|

|

My Second Chance

Sometimes it takes a third party to link you

to your children

by Aloysia Hamalainen

The call always comes when you least expect it. Morning carpool drive in heavy traffic. The cell phone bleats. I start my ‘don’t call me when I’m driving’ spiel, only my barn manager interrupts with “Tangier’s down. It’s bad. Come now.”

|

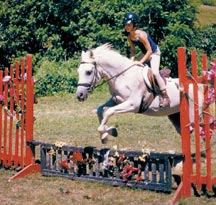

| When Elin, then 15, got on Tangier’s back, they connected like a plug going into a socket that turns on a lamp. |

I could not see for the moment, as my heart wailed, no, not again, I can’t take it again. Colic, easily the most dreaded word in the horse-owners’ worry list, had struck my family’s horse. Again.

In humans it can be merely a bellyache, but in the enormous intestines and bowels of a horse, an impaction or twist in the gut can quickly turn into a gruesome and tortuous death.

Miraculously, quietly, I answer, “Did you call the vet?”

As she replies, my eyes are blurry with tears, but I must stay calm. “I’m calling him now.”

“I’ll be there are soon as I drop these kids off,” I say lightly, thanking God my daughter Chrissy is home sick and does not have to endure this hell another time.

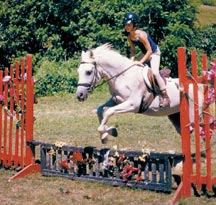

Chrissy’s Loss

Two springs ago, I got the same call on my way to work with Chrissy, who was on Easter break. Our Arabian gelding D’Orsaz was down. The night before, we had brushed and spoiled him with special treats, and he was down? “It can’t be that bad,” Chrissy innocently reassured me.

I could only say, “We have to do the right thing, whatever it is, okay?”

“Yeah, but I still get to ride him on Saturday, right?”

“Sure.”

All I can say about the next several hours is that they were terrible. Nothing could be done to save my beloved friend of 25 years and half a lifetime. His ruptured stomach could not be repaired. The night before, when I happily stroked his neck and whispered how beautiful he was, had been a gift from whatever watches over humans who love horses. The only thing I could do, as my horse’s caretaker, was to relieve him of his pain and send him across the rainbow bridge.

Tangier’s Coming

So Tangier came into our lives. I found him on an Internet search; coincidentally, he is a close relative to the horse I lost. He lived on Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay; hence his name. He had never seen a hill or a creek. We were told he couldn’t jump and that he wasn’t good at horse shows. But his beauty took our breath away, as his playful spirit stole our hearts. When my 15-year old daughter, Elin, got on his back, they connected like a plug going into a socket that turns on a lamp. “We can work with him,” I confidently told my girls.

What a lot of work it was! I couldn’t even get on him when he danced and fidgeted. He had to learn how to put his feet to go up and down hills. His trot was so big we had to learn how to move with him, and he had to learn that mud and water would not swallow him whole.

But Elin fell in love with him and he with her, and they enjoyed a summer of jumping and horse shows and many ribbons. For a turbulent year, he was the only link between her and me. No matter what our differences, we could always talk about Tangier. I could see growing in her the same bond with a horse I had had, and I rejoiced for her, especially during the times when I was not sure how to survive her teenage tempests.

Tangier Down

As I drove slowly down the farm road, I refused to think about what I might face. I remembered my old friend thrashing his head against the stall wall and throwing himself to the ground in agony. As long as I didn’t know, it might not be happening.

My barn manager pointed me to where Tangier was lying. I stood behind him and rubbed his ears and neck. “Would you like to get up and take a walk with me?” I asked.

|

| Rider Elin and Arabian Tangier tolerate the adjustments of author-mother-owner. |

He looked around at me, his expression changing from grumpiness to surprise. He seemed to say, “Hey! What’s happening. Are we going to have some fun?”

The fact the horse showed any interest in me was encouraging. When he stretched his legs in front and pushed himself off the ground, a fragile hope flickered in me that we might be able to beat this. The ancient remedy of helping horses through colic is to keep them up and walking. If the pain forces the horse to lie down and roll, the intestines can twist and kink, cutting off circulation or rupturing, which is fatal — even if surgery is available. Just getting a horse to the operating table involves trucks and trailers — if he can stay upright for the trip.

