stairs at school, but, he says, “I really didn’t think anything of it.” That night in February he nearly passed out. Sharon called 911.

The emergency response was quick and thorough. His vitals registered normal, so he was given the choice of riding to the hospital then or following up on his own. Comforted by the reports of his vital signs, he chose to stay home. He was able to fall to sleep that night, but felt worn and “real tired” the following day.

Then, at Sharon’s urging he went to the Dunkirk Clinic, where an electrocardiogram showed problems. His heart rate was 190, much higher than the 60–100 normal resting range. Visits to Calvert Memorial Hospital and, over subsequent weeks, to a cardiologist revealed cardiomyopathy, an enlarged heart whose function had been reduced to a life-threatening state. In Steve’s case, perhaps the culprit was a viral attack on his heart sometime in the past.

Decorated with hundreds of cards, Room 12, Building 4NW, a long 40 miles from Steve’s home, is a happy space for a visit. It is filled with color and Steve’s smile greeting each visitor. Ironically, from the window of Room 12 you can gaze upon the copter pad where he was brought more than 10 weeks ago. On March 28, Steve was airlifted to the Washington Hospital Center from Calvert Memorial. Is the copter on the pad the one he was transported in?

“Is it the red one?”

He remembers the red helicopter and being moved to the gurney. That is the all he remembers until waking up many days later after four surgeries.

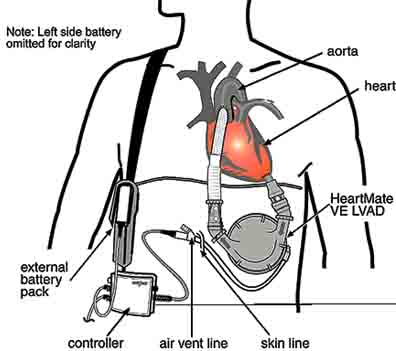

With the surgery of April 2 to insert both a right– and a left–vented Electric Ventricular Assist Device, RVAD and LVAD, Steve began a delicate passage. The days were marked by various procedures: insertion of a trach tube and a feeding tube; IV administration of numerous drugs to keep him in a restful state; and 24–hour monitoring in the Intensive Care Unit. On April 10, the RVAD was removed. It was the left side of his heart that was deficient. The right side could be controlled by medication only.

The LVAD that lies within Steve’s body is a round apparatus secured to his ribs just below the heart. His trainer, the Transplant Support Team member who teaches him to live with this LVAD, calls it the “canteen,” for that is how it looks. It is made of titanium and weighs three pounds. The LVAD that lies within Steve’s body is a round apparatus secured to his ribs just below the heart. His trainer, the Transplant Support Team member who teaches him to live with this LVAD, calls it the “canteen,” for that is how it looks. It is made of titanium and weighs three pounds.

From the canteen, flexible tubes are attached both to his heart and aorta. Blood is pumped from the heart first to it, then to the aorta. As air passes through the exchange valve connected by tubing to the outside of the body, the sound is a constant, even soothing, shoosh. Touch Steve’s left side, and you can feel the pumping mechanical heart from within.

For many days following these procedures, Steve was unable to speak. He was suspended in a quiet state induced by medications that allowed his body to rest, relax, and heal. He relives those days of trauma from the memories shared by family and friends who kept a vigil at his ICU bedside.

April 17 - What day is this??? Today marks 3 weeks in the hospital. It really doesn’t seem possible until I think of everything Steve has had done.

Heart pump illsutration courtesy of Thoratec Corp.

A Normal Day

Sharon arrives for her daily visit to Steve’s room and learns of today’s events: the long walk, the trouble stepping up just one step, the one-and-a half-hour heart pump review lesson. During this session, Steve is asked to consider what he would do if the electricity went off and his pump stopped. He will need to react with speed and intelligence. He will need to switch to batteries for back-up power. His trial run through these steps seems long as warning buzzers sound and both battery and wall cords look identical.

Reaching, grasping, plugging, he makes the change in long seconds, and the pump jumps back into action. He is preparing for the new life he will know at home with this pump sustaining his heart.

Time is framed by stories as voices drift around Room 12. Al Miller visits three or four times a week. “Steve has always been there for me.” He chuckles as he remembers Steve’s first words after five weeks of silence and writing notes:

Steve: “Hi.”

Al: “Oh, you can speak now?”

