|

Juanita Foust uses a rain barrel connected to her downspout to capture rainwater. “We get six to eight barrels full per year,” she said. “A couple of years ago, we had a drought and that’s the only time it was empty.”

photos by Sonia Linebaugh

|

Barrels of Rain

Get ready for rain. You’ll need an umbrella and a rainbarrel or two. The umbrella

will help to keep you dry. The rainbarrel will help to keep your lawn and garden wet. Attached directly to your downspout, rainbarrels trap the water running off your roof and let you put it to use around your home. That’s your benefit.

“Rainwater is our lifeblood,” says Drew Koslow of South River Federation. “Yet we’ve warped the way it works. It’s become a major source of pollution for our streams and the Bay, carrying sediment and nutrients [like fertilizers and pesticides] from driveways and roads into storm drains. Rain barrels help put the water back into the ground slowly when used to water gardens and lawns.” That’s a benefit to us all.

Juanita and Cliff Foust of Fairhaven Cliffs like those benefits. For at least eight years, a rain barrel connected to the downspout of their home has kept their gardens flourishing. The Fousts use the water one bucket at a time on the flower beds, vegetables and potted plants that surround their cottage just a few hundred yards from the Bay.

“I thought we needed it for water conservation,” says Juanita Foust, “and it only made sense. We live on a well and it bothered me to have all the free water from the heavens going to waste. We get six to eight barrels full per year. A couple of years ago, we had a drought and that’s the only time it was empty.”

“Usually, we keep using the barrel, and it always has water,” says Cliff Foust. “We use a plastic watering can to dip out water for the gardens. Plastic is good because it floats while you’re filling it. Though the barrel’s hose broke and we lost the lid years ago, we are constantly dipping and the water never remains undisturbed long enough to breed mosquitoes. If water gets all the way to the top, the cats drink from it. In the winter, I empty it and turn it over.”

The South River Federation wants more homeowners like the Fousts. Working in partnership with Center for Watershed Protection, the Foundation — an association of 30 Bay area communities — has a plan and 100 rain barrels. Koslow will be giving away the barrels (two per family) and simple installation kits this Saturday. They are free to Foundation members ($30 family membership). A workshop explains their easy assembly and use.

Koslow’s enthusiasm over rain barrels is seconded by Steve Barry of Arlington Echo Outdoor Education Center in Millersville. “The idea is to take the speed and strength out of rainwater and filter sediment and nutrients out before they get to our rivers and Bay,” Barry says.

Arlington Echo made the barrels, purchased by the Foundation with a generous contribution from Bay Weekly and a grant from Chesapeake Bay Trust. “We get used soda barrels from Pepsi and Coke,” Darren Rickwood of the Center explains. “They arrive at the Center sticky and smelling of soda syrup.” Rickwood and the custodial staff clean the barrels, drill threaded holes for hose connections and add a strainer basket with fine net to filter out mosquitoes, roof gravel and leaves. They are constantly making innovations based on their observations of the 10 Echo Barrels in use at the Center.

On a day of steady rain, a pair of connected barrels goes from empty to full at a corner of the Center office. More barrels sit at another corner. Diffuser hoses carry the water to a nearby rain garden.

“A one-inch rain on a 1,000-square-foot roof yields 600 gallons of water,” says Rickwood, putting it in technical terms.

That’s a lot of water to pour down a storm drain. A lot of “free water from the heavens” that’s needed by our lawns and gardens, not by our waterways and Bay.

Get ready to benefit from summer rain. Get a rain barrel or two this Saturday at the South River Park Community building in Mayo (410/990-9173) or purchase barrels directly from Arlington Echo (410/990-0628). Learn more about rain barrels and other Bay water issues at www.stormwatercenter.net.

— Sonia Linebaugh

Harry the Heron’s Free Again — with a Little Help from His Friends

Harry the Heron’s Free Again — with a Little Help from His Friends

Ric Dahlgren’s lot in life isn’t glorious. As Annapolis’ harbor master, Dahlgren supervises two full-time, year-round employees. In summer he takes on a dozen or so part-time assistants to help maintain the city’s moorage facilities and to patrol the city’s waterways — looking not for pirates or smugglers, but for boats docked too close to private piers and bulkheads. And every day, one of Dahlgren’s assistants has to pilot the city’s pump-out boat — named for environmentally conscientious former state senator Gerald Winegrad — from holding tank to holding tank.

