|

|

The Year of the Turtle

by Martha Blume

Some of us go to work every day. Chris Swarth goes on a treasure hunt — sometimes on foot, sometimes paddling a kayak, sometimes diving into tangles of greenbriar and poison ivy. Undeterred, he listens for a signal, an indication, a sign that his quarry is near at hand.

What treasure does he seek? Not gold or silver but a gem of bones, scales and muscle — a living, moving fossil — a work of standard-setting endurance that is endearing to even the most hardened of heart: the female box turtle.

Swarth has been studying Eastern box turtles and red-bellied turtles at Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary since 1995. He’s so steeped in turtles that he’s editing the book on the subject. Due out this month, The Ecology and Conservation of Turtles of the Mid-Atlantic Region — with joint editors William Roosenburg of Ohio State University and Erik Kiviat of Bard College in Annandale, New York — summarizes the population status and ecology of turtles of the mid-Atlantic region, from Virginia through New York.

I wonder why turtles. And does Swarth’s research have anything to say to us about habitat, species conservation and environmental health in Maryland? After spending some time looking at his work and listening to him talk turtles, I have some answers.

But first the story must begin, as it did several springs ago in the marshes of Jug Bay.

Herding Turtles Herding Turtles

May 9, 2000

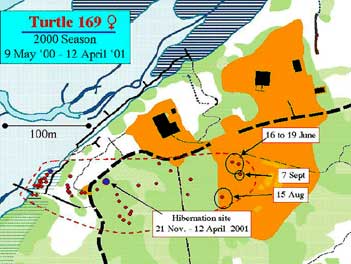

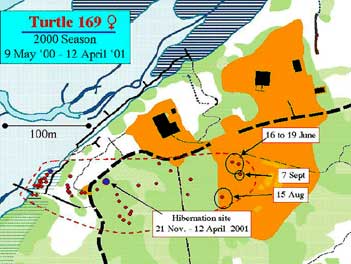

Day 1 in the study of turtle #169, a female Eastern box turtle, Terrapene carolina. Today #169 gets her transmitter.

Swarth shows me the unit. It’s about an inch square, powered by battery with attached antenna, which is glued with epoxy to the turtle’s upper shell. The battery weighs about 10 grams, the turtle about 500.

Does it bother the turtle?

No, Swarth assures me, it’s like you carrying a purse, he says. I don’t carry a purse, so I can’t relate. But Swarth has seen mating turtles with the transmitters attached and knows they don’t get in the way. That’s a crucial piece of information for a turtle biologist.

Turtles and their ecology have intrigued Swarth since he moved to Maryland in 1987. A master’s in biology from Hayward State University in California and a job as director of Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Lothian give him the credentials to get paid to do the work he loves.

“We have a really rich community of turtles here in terms of species,” says Swarth of the turtles at Jug Bay. “There’s eight different types and there’s lots of them.”

How do box turtles use habitats? That is the question that began his research, for, he says, “several different habitats — including wetlands, forest and open meadow — comprise the sanctuary.

“An ecologist needs to know where an animal moves to throughout its annual cycles, what habitats it uses, to get a complete picture of its needs,” he says.

Swarth and his interns and volunteers began their research using painted turtles, which are abundant and easy to catch. They studied where the turtles lived, practicing a technique of marking the turtle shells.

“Turtles are great because you can file a notch in their shells,” Swarth explains, “and be able to know if you’ve found them again.” I incorrectly assume he means that every turtle gets the same notch to indicate it’s already been counted.

Actually, it’s a lot more exact than that. Swarth shows me a turtle shell. He explains: “We give each turtle its own unique number. Each painted turtle has its own set of notches in its shell. It’s cool.”

The turtle shell is made of bones covered with scutes. The scutes are made out of the same material as our fingernails.

It turns out that every turtle species has a set of 20 to 24 marginal scutes around the edge. This allows for hundreds of combinations of file marks. Swarth and his team have labeled about 1,400 turtles of all eight species at Jug Bay. They can identify each one as an individual. That is cool.

After the turtle is marked and fitted with her transmitter, she is released to go about her turtle business.

