|

|

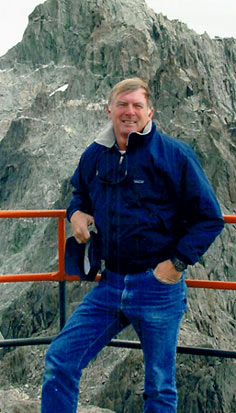

Memorial to a Missing Sailor

|

| Local sailor Tom Olchefske, lost at sea since last June. |

It’s been a year since Betsy Crozer’s 39-foot sloop, Tropicbird, was found on a reef off the southwestern shore of Antigua. Tom Olchefske, Crozer’s longtime companion, had vanished. He’d left Trinidad two weeks before, intent on sailing the boat home to Annapolis. His body was never recovered.

Olchefske was a capable mariner whose strength belied his age. At 60, he sailed with the same confidence that had helped him deliver the energy conservation and alternative energy industries through tumultuous births.

Outside of work, Olchefske’s interests were many and varied. He skied on snow in winter and water in summer. He played guitar and harmonica.

“He was an aficionado of classic automobiles,” Olchefske’s buddy, Mike Swift, wrote in a memorial for the Singles On Sailboats newsletter. “His last project was the restoration of a 1967 Ford Fairlane.”

More than anything, though, Olchefske loved to sail.

“His lifelong dream was to sail around the world,” Swift wrote.

Olchefske and Betsy Crozer met as two of the 1,000 local Singles On Sailboats. In 1992, she invited him aboard her boat for a two-week cruise to New England. They moved to Annapolis later that year, Olchefske from Silver Spring and Crozer from Delaware.

“After that, we were inseparable,” Crozer said.

They moved onto Tropicbird in 1998 and spent that summer sailing from Annapolis north to Maine and south to Bermuda. They spent three years sailing the Caribbean, resting up in Trinidad and the Windward Islands.

Then, in 2001, Crozer fell ill. Doctors told her she needed surgery, and she returned to Annapolis for the procedure. Olchefske decided to sail Tropicbird home to the Chesapeake, alone.

“Our home in Annapolis was rented,” Crozer said. “We needed the boat to live.”

Olchefske left on Thursday, June 7, He’d arranged to make regular radio contact with friends back in Trinidad, but he never made a call.

On Sunday, June 10, his friends called the U.S. Coast Guard, which sent out aircraft, checked with immigration and searched harbors up and down the coast of the Caribbean.

Tropicbird was found 10 days later. The Antiguan police seized the vessel, but their search uncovered no clues.

“Tom’s personal effects were on board,” Swift wrote, “but there was no sign of him. The sails were up, the wind steering was engaged and there were no signs of foul play. His last entry in his log was dated June 8, located 32 miles from St. Vincent. Tom is listed as lost at sea.”

Olchefske always told Crozer he wanted to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery, with full military honors. A decorated veteran, Olchefske joined the Navy after graduating from the University of Minnesota. He attended Officer Candidate School in 1966 and served in Vietnam and Panama before leaving active service in 1970.

Despite Olchefske’s service record, Crozer needs a certificate of death to fulfill his wish — a certificate only the Antiguan government can supply. Antigua’s laws are based on Britain’s, so a person must be missing for seven years before a death certificate can be issued. Crozer has hired an American lawyer to find a way through the law, but her hopes aren’t high; it took her until December to wrench Tropicbird from Antigua’s tight grasp.

Now the boat sits at Yacht Haven in Annapolis. At first, Crozer wanted to sell it; now she’s not sure. As much as she wants to move forward, lack of resolution prevents her from letting go of the past.

The Navy helped by arranging a memorial service for Olchefske at the Academy. Originally scheduled for September, the service was postponed after the terrorist attacks. Crozer rescheduled for October 29 — her birthday.

“I chose it so I wouldn’t have to be alone,” she said.

She wasn’t. Ninety-seven people turned out for Tom Olchefske’s memorial service, including his six siblings and two adult children.

Singles On Sailboats also helped Crozer inch toward resolution. On a sultry Thursday evening late in June, a year after Olchefske’s disappearance, SOS members packed the Boatyard Bar and Grill in Eastport, on the south side of Annapolis. They watched Crozer hand a triangle of worn yellow cloth to Dick Franyo, the Boatyard’s owner.

Franyo caters to the local sailing community. The Boatyard’s spotless white and maple interior is enlivened by dozens of small, colorful flags. Called burgees, these flags represent local yacht clubs and sailing fraternities.

To represent Singles On Sailboats, Betsy Crozer offered the burgee that had hung from Tropicbird’s mast. Franyo gave it a place of honor, above a plaque memorializing Tom Olchefske.

“I just asked if we could hang a burgee,” SOS member Ron Pence said, “and now he’s doing this.”

— Brent Seabrook

Last Word on Birds

4:35am. House sparrow sings from her home in the back end of the nearest street lamp. Chirup-cheerup-chirup. Day is begun. 4:35am. House sparrow sings from her home in the back end of the nearest street lamp. Chirup-cheerup-chirup. Day is begun.

Back in February, the fifth annual Great Backyard Bird Count focused citizen scientists on 20 and more kinds of sparrows and fellow birds at feeders, in neighborhoods, along beaches, in the woods and over the snows. In March, we added our sightings of 582 birds to Maryland’s 102,878 reported in the same four-day period.

Now, Count sponsors Frank Gill of Audubon and John W. Fitzpatrick of Cornell Lab of Ornithology bring us their thanks and a final update. “This year,” they write, “we received over 47,000 checklists from tens of thousands of citizen scientists.” Rare sightings included a powerful Asian bird, the gyrfalcon, in Massachusetts; a great spotted woodpecker visiting Alaska from Asia; and the first reported broad-billed hummingbird in Georgia.

“More importantly,” say Gill and Fitzpatrick, “participants helped document the ranges of common winter species like dark-eyed juncos, black-capped chickadees, mourning doves and spotted towhees.”

Owls, in particular the great snowy owl made familiar as Harry Potter’s messenger bird Hedwig, were the emphasis of this year’s count. From their homes in the northern part of the continent, these powerful hunters wing great distances in search of prey. They were reported in 20 American states and Canadian provinces, coming as close as Virginia but not letting themselves be seen by any Maryland observers.

Eurasian collared doves were also absent from the Maryland count, but they are on the move. They arrived in Florida in the 1980s and have steadily expanded their range, generally northwest, making the count in 21 states this year. Their impact on native populations like the mourning dove — whose coo-coo wafts softly along local hedgerows and fences — is under observation. Eurasian collared doves were also absent from the Maryland count, but they are on the move. They arrived in Florida in the 1980s and have steadily expanded their range, generally northwest, making the count in 21 states this year. Their impact on native populations like the mourning dove — whose coo-coo wafts softly along local hedgerows and fences — is under observation.

For the second year, Anne Arundel County’s Lothian was first on Maryland’s list of top-10 counting locations. This year, Lothian’s total was 75 species, 14 more than last year. Nationwide 4,727,536 birds were counted in 505 species.

Light wanes. A message sounds from the telephone wire. KrrDEE-krrDEE-krrDEE chirUP-cheerUP-chirUP. The northern mockingbird has the last word.

For more Great Backyard Bird Count results go to http://www.birdsource.org/gbbc/results.htm. For information about a five-year statewide study to update The Breeding Bird Atlas of Maryland and the District of Columbia check out www.mdbirds.org • 301/855-2848.

— Sonia Linebaugh

Bay Skipjacks a National Treasure

For over 100 years, the wooden sailing vessels called skipjacks followed the call of autumn. The beloved Bay craft — which grew to a fleet of nearly 1,000 — was said to skip across the water as it dredged the Bay for oysters throughout the winter in months spelled with the letter R.

|

Capt. Wade Murphy explains oyster dredging on sightseeing tours aboard his skipjack Rebecca T. Ruark.

photo by M.L. Faunce

|

Today, only a dozen or so vessels remain. The skipjacks and the hardy watermen who worked them have declined with the oysters they harvested.

Now, the last commercial sailing fleet in the United States has been added to the 2002 list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

“In many ways, the skipjacks symbolize the Chesapeake Bay,” said National Trust president Richard Moe — a part-time Calvert Countian — in making the announcement.