“I guess it isn’t too glamorous, having a pump-out boat named after you,” Deputy Harbor Master Dermott Hickey said. “So we just call it the Gerald W.”

John Risteff drew a long straw Wednesday, June 5, so he was in a patrol boat — rather than the inglorious Gerald W. — when Dahlgren radioed him from shore around noon. The crew of the schooner Woodwind had noticed a blue heron off Horn Point, struggling to keep its head above the water. Risteff set aside all thoughts of lunch and aimed the patrol boat toward the point.

He found the heron a few hundred yards from shore, a fish hook in its foot and its legs wrapped in line. It didn’t struggle when Risteff pulled it from the water, but instead flopped itself into the boat.

Dahlgren called Ted Kitzmiller, co-director of Noah’s Ark, a private, non-profit wildlife rehabilitation hospital. Kitzmiller asked volunteer Tina Lorentzen to meet Risteff at the patrol boat’s slip. Risteff handed the limp bird, whom he’d dubbed Harry, to Lorentzen. She rushed Harry to the Anne Arundel Veterinary Emergency Clinic.

By the time the vet had removed the hook and given Harry a shot of antibiotics, the bird had nearly recovered from his ordeal. Lorentzen drove Harry to the Naval Academy and watched him fly away from the sea wall.

Unfortunately, Harry may be back. This wasn’t the first time one of the Bay’s wild birds has been snared by human carelessness.

“We’ve rescued ospreys that’ve been hanging out of the nest on fishing line,” Kitzmiller said.

Nor was this the first time Dahlgren has responded to such an emergency.

“Ric is always willing to hold injured wildlife (usually ducks or herons) for us until we can come for the creature,” Lorentzen wrote in a letter to Mayor Ellen Moyer.

No, Ric Dahlgren’s lot isn’t glorious. But it can be satisfying.

— Brent Seabrook

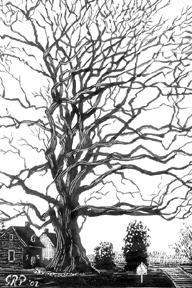

In Clones, Our Wye Oak Lives

In Clones, Our Wye Oak Lives

Thousands flocked to the site where the stately and majestic Wye oak had stood for well over four centuries to grieve the loss of the Maryland State Tree after it was blown to the ground by 60-mph winds. Tempering the grief, however, is the vitality of its progeny.

There are now 29 Wye oaks growing in Maryland soil, with two more growing in George Washington’s forest at Mount Vernon. With luck, several hundred more will be added to the list next spring when the newly grafted plants initiate growth.

Attempts at cloning the Wye oak started nearly 30 years ago, but in 1999, with the initiation of the Grand Champion Tree project, research was stepped up. For the Wye oak was also the largest white oak, Quercus alba, in the states and thus the Grand Champion White Oak. The objective of the Grand Champion Project is to clone as many grand champion trees as possible, because they are the largest and most likely the oldest trees of their species. By cloning these trees, we preserve the gene pool. Since the Wye oak was such a popular tree, it was the third grand champion to be successfully cloned. Had it not been for this project, the Maryland Legislature would have had to designate either a new tree or a new species in place of the Wye oak.

By using conventional grafting techniques, with certain modifications, buds taken from the branches of the Wye oak were grafted onto the stems of seedlings grown from acorns collected under the Wye oak.

The cloning of plants is not new. It was first described by both Plato and Aristotle as a means of growing superior figs and olives. In today’s world, all fruits grown for sale are cloned, as are some vegetables such as potatoes and sweet potatoes. Most shrubs and perennials used in landscaping are clones, as are many shade and flowering trees.

Cloning is accomplished using asexual or vegetative propagation techniques such as rooting stem cuttings, root cuttings, tissue culture, layering or grafting. The Wye oak was cloned using a modified grafting method because cuttings of oak trees do not root readily and tissue culture methods have not been successful with oak species.

Today’s Wye oak buds are grafted onto seedlings of the Wye oak. Thus all of the growth above ground is the true Wye oak. Someday, when the mysteries of tissue culturing or rooting of oak cuttings are discovered, it will be possible to grow Wye oaks that will be 100 percent true to genetic form.

