|

|

|

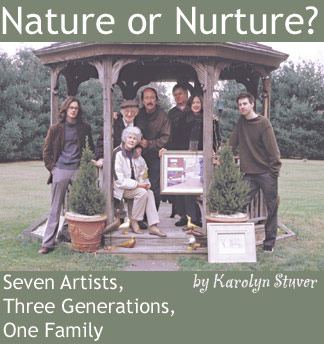

Three generations, opposite from left to right, Brinton Jaecks, Earl and Mary Brinton, John C. Brinton, Harry Jaecks, Jean Brinton Jaecks and Andrew Jaecks. |

Love your family. Work hard. Indulge your passion to create. That’s what Severn natives Jean and John Brinton learned from their parents, Mary and Earl. Harry Jaecks, another local from Glen Burnie, grew up with the same basic principles. After he and Jean married and had kids, the couple brought their boys up according to the same principles. Jean’s brother John is following suit with his family, a wife and daughter, on the Eastern Shore.

Family is the first priority in the Brinton-Jaecks clan. That’s one reason they’ve all remained in the area. But in a bloodline where nearly everyone is involved in art one way or another, there are no hard dividers between family life and their lives as artists.

In January, works by seven members of the clan will be part of a multi-generational exhibit at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts. The variety of the work on display — including portrait photography, oil and egg tempera paintings, wood carvings, sculpture and multi-media — showcase the breadth of talent resident in the Brinton-Jaecks DNA. At the same time, you’ll get to do something rare: see evolving values and family traditions at work.

The First Generation The First Generation

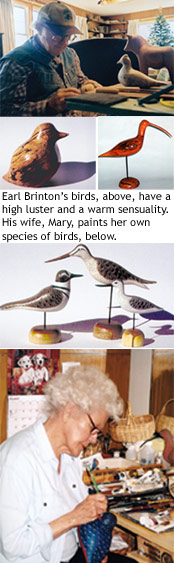

Earl Brinton cradles a plump bird in his right palm. A few strokes of his left thumb emphasize the grain of the wood. You want to reach out for the piece, which is the reaction he wants. Brinton Birds, as his signature sculptures are known among collectors, have a high luster and a warm sensuality that begs to be held. “Early on I made too many skinny birds,” says Earl of his birds, based on a partridge. “People kept saying ‘make chubby birds.’ Once I started to fatten them up, they became more of a success.”

Adds wife Mary, “They have character; it just seems like they do.”

Shape may contribute to the character of Earl’s birds (he sculpts a variety of fowl, in addition to his trademark pieces), but it’s only one reason they have received attention from collectors as well as the National Wildlife Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian Institution and the Audubon Society and others. Mary says it’s also the way he coaxes “the spirit from the wood,” using the grain to achieve specific features. This power transforms the carving into sculpture, the point at which craft becomes art.

Carving is Earl’s second career, which he’s been at for a quarter century. Now in his 80s, he’s also been a woodworker, a foundry worker and a crafter of aircraft tools. He and Mary, also in her 80s, live in Severn, six miles from their daughter and son-in-law.

There, Mary paints shorebird carvings that Earl sculpts especially for her. She works in an upstairs bedroom that overlooks a quiet street and characterizes her time there as therapeutic.

“When I’m up here,” she says, “I am just so focused and absorbed. I don’t have a worry in the world. Problems just melt away.” She describes her work as accurate, yet stylized rather than true to life, and “reminiscent of early decoys that hunters painted with house paint or whatever they had laying around.”

Mary’s career as an artist started humbly enough. On weekends, the family went to craft shows, where Earl sold his sculptures. Mary found the painted decoys interesting and thought she’d like to try it. She taught herself how to paint, developed her own style and began offering her birds at craft shows and exhibitions up and down the East Coast right along with Earl’s. Today Mary’s pieces have earned a following of their own.

Her work area is so tidy it could be mistaken for a sewing room instead of a painter’s studio, a sharp contrast to the organized chaos of Earl’s large basement workshop. Here piles of dried wood are neatly stacked and sorted, filling nearly every crevice, and it’s overwhelming to the uninitiated. Earl points out the assorted floor-mounted sanders and explains the purpose of each. He shows off a dizzying number of special carving tools carefully stored and maintained on workbenches lining the walls, as well as a fascinating vacuum system he’s rigged for collecting dust. As a former toolmaker, Earl has made or customized many of the implements.

Until Earl’s retirement, art was a hobby for the Brintons. However, he and Mary managed to make it integral to family life.

“We wanted to do something all together,” Mary explains. “We went beach combing and picked up stones. Earl made a tumbler out of an old bucket lined with rubber and we polished those stones. To us, we thought these were pieces of art, semi-precious stones, almost. We studied the stones as a family and loved their natural beauty. And that’s how we all got started. Loving nature and nature’s beauty.”

In addition to the art projects and craft shows — which eventually led to larger exhibit venues for Earl and Mary, including the annual Waterfowl Festival in Easton — the family maintained an organic garden at home and made frequent trips to museums. Over the years, this way of life turned into a system for nurturing family-minded, hard-working artists.

The Second Generation

“My parents’ most significant influence on me was their work ethic,” says John, the eldest of the two Brinton children. “Dad worked in the aerospace industry, but he always had another gig. He was always involved in wood. That evolved into wood carving and sculptures, which led to the birth of the Brinton Bird, and he has really built that into something.”

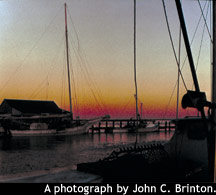

John Brinton, a grants manager for a government agency who has both a business degree and graduate work to his credit, learned to balance work and family with his passion to create. But he didn’t take to carving or painting. Luckily, his father flirted with photography and it was this — the concept of framing perspective on film — that fired John’s interest. Now in his 50s, John has been a professional portrait and landscape photographer for 30 years. John Brinton, a grants manager for a government agency who has both a business degree and graduate work to his credit, learned to balance work and family with his passion to create. But he didn’t take to carving or painting. Luckily, his father flirted with photography and it was this — the concept of framing perspective on film — that fired John’s interest. Now in his 50s, John has been a professional portrait and landscape photographer for 30 years.

“Making an incredible connection with the subject is what I like best about portrait photography,” he explains. “My goal is to put the person at ease and photograph them in an extremely natural way.” The final portrait “has an energy in it,” he says.

In the years since he trained as an army combat photographer, Brinton has transformed his craft to an ideology.

“So much of my work is based on my love of the outdoors. I’m a naturalist. I live very simply and try to be as much a part of the natural world as possible.” He describes his lifestyle as “almost crude,” living in an old farmhouse on the edge of the Pocomoke Forest in Somerset County. “We moved down here as an experiment, but within six months we fell in love with it.”

He says the family eschews many amenities some people can’t live without: cable TV and heat upstairs, for example. “It’s a very simple life,” he reiterates.

This translates to his straightforward Eastern Shore lifescapes, where the artist lets the unvarnished, non- sentimental truth of the scene be its own message.

Even with the Brinton work ethic, John admits that balancing a family and two professions can be overwhelming. His saving grace, he claims, is tai chi, which he teaches as well as practices.

“That centers me,” he says. “It gives me peace and incredible focus plus good physical strength. It also helps that I’m a time management geek.”

Generation One, Part Two

On their first date, Harry Jaecks took Jean Brinton to paint pictures of an old stone house on Burns Crossing Road. “I still have mine,” Jean chides, “but Harry sold his.”

Piping up in his own defense, Harry says, “I had a collector who bought quite a number of my old pieces. That was one of the first pieces he bought.”