Since 1988, the Trust has designated some 120 threatened one-of-a-kind historic treasures, from urban districts and rural landscapes to Native American landmarks and 20th century sports areas. While the listing doesn’t ensure the protection of a site or guarantee funding, the designation can be, say the Trust’s preservationists, a “powerful tool for raising awareness and raising resources to save endangered sites from every region.”

It took the sinking of the fleet’s oldest skipjack, the 100-year-old Rebecca T. Ruark, to sound a distress signal loud enough to be heard round the Bay and to the State House.

[Visit Bay Weekly online at www.bayweekly.com for archived stories “Rebecca T. Ruark Rises”: Vol. VII No. 47; “Dock Update: From Rebecca Ruark’s Mast”: Vol. VIII No. 8; and “Preserving Maryland’s Patrimony”: Vol. VIII, No. 24.]

Maryland Gov. Parris Glendening stepped in and set up Save Our Skipjacks, a task force that, to no waterman’s surprise, found the remaining vessels “severely deteriorated, threatened by the elements” even as the Bay’s oyster population plummeted to all-time lows under ravages of the ominous sounding diseases dermo and MSX.

The old boats demand costly and painstaking hours of hand work each season. Compounding the fleet’s woes, owners couldn’t afford to insure or maintain the wooden boats, and skipjack by skipjack they disappeared. Even if they endured, what job would these workboats do in our almost oysterless era?

Task force findings and greater awareness lead to the Skipjack Restoration Project and a shipwright apprentice program at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels. When the task force further called for “alternative but compatible use of the commercial vessels,” and oyster stocks plummeted to all-time lows, resilient skipjack captains like Wade Murphy and Ed Farley became teachers.

Captain Ed Farley once mortgaged his home to make repairs to the H.M. Krentz, launched in 1955 as one of the newer vessels built for the rigors of Maryland’s winter oyster dredging. The beamy open deck so apt for oyster dredging is the “perfect setting for social gatherings and makes a great outdoor classroom,” says Farley, who worked with James Mitchener when he was researching his novel Chesapeake. Farley also developed skipjack environmental education for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

Rebecca Ruark Captain Wade Murphy, the only third-generation skipjack captain, has nearly 50 years of oyster “drudging” behind him. “I’ll go anywhere,” says Murphy, a one-man band when it comes to educating folks about the skipjack. Besides cruises, he’ll arrange “marryings and buryings” from the Rebecca — though for the latter he says “you’ll have to get the okay from the Coast Guard to spread the ashes.”

Enrollment on the list of Most Endangered Historic Places may keep our remaining skipjacks from settling down into Davy Jones’ locker. “This is the last chance for the commercial skipjack fleet and the continuation of a century-old way of life,” said Moe.

Take a sail on a historic treasure — help hoist the sails, throw out a line — spring through fall, when oysters are out of season.

- Rebecca T. Ruark with Captain Wade Murphy. Two-hour sightseeing cruises with oyster-dredging demo from Tilghman Island’s Dogwood Harbor. $30 per person: 410/829-3976 • www.skipjack.org.

- H.M. Krentz with Captain Ed Farley. Two-hour working or sightseeing cruises with up to 32 passengers from Tilghman Island’s Dogwood Harbor. $30 per person. Crab feasts and other ports by arrangement: 410/745-6080 • www.oystercatcher.com.

- Nellie Byrd, a 56-foot skipjack built in 1911. Two-hour tours and oyster dredging demonstrations up the Chester River with Captain Michael Hayden. $30 per person from Chesapeake Bay Exploration Center, Kent Narrows: 410/299-4540.

- Nathan of Dorchester, a traditional skipjack commissioned in 1994 and funded and built by volunteers under the direction of Bobby Ruark. Charters up to 28 people for two-hour summer sails from Cambridge: 410/228-7141 • www.skipjack-nathan.org.

— M.L. Faunce

From Annapolis, A Journal of the Arts

|

| BrickStreet editors Corey Sebastian, left, and Megan Smith. |

“Inspiration nips at your heels when it wants to and not when you want it to,” says Megan Smith. And so it was that, just over a year ago, Annapolitas Smith and Corey Sebastian began their journey as editors of the new literary magazine, BrickStreet: A Journal of the Arts.

A year ago March, Sebastian answered a call from friend Peter Heyrman, the owner and publisher of Bear Press. Would she help him revive The Annapolis Anthology, a review that had showcased local work in the 1980s?

“At first I was intimidated,” explains Sebastian. “I’d never done anything like this before.” But with another longtime friend, Megan Smith, she rose to the project. Both had been longing to collaborate on a creative project.

Initially, say Smith, “Our sights were small, our premise simple: Assemble a magazine featuring the writings and artwork of Annapolis residents, or those who have close ties to the town. Distribute it locally. Repeat if desired.”

They solicited donations; put out calls to local artists and writers; and designed business cards, graphics and layouts.

Along the way, the project’s scope and geography grew. Submissions appeared from around the country: Texas, Washington State, New Jersey, New York. Even Australia. There was still plenty of local flavor in the offerings coming in. But what was evolving was more than a local — or literary — magazine.

As they reviewed photography and illustrations and received pieces from local artists and musicians describing their creative process, they recognized they had a journal of the arts on their hands. The first issue’s theme is the creative process.

As they brainstormed a title for their new publication, they considered, Sebastian says, “following the custom of so many journals, and naming this one by its geography.” They found precedent in Gettysburg Review, or the local Potomac Review.

They wanted to reflect the magazine’s Annapolis roots but not to limit it.

“We used to joke about how ‘we’re takin’ it global,’” Smith says. So they settled on a reference to historic Annapolis’ brick streets.

If not global, Sebastian and Smith have gone national. The 128-page volume contains essays, poetry, stories, and artwork from writers, artists and musicians hailing from the Bay area and well beyond: Philadelphia, New York, New Jersey, Seattle — and Annapolis, Columbia, Baltimore and Glen Burnie.

The journal has meant lots of late nights and lost sleep. But there have been rewards. “We’re both so in love with it,” says Smith, “that even the most mundane tasks are a joy.”

Sebastian agrees: “We’re both so passionate about what we’re doing that it’s been worth all the sacrifices and time.”

The result is a monument to perseverance: to the tenacity of BrickStreet’s two editors and to the risk that contributors took in submitting pieces to a brand-new journal that might reject their work — or that might never come about.

All celebrated together in a June publication party at Annapolis coffee bar 49 West that seemed to embody the new journal’s spirit: to exact high standards on a shoe-string budget; to bring people together to share an artistic vision; to find joy and laughter along the way.

Information? www.brickstreetjournal.com.

— April Falcon Doss

Way Downstream …

On the Eastern Shore, there was cheering recently when the skipjack fleet was added by the National Trust for Historic Preservation to its list of America’s Most Endangered Historic Places. The designation can help raise awareness — and money — to combat threats to the stately, single-masted sailing vessels …

In California, a health advocacy group has declared war on what it regards as a public menace: the French fry. Environmental Health Watch wants health warnings accompanying America’s favorite potato dish now that a study in Sweden has found that a substance in chips and fries — acrylamide — causes cancer in lab animals. The World Health Organization said last week that there is a cause for concern but that more research is needed …

In South Africa’s Kruger National Park, patrols armed with machetes and chemical weapons fanned out last week in hopes of vanquishing a dangerous invader: the prickly pear plant. They are being targeted for their voracious thirst, sucking far more than their share of moisture from the soil in this semi-arid land … In South Africa’s Kruger National Park, patrols armed with machetes and chemical weapons fanned out last week in hopes of vanquishing a dangerous invader: the prickly pear plant. They are being targeted for their voracious thirst, sucking far more than their share of moisture from the soil in this semi-arid land …

Our Creature Feature comes from the Bay Journal, which offers a primer this month on the brown pelican now that it is returning to our part of the Chesapeake after being all but wiped out by DDT. The Journal tells us, for instance, that pelicans rapidly shed all of their feathers when molting, making it impossible for them to fly until the feathers grow back.

Pelicans are virtually silent, although their noisy chicks grunt loudly and even scream. And yes, it’s true what they say about a pelican: That its beak can hold more than its belly can — about three gallons of water.

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|