Volume XVII, Issue 38 # September 17 - September 23, 2009 |

|

|

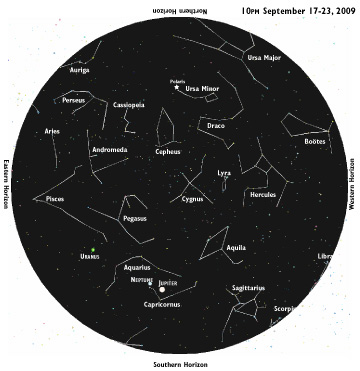

Sky Watch

Sky Watch

by J. Alex Knoll

Equal Night

Equinox has long been more than a celestial event marking the changing seasons

Tuesday the 22nd marks autumnal equinox, the first day of fall. Since summer solstice in June, our days have grown ever shorter; now until winter solstice, the sun will shine lower and lower on the horizon, providing less and less sunlight.

Meaning equal night, equinox marks the point at which night and day are the same length. On two days of the year — the vernal and the autumnal equinoxes — the center of the sun passes directly over the earth’s equator, shedding equal light on both the northern and southern hemisphere.

Meaning equal night, equinox marks the point at which night and day are the same length. On two days of the year — the vernal and the autumnal equinoxes — the center of the sun passes directly over the earth’s equator, shedding equal light on both the northern and southern hemisphere.

Throughout history, civilizations have marked the equinoxes as special. The ancient Greeks marked the autumnal equinox with the Feast of Dionysus, a raucous celebration in honor of the two-faced god of wine. In Great Britain, long before even the Celts, unknown peoples built stone circles, most notably Stonehenge, to mark the equinoxes and solstices.

America has its own Stonehenge, a 4,000-year-old site in New Hampshire, believed to be built by either Native Americans or unknown early European explorers. The site contains six stones — although one has fallen — aligned to sunrise and sunset at the equinoxes.

In the British Isles before the spread of Christianity, the Celts celebrated Mabon, the second harvest, by burning a woven sacrificial figure representing the plant spirit. This celebration has been reborn as the week-long Burning Man Project in the Nevada desert.

The Catholic church co-opted such pagan celebrations with its own holidays, in this case Michaelmas, celebrated on September 29. Special loaves were baked in honor of the archangel Michael, and the lords collected their taxes from the peasants who worked their lands.

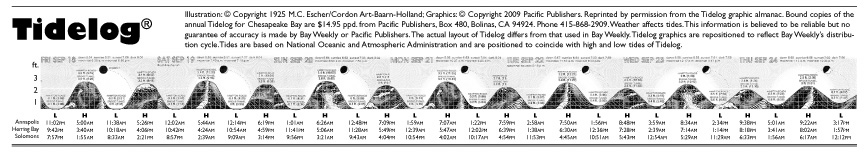

Illustration: © Copyright 1925 M.C. Escher/Cordon Art-Baarn-Holland; Graphics: © Copyright 2009 Pacific Publishers. Reprinted by permission from the Tidelog graphic almanac. Bound copies of the annual Tidelog for Chesapeake Bay are $14.95 ppd. from Pacific Publishers, Box 480, Bolinas, CA 94924. Phone 415-868-2909. Weather affects tides. This information is believed to be reliable but no guarantee of accuracy is made by Bay Weekly or Pacific Publishers. The actual layout of Tidelog differs from that used in Bay Weekly. Tidelog graphics are repositioned to reflect Bay Weekly’s distribution cycle.Tides are based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and are positioned to coincide with high and low tides of Tidelog.