the Big

the Big the Big

the Big

the Bad

and the Ugly

Your Armchair Guide to Chesapeake Bay's Underwater Oddities

by

Sandra Martin

by

Sandra Martin

Just sitting on the Dock of the Bay, watching the tide roll away, sitting on the Dock of the Bay, wasting time

Practicing what soul singer Otis Redding preaches has shown many a Bay sitter more than the tide.

It was on just such a June day as this that, sitting on a dock of the Bay, I discovered we are not alone.

The Bay's silver screen suddenly rippled with life. Wings pierced its limpid surface. Dozens of flat bodies, stacked in shifting layers, glided, soared and gyred. They flapped, cruised, chased, leapt and banged into one another.

What I saw was the summer mating dance of stingrays. Every June, into the Bay from southern Atlantic waters swim flotillas of these strange flapping kites with whip-like tails, radar-like sensors and voracious appetites for shellfish. These Rhinopterae, familiarly known as cownose rays, graze the Bay all summer long, mating and giving birth.

Rays are but one of a cast of characters as fantastic as any you might encounter in a Star Wars cantina. Chesapeake waters team with feats of nature's imagination. To see them for yourself, you don't have to travel to another planet; you only have to get out on the water. When you wet your line, cast your net, launch your boat or dive right in, here's a glimpse of what you'll see. What you can see there, you may never see the likes of again.

The Big

Chesapeake's annual rays may not be the biggest fish in the Bay, but they're big enough that if one is swimming alongside you, you'd notice. A ray spreads up to 70 pounds of fish into a flat disk propelled by a pair of horizontal pectoral fins. A big one can reach seven feet, but more common are wingspreads of three to five feet.

It's the tips of those wings - and the boil of water around them - that give rays away to watchers on the dock of the Bay. Rays are also familiar to windsurfers, and we've heard one credit rays with a dolphin-like curiosity, claiming they follow just for fun. Divers sometimes court their company, using treats to invite close encounters.

"I sit quietly on the bottom, enjoying the acrobatic maneuvers of these graceful creatures. Small rays sail around me, seeking bits of food. A small ray's bump is no bother, but if Ma or Pa happens along, it's more thump than bump," related long-time Chesapeake diver John Rue.

Anglers are less happy to encounter a ray. "It feels like a '57

Chevy attached to the other end," says one fisherman. Many cut their

lines when they feel the heavy tug of a ray.

We've not found rays a very tasty catch, though John Smith enjoyed at least one, and Europeans consider their rays delicacies. If, however, you'd like to try, say, curried cownose or baked devilfish, ask the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences to send Marine Resources Advisory No. 18 for recipes. But remember, those are meaty wings.

You can't talk big without talking drum. But sitting on the dock of the Bay won't show you these secretive fish. You've got to go looking for them. You do that by knowing where - and when - to look.

When is now. Drum show up in Maryland's mid-Bay each May and June, only to disappear around July 4.

Where, more specifically, is around such Eastern Bay islands as Hooper, James and Tilghman. Fishermen often look around Stone Rock, a mile-wide pile of dredged rocks in about 20 feet of water near Sharps Island Light. Only guess work or experience will get you closer. Even biologists are puzzled. To learn more about their movements, NBT fishing writer Chris Dollar reports that Fisheries Service biologists spent a week this May off the Hooper Islands tagging black drum in an intensive mark-and-recapture study.

If you want to see drum for yourself, hire a charter fishing captain who follows the day-by-day movements of their schools. When you think you're homing in on them, turn on your fish finder and look for blips. Big blips.

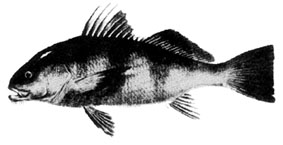

The biggest of Chesapeake's drums are black drum, described as "long, deep and robust." Scales, adds NBT columnist and fishing guru Bill Burton, "are so big and tough that you scale them with a hoe." Puppies of the species weigh a dozen pounds. The big dogs - which may be 50 years old - can reach nearly 150 pounds. The biggest black drum recorded in Chesapeake Bay weighed 111 pounds. It was caught in 1972 in Cape Charles, where they're said to spawn before moving north.

Red drum, black drum's more common cousins, reach a mere 90 pounds.