Over the years, thousands of people have purchased seedlings of the Wye oak to plant in their yards here in Maryland and farther afield. To meet the renewed demand, the Maryland nursery industry is now likely to become involved in propagating and distributing Wye oaks.

There are many advantages to growing a Wye oak. We know that this tree has survived the test of time, 460 years. It has survived changes in the environment, withstanding diseases and insects common to oaks as well as road construction over its roots. For some 30 to 40 years, the old oak stood with a cavity in its trunk large enough to accommodate four grown men sitting cross legged around a card table. Yet its trunk supported 220 tons of branches and leaves against high winds, rain and snow

Yes, we will miss this grand old tree, but all is not lost.

— Francis R. Gouin: Professor Emeritus, University of Maryland

|

| photo by Daniel Gresham |

Chicago Invades Solomons

With song and light, Chicago ripped open the smooth June night spreading over Solomons at Calvert Marine Museum’s Waterside Music Festival on June 8. An old band played old tunes as fans revived old times, waving key-chain flashlights in time with the music.

“It was pretty neat,” said Bruce Wahl of Chesapeake Beach, a fan for the band’s 35-year life. “With the big brass, you get a bigger band sound than you usually hear with rock groups.”

He was not alone. Wife Becky limped in on crutches to rekindle old memories. Even their 18-year-old daughter, Megan Nestlerode, liked what she heard. The Wahls joined a sell-out crowd of 4,400 in raising organizer Lee Ann Wright’s expectations of record revenues to benefit the marine museum.

“We hope to equal the $61,000 we earned with James Brown last Labor Day, based on selling even more tickets,” said Wright. “And the bar’s doing fairly well. But we never know till we have our bills all in.”

Sponsors help the museum increase its profits, countering the high costs of paying for high-tech lighting and comfort stations. Highly visible for the first time at this Waterside Festival was sponsor, The Williams Co., on hand giving away the miniature green and lavender flashlights that lit up the audience. In Chesapeake Country, The Tulsa-based company is the subject of controversy as it seeks permits to reopen the Cove Point Liquified Natural Gas Dock on the Bay, above Solomons and below the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant.

“They wanted to convey to the rest of the community that they’re here and would like to work side by side with all of us,” said Wright.

Chicago, too, was celebrating some big numbers, traveling the East Coast in the band’s 35th anniversary tour. “After 35 years,” said saxaphonist Walt Parazaider, “we’re happy to be anywhere.”

They couldn’t have asked for a more beautiful anywhere to celebrate than Calvert Marine Museum. Venus rose first in the clear blue evening glow, and the stage lights came out second. Cheers chased away chills. Festivity, embodied in beachballs, sailed above the exuberant crowd, passing from moms to dads to the occasional under 20, adding up to a jovial explosion, ignited by such songs as “Hard to Say I’m Sorry/Get Away,” “You’re the Inspiration,” and “Will You Still Love Me.”

For fans too cramped by the closely crowded chairs, there was space to wander and food stands to patronize. Pizza and soda, crabcakes and beer, the energy in the air set this $35-a-ticket evening far above your average dinner-and-a-movie.

— Eric Smith and Sandra Martin

Way Downstream …

In Cecil County, the effort to add the 189-acre Garrett Island to the Susquehanna National Wildlife Refuge is coming up short. The Bush administration said last week it has no interest in buying the uninhabited island, despite the urging of Rep. Wayne Gilchrest. The island is left over from a volcano and has many Indian artifacts but none of the endangered species that could trigger federal purchase …

In St. Michaels, the family of Ed Graf, killed in the attack on the World Trade Center, last week dedicated a rowing skiff bearing Graf’s name at Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, the Star Democrat reported. Graf, a securities trader, was halfway done with the handmade boat when the tragedy hit …

Our Creature Feature comes from Virginia Beach, where Kate Mansfield of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science is spending many hours listening to Lee and Travelin’ Al. They are loggerhead sea turtles, not country music stars, and they’ve been nursed back to health and fitted with radio transmitters.

The project will enable researchers to learn habits of the threatened sea turtles and to see how they fare after being rehabilitated from serious injury. “It’s a behavioral thing and an environmental thing,” Mansfield told the Virginian-Pilot.