|

|

After 360 often contentious and sometimes bloody years living among Marylanders, native Piscataways will remember 2003 as a waymark in their trail of tears.

For the last quarter-century, Marylanders who know themselves as Piscataway Indians have sought recognition for their tribe. They’ve jumped hurdle after hurdle to document their lineage with Maryland tribal peoples — and in specific Maryland places — before 1790. In 2003, having presented all the evidence historians and genealogists could muster, the tribe waited for an official decision from Gov. Robert Ehrlich.

On September 24, Ehrlich announced that “The petition for recognition as a Maryland Indian tribe does not meet statutory requirements.”

A letter to the chair of the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs clarified the ruling. “This is not to say that some or many of the [Piscataway Conoy Tribe’s] members are not descended from Native Americans, however, the evidence submitted by the PCT does not support a degree of descent that is greater than would be found in the general population of the state.”

“Words can bring a people up or down,” said Chief Natalie Proctor of the Cedarville Band Wild Turkey Clan of the Piscataway tribe. Proctor leads one of several groups that joined to petition for state recognition of the Piscataway people as an American Indian tribe.

“Gov. Ehrlich seemed to be saying that our petition for recognition by the State of Maryland didn’t show that we were any more Indian than other Maryland citizens,” Proctor said. “I was devastated by his choice of words.”

Grace of God and Government

Across the country, native tribes have sought, and some have gained, recognition by state and federal governments. Federal recognition is a big deal, essentially returning to a tribe the sovereignty wrestled away by the expanding American nation. Recognition confers self-determination, and recognized tribes enjoy government-to-government relationships with federal agencies. In the West, many tribes made formal treaties and have lived for generations on recognized reservations with the power of self-government. Across the nation, 562 tribes have gained federal recognition, which also makes them eligible for a host of federal programs, including housing, education and transportation.

|

| Piscataway Conoy Chief Natalie Proctor and her husband Maurice at last spring’s Pow-Wow. |

State recognition is desirable, though not in ways so clear cut. It confers no new state benefits. It may open the door to limited federal benefits related to housing, health care, and education for minority groups, but it is not one of the criteria used by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in determining federal status.

From state to state, criteria for recognition differ widely. In South Carolina, for example, tribes must demonstrate historical presence for only the past 100 years. In Louisiana, a group can get state recognition simply by influencing a legislator to introduce a bill that the governor signs. In Connecticut, the colonial government itself kept detailed records of interaction with the Pequot tribe.

Maryland sets the bar higher. By state law, to gain Maryland recognition a tribe must prove through historic record its continuous identity with a Native American group that existed before 1790 and was indigenous to and inhabited a specific area in Maryland before that date.

Meeting Maryland’s standard sets a heavy burden of proof on the Piscataway, a tribe that historically depended on oral history rather than on a written language.

“The Piscataway didn’t record births or deaths in the way of European-Americans,” Proctor explains. “The tribe was matrilineal, so membership came through the mother, a very different pattern than the order of new American record-keeping. Children were said to be winter or spring babies. By the time of dispersal,” she says, “it was only by the grace of God that we survived at all.”

Nor did Maryland colonists make agreements for a Piscataway reservation. When Chief Turkey Tayak of the Piscataway Indian Nation died several decades ago, his group had to get state permission for burial in a traditional burial ground in Accokeek. Returning peoples had to buy their ancestral lands to pass them down.

So proving their lineage has been like hacking a trail through the wilderness. The first effort, in the mid 1970s, was sidetracked until the state could formulate criteria for recognition, which the legislature did in the 1980s. A formal petition was submitted in 1996, and the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs was persuaded that here were indeed Maryland’s own Piscataways. The appointed commission voted to extend official state recognition. That recommendation died on the desk of the cabinet secretary who oversees the commission.

|

| In a recent visit to America, the queen and king of Cameroon, center, met with Chief Natalie Proctor, right, and husband Maurice at the American Indian Cultural Center. |

The next time around, the tribe dug deeper into history. Aided by a lawyer familiar with establishing tribal identity and a historian who had helped Virginia tribes successfully document their claims, they searched state records, personal histories and even the archives of the Catholic Jesuit order to find more than two centuries of records showing direct ties to Maryland Piscataway prior to 1790.

