NBT Interview:

Maryland's Poet Laureate

From Potatoes to Poetry, Roland Flint Digs

into America

with Sandra Martin

Maryland still has its anchor planted

in the England Will Shakespeare knew, which explains why our state sport

is jousting -  rather than lacrosse - and why we have a poet laureate. Just as

knights on horseback used to run at each other with lances drawn, so did

poets run around the land singing their songs. Just as the knight who fought

to victory won the prize, so did the poet who struck the right chord. The

poet's prize was a laurel wreath to be worn like a hat or halo and evergreen

to signify the immortality of inspired song.

rather than lacrosse - and why we have a poet laureate. Just as

knights on horseback used to run at each other with lances drawn, so did

poets run around the land singing their songs. Just as the knight who fought

to victory won the prize, so did the poet who struck the right chord. The

poet's prize was a laurel wreath to be worn like a hat or halo and evergreen

to signify the immortality of inspired song.

In fact, life without poetry must have been less livable

than life without jousts, for the custom of wreathing a poet goes back millennia

rather than just centuries, to the artistic Olympics of golden Greece. From

there the poet laureate evolved into an office holder, appointed to serve

a realm and sing its praises. According to the storyteller John Barth -

who holds unofficial standing as Maryland's reigning novelist - an aspiring

poet laureate was one of Maryland's early colonists, enduring storms, shipwreck

and savagery for the sake of his art. Perhaps Barth's A Voyage to Maryland

and Ebenezer Cook's role in Maryland history may not be entirely factual.

Nevertheless, Maryland our Maryland does indeed have its poet laureate -

has since 1959.

Poet laureates come one at a time, appointed by the

governor to a three-year term. They earn no money but lots of honor, in

the job of going forth throughout the state to promote poetry by bringing

it to the people.

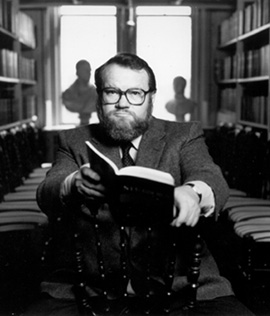

Since 1995, Maryland's poet laureate has been Roland

Flint, 62, of Silver Spring. He's practiced his craft since he returned

to college as a young man of 22 who exchanged a lieutenant's commission

in the U.S. Marines in the waning days of the Korean conflict for a seat

in the University of North Dakota's entering class of 1956. For 40 years,

he's also taught writing and literature, retiring this year after 29 years

at Georgetown University.

As a boy weathering the Great Depression in North Dakota's

farm country, Roland Flint got plenty of that state's black dirt on his

hands. "A mixed Celt," he calls himself in a poem, and this stocky,

ruddy man is easy to imagine as a farmer or perhaps a flinty Scot. Yet he's

chosen what another poet, Robert Frost, called "the road less traveled

by."

To judge from Flint's poetry, that road is not so very

different from yours and mine, with all the usual stops for love and loss

and eating a meal with a friend or finding a lost child or buying a flower

- except perhaps in one way. Flint has stayed with his experience, rolling

it over in words until he could give it a name.

Q As poet laureate, you are surely Maryland's

authority on poetry. Let me appeal to your authority to explain to NBT readers

what relevance poetry has to their lives.

A In times of need, whether

great or small, for whatever kind of inspiration, people who seem to be

distant turn to it for common feelings captured in uncommon language.

Poetry is a quick way to the sources of the spirit. As a wonderful poet,

William Matthews, says in his last poem, "it's not about beauty but

about passion and accuracy."

And as the poet James Wright says, that no matter how it seems to be

ignored, poetry goes on making a kind of archive of the country's spirit.

Q What do you do as poet laureate?

A I haven't written any official

poems and with any luck, I won't have to. That's not a part of the tradition

in America.

Poet laureate is a non-paying position, and when I was asked what I would

be willing to do, I said I was unwilling to go places I had to convert people

to poetry. I wanted to speak and read to audiences who were really interested.

I was willing to go to any public institution that normally could not

afford such a program: public schools, retirement homes, prisons. The governor

wanted to emphasize youth, so I have almost exclusively gone to public high

schools. Maryland has 24 counties, and I've been now to more than half.

This month I go to two, next month I visit three. Last month I went to Calvert,

Charles and St. Mary's High Schools.

Q Your poems remind me of Robert Frost's

in that you seem to be talking of things any of us might understand and

doing so in language we might use.

A That's important to me.

The poet Stanley Kunitz, who won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry a couple

of years ago, said "I dream of an art so transparent that you look

through and see the world." That doesn't mean there's not an art to

it, but I hope also there's simplicity and clarity of language.

Q Why do you think you were selected as

Maryland's sixth poet laureate?