Steve: “You’re blocking the fan.”

We laugh at what seems a trivial exchange; yet the signs of the hardship and trauma that the Ferrallis endure are visible. The heart pump offers its continual shoosh, shoosh, the IV bags of medicine and nutrition hang nearby along with the machine to check blood pressure and vitals. A protein drink is delivered through a feeding tube, which snakes down Steve’s nose to nourish him. Each week he endures a barium swallow test. Each week he comes close to being able to eat food on his own. That eventuality will let him go home to a bit more normalcy.

The conversation drifts toward food. What’s the first thing he wants to eat? “The other day,” he says, “I wanted ribs. They had them on the Today show.” But now his appetite is non-existent. The high-protein liquid provides what he needs.

Amid the homemade posters proclaiming, “We Believe in Miracles” and “Hakuna Matata” (“Ain’t No Worries” from the Lion King), Sharon asks Steve about his heart flow rate for the day. It has been averaging five. This is a measure of volume pumped, with 4–7 being a good range. Sharon smiles radiantly and says, “Cardiology 101, I’m here.”

Each and every day is full of learning for these educators. Sharon’s ever-present strength fills the room with positive energy, leaving little space for any dark, brooding thoughts.

A Phone Call Away

In all the arduous process occupying the Ferrallis and the Transplant Support Team, locating a donor is the most difficult piece. It requires the tragedy of one to give new life to another. Heart transplants are now the third most common type of transplant in the U.S.; yet patients wait weeks and months.

The need for organs is daunting: In 2000, 22,854 patients received organs out of 76,400 waiting. Each day, 15 die, ending their wait for a healthy donor organ. “The need is growing larger than the supply,” says Ann Pashkey, the information specialist for the United Network for Organ Sharing. That Network, the link between donor and recipient, is a non-government, non-profit organization.

A healthy heart for transplant must come from a donor who is brain dead but on life-support. It must come from a person who has stated and written a request to be a donor; or from a family who has made that painstaking decision when their loved one is on life-support. (Learn more at www.unos.org.)

If you wish to be an organ donor, you must, Pashkey says, “tell your family. That is more important than signing the donor card.”

Organs are initially made available locally, then in concentric zones of 500, 1,000 and beyond 1,000 miles. One of the 60 nationwide organ procurement organizations arranges the recovery and transport.

When a match is made, the transplant center phones the waiting recipient. Within hours, the operation is underway. On May 18, the first heart transplant of 2001 was successfully completed at Washington Hospital Center. The recipient was not Steve Ferralli, but another fortunate individual who had the correct blood and tissue match. His wait - only since October - was relatively short. He returned home with his new heart a mere 10 days after the organ transplant.

A year earlier, on May 17, 2000, John Malloy of Gambrills had awakened at Washington Hospital Center to hear the words “Mr. Malloy, Mr. Malloy, You’ve got a new heart!” After a waiting of two and a half years, he calls his new heart “a miracle.”

“The wonderful thing about a heart transplant,” says Malloy of the miracle that transformed his life, “is that it is instantaneous.”

Waiting Your Turn

June 1 - Unfortunately, we learned today that Steve lost his 1A status. That means we are no longer at the top of the list. We understand that Steve is no longer critical, but he isn’t really stable either. As long as he has the IV drug, milrinone, supporting the right side it’s a concern. If an O+ heart becomes available tonight, Steve doesn’t get it … it goes to someone with O+ 1A status. We know our faith will be tested many times over … this may be one of those times.

In determining who will receive an organ transplant, a number of “matching” factors are considered. They include medical urgency, organ size, time spent waiting, blood type and genetic makeup. Each transplant hospital, of which there are over 200 in the U.S., selects the criteria for placing patients on the transplant list. Each patient is assigned a status code for his or her medical urgency. Status for transplant must be evaluated every 14 days. For all the successes Steve Ferralli has come to know mechanically, there is an ironic downside: He has lived 30 days with the LVAD — and done it so well that his status is downgraded.

It’s all a routine that really isn’t. When the phone call comes, Steve has told his doctor he “will be scared.”

Transport Support Team cardiologist Richard Cooke relates how tough the waiting is. He shares an analogy to the situation of a prisoner of war. For him, there is no time save the passing of each day. “The uncertainty eats away at people’s emotions,” says Cooke. He urges Steve to have faith and not grow discouraged. The job of the Transplant Team and the patient is, he says, “to make, on a day-to-day basis, the best operable candidate.” The love and continuing support of family, friends and medical staff are all working that way.

The statistics that Cooke shares with Steve include the positive news that 90 percent of transplant patients are alive after one year. Yet there is a 100 percent certainty of rejection. The statistics that Cooke shares with Steve include the positive news that 90 percent of transplant patients are alive after one year. Yet there is a 100 percent certainty of rejection.

The body will naturally try to reject any foreign protein substance, including a new heart. The key to survival is exacting use of the immunosuppressive drugs. These medications must be balanced in such a way as to prevent rejection yet not drop the body’s natural immunizing ability. How anyone’s immune system will respond is just one frightening unknown of the transplant process. Steve is astounded to learn that a younger person like himself has a higher chance of organ rejection. The immune system is stronger when we are younger.

When Steve’s turn comes, operating room players will work together in a now well established routine of fine surgical precision and sharp coordination that may take from six to 12 hours.

First his chest will be opened through the sternum. Then the pericardium, a fibrous sac that holds the heart, is cut open. This sac will be left open after the transplant; closing it would require too much additional time and subject the patient to other dangers. Tubes are attached to connect the aorta and the right and left vena cava to the heart–lung machine. Once the aorta and vena cavas are clamped off, the machine will work as both heart and lung.

As the damaged heart and the vessels are cut away, the donor heart, which has been carefully examined and made ready, is lowered into its new body. The left atrium of the patient’s heart is attached by sutures to the left atrium of the donor heart. Attaching the right atrium, patient and donor, is the next step. Once the pulmonary arteries are joined, the clamp on the aorta is removed. The flow of warm blood into the new heart should initiate heartbeat. If that heart beat does not begin or is unsteady, the support team will use defibrillation to effect about a steady, constant beat.

Once the heart is beating regularly, other vessels are unclamped, bringing full flow of blood to this heart. The heart–lung machine is disconnected only when the new heart is fully functioning and none of the hundreds of sutures is leaking. Finally, Steve’s chest will be closed.

With this new, life-saving heart in place, the patient will be monitored for 24 to 48 hours in the intensive care unit. Within three to four days, Steve Ferralli can expect to be up and walking.

New Dreams

April 29 - I think Steve was a bit sad about missing the big prom night. We took videos and photos and more photos.

“The hardest part,” says Steve with tears filling his eyes, “is missing the kids, the games and stuff.” Phil’s prom and Bethie’s activities are viewed by video, heard by voice. Those of us who share these moments with Steve and Sharon know the yearly trip to Disney World, with college visits planned along the way, is on hold. The week in Bethany Beach this summer will be missed. This active, fun-loving family will share a summer of hope and expectation of a different kind.

Steve’s brush with death has been rude, and he speaks repeatedly about his hope that his family and friends tune in to their bodies and get those medical checkups. He has experienced his own miracle; the fragility of life now surrounds every moment.

Steve’s dreams, he says, “are now. I live day to day.” This is a man who has touched death’s door. He speaks of no near-death experiences, yet he knows tenuous times. He speaks of living life more simply. He ponders briefly why it was he, a guy who does not smoke or drink, an active adult who worked at being physically fit. Yet he does not dwell on thoughts of what he calls “what-ifs and how-comes.”

Each and every day is about dealing with what you have. Steve Ferralli’s dreams are of leaving the hospital and getting back into a routine. “I can only look forward now,” he says. He will be taking life a little slower, giving up the weekend basketball game, being less physically active. When he returns to teach school in August, it may be with a heart pump. These are things he can live with.

June 6 - Please keep Steve in your prayers. The average wait for a heart transplant is 2 years. This could be a very long wait. Keep the faith … believe in miracles.

Steve and his family know that the journey ahead will be long and full of more challenges. Even with a transplant, he will endure months of physical rehabilitation. He will be on anti-rejection drugs the rest of his life.

These realities have not dampened his spirit, his faith. A rosary hanging over his bed was brought by a friend. Her daughter used it during some troubling times. It is a quiet reminder of the power of faith and prayer. Steve’s energy is tamed, but his love for and of life, family and friends is his spiritual nourishment. He is ever grateful for each new day.

“I wake up every morning and thank the Lord I’m alive.”

Copyright 2001

Bay Weekly

|