This time, the legislature took up their cause. In spring of 2002, Del. Talmadge Branch — who says he descends from the Tuscarora Indians of North Carolina — persuaded the legislature to pass a bill giving the secretary of Housing and Community Development two months to act on the commission’s recommendation. The governor, in turn, would have four months. The bill passed by a vote of 128-7.

Amid questions as to whether recognition was part of an effort by Maryland tribes to open gambling casinos, as many tribes around the country have done, Gov. Parris Glendening — an implacable opponent of gambling — vetoed the bill.

In 2003, the Piscataway hoped a new governor — especially one unafraid of the reality of gambling, let alone its specter — would see their claim differently.

The Education of an Indian

Growing up in Southern Maryland in the 1960s and ’70s, Wild Turkey Clan Chief Natalie Proctor went to public schools, where she remembers that “to be an Indian was to be in the lowest category.” No one would admit to having even a smidgen of Indian blood.”

Searching for her own identity as a Piscataway, she helped form the non-profit American Indian Cultural Center, just north of Waldorf, run by the Cedarville Band. Now, the driving force in her life is educating other Americans about who Maryland Indian people were and are, their struggles and their closeness to the natural world.

Natalie and her husband, Maurice Proctor, helped create exhibits in the Cultural Center’s central building, including a longhouse, log canoe, art and artifacts. She encourages her people to express their own experiences as Indians in art and dance classes at the center. Since 1998, she’s organized the annual pow-wow, where all comers are invited to join in native dance and learn about native history.

|

| A Piscataway symbol marks the power of four directions. |

Visiting Washington, the king and queen of Cameroon made a diplomatic visit to indigenous people at the American Indian Cultural Center. Among Marylanders, it’s been educators, not government officials, who have seen the value of Piscataway history and traditions. Elementary schools bring children to see the longhouse, log canoe and exhibits of spearheads, shields and art. College professors like Michelle Simpson of the College of Southern Maryland send students to explore experiences of communication across cultures. Simpson’s students wrote down their notions of American Indians, then challenged their preconceptions after exploring the museum.

Misconceptions about Indians are many, Proctor says. Both children and adults picture Indians today doing the same things they’ve seen in books about the past. Do you live in teepees? they ask. No, says Proctor. “We used to live in longhouses, and now we live in regular houses just like you. We’re 21st century people,” she says, pointing to her computer.

The Piscataway, however, are 21st century people who can look at Maryland and know there was a time before the English colonies — perhaps as many as 10,000 years in this Chesapeake region — when their people gathered food, learned to live among black bears and mountain lions, told stories of their adventures, passed on wisdom to their children and cared for their elders. They shared a strong sense that humans are only one power among many in the great family that most Americans simply call the Earth but that the Indian peoples call Mother Earth.

People who claim Piscataway identity regularly gather at the American Indian Cultural Center. Next to the exhibit space is a large oblong meeting room where the Cedarville Band meets once a month to discuss and decide on common matters. The group organizes classes and supports contacts with other tribal peoples. Last year, a member created a children’s play based on the early encounters of Piscataway with English colonists. They elect their chiefs, volunteer for needed work and function as a tribal group. Their oral history is explicit about their tribal identity.

But that’s not enough for us modern-day descendants of colony and crown to give them official recognition.

Indians’ Maryland Wars

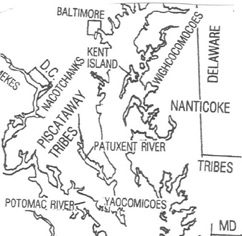

When Captain John Smith drew his Chesapeake map in 1612, he named native villages spread through Chesapeake Country, including Piscataway villages. Soon after, in 1634, Leonard Calvert and his land-hungry colonists arrived at St. Mary’s City, and they met with the chief of the Piscataway Confederacy to gain goodwill. The record kept by Jesuit Father Andrew White leaves no question about the existence of the tribe. That diary and other records show that the native peoples shared their knowledge about the seasons of shellfish and wildlife as well as about growing corn, beans and squash. Without that support, it is unlikely that the new Marylanders would have survived.

But peaceful coexistence soon ended. Paper rights from England trumped 10,000 years of living history among native peoples. Intent on claiming the land promised to them by the Lords Calvert and the King of England, colonists aggressively moved northward from St. Mary’s City. They fenced in their new properties, defended them and paid their taxes to the land-granting Calverts.

|

| Chief Natalie Proctor in the library at the American Indian Cultural Center. |

Only after the Revolutionary War would the new American federal government begin to make formal treaties with tribes farther north and west.