A One thing that might be

part of it is that my poems are accessible at the first level of understanding.

They're user friendly.

Q What do your young audiences think of

poetry?

A Their response depends

on their exposure, how prepared or engaged they are, and what kinds of teachers

they've had. In general, it's a lot of fun. In most cases, they really are

interested. The best situation for me is when teachers have given them my

poems ahead of time. That makes them more engaged and involved with more

questions to ask.

Q What do they want to know?

A What I usually do is read

30 to 40 minutes from my poems and the poems of others, and then we talk.

They have a great variety of questions. They're interested in nuts and bolts

things, when, why and how did you become a poet, when did you publish first,

what's your work day like, plus things like how are poems that don't rhyme

really poems.

It is hot today, dry enough for cutting grain,

And I'm drifting back to North Dakota

Where butterflies are all gone brown with wheat dust.

And where some boy,

Red-faced, sweating, chafed,

Too young to be dying this way,

Steers a laborious, self-propelled combine

Dreaming of cities, and blizzards -

And airplanes.

With the white silk scarf of his sleeves

He shines and shines his goggles,

He checks his meters, checks his flaps,

Screams contact at his dreamless father.

He pulls back the stick,

Engines roaring.

And hurtles into the sun.

Q Many of your poems take us back to your

own youth. Tell us about your family background

A I was a farm boy, one of

six with three brothers.

My dad had a farm but lost it in the Depression. I was born in 1934.

The Depression came late to North Dakota, but we were in it then. After

he lost the farm, he worked as foreman on farms owned by others, growing

grain and potatoes, wheat, corn and sugar beets - but mostly potatoes. My

home county, Walsh, is second only to Aroostook County in Maine in total

potato production.

I've worked as a laborer in potatoes. In those days it was mostly diggers

that did two rows at a time, then pickers picked and dumped the potatoes

into bushels, then truckers came into the sack rows. Similarly on the other

end, the potatoes were trucked and unloaded onto conveyors that took them

to warehouses where they were graded for quality. I worked in almost all

of those jobs.

Q You describe yourself in a poem on your

parents as "their odd son," and such lines in your poems as "I

could have died many times from carelessness or experimenting" make

you seem to have been a bit wild. Was that the poet in you coming out at

an early age?

A I was only comparatively

wild, but whatever it was had settled down by college and I became for the

first time in my life, a serious student and got very good grades and was

writing all the time. While working on my doctoral degree at the University

of Minnesota I married and had three kids fast. That tends to sober one.

I didn't start to write until the university. I had flunked out, started

in the Marine Corps and Korea, then got back in school and began first being

interested in poetry and then trying to imitate the poets. I had some very

good teachers at University of North Dakota.

I tried to write a love poem in sonnet form and my professor couldn't

resist laughing, but that did not stop me. I was hooked pretty good. I never

stopped, though sometimes when I got rejection slips I would say I would.

QWas your life in the Marines a step on

the road to poetry?

A I liked the Corps, I knew

all about rigid discipline from my dad, I was young and strong enough that

physical stuff didn't bother me and my dad was not there so I didn't need

to be mad at him.

I was in Korea after the fighting. I left as a corporal after two years

You could get early release if you demonstrated you had been accepted at

a college. I made up my mind on Christmas night in Korea on guard duty at

an ammunition dump. I had this illumination I should be in college ...

Q Many Marylanders know, by way of John

Barth, how Ebenezer Cook set his cap becoming poet laureate back in the

18th century. Did you, too, dream of becoming poet laureate?

A No, I was approached. The

retiring poet laureate, Linda Pastan, had been on a committee to name a

successor and asked if I would take it, and I said I would. Then it became

official.

The poet laureateship of states varies considerably. What gives it distinction

in Maryland is the people who precede me. Maria Coker, Vincent Godfrey Burns,

Lucille Clifton, Reed Whittemore and Linda Pastan are all nationally known,

excellent poets, and I'm grateful to come after them. That, plus the seriousness

with which Governor and Mrs. Glendening took [the appointment and installation

ceremony in 1995] gives me pleasure.

It's fall but he's written his fall poems,

his harvest poems and here comes age poems.

Few have noticed, but he's tried everything,

including birth life and death poems,

the dying Christ, the death of God,

the ministry of work poems ...

his father, grandmother Rose and others.

Himself he's covered like a wall, poster-full.

He's even tried Alaska and Korea,

Bulgaria and Iwo Jima (no visit required).

So now he's trying to wait ...

But something stubborn wants him scribbling daily,

even if it is the only thing to write about.

Like straw blown through a tree, it's in him ...

At his swearing in ceremony, Roland Flint read the poem "Prayer,"

or which he presents a copy to Gov. & Mrs. Glendening, below.

Q Let's talk a bit about the force of

poetry in your own life. W hy

do you write?

hy

do you write?