Cash beat sentiment that time, but spend an afternoon with Jean and Harry, and you see that family and growing together as artists are what motivate them. During a visit to the couple’s Millersville home and studios, they were getting ready for not one but two exhibitions and had stacked finished canvases throughout the house. Cash beat sentiment that time, but spend an afternoon with Jean and Harry, and you see that family and growing together as artists are what motivate them. During a visit to the couple’s Millersville home and studios, they were getting ready for not one but two exhibitions and had stacked finished canvases throughout the house.

“We were told — ‘two artists in the same household, forget it, it will never last,’” recalls Harry. “But it’s been the great strength of our marriage.” People predicted the two wouldn’t be together longer than two years, but the Jaecks say they’re still going strong after nearly 28 years. Jean credits art as a common reference point and her parents as good role models.

“Just look at them,” she says. “They are so supportive of one another. They’ve been together almost 62 years.”

This husband and wife’s media differ. Jean prefers watercolor and oil, while Harry says egg tempera (which in family harmony Jean teaches) better suits him. He also works in pencil, watercolor and drypoint. But both paint nature, directly or indirectly, in relationship with day-to-day life.

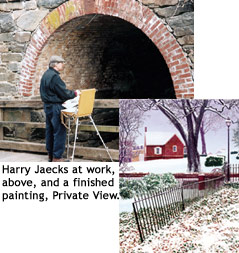

“The thing that really inspires me is atmosphere and architecture, atmosphere and light,” Harry says. “Anything that looks as if it was crafted by hand. That could be an old corn crib, a pusher boat on the stern of a skipjack, things crafted from wood.”

Many of Harry’s landscapes are of the documentary stripe. “I am recording a way of life,” he says. “And in many cases, it’s a way of life that is disappearing. Both Jean and I have been painting the Chesapeake for 30 years and have watched it change so much over that time. It’s like we’re making a study of the Bay.”

The couple, in their 50s, feel compelled to pursue their study from what they call an “unusual perspective.” For Jean, that may mean exploring color shifts among native flora within one of Annapolis’ public gardens. For Harry, that might translate into a back-alley view of a little-known historical building.

Harry is a graphic designer by day, but once, when he was younger, he considered becoming an architect. This explains not only his fascination with hand-built things but also his obsession with fine details. That obsession makes viewing his paintings a multi-sensory experience, allowing you to feel the cold snow and hear it crunch in a winter scene, or, in another, hear the autumn leaves rustle in the wind.

Like his brother-in-law, Harry presents a straightforward perspective. Life around the water can be, he says, “a very dirty and hard life. It’s not always pretty. I want to convey that in my work rather than idealizing it. There’s plenty about life here, around the waterfront that is beautiful and exquisite but there’s also a lot that’s gritty and so painfully ordinary. That’s what’s most interesting to me.”

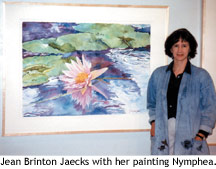

Jean is a full-time artist. She also teaches at St. John’s College and conducts classes at the U.S. Botanic Gardens, the U.S. Arboretum and at various Annapolis gardens. Having studied under famed impressionist Henry Hensche, she developed a style of using color blocks to create light and form. Her philosophy is less documentary than her husband’s and closer to the fundamentals she grew up with. Jean is a full-time artist. She also teaches at St. John’s College and conducts classes at the U.S. Botanic Gardens, the U.S. Arboretum and at various Annapolis gardens. Having studied under famed impressionist Henry Hensche, she developed a style of using color blocks to create light and form. Her philosophy is less documentary than her husband’s and closer to the fundamentals she grew up with.

“I like to take the simple and mundane, the things in life that you might pass by everyday and call attention to it,” she says. “I want people to stop and look and see the beauty they might not have noticed before.”

Jean says her work is about revealing, which she explains is actually a very complex concept. “I don’t want people to say I love the grapes or the pear Jean painted — but the light on it. Or maybe the texture. I want to take those times when the light is just right and use that to draw your attention or to illuminate a certain quality, to create atmosphere and mood around an object, to give it an aura.”

