Where’s the Beef ?

Where’s the Beef ?

There’s More than Corn Growing in Chesapeake Fields

by Jessie McLean Heller

The school day is finally over, and, fresh off the bus, Danny Gibson makes the switch: school clothes to farm clothes. Then it’s past the barn and down the hill, blue jeans brushing through the long grasses. The cows bellow out a kind of greeting, and the young boy circles them, herding them closer together until he can step behind and urge the group forward. The spring breeze keeps the flies scattered as they buzz around the cows’ ears, and the sun is warm on the young farmer’s hair.

Plodding up the hill, two-legged creatures struggle more than four-legged. The cows savor orchard grass, working it with their teeth like chewing gum as they stroll up a pasture hill. But Danny Gibson is sweating and his breath comes hard. He’s happy when they see the top of the hill.

Just then a cow decides she wants to part ways with the rest. Her body swings around, and she is headed back down the hill before Danny can cut her off. “Ho there! Ho!” his voice follows her down the hill. He scrambles to stop her, and the herd breaks apart; the rest work their way down the long hill.

The boy groans, but many years later the 67-year-old chuckles as he remembers that hill and his early days working with cows.

“I’ve been blessed,” says Danny Gibson as he looks out across his Huntingtown fields, filled with hay bales that will feed his cows. And those cows will feed us … if we’re lucky.

Most people go to the meat section of their grocery store when they want hamburger or steak for dinner, which is good for farmers who sell wholesale to grocery stores. There are also farmers, like Danny Gibson, who market their beef themselves or through a local butcher shop.

So who’s who, and why should you care as you set up your grill to make hamburgers?

From Grass to Grill

In general, grocery stores sell beef that is grown on the largest farms, out in the Midwest. Area butcher shops, in contrast, sell beef that is grown locally on smaller farms; sometimes area farmers themselves also sell their beef. This locally grown beef is different from beef grown on big Midwestern farms.

On the largest farms, farmers with big herds typically treat their beef with antibiotics to keep the cows disease-free. Large cattle operations also tend to use hormones to speed growth. Hormones and antibiotics in meat raise health questions.

Recently, for example, McDonald’s has requested that its suppliers stop using antibiotics. Why? Growing meat with antibiotics leads to the evolution of antibiotic-resistant germs that have a picnic when they hop over to people and are no longer treatable with common antibiotic drugs.

Local farmers, for the most part, do not use antibiotics or hormones because smaller herds tend to stay healthy naturally. Even among area farms that grow this “clean” (hormone- and antibiotic-free) beef, there are different ways of getting beef onto your grill.

Most local farms raise their cattle on pasture, finishing up on grain to fatten the beef. The alternative to finishing on grain is to raise strictly grass-fed cattle, which creates leaner beef that has other health benefits as well. But grass feeding from beginning to end is harder work, and thus more costly.

There are also differences in the ways farmers fertilize and fight weeds. Farmers who do not use synthetic fertilizers to grow their feed and do not use pesticides to kill weeds are farming organically. Many local farmers do use chemicals to grow feed and to manage weeds. Some worry that they could not survive if they had to meet organic standards.

As suburbs spread into farmland in Chesapeake Country, farm survival is a growing concern. Our need for food, however, lines up with the farmers’ need to market what they grow, and meat is the base for many of our meals. Understanding the way beef is grown gives us more control over the way we eat, and our choices, in turn, affect the future supply of that beef.

People Want Beef

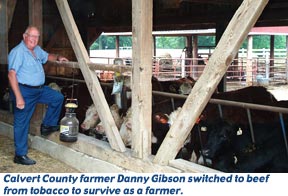

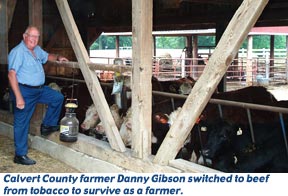

Calvert County Farmer Danny Gibson knows people want beef. He switched to beef farming from tobacco farming in order to keep working the land.

“There are people who know they want clean beef,” says Gibson, whose cows receive no growth stimulants or antibiotics. “The feed is barley, soybean meal, corn, minerals. And that’s it. No additives,” Gibson explains.

Gibson has a bull, 22 cows and their calves. The deep red-brown color of his cows — along with several black coats, too — reveal that he has mostly Hereford cows, and a few black Angus. The calves are raised in pasture, but when they’re seven or eight months old and weigh about 600 pounds, they enter a feed lot to get ready for the slaughterhouse.