A It just seems to be necessary,

something I'm supposed to do and have to do. I try to write a little every

day and keep a journal, and I work on poems, new or not so new.

I know when I haven't honored my contract, done what I'm supposed to

do, and I feel a kind of uneasiness or lack of coherence.

Q What do you write about?

A My subjects usually come

from what poet John Crowe Ransom called "common actuals," that

is, daily experience.

Q Do you get clarity about a subject from

writing about it?

A Clarity and resolution,

yes, sometimes that happens. Things that I can't make peace with otherwise

I do by writing about.

Q How do you write?

A I still use a spiral notebook

to begin but very quickly I get in the computer. I'm very computer dependent.

Now they're all in the computer. For many years I actually kept copies -

and lots of embarrassing drafts that got nowhere.

Q How many poems have you written in the

40 or so years you've been a poet?

A Oh my God, I don't know

... six or seven books. My first book [And Morning, 1975] was only 29 poems,

and by then I published twice that number in magazines and a whole lot more

never got into magazines.

Q How well do books of poems sell?

A Stubborn [1990] sold almost

2,000 copies total, and that's including a second printing,

Wallace Stevens' first book, Harmonium, is considered a cultural landmark,

and it first sold 300 copies. Kurt Vonnegut, the icon, wrote poems first,

and when his first poem was accepted he received a check for $2. He says

that's when he switched to fiction.

Q Has the World Wide Web changed the way

poetry reaches people?

A I've never downloaded my

poetry or anyone else's, but I know those who do. I still read a lot of

poetry magazines and journals as well as books, and I've just heard by email

from a Salvadoran poet I know who translated "Prayer" and wants

to translate others.

Q Could you have made a living as a poet

had you not been a teacher, too?

A My writing career has sort

of dovetailed into teaching. Could I have done it if I had set out to? Some

do, but not many. I've never advertised or tried to get readings, so I don't

know. The odds are not good, given the public record.

Q You retired this year?

A I taught at Georgetown

University 29 years, and I was ready to leave. I was not tired of teaching,

but I was ready to retire. A colleague and friend of mine died when he was

65, rather abruptly, and that made me think of all the things I wanted to

do.

Q What are those things you want to do

now that you've retired?

A Reading, writing, traveling

Q And your family?

A I'm close to my grown-up

children, two daughters, 32 and 34, and two stepsons, 35 and 30. I lost

a son in an accident. There are no grandchildren yet. I'm married to my

second wife, Rosalind Cowie, who works for the General Accounting Office

in the training department, though she has her Ph.D. in modern literature.

Q You told me that you and your wife were

both glad to get out of the middle of the country when you left Minnesota

30 years ago. How have you liked Maryland?

A I like life in Maryland

very much, and I've seen a good bit going round to these schools and the

many colleges I've read at. It's beautiful.

Q What advice do you have for readers

who might dream of becoming poets?

A I'd advise them to immerse

themselves in whatever discipline they're interested in perfecting. Almost

all the poets I know are great readers of poetry.

Q Have you liked this wordy life you've

made for yourself?

A Yes. I can imagine other

ones, but I love being part of it.

I'm still in touch with lots of students by email and I was not burned

out by teaching. I enjoyed my last year very much, and I love my association

with other writers.

Q Where can we read more of your poetry?

A Three books are still in

print and most bookstores will order them. Stubborn is available from University

of Illinois Press; Pigeon from North Carolina Wesleyan College Press; and

my second book, Say It from Maryland publisher Dryad in Tacoma Park.

I'll have a new book, Easy, out a year from now. It's about how poetry

ain't ...

Editor's note: sample Roland Flint's poetry on the worldwide web by

using the search engine Alta Vista and typing +"rolandflint"

Q Mr. Laureate, what parting words do

you have for our readers this poetry month?

A Read poems. And if it's

not immodest, my poems.

What I Have Tried to Say to You

That there are ways to love the life you haven't had,

ways to forgive the one you have ...

| Back to Archives |

Volume VI Number 15

April 16-22, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |

rather than lacrosse - and why we have a poet laureate. Just as

knights on horseback used to run at each other with lances drawn, so did

poets run around the land singing their songs. Just as the knight who fought

to victory won the prize, so did the poet who struck the right chord. The

poet's prize was a laurel wreath to be worn like a hat or halo and evergreen

to signify the immortality of inspired song.

rather than lacrosse - and why we have a poet laureate. Just as

knights on horseback used to run at each other with lances drawn, so did

poets run around the land singing their songs. Just as the knight who fought

to victory won the prize, so did the poet who struck the right chord. The

poet's prize was a laurel wreath to be worn like a hat or halo and evergreen

to signify the immortality of inspired song. hy

do you write?

hy

do you write?