A fish that big is likely to be hungry, and that's how humans and drum meet. Here's how to catch one, according to Burton: Use a stiff boat rod with at least 30-pound test line. Attach two feet of 50-pound leader, about three ounces of sinker and a very sharp 7/0 hook. Top it off with a generous slab of soft crab, ideally with claw dangling. Once you've found your big blips, drift over the fish, then drop your bait. By the way, close encounters are more likely under a full moon.

If you catch a drum sporting a white anchor tag on the left side of the fish, your report will bring you a reward from the Fisheries Service. Whether or not your drum is tagged, it's rewarding eating. "Its boneless steaks are exceptionally fine table fare. Marinate in lemon and grill like swordfish," says Burton.

Counting the Fishes of the Bay

Everyone who spends much time on the water has a tale to tell of wonders

seen, but taking a true census is a 100-year project. The first systematic

survey was originally published 102 years ago as Fishes of Chesapeake

Bay. S. F. Hildebrand's encyclopedia identified over 200 species with

habitat descriptions, migratory patterns and harvesting data dating back

to the 17th century.

Fishes' 20th-century edition appeared last year, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Describing and illustrating 267 species that live in or visit Chesapeake Bay, Fishes was compiled by environmental biologist Edward O. Murdy with John A. Musick and Ray S. Birdsong from the documented reports of over a century of scientists and watermen.

Batfish, bigeyes, butterflyfish, flying fish, frogfish, goatfish, goosefish, halfbeaks, hogchokers, lookdowns, lumpsuckers, moonfish, mosquitofish, needlefish, pigfish, pipefish, porcupinefish, puffers, pumkinseed, sawfish, searobins, seahorses, sheepshead, squirrelfish, stargazers, toadfish, tonguefish, triggerfish, torpedoes, weakfish, whalesuckers - if they've ever been seen in Chesapeake waters, you'll see them in Fishes of Chesapeake Bay.

We proved that point with charter Captain Jim Brincefield, of Deale. Brincefield tells the story of a fish reeled in at Stone Rock by Pennsylvania fisherman Ronald Lingenfelder. The fish had a suction cup on its head.

"What it was we had no idea," reported Brincefield.

Turns out the mystery fish was a remora. We learn from Fishes that Chesapeake Bay gets occasional visits from four species of remora: marlinsuckers, sharksuckers, whalesuckers and whitefin suckers. The fish caught on Brincefield's Charlotte K was probably a sharksucker, which is "of no commercial or recreational value but occasionally caught on hook and line."

Sharksuckers are not quite true to their name. As well as sharks, they'll attach to barracudas, sea turtles, even ships, buoys and - heaven help us - bathers. What's more, they're "often found free-swimming and occur in shallow inshore waters" and in the Bay as far north as Annapolis.

If you encounter a fish in Chesapeake waters you can't match up with a species in the book, Murdy and Musick "urge" you to take your find to one of the marine centers around the Bay.

The Bad

If sharksuckers visit the Bay, can sharks be far behind?

Sharks come and go in Chesapeake Bay, as any seasoned fisherman will tell you. "The biggest fish caught in Maryland was a shark," recalled Bill Burton, whose four decades as an outdoors writer - 37 and a half with the old Evening Sun - make him a walking compendium of fish lore.

"It weighed about 400 pounds and was caught right at Sandy Point State Park by three fishermen in an 18-foot bassboat. Shark stories were circulating in the Bay at the time, and they went out chumming for one on a terrible day. It's a wonder they managed to land it," said Burton.

Fishes of Chesapeake Bay confirms that those shark sightings - and landings - are not just fish tales. We get common or occasional visits from a dozen species. Among them: basking sharks, which reach "an impossible size" but eat only plankton; sand tiger sharks, which dine on sandbar sharks in the lower Bay; and a nice hardware store selection of hammerhead sharks: smooth, scalloped and bonnet.

Four of our shark visitors share their names with other creatures: angels, bulls, dogs and tigers. Do those sharks share their namesake's disposition?

The angel shark, which bears a strong resemblance to its second cousin, the ray, does indeed have wings and does no harm to any but small fish and invertebrates. Still, it likes to burrow in the soft bottoms rather than fly. Dogfish sharks swim in packs and, like many other sharks, give birth to live "pups"; but they're not known for running down humans.