Gibson has a bull, 22 cows and their calves. The deep red-brown color of his cows — along with several black coats, too — reveal that he has mostly Hereford cows, and a few black Angus. The calves are raised in pasture, but when they’re seven or eight months old and weigh about 600 pounds, they enter a feed lot to get ready for the slaughterhouse.

The feed lot, which is the calves’ base for eating Gibson’s grain mix, is located within and around an old tobacco barn. Gibson says he was lucky to be able to create a concrete feed lot. He calls the concrete floor an “investment.” It cost him initially, but he couldn’t stand for his cows to be up to their knees in mud.

“After a month of rain like we’ve had, there would be several feet of mud if I didn’t have the concrete,” he says, with a fond glance at his calves as they move easily around the lot, stopping to munch at the hay in a trough at the center of the lot.

“I grow my own hay,” Gibson says, “but last year, for the first time, I had to buy hay.”

The drought last year sent Gibson to Garrett County to pick out hay for his cows. And this year, the rain has Gibson behind schedule.

“The tractor tires turn up water when I bale the hay. I can’t do anything with it right now because of the rain,” Gibson says. “A tractor got stuck a few weeks ago.”

Tied to the land, Gibson is tied to the weather, and too much rain or too much shine can change his summer. He doesn’t mind, though.

“I love this place,” he says, “I just feel blessed even to have it.”

At age 67, Gibson manages to run the farm on his own. He has one worker who joins him in the afternoons, but his operation is organized to the point that it doesn’t take full-time help.

“I’ll tell you what,” Gibson says. “My second greatest satisfaction is when someone new tries my beef and calls that night after eating it and says ‘put me on your list.’”

That’s the list of “clean” beef eaters who buy direct from Gibson. Without them, Danny Gibson would lose his greatest satisfaction: working the land he’s known and loved since childhood.

Accounting for the Farm

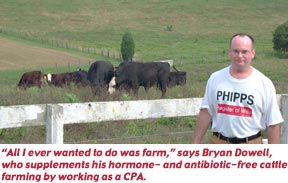

Another Calvert County farmer, Bryan Dowell, feels the struggle for survival, too.

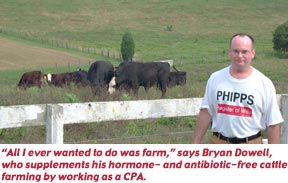

“All I ever wanted to do was farm,” says Dowell,” but I had to go to college because I couldn’t have supported myself just farming.”

He has managed to keep his father’s Prince Frederick farm running and to support himself at the same time. But if you’re looking for a sign marking the Dowell’s farm as you drive by his land, you’ll miss it. The sign outside his driveway says Bryan Dowell, C.P.A. — that’s Certified Public Accountant.

He has managed to keep his father’s Prince Frederick farm running and to support himself at the same time. But if you’re looking for a sign marking the Dowell’s farm as you drive by his land, you’ll miss it. The sign outside his driveway says Bryan Dowell, C.P.A. — that’s Certified Public Accountant.

The accountant has a herd mixed of black Angus and Hereford, 20 cows, but 30 or 40 head on the farm at all times, counting the calves. Like Gibson, Dowell raises his cows on pasture and finishes them on grain, and, like Gibson, he uses no hormones and no antibiotics.

Dowell may have a job besides farming, but he still puts in plenty of work on the farm.

“We have to reseed by hand,” he says, talking about the pastures. “Because of the hills.”

The hills are dramatic in their slope and make up nearly the whole farm.

“I always say, without the hills, we wouldn’t have enough land to farm,” Dowell jokes. He says his grandfather used to plow the hills with horses. Using a tractor is out of the question given the steepness of the land.

Local farmers rise to the challenges of weather and land, and some even try to make sure the land can hold up against the challenges of farming.

Investing in the Land

Bill Doepkins learned farming from his dad. Bill Doepkins Senior cared so much about the insects, the birds and everything on his farm that he refused to use pesticides. He passed this concern on to his son, who has learned that farming without pesticides is also best for the land. This means Doepkins’ cows have never been fed chemicals. The cattle on Doepkins’ Anne Arundel County farm are not only hormone- and antibiotic-free, but they’re also raised on pesticide-free grain.