It’s probably fair to say that none of the artists in the first two generations are motivated by an ideological agenda. In fact, the eldest Brinton dismisses the prospect. “I’m sort of an apolitical person. It doesn’t influence my work at all. I think there’s too much of that,” he says.

In the succeeding generation, however, political angst appears.

The Third Generation

With two generations of artists ahead of them, the Jaecks siblings, Andrew, 26, and Brinton, 24, grew up immersed a layer deeper in the family values than did their mother and uncle. In what sounds like a case of ancestral déjà vu, Andrew recalls going to museums with his parents as a seminal influence. “From the time we were little we went to museums,” he says. “It was a very big part of family life, and it made a big impression on us.” With two generations of artists ahead of them, the Jaecks siblings, Andrew, 26, and Brinton, 24, grew up immersed a layer deeper in the family values than did their mother and uncle. In what sounds like a case of ancestral déjà vu, Andrew recalls going to museums with his parents as a seminal influence. “From the time we were little we went to museums,” he says. “It was a very big part of family life, and it made a big impression on us.”

He was raised, he believes, to be an artist, but says he and his brother felt no pressure to follow any particular path or in anyone’s footsteps: “Being around art our whole lives, it’s been very natural for us to go ahead and pursue art in our own ways.”

The weekends spent in their granddad’s basement learning how to carve also shaped both grandchildren.

“Most of the family influence that we’ve had is probably more on the craft side than on the conceptual side,” says Brinton. “The work ethic, the medium, the tools. That sort of thing.”

Their grandfather’s basement studio in Millersville remains their primary woodworking space, and one or both of them can be found there most weekends and many free evenings. Their grandparents offer support and advice — when solicited — plus food, of course.

Both Andrew and Brinton sculpt in wood, but their work also incorporates computer graphics and other multi-media elements. The results are products a far cry from the more traditional pieces produced by the rest of the family.

“All of my work tends to be socially or politically influenced,” Andrew says. “Probably the most common theme I deal with is conflict between the artificial and the natural. Today, everything is computerized and mechanized. We’re a part of nature, organic, imperfect by design. I believe trying to integrate these two worlds creates tension and is a significant cause of many of our social problems. That’s what my sculptures in the [upcoming] exhibition are trying to capture.”

Brinton’s artwork, on the other hand, is more clearly within the family tradition. He has carved delicate wood flowers for the exhibition that appear to be an homage to both his mother’s garden paintings and his grandfather’s sculptures. Brinton’s artwork, on the other hand, is more clearly within the family tradition. He has carved delicate wood flowers for the exhibition that appear to be an homage to both his mother’s garden paintings and his grandfather’s sculptures.

The more significant piece Brinton is showing is a series of wood sculptures incorporating shadow and light called “Epistemology by Birthright.” It’s meant to represent, according to the young artist, “how other cultures perceive America — the U.S. martial image.” Not surprisingly, the war in Iraq was his major inspiration.

True to their Brinton-Jaecks stock, neither brother can be accused of slacking. Brinton is an award-winning animator who works full-time at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, where both he and Andrew earned degrees in art. There he develops computer animation and special effects projects for clients of the University’s Image Research Center. His elder brother plays bagpipes in two bands and works full-time at National Geographic as an imaging technician.

For now, family and local ties are enough to keep Andrew, an Annapolis resident, close to home, but Brinton, who lives in Baltimore, is considering graduate school. He may be the first of the relations to leave Chesapeake Country. If that happens, it will be rough on everyone. But that’s a future worry for the Brinton-Jaecks. Now, there’s a show to get ready for. There’s work to be done.

Three Generations of Chesapeake Artists: 9am-5pm Mon.-Sat. January 9 through February 13 at Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts’ Chaney Gallery, 801 Chase Street Annapolis: 410/263-5544.

About the Author:

Karolyn Stuver is a freelance writer based in Alexandria, Virginia, and a sailor out of Deale. Highlights in her 20-year career include stints in broadcast and print journalism, corporate communications and on Capital Hill as a political aide. |

|

|

|