The stout, broad-jawed bull shark is another story. Happy to eat most anything including mammals, these occasional summer Bay visitors are one of the three most dangerous species of shark. The equally dangerous duo you're unlikely to meet in the Bay. Fishes calls tiger sharks rare in the Bay, citing only one certain visit and that at the mouth of the Chesapeake. Great whites apparently no longer stop by the Bay, though in prehistoric times ancestral great whites as big as box cars lived here.

Like the toothy sharks, a few other Bay visitors are well equipped for offense or defense.

Ray is short for stingray, of which five exotic families visit Chesapeake Bay. As well as the cownose rays that sometimes migrate in great herds, bullnose rays visit. These barnyard species' names seem to describe the shape of the rays' heads, while their family name - eagle rays - describes the strength and endurance of the wing strokes. Bluntnose, southern, roughtail, Atlantic and manta rays - all stingrays - also swim into the Bay.

The stinger of a ray is described by Fishes as "one or several serrated venomous spines." Curiously, the barb is not the tip of their whip-like tail but at its intersection with the body. Encounter it, and excruciating pain may be followed by infection.

Exploring the mouth of the Rappahannock in 1608, Captain John Smith encountered the business end of a ray and thought it would kill him.

Such encounters continue in our own time. In 1986, a mother told me of her 12-year-old son's encounter on the Wye River. After the boy was "hit" in the foot by a stingray, she wrote, "we spent most of August in the hospital with him. There were days we thought we may not have a foot, or a boy."

The most powerful sting comes from a more likely named ray than Chesapeake's barnyard cownose ray. The Atlantic torpedo is as tough as its name. Growing up to six feet and 200 pounds, these rays are, says Fishes, "capable of emitting electric shocks that are sufficient to immobilize a careless human temporarily." You'll be glad to know that no torpedo has been recorded in the Bay since 1922.

A Bay for Every Fish

It's more than a flight of fancy to think of Chesapeake Bay as an aquatic version of the kind of space cantina science fiction fans remember from Star Wars or Star Trek. All three are way stations where diverse species mix and mingle.

Estuaries - and Chesapeake Bay is the United States' largest - are, in the words of Fishes, "boundary zones between different habitats. The Bay owes its species' richness to the incorporation of biotic elements from both the ocean habitat and the freshwater habitat, along with an estuarine biota specifically adapted for life in waters of reduced salinity."

Here fresh wat er from 150 rivers mingles

with saltwater rushing in and out on the tides. From the rivers and creeks

come freshwater species. In with the salt water comes a vastness of microscopic

life spawned in the ocean - plus adult fish that live in the ocean but spawn

or feed in the Bay. The physics of the mixture leads to all sorts of different

zones and columns, which form separate habitats favoring distinct species.

Most abundant of all may be the shallows, where wetlands and grass beds

are nurseries to many species.

er from 150 rivers mingles

with saltwater rushing in and out on the tides. From the rivers and creeks

come freshwater species. In with the salt water comes a vastness of microscopic

life spawned in the ocean - plus adult fish that live in the ocean but spawn

or feed in the Bay. The physics of the mixture leads to all sorts of different

zones and columns, which form separate habitats favoring distinct species.

Most abundant of all may be the shallows, where wetlands and grass beds

are nurseries to many species.

Temperature is another reason the Bay sees such a diversity of fish. In the summer Bay, water temperatures can reach the mid-80s, while winter temperatures drop into the mid-30s. Those temperatures, and the seasonally changing length of day, appeal to the different clocks of the many species. Anybody who reads fishing writers Bill Burton or Chris Dollar knows that sporting fish climb the Chesapeake to spawn with the same by-the-clock regularity as flowers bloom in spring, with early perch and shad yielding to striped bass and drum.

The warming waters of summer are an invitation to the numberless species of the ocean. Writes Fishes: "Fish diversity reaches a maximum in late summer and early autumn, when rarer tropical species may straggle into the Bay to join warm-temperate and subtropical summer residents."

Oddities aplenty visit the Bay - sometimes high up the Bay - in those warm times. Once, a century ago, a blue parrotfish - a gorgeously colored warm-water fish that feeds on coral reefs - was netted high in the Potomac River off St. George Island.

Then, as the Bay cools, fish take their leave, moving south into warmer or deeper waters. Naturally, where the little hungry fish go, the big hungry fish go too.