Doepkins, a full-time farmer in Davidsonville, can feed his red Angus herd chemical-free grain because he grows it himself. Crop rotation and a careful schedule of working the fields help him get the job done without the pesticides or herbicides on which so many farmers depend.

Accurate timing of tillage and cultivating the fields that have been in his family since 1906 are the techniques that replace pesticides for Doepkins. Tillage is plowing and discing, which prepare the land to grow crops. Cultivating is a pesticide-free way of controlling weeds using equipment, not chemicals.

Riding an old Allis-Chalmers tractor, Doepkins cultivates his corn. The cultivator drags along behind the faded orange tractor, pulling out and burying weeds. For these kinds of interactions with the land, the timing has to be right. Too early, too late, too rainy — the farming will not go smoothly.

The effort and flexibility it takes Doepkins to raise his grain without using pesticides or herbicides are investments of a longer term than Danny Gibson’s feed lot. Doepkins invests in the land, so from his style of farming generations to come will benefit as well as people who are now eating his beef. Other farmers are also making this investment.

Beef for the Bay

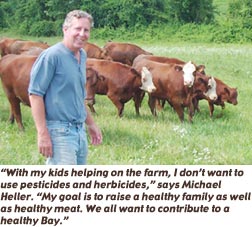

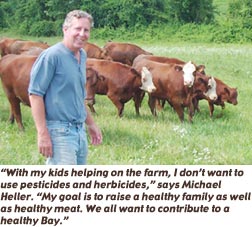

“We follow organic standards,” says Michael Heller, who looks at home sharing pasture space with the cows. As he leans against a weathered fence post he made out of a fallen locust tree, a red Angus looks up from grazing, hopeful that Heller is moving the herd — mixed of black and red Angus — to fresh pasture. The farmer thinks fondly of his cows, so much so that when Heller developed an allergic reaction to eating beef, his family suspected sympathy pains.

Heller runs the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Clagett Farm in Upper Marlboro in Prince George’s County. Meeting organic standards is part of the 20-year-old, 300-acre educational farm’s mission: to find a balance between using the land and using up the land. The orchard grass the cows are enjoying now is part of a diet that doesn’t change. These are grass-fed cattle. Raising cattle on grass allows the farm to produce meat without using chemicals that help grow grain but that harm the land and the Bay. That’s one reason Chesapeake Bay Foundation is interested in grass-fed cattle.

Raising the herd on grass alone also allows the cows to do the work of synthetic fertilizers, diesel fuel and farm equipment. The cows fertilize the pasture with their manure and harvest their feed themselves.

Raising the herd on grass alone also allows the cows to do the work of synthetic fertilizers, diesel fuel and farm equipment. The cows fertilize the pasture with their manure and harvest their feed themselves.

“It saves time and energy,” says Heller, who likes to look at the task as “raising grass.”

“We look at it as grass farming as opposed to cattle farming,” Heller explains. “If we raise the best grass, then we raise the best cattle.”

For that reason, the farm uses lots of clover in its pastures. Clover, like the cow manure, feeds the soil with nitrogen directly, bypassing the chemical load of fertilizers.

Another way Clagett Farm tries to raise the best grass is through rotational grazing. This means the cows get a day’s ration of pasture each day, forcing them to eat all the different grasses in that piece of pasture. If the cows had more pasture, they would leave the types of grass they don’t like, and those grass types would spread and dominate the pasture.

The cows are moved daily, which takes some effort but makes for healthier grass and, thus, healthier cows.

And healthier cows lead to healthier beef eaters, extending the benefits to raising grass-fed beef beyond the environment to our grills and our families.

Raising grass-fed cattle changes the makeup of the beef.

“It’s leaner,” Heller says, “and low in Omega 6 fatty acids, which are found in grain and are not as healthy.” Not only is grass-fed beef low in the “bad” fats, it’s high in Omega 3 fatty acids and conjugated lineac acids (CLAs), which prevent cancer.

Grass-fed beef isn’t for everyone, though.

“Some would say it is less tender,” Heller says, “because it is considerably lower in fat.” But, he’s quick to add, “it does have plenty of flavor.” He advises marinating before cooking to increase tenderness.

“With my kids helping out on the farm, I don’t want to use pesticides and herbicides,” Heller says. “My goal is to raise a healthy family as well as healthy meat. And we all want to contribute to a healthy Bay.”

Where’s the Beef?

Most of Heller’s beef is spoken for by the staff and friends of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, but there’s plenty of fresh “clean” beef out there for your grill — both the healthier, environmentally friendly grass-fed beef and the more traditional local grain-finished beef.

Gibson, Dowell and Doepkins all sell beef directly to local butcher shops, where you and your neighbors can pick some out for a barbecue. Gibson, Doepkins and Heller also have customers who bypass the butcher shop, buying directly from the farmers. In other words, it’s not difficult to get local beef, and that means it’s easy to know the history of the hamburgers on your picnic table.

Buying local beef may well be better for your health; it also supports the farmers, whose jobs are also their homes, their memories — and some of our last open space.

Cow Fishing

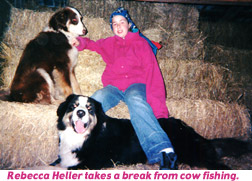

“I climb up into the hayloft above the cows,” says Rebecca, the 13-year-old daughter of Michael Heller, “and I take a piece of bailing twine and tie the end around a handful of hay. Then I go to the edge of the hayloft and hold onto the top of the bailing twine and drop the tied-on hay down to where the cows are. They all come over and I pull the hay up … and then drop it down again. They all stretch their necks up and open their mouths.

“Sometimes they’re too quick for me and they get the hay, or sometimes they get tired of trying and walk away. I’ve been doing it since I was six. I don’t even remember how I came up with the idea, but my dad thinks it’s really funny. I call it cow fishing.”

“Sometimes they’re too quick for me and they get the hay, or sometimes they get tired of trying and walk away. I’ve been doing it since I was six. I don’t even remember how I came up with the idea, but my dad thinks it’s really funny. I call it cow fishing.”

Farmer Mike supplements the cows’ meal when they can’t get a bite from Rebecca. However, unlike the cows, it’s up to meat eaters themselves to snatch up the opportunities for local beef that are dangling in front of us all.

See for yourself how a beef farm works at the Calvert County Farm Tour, July 20 from 1pm to 5pm. The farm tour includes three farms: Pin Oak Farm, 8855 Mackall Rd., St. Leonard; Spider Hall Farm, 3915 Hallowing Point Rd., Prince Frederick; and the beef farm, Eagles Ridge Ranch, 4970 Balls Graveyard Rd., Port Republic. Find details and directions in the farm tour ad in this issue.

Where’s the Beef ?

Where’s the Beef ?

Gibson has a bull, 22 cows and their calves. The deep red-brown color of his cows — along with several black coats, too — reveal that he has mostly Hereford cows, and a few black Angus. The calves are raised in pasture, but when they’re seven or eight months old and weigh about 600 pounds, they enter a feed lot to get ready for the slaughterhouse.

Gibson has a bull, 22 cows and their calves. The deep red-brown color of his cows — along with several black coats, too — reveal that he has mostly Hereford cows, and a few black Angus. The calves are raised in pasture, but when they’re seven or eight months old and weigh about 600 pounds, they enter a feed lot to get ready for the slaughterhouse. He has managed to keep his father’s Prince Frederick farm running and to support himself at the same time. But if you’re looking for a sign marking the Dowell’s farm as you drive by his land, you’ll miss it. The sign outside his driveway says Bryan Dowell, C.P.A. — that’s Certified Public Accountant.

He has managed to keep his father’s Prince Frederick farm running and to support himself at the same time. But if you’re looking for a sign marking the Dowell’s farm as you drive by his land, you’ll miss it. The sign outside his driveway says Bryan Dowell, C.P.A. — that’s Certified Public Accountant. Raising the herd on grass alone also allows the cows to do the work of synthetic fertilizers, diesel fuel and farm equipment. The cows fertilize the pasture with their manure and harvest their feed themselves.

Raising the herd on grass alone also allows the cows to do the work of synthetic fertilizers, diesel fuel and farm equipment. The cows fertilize the pasture with their manure and harvest their feed themselves. “Sometimes they’re too quick for me and they get the hay, or sometimes they get tired of trying and walk away. I’ve been doing it since I was six. I don’t even remember how I came up with the idea, but my dad thinks it’s really funny. I call it cow fishing.”

“Sometimes they’re too quick for me and they get the hay, or sometimes they get tired of trying and walk away. I’ve been doing it since I was six. I don’t even remember how I came up with the idea, but my dad thinks it’s really funny. I call it cow fishing.”