We had to wait an hour for the veterinarian. I was determined to keep Tangier up, but there were times when he would stop, and with a look of apology, sink down to the frigid earth. I would stand beside him and whisper, “Okay, just for a moment, but please don’t roll. Please don’t roll.”

The vet grimly inspected him, from his gums to his tail. He shook his head, as he said to me, “You know, by this horse’s heart rate [it was 72, while a normal rate is 36], he should be in surgery. But he doesn’t show his pain, and his gums [an indicator of circulation] look good. Either he is incredibly stoic, or he is trying so hard …

“Surgery is an option. But we can first try tubing him with hot water and Epson salts and walking. Do you think you can do that?”

Two years ago the vet and I had struggled to save my other horse. He did not have to tell me what might happen. He wasn’t just asking if I would take the time to treat this horse, but if I had the guts to go all the way through if the treatment did not work.

All my ‘I gotta’s’ flooded my mind. I gotta go to work, I gotta finish a project and I gotta get something in the mail.

He lifted his eyebrow as if to challenge me. Did I have it in me?

There was only one way to find out, and this brave and generous creature could easily die if I didn’t try. I really did not know if I could do it, but we had to start walking right now.

Fifteen minutes of walking, then 15 minutes of rest. Walking helps the horse digest as the pressure of the ground striking the horse’s hoof bottom, or frog, acts like a mini-pump and helps push the blood throughout the system.

In two hours he would call me to check how Tangier was doing. Of course, by then it might be too late for surgery. In effect, by 11:30 that morning, I might have a dying or surgery-needing or recovering horse. I hoped I could get through the next two hours.

Walking Tangier

This was the coldest day of the winter, and I was in office attire. No matter and no time to do anything about it. We walked up the gravel road, across the bridge, over the creek. We checked out the fence lines and the back pastures. He nibbled at dried grass hanks and rubbed his head against my back. Four times, as we rested, I rubbed his sides and ordered and pleaded with his intestines to straighten out.

At 11:30, when the vet called me, Tangier was nibbling some hay. “That’s a good sign,” he said “Keep it up and I’ll call you at 1:30.”

The next two hours, Tangier walked me. My cheeks, toes and fingers were frozen, my eyes and nose ran from the cold wind. I was starving, and the hay that Tangier stuck his nose into during our rest stops was starting to look good to me.

|

| In the happy spring of both their lives, Chrissy takes D’Orsaz over a jump. |

At 1:30, the vet called and said, “We’re not out of the woods yet.” Offer him some bran mixed with warm water, and I’ll call you back at 3.” The bran mash sounded great — for me.

For Tangier, the most curious horse I have ever known, this last session was a magical mystery tour. With his ears pricked and his nostrils flaring, he delighted in all the sounds and smells carried on the frigid gusts. He pulled me along as I stumbled behind him on numb feet. I huddled against his shoulder to escape the wind and looked with envy on his hairy face. Puny human!

Just before the 3 o’clock call, I was able to run home, change and get something hot to eat. Chrissy was surprised to see me and thought with delight that I had come home early to stay with her.

When I told her that Tangier had colicked and I was walking him, she became subdued. She had been there, kneeling on the ground, when the vet squeezed the hypodermic needle into the neck of her beloved friend, and took him away from her forever.

“Please don’t let him die, Mom,” she whispered to me.

“I’m doing the best I can,” I replied — and realized I said the same thing to her when she pleaded with me to save her horse. She turned away into her room, closing the door.

I had not even called her school to say she was sick. I made the call now as Elin walked in the door. Then we raced to

the barn for the call from the vet.

Deliverance

Elin fussed over Tangier while I talked to the vet. We had to take certain precautions for the next three days, but the immediate danger had passed.

Elin, I saw as I filled with relief, was standing next to Tangier. Her forehead was pressed against the curve of his neck, just behind his cheek. It was the same way I had communicated with my old friend, during my 20s, 30s and 40s. His head was turned to her as she murmured to him, and he nuzzled her arm with his upper lip. I gave thanks to the god of horses and the people who love them for this second chance.

The next day Chrissy got in trouble for not doing her homework, which I had forgotten to pick up. She was incredulous when she told me.

“I told my teacher that you had to walk Tangier all day. She said she did not believe me because no one would do that for an animal!”

“That was no animal, that was my horse,” I joked. And he is alive.

|

|