The bigger they come, the bigger the stir. When a 40-foot whale visited Rock Hall in the early autumn of 1991, Natural Resources Police hunted it by helicopter. Chessie the wandering manatee, who came calling in 1994, made the biggest stir of all. Newspapers and television recorded Chessie's amblings. But cooling waters sent chills down the spines of manatee watchers who, fearing the object of their affections might succumb to hypothermia, set out on a Bay-wide chase. An elusive Chessie was at last caught, tranquilized and flown to the warm Florida waters manatees are supposed to frequent. Apparently the grasses were greener in the Chesapeake. Chessie returned, visiting briefly in 1995 and reportedly again in 1996.

Now it's believed that manatees, too, may be regular visitors to Chesapeake Bay. "Coming to the Bay may be an echo of a very old pattern," reads the newsletter of the Marine Animal Rescue Program. "Europeans who arrived in Chesapeake Bay in the 16th century reported finding manatees."

The Odd, Ugly and Amazing

Whales, manatees and many another oddity venture high up Chesapeake Bay, to the Bay Bridge and beyond, but the greatest congregations - and the greatest diversity - gather just above the mouth of the Bay, between Cape Charles on the Eastern Shore and Cape Henry on the West.

and Cape Henry on the West.

As Chris Dollar wrote in these pages a few weeks ago: "At the mouth of the Bay, the world opens up. Scores of animals use the turnstile where the ocean meets the estuarine waters." Reading those words, I recalled my own close encounters in those waters.

Describing it today, over a decade later, it seems a strange journey. I was traveling as a reporter with the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory out of Solomons. We were catching skates.

The scientist in charge, Dr. Martin Wiley, was studying electromagnetic pulse, and skates, he hoped, would help him explain to the Navy how the kind of energy generated by nuclear warheads affect electronic communications systems. Skates are first cousins to rays and, like them, come naturally equipped with electric sensing organs.

So we motored out of Solomons to the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. Right in sight of the Bay Bridge Tunnel, the scientists dropped their drag net. When, dripping and heavy, the big net was winched out of the water, the whole crew gathered on the deck to see what we'd caught. Before our eyes wiggled the vast diversity of Bay life.

Each haul brought in skates. Strange little kite-shaped creatures, these clearnose skates looked, when turned over, just like ghosts. They'd travel back to Chesapeake Biological Lab to take a turn in Wiley's aquariums.

But skates were only one of the wonders we caught. There were big, flat, flapping rays to be returned overboard; delicate curving seahorses and their straight cousins, pipefish; ugly toadfish and hogchokers mixed with plenty of jellyfish, so we all wore big rubber gloves; flounder and more than a dozen species of finfish.

That day we satisfied our appetite as well as our curiosity on the fishes of Chesapeake Bay.

We Are Not Alone

Which is not to minimize close encounters nearer to hand. It's when you encounter another species from your own dock of the Bay that diversity ceases to be an abstraction.

Some hours, the water is clear enough that you can watch a tiny pipefish chasing its dinner. Some swim, you may open your eyes underwater and find yourself face to face with an American eel. Some nights, the spot are so thick under your dock that, as John Smith did in his day, you go after them with a frying pan. And some June day, you'll be sitting on the dock of the Bay when the rays swim in.

That's when you'll know that we are not alone.

In His Own Words: Captain John Smith on the Sting of a Ray It came to pass that I had pierced a very curiously-shaped fish, and knowing nothing about it, was taking it off the point of my sword as I had done others. It was much of the fashion of a thornback, with a long tail like a riding-whip, in the midst whereof is a most poisonous sting of two or three inches long, bearded like a saw on either side. This the fish stuck into my wrist, to the depth of near an inch and a half; no blood issued forth, nor could any wound be seen, except a little blue spot, but the torment was instantly extreme, by reason of its poison, and in four hours' time my hand, arm, and shoulder had swollen to such a size, and my agony was so great, that I concluded that my death was indeed nigh, and this, my opinion, was shared by the whole company. Foreseeing my death, I directed my grave to be dug on a neighbouring island, a task which was dolefully carried out by my sorrowful companions yet it fell out, as you all know, that I did not die, for it pleased God that by virtue of a precious oil the tormenting pain was, ere night, so well asswaged, that I began to be hungered, and longed for my supper, and then did, with a good heart, have mine enemy cooked, and did eat a portion of him to my great delight, and to the joy and content of the whole company. And the next day, when we left that memorable place, by one consent we called it Sting Ray Island, after the name of the fish. |

| Back to Archives |

VolumeVI Number 25

June 25 - July 1 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |