|

|

|

photo by Cristi Pasquella

Members of the cast, clockwise from top left, Jim Ballard, Tony Spencer, Zastro Simms, Chase Taylor, Kelvin Parker, Stephen Williams (kneeling), Torra Williams, Vivian Spencer and Stacie Williams. |

For Janice Hayes-Williams, History Is Among Us

by Martha Blume

God bless your house with Trustees … men of color … men of honor … to preserve our past while building a prosperous future for the generations to come.

Thus spoke the Reverend Henry Price in the flesh two hundred years ago at Asbury United Methodist Church in Annapolis. Psychologist-actor Jim Ballard repeated his ringing words last week on stage at Banneker Douglass Museum. As Price, Ballard opens the play Trustee, written by Annapolitan Janice Hayes-Williams and sponsored by the museum, its Friends and the Maryland Commission on African American Heritage and Culture.

In 19th century Annapolis, Price rose up out of slavery as advocate, benefactor, enabler — in a word, trustee — to a community of African Americans striving to make a society for themselves in a hostile, foreign land. His story — and the legends of three other men — so captivated Janice Hayes-Williams that she brought them back to life to inspire a new century.

Trustee is a work of love and self-discovery, not only for Hayes-Williams but also for the actors who play the parts and all who helped and watched the drama unfold. In it, too, are surprises, history lessons to be learned and in the end an unspoken challenge.

“I want people to know there was an African American presence here,” said Hayes-Williams, whose love for community history has evolved into her second career as an interpretive historian. “I want black males and other young people to see who took care of this community and pass it on down.”

On a Mission

Born in Annapolis, Hayes-Williams grew up in close touch with her grandmother, who often hosted social teas in her back yard on South Street. Hidden in plain sight, that high African American society of the early and mid-1900s was a whirl of teas, balls, weddings and opera.

“This was blowing my mind,” said Hayes-Williams at her discovery of reports in the Afro-American Ledger, predecessor to the current Afro-American, published in Baltimore. “Who cared in the Capital or the Post about our social activities; they would only report national news of African Americans, like lynchings.”

On leave from her Beltway job after illness, Hayes-Williams began digging in her dimly remembered past.

“I called my mother. I started going to cemeteries and recording death dates. I got into the history of Asbury United Methodist Church,” she recalls. “And I met Joan Scurlock.”

Trustee is dedicated to Scurlock, who died of cancer last year at age 58. At the Charles Carroll House on Duke of Gloucester Street, Scurlock had done extensive research on African American history. Teaming up, the two women found that together they had assembled many of the pieces of the black history of Annapolis in the 18th and 19th centuries.

As well as Scurlock, Hayes-Williams dedicates Trustee to two other historians who promoted her research: Phebe Jacobsen, director of reference services at the Maryland State Archives, who died in 2000, and Jack Kelbaugh, a collector of African American history who died in 2001.

“Phebe showed me how to use the archives, where I should look so as not to waste my time. Jack would send me bits of paper. Some of it was hilarious. It was much more than I could have accumulated on my own,” said the grateful pupil.

As the guardian of all this information, Hayes-Williams felt challenged to put it in a medium that would touch a wide audience. “Both my mother and my father were schoolteachers. My mother and grandmother wrote plays for the church. Writing is in my genes. I refused to be a schoolteacher, but I’m back in that venue, educating people about Annapolis.”

Thus Trustee took form and substance.

|

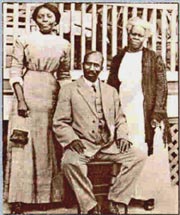

| Wiley Bates with his first wife, Maggie, and mother. |

In History We Find Ourselves

In the life of her play, Hayes-Williams also found herself. Among her trustees is Wiley H. Bates, her own great-uncle. “Bates has been a portal to my own family history, so, of course, he is my favorite,” she said.

Born a slave in Wageburrough, North Carolina (the site for the filming of The Color Purple), Bates and his mother moved to Annapolis following emancipation. From selling crabs and oysters on the streets of Annapolis, Bates reached out to help other African Americans start businesses and accumulate wealth, applying it to advance the Negro position and to please God.

It is not with egotism that I boast on some of my accomplishment but it is to educate others what can be attained with pluck and perseverance. We as Negros in this country must understand that the opportunities for forging ahead are as great now as ever and I might say, greater; but first of all, let God direct you.

—The Researches, Sayings and Life of

Wiley H. Bates, 1928

Pursuing Bates’ history, Hayes-Williams found herself in her grandmother’s parlor. For this self-made man married Maggie King, Hayes-Williams’ great-aunt. Hayes-Williams’ mother told stories of Bates’ calls to her grandmother’s home. The parlor furniture where the families visited now sets the stage for Trustee.

The familiar setting reminds Hayes-Williams of a story her mother likes to tell. She and her sister got new baby dolls, black dolls to replace their white ones, from Bates, who wanted them to be proud of who they were, not to emulate whites.

Bates’ wife Maggie died of a cerebral hemorrhage only eight years into their marriage. Her younger sister, Annie King, became the second Mrs. Bates.

Actress Torra Williams portrays Annie King Bates. In a decade of acting, Williams has worked with The Colonial Players, at the Charles Carroll House and in Colored Girls who Considered Suicide when the Rainbow is Enuff at St. Philip’s Church. In addition to several commercials, her film credits include work as an extra in Minority Reports, with Tom Cruise, directed by Stephen Spielberg, filmed in D.C. and Georgetown and due to open this summer.

Williams was born and raised in Annapolis, but Trustee has opened her eyes. She hadn’t known, for example, that blacks owned property and many businesses. “These blacks provided stepping stones for future blacks from my generation,” she said. “I am thankful to Janice for keeping this history alive.”

The history trail led Hayes-Williams further back still, to her great-grandfather, William Henry Hebron.

“Bates nominated my great-grandfather, who was a fish merchant, to be market master, which is synonymous with harbor master. Bates’ vote was the only one he got,” she laughs. Both men were trustees of Asbury United Methodist Church at the same time, Bates becoming a member in 1889.

Portraying a young Bates, actor Chase Taylor, 17, said he had “big shoes to fill.” An actor since eighth grade, Taylor steps out of his recent role in the Anne Arundel Community College opera Orpheus in the Underworld to play a man he calls “very ministerial, very preacher-like, very stern, but not so stern that you wouldn’t want to talk to him.”

And very prosperous. Bates’ store on Cathedral Street was reportedly the largest owned by an African American in Maryland. He purchased land for his own home on Cathedral and South streets, eventually achieving such success in dealing real estate that it became his full-time career in 1921.

For days on end I ponder the future of the Negro. There are not enough business enterprises among my people. The Negro must learn trades, and enter largely into business pursuits. … We the Negro must also understand that it is not the lack of wealth, but the application of wealth. To date we as a people have not learned how to apply it to our advantage.

—Bates in Trustee

Through education, Bates reached into the future he pondered. In 1899 he built a kindergarten at his home.

“Around 1927, my mom went there,” Hayes-Williams recounts.

In 1930, Bates bought land for the first African American high school in Anne Arundel County, later named Wiley H. Bates High School in his honor. Black students came from as far as the Baltimore City line in the north and Calvert County in the south to attend the school, which was more than a place to get an education. It was a community where African Americans learned self-respect and belonging. The grounds allowed for luxuries for blacks that whites took for granted — a gymnasium, science labs, a place for dances and band practice.

Bates High closed its doors in 1981, since falling into disrepair. But the spirit of Bates lingered behind the closed doors and was resurrected when Arundel Development Services broke ground in 1999 for its renovation into a home for low-income senior residents and a senior center. Hayes-Williams, who is historical consultant for the renewal project’s memorial to Wiley Bates, discovered that Bates’ hopes are being fulfilled long after his death in 1935. His will states his wishes for the establishment of the “Bates Old Peoples Home” for “old colored people regardless of sect.” His memory will linger in visible memorials to him throughout the halls of the home, which will house people of all races.

Knowledge to Pride

Through projects like the renovation of Bates High School, Hayes-Williams sees a renewed interest in the cultural history of Annapolis by people of all colors — interest lacking until recently. She said of her play,

"It’s for everybody, for all people. That’s important.”

Not least of all, it’s for her children, Stacie Williams, 12, and Stephen Williams, 14. Both are in the play. In Trustee, Stephen plays Kirk Whiteside, a young man who works for Marcellus Hall. Stacie portrays Sarah Price, granddaughter of Henry Price.

Because of their mother’s efforts to discover the past, her children are “entrenched in their history,” said Hayes-Williams. This is Stephen’s acting debut, though Stacie has played the slave girl Nellie at the Charles Carroll House. She also had a small part in her mother’s play, Four Women of Annapolis, last year.

“We learned a lot about our history by going with my mom to the archives,” said Stacie. “Sometimes she quizzes us,” she complains, “but she wants us to know what our ancestors have done.”

Hayes-Williams said her children’s experience has given them a sense of pride and dignity. “If you had asked me [as a young woman] to portray a slave girl,” she said, “I would have told you where to go.”

|

photo by Cristi Pasquella

Jim Ballard portrays Rev. Henry Price, who helped 19th century Annapolitans rise up out of slavery to make a society for themselves. He also established the first church in Annapolis solely for people of color, Asbury United Methodist Church on West Street. |

Justice For All

Where Wiley Bates sought opportunity for blacks, Henry Price sought justice. Born in 1792, a free man and a mulatto, he took neither of these facts of his heritage for granted. He married a mulatto slave, later purchasing her freedom. When race issues were more complicated than white versus black — when degrees of blackness mattered, too — Price established the first church in Annapolis that was solely for people of color, Asbury United Methodist Church on West Street.

Psychologist Jim Ballard plays Price. Ballard’s career has moved him from performing music to acting in opera — he, too, has just appeared in Orpheus in the Underworld — to producing plays. His productions have been both for private agencies and for his church, St. Philip’s Episcopal in Annapolis, where he coordinates “performing arts ministry,” including a Feb. 23 benefit for Sojourner Douglass College.

Ballard reaches out to Price across a chasm of time.

“It’s a way of thinking I can’t altogether relate to as a person,” said Ballard, who identifies with his character not on a personal level but by understanding that period of history and Price’s motivations. “If I let my motivations enter into it, I would have difficulty playing Price,” said the psychologist-actor of his conviction that religion should be inclusive, not divided into black church and white church.

In the early 1800s, free blacks — property owners or not — could not worship freely. All people of color were allocated to the balcony of the white people’s church. They took communion last and exited church by a side door. Black preachers could not administer the sacraments: baptism, communion, marriage or burial of the dead.

A rich inheritance and success as a merchant and dealer in real estate made Price a wealthy man. With his wealth, he manumitted many slaves and was trustee to minor children of his friends.

We own stores, taverns, pipe and tobacco shops, we are carpenters, blacksmiths, carters, wheelwrights and some of us use our profits to purchase the freedom of those held under the bounds of slavery.

— Henry Price in Trustee

In 1838, Price purchased land on Main Street for a church and petitioned the First Methodist Episcopal Church for permission to build a church for all people of color. A white pastor was assigned to serve Asbury United Methodist Church until Emancipation in 1864, the year Price died. Still, the black people had their church.

Hayes-Williams’ first play, written and directed by her in 2000, was A Church Divides, about the beginnings of Asbury. “It was a gift of love,” she said of the story of her own church. Her family is listed on its first records, dating back to 1832.

As well as a legacy of religious freedom, Henry Price passed on a tradition of personal achievement. His grandson, Daniel Hale Williams, performed the world’s first open-heart surgery in 1898.

|

| After serving in World War I, Marcellus Hall returned home to Annapolis where he became caretaker of Carvel Hall at the Naval Academy and used that position to give young black men employment and opportunity. |

Slavery to City Hall

Last year, Annapolis elected its first black woman to city council. In 1873, the city elected its first black man. That man, William Butler Sr., intrigued Hayes-Williams.

“I chose William Butler as one of my characters because his story has never been properly told,” she said of the first black alderman of the city of Annapolis. “The history was as significant when he was elected in 1873 as it was in the year 2001.”

Actor Tony Spencer of Annapolis found a common chord with the man he portrayed. Butler sought his part of the American dream at a time when many blacks were still coming up out of slavery. Spencer’s great-great-great grandfather, William Spencer, acquired his freedom during the Civil War and fought for the Union Army, eventually rising to Captain. He purchased over 18 acres of land, which he called Freetown, a haven for free blacks in Anne Arundel County. The town still exists, between Glen Burnie and Pasadena.

“My family has always told me, ‘You work for what you want and you get what you want’,” said Spencer.

So he could put himself in the shoes of the self-made Butler. Born a slave in Anne Arundel County, Butler got his freedom in 1846, just before his 21st birthday. He came to Annapolis, married Sarah Brown and followed the trade of his wife’s uncle, master carpenter Charles Shorter, who built Asbury Church and Reads Drug Store on Main Street.