The native peoples of Southern Maryland — those who survived new diseases like smallpox and syphilis that arrived with the colonists — found it impossible to coexist with the settlers. Most moved farther and farther north and west to find places where they could hunt, fish and follow their traditions. That meant finding refuge among other established native cultures. Many groups either assimilated or vanished. Of all the Chesapeake-region tribes — the Yaocomico, the Patuxent, the Nanticoke, to name only a few — only the Piscataway have organized in sufficient numbers to seek recognition.

In addition to the group led by Natalie Proctor, there are two other gatherings of Piscataway peoples in Southern Maryland. Billy Red Wing Tayak leads the Piscataway Indian Nation; he has made a separate petition for recognition. Mervin Savoy, who leads the Piscataway Conoy, has been deeply involved in the petition for recognition just denied by Gov. Ehrlich as well as federal recognition from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was denied shortly before the governor’s decision and on the same grounds. To put forward a petition, an umbrella group, the Conoy Piscataway Confederacy and Sub-Tribes, was formed.

“I believe our purposes are the same,” says Proctor: “To bring forth a greater awareness of Maryland native people and the values we hold dear.”

Standing on the Rock

September 24 ended those hopes, at least for this round.

Gov. Ehrlich’s decision doesn’t, however, mean that the Piscataway will stop being Piscataway.

Proctor has just turned 45. To help express her new sense of identity, she prayed for a new name. “My first Indian name was Wandering Cloud, because I’m a big dreamer,” Proctor says. Living with a foot in each of two worlds — the Native traditions and the 21st century America — provokes dreams of how the two can be connected.

Her new name as chief is Standing on the Rock.

Like the rock of tradition that she stands on, she says she’s in for the long term. “My focus is now on the generations to come and their spiritual and economic needs,” she says.

Regaining her tribe’s lost identity is another part of her dream. “It’s not good for government officials to keep only a long-distance relationship with the indigenous people of the region,” Proctor says. “I want that to change.”

That change will take new approaches to recognition on the Piscataways’ part. Gov. Ehrlich’s announcement says he is open-minded, but only if “they identify additional evidence sufficient to answer outstanding questions” about blood lines.

So the quest begins anew.

“Everything an Indian does is in a circle,” said Western Lakota wise man Black Elk. “That is because the power of the world always works in circles.”

Piscataway have circled back to home in Maryland.

What About Casinos? What About Casinos?

Recognition means casinos in Maryland. That’s a common perception, fed by speculation that there’s no other reason the Piscataway would be asking for tribal recognition at this point of history.

In fact, neither state nor federal recognition of an Indian nation is a slippery slope to casino ownership. Of 500 federally recognized tribes, only 200 — divided among 28 states — are “gaming tribes.” North Carolina has one gaming tribe, The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. New York has three. Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Ohio have no gaming tribes.

Nor would the Piscataways be among the gaming tribes. Under federal law, they couldn’t be. The federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act sets two criteria to open a casino: both federal recognition and “the powers of self-government” that come with tribal ownership of reservation land.

Maryland Piscataway groups meet neither criteria.

Federal recognition had been denied by the Bureau of Indian Affairs before Ehrlich made his decision.

The Cedarville Piscataway are on no casino quest, according to Chief Natalie Proctor. “American culture seems to be so driven by money that it’s hard for many people to see that ‘prosperity’ could mean anything other than more money,” Proctor says. “Recognition is not about the right to have a casino.”

Walk in Indian Moccasins

Think of all the times you’ve checked Caucasian or Asian or African American or Hispanic on some official form tracking ethnic backgrounds. Then imagine someone writing back to say that, to count yourself in that group, you needed to show written evidence that your ancestors before 1790 were members of the group you claim. What’s more, you must be able to clearly track the connecting generations between those ancestors and yourself.

No matter what our group identification, most of us would come up blank. Our parents and grandparents tell us our ancestry. That’s how we know who we are.

About the Author:

Sara Ebenreck, a former philosophy teacher at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, is project director for Chestory: The Center for the Chesapeake Story. Her last story for Bay Weekly was last week’s ‘Growing St. Leonard ~ A Community with a Past Tries for a Future.’ |

|

|

|