The Turtle and the Egg

May 9 - June 14, 2000

Box turtle #169 is milling about in the marshy wetland habitat at Jug Bay. The fact that this turtle and the other 409 box turtles that Swarth has tagged spend so much time — from weeks to months — in the marsh changes box-turtle science.

“I started looking at box turtles in wetlands because almost nothing has been published on the use of that habitat by box turtles. Most previous research describes box turtles as forest animals,” he says. “I wanted to thoroughly document their use of wetlands.”

Swarth’s research is funded by Anne Arundel County, the Friends of Jug Bay and the Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

He focused on females because their habitat needs are greater than those of males. Females require both foraging and nesting areas. The production of viable eggs may depend on the female’s access to nutritious and abundant food; egg development depends on suitable nesting habitat.

On the Move

June 16 - 19, 2000

Turtle 169 is on the move.

These turtles can move one-half to three-quarters of a mile in 24 hours. Or they can sit in the same location for days.

“Tracking can be easy in open areas,” says Swarth. “But it can be a struggle when turtles move long distances suddenly or when they enter dense, marshy tangles.” It’s hard to picture a turtle doing anything suddenly.

Turtle 169 is discovered upland on a sunny meadow, about one-quarter mile from her location two days prior. What’s up? The turtle is looking for a warm and sunny spot to mingle and mate.

Turtles typically lay their eggs the first two weeks of June, placing four to six eggs in a nest made by digging a hole in the ground, laying the eggs, covering the eggs with dirt and then abandoning them. The eggs are laid three or four inches underground and incubate by the heat of the sun and the heat of the soil. Swarth found that 80 to 100 percent of these eggs will hatch if they are protected from predators.

Female box turtles can begin to lay eggs when they reach sexual maturity, around age five. They can continue their egg laying throughout their life span, which can reach 70 years or more.

Home on the Range

June 20 - September 7, 2000

Swarth describes his treasure hunt with the enthusiasm of a kid looking for Easter eggs: “Each turtle transmitter sets off its own frequency. We set our receiver to the frequency of that turtle and aim our antennae out in the direction we think the turtle may be. If the sound increases in intensity, we know we’re on the right path of the turtle.

“ When we find the turtle, we map its location and note where it is, what it’s doing, the time of day and the turtle’s temperature. We do this over a season.” When we find the turtle, we map its location and note where it is, what it’s doing, the time of day and the turtle’s temperature. We do this over a season.”

Swarth and his volunteers try to find every turtle every other day.

During mid- to late-summer, Turtle #169 is found moving between marsh, forest and meadow.

Swarth’s telemetry studies allow him to map the turtles’ home range, where it spends its time over the course of a season. Home range must include all the resources the animal needs to survive. Knowing an animal’s home range is vital information for a resource manager when planning for the conservation of a species. A typical turtle home range may cover four to five hectares or 10 to 12 acres.

Number 169 lays two more clutches of eggs in the meadow this season, one on August 15 and another on September 7.

Swarth tagged and followed 35 females from 1998 until last year. Some turtles’ habits were surprising. Take #128. The first season of the study, her home range covered about five acres. The second season, she went traveling. Trackers found her outside the sanctuary on two occasions, possibly to nest in adjacent farm fields, stretching her home range to 25 acres.

Swarth found that some turtles lay no eggs in a season, some nest one time and some several times. He is looking for factors that explain the variance in nesting patterns. But all seem to prefer the warm and sunny meadows for nesting.

Long Winter’s Nap Long Winter’s Nap

November 21, 2000

The treasure is located in a densely forested area. It’s time to settle in for a long winter’s nap. Box turtles hibernate under a layer of leaf litter to about the depth of their shells or an inch deeper, so that the top of the shell is an inch or two below the surface of the soil. The warmth of the forest layer protects them from subfreezing temperatures.

Number 169 stays under her forest blanket until April 12, 2001, when she emerges to begin her new season of traveling and nesting. Her entire home range is less than one-quarter a square mile, but she clearly depends on a variety of habitats for the stuff of her life.

Turtles as Teachers Turtles as Teachers

Swarth’s box turtle studies raise red flags on environmental health in Maryland and beyond. Box turtles are not endangered, but they are, like all turtle species in Maryland, declining.

