|

|

|

| photo by Romi Plociennik |

Will Maryland Crab Houses Slide into History?

by M.L. Faunce

Today: On the Edge

“It’s not a pretty picture,” says Jack Brooks, owner of J.M. Clayton Company, the oldest working crab house on the Eastern Shore, founded in Cambridge in 1890.

The picture worrying him is the future of the industry that’s both his heritage and a mainstay of

Maryland’s economy.

For four centuries, Chesapeake Bay created jobs and products for an industry that defined the culture of Maryland’s shore communities. Each of the five generations of Brooks’ family has had to grapple with outside forces that threatened the industry. For the last few years, the biggest threat was cheaper foreign crabmeat flooding the market. Imported crabmeat now accounts for two of every three pounds sold in the United States.

Now, says Brooks, regulations aimed to reduce the Chesapeake Bay blue crab harvest by 15 percent are “unfairly targeting” the business.

“It’s environmentalism in its extreme,” adds J.C. Tolley of Meredith and Meredith Company in Toddville, who, since 1963, has operated the lower Dorchester County picking house founded in 1920 by two cousins.

Following the second-worst harvest on record last year — some 20.5 million pounds — Maryland regulators banned the possession and importation of egg-bearing females. Saving those sponge crabs, they reasoned, gives billions of eggs a chance to replenish the distressed fishery. The regulations went into effect April 1.

|

| photo by Kelly Feltault |

The Catch

Maryland watermen, particularly trotliners, have been catching good, high-quality crabs, Noreen Eberly, director of Maryland’s seafood marketing program told Bay Weekly.

“With good, warm weather and no storms, crabbing should pick up,” she says.

Still, the 2002 harvest is not expected to set any records — at least not good records.

“We expect the harvest to be the same or a little bit better than last year,” said Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ John Surrick. It’s too early for confidence, but the prediction is 20 to 25 million pounds, which Surrick calls “significantly below the eight-year average of 31.5 million pounds.”

The larger crabs in that harvest go to the “basket trade” — to restaurants and consumers who want whole, live crabs, satisfying “the strong demand for beer and crabs,” according to Virginia Jenkins of Cambridge, scholar in residence at Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, who is writing a history of the seafood industry of the Chesapeake Bay from 1834.

Smaller crabs traditionally go to the crabmeat processing industry. Picking houses like J.M. Clayton Company buy up the females — including sponge crabs — and mixed-size males. At the picking houses, the crabs are steamed and picked, another threatened trade. Then crabmeat is packed, refrigerated and sent to market.

|

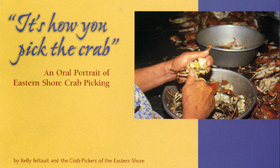

| In “It’s how you pick the crab,” folklorist Kelly Feltault, with the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, records the memories of Chesapeake Bay’s dwindling crab pickers. |

Caught

It’s not too early for crab-picking houses to assess the damage their businesses are suffering from the new regulations. Prohibiting the importation of egg-bearing female crabs has cut about 80 percent of their business, they claim. Some two-thirds of crabs picked in summer — when local demand for large, male steaming crabs is highest — have traditionally been females, brought in from other less-restrictive states.

Now those crabs are off limits in Maryland. But Virginia and North Carolina continue to harvest and process sponge crabs for sale in Maryland as crabmeat.

Against such odds, Maryland picking plants say they can’t compete.

Sales are off and demand is “soft” in Maryland, picking-house owner Brooks explains. “Their costs are cheaper, and their regulations are less restrictive,” he says.

More frustrating, he laments, is that “there are a lot of crabs out there. The supply of crabs is adequate, so it’s especially hard to take because it’s impossible to compete.”

Tolley makes the same complaint.

“Maryland processors have to pay more than twice what Virginia and North Carolina processors pay for crabs,” he says. “We’re lucky we have people who want to buy Maryland crab meat.”

April and May were hard, but in June and July, Tolley says that he’s been blessed with a reasonable supply of crabs. Still, Maryland crab meat processors pay about $22 a bushel for mixed crabs, while in Virginia and North Carolina processors pay $8 to $10 a bushel.

“We’ve gotten it on both sides, from the resource restrictions to the flood of cheap imports,” he laments.

On August 1, when Maryland regulations increasing the minimum legal size of hard crabs from five to five and one-quarter inches take effect, picking houses expect the other shoe to drop. Prices will certainly increase when those regulations kick in, predicts Larry Simns, president of the Maryland Watermen’s Association.

|

photo by Romi Plociennik

Jack Brooks, owner of J.M. Clayton Company, the oldest working crab house on the Eastern Shore, has had to let go one-third of last year’s workers due to hardships in the crab picking industry. |

Picking’s Last Stand

“Crabs are a way of life on the Eastern Shore, and the decline of the crab population leaves watermen, pickers and whole communities at risk,” says Shelly Drummond, of Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.

Five years ago, Maryland had about 50 picking houses.

At last count, 30 licensed crab houses were picking in Maryland. Almost all are on the Eastern shore, with 21 in Dorchester County alone. With the closing of Warren Denton Seafood on Broomes Island early this year, only one picking house survives on the Western Shore. That’s

Thompson’s Seafood at Colton’s Point in St. Mary’s County.

