|

Not Just for Birds

Even in summer, feeding the birds is for kids — and grownups, too.

story and photos

by Vivian I. Zumstein

My eight-year-old daughter, Emily, gazes out the kitchen window at the birds gathered at our feeders. “Oh, look!” she exclaims, “There’s one we’ve never seen before.”

A small, round bird has caught her attention. It is so dull that I am surprised she noticed it amid the dozens of birds in this morning’s large, hungry flock.

The ornamental plum tree is filled with birds vying for position. Our regular visitors — chickadees, titmice and various finches — dive by and across my window frame. I notice three mating pairs of cardinals; the males make dramatic crimson splashes against the green bushes. A red-bellied woodpecker and a few smaller downy woodpeckers dine at the suet feeder. On the ground, a scattering of sparrows, a few towhees and the unknown visitor are gleaning seeds dropped from above.

Emily grabs our Audubon Society identification guide. Her eyes dart back and forth from the book to the bird while she flips the pages. The new visitor is a rather plain bird, mostly a dull brown with a white chest patch speckled with brown. Its only distinguishing feature is a rather round shape. Suddenly Emily stops, her finger poised above a photograph in the book. After another long, studious look at the bird, she gives a satisfied little nod and announces, “It’s a hermit thrush.”

Birds for Breakfast Birds for Breakfast

Like many parents, I want my children to experience the wonders of nature. In this harried world of homework, music lessons and endless activities, where could I find time for regular nature expeditions? There was always some conflict: a soccer game here, a science fair project there.

The solution? Instead of going to nature, I brought nature home. Bird feeders in our backyard have attracted a surprising variety of birds, and we enjoy their visits from our kitchen table. Kids who are eating peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches find it great fun that some birds, especially Carolina wrens, like peanut butter as much as they do.

That’s why we’re feeding our birds all summer, when many people have washed and stored their feeders for the season.

It’s true that winter feeding supplements a scarce diet for wild birds. Bird visitors to new summer feeders will not be as numerous because natural food grows plentifully. However, chickadees, titmice and finches will find feeders no matter the season, setting the stage for greater variety in the fall.

On the other hand, summer is hummingbird season. Keeping feeders up from May through October will not only attract our summer visitors but will also support hummingbirds in their migration through our region. Watching a jewel-colored hummingbird zip around the yard and then hover at a feeder makes birders of children and parents alike.

“Feeding the birds is for humans, not for birds,” says Andy Brown, senior naturalist at Battle Creek Cypress Swamp Sanctuary.

Birds Make Good Teachers

Brown is a strong advocate of early nature education, for he knows that children exposed to nature “develop an appreciation and love of the environment that carries through life.”

To make his point, he likes to relate the story about a girl who had attended nature classes at Battle Creek Cypress Swamp Sanctuary as a preschooler. Years later, and after no more nature classes, the girl turned up on the seventh grade softball team with Brown’s daughter. One day, a caterpillar joined the team in the dugout. With typical adolescent revulsion, most of her teammates recoiled from it. “Yuck! Gross!” they shrieked. Brown’s former student cradled the caterpillar and placed it safely in a nearby tree. She had learned not to fear nature but to nurture it.

Children’s own natures are also developed by what they learn in nature. Curiosity is innate in young children. They enjoy learning new information, and they retain what they learn. “Starting young, taking the time to watch helps kids focus and concentrate,” says Brown.

From watching birds, kids learn more than simply who’s who. They develop and hone skills in observation, comparison and decision-making.

To identify a bird a child must first carefully observe it, then make comparisons between the features of the unknown bird and those of various bird groups. Once the basic group is identified, comparisons continue in a series of ever more refined decisions to determine which specific species the bird matches in an identification guide.

In addition to these skills, feeders offer another advantage: Children can study a bird rather than try to identify it after catching only a fleeting glance of it in the field.

Strong skills in these areas can contribute to success in school. “Making comparisons, like the shape of a bill or the size of a bird, are all mathematical applications,” says Brown. “And any types of observation are good to develop for academics, especially science. Science is all about making observations.”

Birds on Candid Camera

Best of all, watching birds is fun. Many children like observing the behaviors of familiar birds and identifying new, often transient visitors. My youngest child, five-year-old Tommy, especially likes the nuthatch. He laughs and announces its arrival: “Here comes the nuthatch again.” I follow where Tommy’s finger is pointing. Sure enough, there is a white-breasted nuthatch making its unique and comical staccato head-first way down a tree branch.

Observing birds is entertaining because birds at feeders act naturally. For example, cardinals almost always show up at our feeder in mating pairs. The less colorful females come quickly to feeders while the brilliant males hang back in the underbrush until they are certain there is no danger. While feeding, males remain more wary than females and scatter at the slightest hint of a threat.