Turtles are one of many species dependent on our ever-decreasing wetlands. Swarth’s tracking showed that box turtles use wetlands for significant amounts of time. But perhaps more important, his research shows that they need a mix of habitats: forest for food and cool temperatures; wetlands for rehydration and food; sunny, open sites for mating and nesting. A fourth part of their home range is corridors for safe passage between these habitats.

Corridors are important not only to turtles but to a variety of wildlife — black bears and wildcats and small mammals like opossums and raccoons — that migrate short or long distances in their own home ranges. Housing developments, roads and strip malls act as walls in these corridors, cutting off wild creatures from critical habitat and from one another.

Even apparent abundance doesn’t mean a population is healthy and breeding.

“You may see the same turtles year after year in your backyard or neighborhood but these turtles are probably not reproducing,” Swarth says, because they can’t reach other box turtles or mating and nesting sites.

The very gene pool — that collection of all the possible genes that make up a box turtle — could actually change if populations of turtles are cut off from one another, leading to low gene diversity and unhealthy populations.

It’s Not Easy Being Slow

Interruptions in natural corridors pose other risks to turtles. Having to navigate roads to get from meadow to wetland or wetland to forest is plain dangerous.

“They get squished,” says Swarth. “Road mortality is a huge problem.”

Another problem is people who unwittingly pick up a turtle they find in the road and carry it to a park or another natural area. Swarth likened such displacements to giving me a spoon and a cup and plopping me down in Kansas. I’d be completely out of my element and physically separated from anything akin to home and sustenance. Besides that, if people constantly transplant turtles to parks, the population may explode beyond the resources available.

“People are well-intentioned,” he says. “But what they should do is to help it to the side of the road it was headed for and leave it.”

Turtle Inspiration Turtle Inspiration

As a red flag for wetlands conservation, plenty of other species might be considered more titillating than turtles. So I ask Swarth, why turtles?

After some reflection, he offers this:

“They’ve been around for over 250 million years. They’ve outlived dinosaurs. They clearly have a strategy for survival that works. They’re an important part of an ecosystem. They eat vegetation, they eat insects, they eat fish, so they play a role in maintaining an ecological balance. Their eggs and their young are important prey for big fish and for birds.

“And they’re interesting because they are very long-lived and they’re attractive. Most species have pleasant personalities. You can get your hands on them and mark them as individuals.”

It’s clear Swarth loves turtles. Even when his conservation crew comes in for a day’s work, he wants to keep talking turtles. The research and education do ne by him and his staff at Jug Bay will, he hopes, help box turtles wherever they live.

Finally, it’s not only turtles that benefit from their partnership with Chris Swarth and Jug Bay. The scientists are also better for the time they spend with turtles.

“Studying marked individual animals teaches so much more than studying animals that you don’t know personally,” says Swarth. “The message I draw from this is that there’s just a lot of variation in the world. We tend to describe the ecology of an animal in generalities. We describe the average situation. When you have a sample of animals that are marked as individuals — whether warblers or grizzly bears or turtles — the range of variation becomes apparent. Your horizons broaden, and you realize that the natural world is always more complicated than you imagined.”

Meanwhile, back at Jug Bay, Swarth still has questions to answer: Is nesting productivity directly linked to wetland resources available to females? Do turtles need wetlands more for food or for temperature regulation?

Want to help on turtle studies? Write Chris Swarth or volunteer coordinator Christina Miller at Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary • jugbay@toadnet.

About the Author:

“The Year of the Turtle” may be Martha Blume’s last feature for Bay Weekly. For three years, Blume has combined her master’s degree in environmental education with her gift for words. Now, following Coast Guard orders, the Blume family is setting sail for New Haven, Connecticut. |

|

|

|

Herding Turtles

Herding Turtles

When we find the turtle, we map its location and note where it is, what it’s doing, the time of day and the turtle’s temperature. We do this over a season.”

When we find the turtle, we map its location and note where it is, what it’s doing, the time of day and the turtle’s temperature. We do this over a season.” Long Winter’s Nap

Long Winter’s Nap Turtles as Teachers

Turtles as Teachers Turtle Inspiration

Turtle Inspiration