New regulations have hit Dorchester County particularly hard, says Brooks, whose picking house operated on a half-workday schedule this spring and early summer while Virginia plants worked six and seven days a week.

Two years ago, 40 people were employed by J.M. Clayton. This season, Brooks has downsized his operation by a third. That means a third less local pickers have work, he says, and those are people who may be one of several generations in the same picking family.

At Toddville, Tolley is proud of his workforce of “100 percent American crabpickers,” but their numbers are “slimmed down” from competition with foreign crabmeat.

Unemployment on the Eastern Shore is about 11 percent, seemingly bearing out Eberly’s prediction this spring that “the crab meat industry is going to bear the biggest brunt of the problem.”

That prediction was seconded by a University of Maryland Sea Grant Program study early this spring. Researcher Doug Lipton concluded that the new regulations would result in nearly $14 million in losses for the state’s picking houses. Hundreds of jobs would be lost and picking houses would be forced to close.

State regulators ignored that warning, processors say.

As Brooks ponders the “bummer this early season has been,” he worries what the future will bring for his son Clay, the fifth generation in his family to work in the crab-processing business.

He wonders aloud if a sign of the future may lie just next door to his picking plant. There, on three acres recently purchased by a Washington, D.C., developer, 50 to 75 condos will soon rise eight stories above the flat shore of the Choptank River.

He wonders, too, what the new condo owners will think on a hot summer day with a southerly prevailing wind, when the scent of crabs steaming and shell waste wafts across the creek. He already knows new folks don’t think much of the mosquitoes down there.

Processors say that their problem is compounded by the glut of cheaper foreign crab meat imported from around the world — Asia, South America, Indonesia, China and Turkey to name a few competitors. Brooks and Tolley agree regulations are needed to conserve the crab industry near and dear to their hearts, but, they stress, regulations should be “Bay-wide.”

“We’ve gone to Annapolis and argued our point,” says Brooks, meaning the blow to Dorchester and Somerset counties. “But it’s all political.”

Meanwhile, some 500 jobs in the crab picking business have been lost on the Eastern Shore. And that other shoe will drop next week, traditionally a time when crabs are running strong and pickers earn their best money working long hours.

On the day of the annual J. Millard Tawes Clam and Crab Bake, J.M. Clayton pickers were busy tackling 200 bushels of just-steamed crabs. “We should be at 250 or 300 bushels this time of year,” Brooks said.

What he would like to have told politicians campaigning at the feast was this:

“Let us stay in business. Like a lot of processors, we’re an old family business with several generations of workers. All we want to do is work.”

|

photo courtesy of Blue Ridge Heritage Archive; from “It’s how you pick the crab”

For generations, crab picking was mostly women’s work, paid “by the piece” or pound, and exempt from the minimum wage laws well into the 1960s. |

Yesterday: Already History

As Jack Brooks sees pictures of the future, Kelly Feltault hears voices of the past.

Not to worry. She’s a folklorist and oral historian, and the voices ringing in her head are those of what may be the last generation of Chesapeake Bay’s crab factory workers.

Since 1998, Feltault has recorded some 50 oral histories for The Center for Chesapeake Studies at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum at St. Michaels. The project began to bring the voices and the people of the Bay into the museum’s exhibits. It continued with funding by the Maryland National Trust and the Maryland Humanities Council.

Feltault calls her project a “folk documentation” in celebration of an industry that shaped the culture of Bay County.

“There is no stronger connection between culture and environment here than that of the blue crab,” she writes in It’s how you pick the crab — an Oral Portrait of Eastern Shore Crab Picking by Kelly Feltault and the Crab Pickers of the Eastern Shore.

The 40-page book, published by the museum, explains how early crab houses managed without refrigeration. With pasteurization, crab could be shipped long distances in containers stacked with cakes of ice in huge barrels. Most of the early crab packing equipment for sealing and pasteurizing came from old tomato canning factories once plentiful on the Eastern Shore.

You’ll read about child labor laws (and the lack thereof), and of how Marylanders started one of the first seafood workers’ unions in the nation.

Back then, lives were segregated everywhere except in the picking rooms, where black and white worked side by side. It was mostly women’s work, paid “by the piece” or pound, and exempt from the minimum wage law until the 1960s. There were some men, as well as generations of youngsters, “who learned to pick right alongside their mother.”

“Picking was a family thing,” remembers Donald Cephas, claw-cracker at J.M. Clayton Co. in Cambridge.

“All the people that worked here when I started around age seven was family, and that was over 50 years ago. Most of ’em had six, seven to 12 kids, and everybody worked together.”

Crab picker Laurena Collemer, who now trains pickers for the job she did for over 45 years, says, “We didn’t have babysitters on Hoopers Island back then, so Mama would take us to the crab house — some people even brought their playpens in there.”