Observing birds is entertaining because birds at feeders act naturally. For example, cardinals almost always show up at our feeder in mating pairs. The less colorful females come quickly to feeders while the brilliant males hang back in the underbrush until they are certain there is no danger. While feeding, males remain more wary than females and scatter at the slightest hint of a threat.

In contrast, chickadees and titmice are tough guys. Despite their diminutive size, they are fearless creatures. They do not hesitate to come to feeders even when humans are near. In fact, it is not unusual for both species, but especially chickadees, to collect in tree branches only feet away while I refill feeders. The birds twitter incessantly as if I am a trespasser and they are ordering me off their turf. The moment I step away, the birds swoop in to reclaim the feeders.

You’ll also see the cycles of life at your feeder. In early spring, mating rituals go on display. In courtship feeding, the male offers a tidbit of food to his mate. In summer, adults often bring their young to feeders. The juveniles endlessly pester their parents. They crouch low, utter plaintive cries and flutter their wings, mouths opened wide, begging to be fed.

With some reading and just a little practice, common bird behaviors are easy to recognize. Children learn the different birds and their behaviors quickly. Many of my children’s friends, and not just a few adults, have been surprised when my children casually explain how to distinguish the difference between male and female red-bellied woodpeckers or point out how chickadees take only one seed at a time, flitting off somewhere else to break the seed open.

Setting the Table for Birds

Countless bird feeders tempt the buyer. Savvy buyers should shop around. Prices for the same feeder vary, often greatly, from one source to another. Brown recommends variety. “The more different types of feeders and different foods you provide, the greater the diversity you will attract,” he says.

To attract goldfinches, titmice, doves, juncos, towhees, sparrows and red-bellied woodpeckers, to name only a few, consider a tube feeder with sunflower seeds, a tray feeder with millet or mixed seed and a suet feeder with suet cake. One hundred dollars covers the cost of three basic feeders and seed — though you can easily spend more on fancy feeders.

|

Basic Bird Menu

|

Sunflower seed attracts a large variety of birds, including finches, chickadees, cardinals, titmice, nuthatches and grosbeaks.

|

Suet and suet/seed mixes attract woodpeckers, nuthatches, wrens, titmice, jays, brown thrashers, pine warblers and northern mockingbirds. Purchase or mix at home.

|

millet attracts small ground-feeding birds such as towhees, doves, juncos and sparrows.

|

Cracked corn attracts the same birds as millet but is more susceptible to spoilage. Use it in small amounts, mix it with millet or put it in feeders protected from water.

|

| Thistle is the most expensive birdseed. It is a favorite of goldfinches, which are stunning in their breeding plumage of gold and jet black. Other finches are also attracted to thistle. |

To start small, choose a hanging suet basket. They cost under $4, and the suet that goes inside ranges from 99 cents for plain to $3 or $4 for fancy. Chickadees, titmice, woodpeckers, jays and nuthatches love suet and repay you with the antics of a team of comedians.

When you want to expand, Brown suggests a tray feeder to draw the greatest bird diversity. Simple ones cost under $30, or you could easily construct one. Sparrows, doves and towhees congregate at tray feeders. Tray feeders also attract the flashy red cardinals, which prefer to feed on or closer to the ground. Best of all, this type of feeder acts as a natural stage for a surprising array of bird behaviors. More spacious than hanging feeders, tray feeders offer birds greater freedom to demonstrate their true personalities.

A small window-mounted feeder (under $30) brings birds even closer. Window feeders attract small, brazen birds that are not intimidated by the presence of people on the other side of the glass. So you’ll get a good show.

A terrific but more expensive window-mounted feeder (starting at $68) includes a one-way mirror. The birds see only themselves, so you see them from inches away. Birds at this feeder provide surprising entertainment. Male birds, especially during mating season, may mistake their own reflections for territorial rivals and have heated, though harmless, battles against themselves.

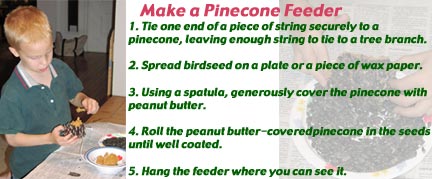

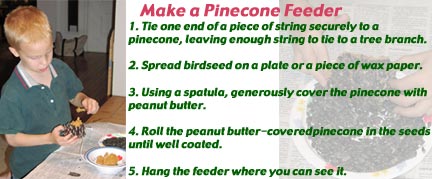

Children also enjoy building their own feeders. Birds aren’t fussy. Seed contained in a used plastic bottle is just as attractive to them as seed in an expensive Plexiglas tube. And the kids gain an almost immediate interest because they want to see the birds eating from their feeder. See www.birding.about.com for do-it-yourself projects.

Serving water as well as food brings more birds to backyard feeders.

Studies show birds do not become dependent on feeders, so the frequency of feeding is your choice. If you want a steady flow of birds at the feeder, keep the feeders filled with seed. If you are going out of town for a couple of weeks, fear not. The birds will find other food sources in your absence and will return to your feeder once it is refilled.

Feeding the birds need not be expensive. Purchasing seed in bulk keeps the cost down. The smaller the bag, the higher the cost. Store large amounts of seed in dry, covered containers to prevent spoilage.

As to mess, yes, you’ll have some: plenty of empty seed hulls, not to mention the droppings that appear wherever birds congregate. Bird books recommend you routinely rake up empty hulls that collect under feeders. Feeders should also be taken down and thoroughly washed regularly. This ensures a supply of healthy seed. I confess that I am not a particularly fastidious bird feeder. I never rake the hulls. I don’t need to: My hungry Labrador licks them up for me. I only occasionally find time to wash the feeders; however, I have not noticed my seed going bad or sick birds lingering in the vicinity of the feeders.

As for the droppings, I find a good old summer thunderstorm effectively washes away all the evidence, at least temporarily. If it’s a choice between a clean walkway or the birds, I’ll take the birds.

Now, where do you put your feeders?

Bird books generally recommend feeders be hung on poles in the open but near some protective cover, such as bushes or a woodpile. This placement allows birds to notice the approach of predators, primarily cats but in some cases dogs, and gives them safe places in which to take refuge. Hanging them in the open also allows birds to discover new feeders more easily and reduces the risk of their flying into windows.

On the other hand, you want to see the birds you’re feeding. So you’ll need to strike a balance between safety for the birds and good viewing for you.

We placed our feeders close to the house, where they hang in a tree surrounded by low, thick landscaping only feet from our kitchen table. Bushes provide plenty of cover for shy, ground-feeding birds that might not visit feeders in a more open area. Squirrels like the location, too.

The Squirrel Dilemma

Squirrels can be frustrating; how much of a frustration they become depends on your perspective. The tricky rodents defeat even so-called squirrel-proof feeders. Their efforts defeating these feeders, however, may be great and therefore amusing to watch.

I have observed a squirrel stretched to its full length, dangling from its hind claws over the edge of the slick metal roof of a squirrel-proof feeder to pilfer one sunflower seed at a time. After eating four or five seeds, the squirrel lost its tenuous grip and fell to the ground with a solid thump — only to climb back up to repeat the precarious process again and again. With such an acrobatic expenditure of energy, I did not begrudge the creature a few seeds.

Squirrels are part of nature, too, Brown advises. They do not realize humans intend the seed be for birds. They only see a plentiful food source. He suggests that the best way to deal with squirrels is not to prevent them from coming to feeders but to distract them. Setting up a platform feeding station with inexpensive cracked corn in the vicinity of bird feeders often deters squirrels from eating more expensive seed and damaging feeders.

Beyond the Basics Beyond the Basics

Families fond of birds have numerous directions in which to branch out. They can seek more and different birds in local nature parks, or they can expand activities in their own backyards with, for example, nesting boxes or bird-friendly landscaping.

“It is a good idea to get involved in making your yard bird-friendly, especially by planting things that provide food over the winter,” Brown says. “Berry-producing shrubs are good.” Landscaping for the birds can be a one-time effort, especially if you plant native species — which, Brown says, “are hardy and require almost no maintenance.” Visit the web site www.nestbox.com provides specific recommendations on what to plant for local bluebirds and hummingbirds and contains links to other wildlife landscaping web sites.

Nesting boxes in the yard help draw a larger number of birds to feeders. But you must make a bigger commitment, for the boxes require more maintenance than do feeders. They must be checked and cleaned periodically. The rewards, however, are great. Children thrill at watching birds build a nest, then witnessing the birds develop from eggs to fledglings.

Nesting boxes are especially appealing to Eastern bluebirds. They work better than feeders for attracting bluebirds to a yard. According to Arlene Ripley, coordinator of the Calvert Bluebird Council, bluebirds do not routinely explore looking for feeders. They only come to feeders in areas where they are already established. Even then, bluebirds almost need to be trained to come to feeders. To learn about building and maintaining nesting boxes, visit www.nestbox.com.