As a carpenter and, later, real estate agent, Butler became rich. In 1863, he bought a luxurious 12-bedroom townhouse at 148 Duke of Gloucester Street, next to City Hall. He shared his wealth, providing land for the first colored Baptist Church in Annapolis. Later he built five frame row houses on Market Street as rental properties, providing a legacy to his children. Butler was a faithful member of Asbury Methodist Episcopal Church, trustee of the Stanton School for black children and a member of the Masonic Order.

I asked God to give me the moment of choosing, and I chose … we look after our community, our families, we raise funds for the church and for the poor. We all own property, pay taxes … For God’s sake! Don’t these responsibilities, responsibilities that we take as seriously as any man, regardless of race or color … afford us a voice in Government?

— William Butler in Trustee

Like his character, Spencer can boast a resume of achievements in service to family, church and community. An honor guard for President Richard M. Nixon, he worked for the Annapolis Fire Department for 23 years, then as a lecturer at the Maryland Fire and Rescue Institute and now in recruitment and equal employment opportunity for the city of Annapolis. He serves on the Anne Arundel County School Board, is a member of the Chamber of Commerce and chair of the Diversity Committee. He has acted with The Colonial Players and in other community theaters as well as in commercials.

Spencer’s wife, Dr. Vivian Gist Spencer, plays Butler’s wife Sarah. A professor of English, drama and

African American literature at Anne Arundel Community College, Gist Spencer said the character of Sarah differs from her previous portrayals of women of color in community theater and in presentations at the Charles Carroll House. “It’s my first time portraying a free black woman, an urban black woman, wealthy and politically connected.”

You Gotta Smile!

The final trustee who took the stage at Banneker Douglass last week was Marcellus Hall, trustee of young men. Working in the white world, Hall made his mark on black, white and naval Annapolis, earning the honorary title Admiral of the Chesapeake, given only by governors.

Born in Annapolis in 1894, Hall joined the army and served in World War I. Back home, he joined the U.S. Naval Academy as caretaker of Carvel Hall.

Carvel Hall, at Prince Georges and King George streets, defined the Navy’s social scene. In its heyday in the 1920s through 1950s, it offered rooms and entertainment for officers and their guests. And Hall was Carvel Hall’s presiding spirit.

Who, said Hayes-Williams, but Zastro Simms could bring Marcellus Hall to life? Her question was rhetorical, for the community activist had defined the role, however briefly, in Shipmates Forever, the movie that includes the story of Carvel Hall.

From Carvel Hall, trustee Hall brought in young black men off the streets, kept them out of trouble and gave them opportunity. Hall taught all “his boys” his winning ways.

Hayes-Williams’ son, Stephen Williams, and Kelvin Parker shined on the stage as two of Hall’s protegeés.

“My own father worked there, in the coat room, and my brother too,” remembered Hayes-Williams, who surprised her father, William Bates, and her grandmother, Elizabeth Cook, 90, on opening night with memories that brought their history back. “Do you remember Ms. Elizabeth Cook and her son? That Hayes boy whose shirts were always clean? His mother worked in the laundry all day.”

“You gotta smile when you do your job down here at Carvel Hall,” says Simms as Hall in Trustee.

Like his character, Simms said, “I love to entertain and to be entertained. And I tried to help a lot of young men in the community.” With then-mayor Roger ‘Pip’ Moyer, Simms walked the streets of Annapolis following the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., urging enraged citizens not to torch Annapolis. “Only one trash can got burned here,” Simms said of their success.

Moyer made Simms site supervisor of the Stanton Community Center. For “keeping kids too tired to get into trouble,” he was received twice at the White House, by presidents Nixon and Carter.

Simms and Hall have at least one more thing in common: Their lifelong dedication. Simms is as active as ever. As for Hall, when Carvel Hall closed, he guided walking tours for Naval Academy visitors until his death in 1971.

The Right Woman

Janice Hayes-Williams is walking in the footsteps of her city’s trustees. This May, with daughter Stacie, she inaugurates a new series of walking tours of Annapolis.

But first there is this month, this moment. “He who seizes the right moment is the right man,” said Wiley Bates one hundred years ago.

This moment Hayes-Williams has seized to revive the advice of the Reverend Henry Price, blessing her community of all colors and building its future by preserving its past.

God bless your house with Trustees … men of color … men of honor … to preserve our past while building a prosperous future for the generations to come.

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|