Today’s crab pickers on the Eastern Shore are increasingly Mexican women, here during the summer on federal “guest worker” visas. Often isolated and homesick, they earn money to support their families just as local women on the Eastern Shore did for decades when crab was king.

|

photo by Kelly Feltault

Eight-time crab picking champion Joyce Fitchet said that picking crabs, she “learned that you got to work for what you want.” |

Voices Raised in Song

“Crab houses rang with the sounds of breaking shells, knives banging against metal and the sound of women talking,” writes Feltault. But the sound she says most plant owners and passersby remember is the singing.

“Someone would just start up and everyone would join in,” remembered Alice Palmer, claw cracker and crab picker from St. Michaels. “Old spirituals like ‘Sweet Our Prayer,’ and ‘My Hope is Built’ — always something that would be with joy — very seldom sad, something to keep your motion with picking the crabs.

“It’s three verses to ‘My Hope Is Built,’ and we would grab the chorus and hold on to it for the longest time, we would sing it over and over and over,” Palmer said.

Roy Harrison, manager at Harrison and Jarboe Seafood where the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum now stands, remembers. “It was beautiful,” he said. “Mostly toward the end of the day is when they’d start to get tired and then they’d start to sing. And gorgeous. I wish I could have recorded some of that. It was the most beautiful music I ever heard.”

|

photo by M.L. Faunce

Huge steamers like this at J.M. Clayton Company cook up to 20 bushels of crabs at a time. |

Honest Work

Future crab pickers started out cracking claws first, and they learned a lot more than picking. They learned about responsibility.

“It’s made me realize that you got to work for what you want … and I have at times worked three jobs just to survive,“ says Joyce Fitchet, an eight-time crab-picking champion at the National Championship in St. Mary’s County.

The comment Feltault says she heard the most — after the factories being “like one big family” — is that “crab picking is an honest day’s work.”

“I’ll tell you something about the dignity of it,” says Christine Smith, crab picker at Smith Island Co-op. “I was a lab technician before moving to Smith Island, and when I said I would pick crabs, they sort of frowned on it. And I’m just as proud right now of my work as anybody else because it’s an honest living. It’s the only thing that I can do to make a living here, and I’m proud of my product and what we do.”

There’s an art to picking a crab, the pros say.

“Coordination is everything in picking a crab,” says Donald Cephas. “If you don’t have coordination, you can forget it.”

Joyce Fitchet never considered herself a fast picker, but after patterning herself after former coworker Margaret Lee, her speed picked up. “The highest I ever picked was 21 gallons — and five pounds equal a gallon,” Fitchet boasted.

Still, says 40-year crab picker Nellie Flowers, “It’s not the fastness of it; it’s how you pick the crab.”

Into History

Through Feltault’s interviews, Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum discovered that Tim Howard’s Maryland Crabmeat Company in Crisfield was going out of business. The museum salvaged the contents of the picking house, according to curator Pete Lesher.

With a shrinking industry and little demand for used equipment, the contents were purchased at scrap value. That included the marine Scotch boiler, the 10-foot-tall steamer, the can-sealing machine and some 15,000 unused cans. Much of that equipment had been used onsite for tomato canning in the early 1900s. Also salvaged were a dozen or so cooking baskets, some made in a design unique to Crisfield. Even the time clock came off the wall, along with the workers lockers.

When the doors closed and crab picking and packing ceased, Tim Howard’s plant was photographed for a half-life frozen in time.

Then only the structure was left, a cinder block building with cement floor, stripped of “representative examples” of a time gone by.

Some future day, the Maryland Crabmeat Company of Crisfield will be reconstructed just as it was when women picked and sang their way through mountains of blue crab shoveled onto a picking table. Except that it will be empty of pickers, crabs and song.

Is It Maryland Crab? Is It Maryland Crab?

You pay a premium for crabmeat.

This week, the highest grade, jumbo lump, is running from $21.95 a pound at Tyler Seafood in Chesapeake Beach to $30.99 a pound at Annapolis Seafood Market. For the smaller pieces labeled backfin crab, prices range from $16.95 to $22.99 a pound.

What are you getting for your money?

Crab certainly, and possibly blue crab. But is it Maryland blue crab — or even Chesapeake Bay blue crab?

You’ll have to read the label carefully to know.

A one-pound plastic container of J.M. Clayton Company’s Epicure brand crabmeat bought last week proclaims its contents in lots of ways, but you’ll have to look at the fine print to know it’s Maryland crab.

The J.M. Clayton Company’s imprint says the crab was picked in Cambridge. And this container did indeed hold the meat of blue crabs, which are a traditional delicacy. That fact its label announces in two places. What’s more, the backfin meat that made such a delectable crabcake was “Maryland Quality,” the lid says up front. And it’s licensed by the Maryland Department of Health.

But to be sure it’s Maryland caught, you’ll have to look further. That guarantee appears in small print with the producer’s address, just after the zip code. The legend MD113 means this is indeed Maryland meat (VA would indicate crabs caught in Virginia). The numbers 113 are Clayton’s license number with the Maryland Department of Health.

Maryland crab picking houses — but not J.M. Clayton — sometimes import relatives of the Atlantic blue crab from foreign nations to pick and package under their label. The country of origin must be marked on the package — but you might have to look closely to find it.

—Bay Weekly staff with Katie McLaughlin

Copyright 2002

Bay Weekly

|