Farther afield, short trips will take you to birds that don’t come to feeders around the Bay. At local parks, depending on the park and the time of year, visitors may spy the great blue heron and a variety of migratory waterfowl or raptors, such as hawks, eagles and osprey. A pair of bald eagles nest in the vicinity of Flag Ponds Nature Park. Park visitors often spot them fishing in the Bay just off the park’s beach. “These days, seeing bald eagles at Flag Ponds is almost guaranteed,” Brown says.

Calvert County families need go no farther than their local sports complex — Dunkirk District Park, Cove Point Park or Hallowing Point Park — to get a close look at an osprey. Many a T-ball game has abruptly come to a standstill while players and parents pause to gape at an osprey swooping down to its nest atop a light stanchion. The drama is further enhanced if the bird is clutching in its talons a large fish for its nestlings.

Calvert County families need go no farther than their local sports complex — Dunkirk District Park, Cove Point Park or Hallowing Point Park — to get a close look at an osprey. Many a T-ball game has abruptly come to a standstill while players and parents pause to gape at an osprey swooping down to its nest atop a light stanchion. The drama is further enhanced if the bird is clutching in its talons a large fish for its nestlings.

Such events both surprise and amuse. During the osprey’s recovery from the effects of DDT, conservationists insisted these birds needed plenty of quiet. Nowadays, at least three mating pairs of osprey in Calvert County have chosen to build their nests atop light stanchions illuminating baseball fields, amid loud and energetic human activity.

Battle Creek Nature Education Society in Calvert and Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary and Kinder Farm Park in Anne Arundel County offer low-cost nature education programs, many of them highlighting birds. Jug Bay, for example, teaches beginning birdwatchers, and Kinder Farm Park has a course in birding for kids and another in family birdhouse building. Find upcoming programs at www.jugbay.org • www.kinderfarmpark.org and • www.calvertparks.org.

Our Private Show

Bird feeding activities can stay confined to a kitchen-window viewing or it can blossom into a passion. I augment our daily bird observations with an occasional family field trip to a local park or a nature course. Still, what I like best about bird feeding is that I don’t need to add to the experience to enjoy it. All I have to do is relax at my kitchen table, angle my chair a little to the left, and my private flock of birds puts on its own little show.

|

Reading Up on Birds

|

Libraries have shelves of books to encourage children’s interest in birds. Try these:

- Backyard Birds of Summer by Carol Lerner.

- The Bird Feeder Guide: How to Attract and Identify Birds in Your Garden by Marcus Schneck.

- DK Eyewitness Explores Birds by Jill Bailey and David Burnie.

- Finding Birds in the Chesapeake Marsh: A Child’s First Look by Zora Aiken.

- What Is a Bird? by Ron Hirschi.

|

|

You’ll also want a book or two at home for ready reference. Stokes Birdfeeder Book:

- The Complete Guide to Attracting, Identifying and Understanding Your Feeder Birds by Donald and Lillian Stokes covers attracting and observing birds and provides good information on birds likely to visit local backyard feeders.

- A bird identification guide is essential. The National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds (Eastern region) by John Bull, et al., includes outstanding photography and detailed information. It’s designed as an adult book but is easy enough for my eight-year-old.

- Prefer a guide aimed at fledgling users? Try Peterson First Guide to North American Birds by Roger Tory Peterson.

|

|

|

Birds for Breakfast

Birds for Breakfast Observing birds is entertaining because birds at feeders act naturally. For example, cardinals almost always show up at our feeder in mating pairs. The less colorful females come quickly to feeders while the brilliant males hang back in the underbrush until they are certain there is no danger. While feeding, males remain more wary than females and scatter at the slightest hint of a threat.

Observing birds is entertaining because birds at feeders act naturally. For example, cardinals almost always show up at our feeder in mating pairs. The less colorful females come quickly to feeders while the brilliant males hang back in the underbrush until they are certain there is no danger. While feeding, males remain more wary than females and scatter at the slightest hint of a threat.

Beyond the Basics

Beyond the Basics Calvert County families need go no farther than their local sports complex — Dunkirk District Park, Cove Point Park or Hallowing Point Park — to get a close look at an osprey. Many a T-ball game has abruptly come to a standstill while players and parents pause to gape at an osprey swooping down to its nest atop a light stanchion. The drama is further enhanced if the bird is clutching in its talons a large fish for its nestlings.

Calvert County families need go no farther than their local sports complex — Dunkirk District Park, Cove Point Park or Hallowing Point Park — to get a close look at an osprey. Many a T-ball game has abruptly come to a standstill while players and parents pause to gape at an osprey swooping down to its nest atop a light stanchion. The drama is further enhanced if the bird is clutching in its talons a large fish for its nestlings.