Our Eyes on Chesapeake Country

with Sandra O. Martin

When you close your eyes and imagine Chesapeake Country, you may be seeing through Marion Warren's eyes.

In half a century of making pictures, the skinny St. Louis orphan who joined the Navy to see the world has become Maryland's - and especially Chesapeake Bay's - signature photographer. He's showed us where we live with such clarity that we've borrowed his eyes as our own. Warren's images come to mind with the easy familiarity of a popular song, branded as sweetly and simply as a tune sung by Frank Sinatra.

At just about Sinatra's age, Warren - who was born June 18, 1920 - has a long view on the days of our lives. He shot his first pictures as a high-schooler not long off the farm in the 1930s. Barely out of high school, he got hired by the Associated Press in St. Louis, shooting everything from "airplane accidents to the straight stuff."

Warren came of age in World War II and enlisted in the Navy, but he missed combat. Instead, he was detailed to Washington, D.C., shooting official and secret assignments for the Secretary of the Navy. One of the lingering images of those years is the last family portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, shot six weeks before the four-term president's death.

After the war, Warren settled in as a photographer of peace and prosperity, capturing the range of life from weddings to soaring industrial achievement. He's been a studio, commercial, industrial and architectural photographer. (His story of how he photographed the Bay Bridge is almost as good as his famous picture.) He's also worked many years as a freelancer photographer, making pictures for world class magazines like Fortune and Life. We in Chesapeake country know him as a devoted environmental photographer, documenting Maryland and life on and around the Bay.

Part of the reason we see through Marion Warren's eyes is that he's shot so many pictures: 100,000. Not counting his client work. Another part of the reason is that he is so canny and courteous in his craft. Working on his own since he left the Navy in 1947, with his young wife and partner Mary and a growing family - Paul, Nancy and Mame - to support, Warren established himself by his ubiquity. Chamber of Commerce, Severn River Association he joined the community groups, came to their meetings, took their pictures; even now, you'll find his pictures in the Severn River Association newsletter.

Valuing exposure and pleasure-giving as much as money, Marion Warren has generously allowed his photos to be reprinted, which is how you've seen his masterpieces in New Bay Times' pages. It's also the reason he - and through him, all of us - came to know Maryland so well. As a young man making his reputation, he bartered with the Maryland office of information, trading photographs for travel. His photographic records of family excursions around the state have come to be all of our family albums of Maryland in the last half of the 20th century.

The Warren family travels have been historical as well as geographic as he and first his wife, Mary, and then his archivist-historian-writer daughter, Mame, searched dusty old records and family albums for images to become books of historic photos. First, with Mary, came Annapolis Adventure: Then and Now and The Train's Done Been and Gone; then, on the Naval Academy, Everybody Works But John Paul Jones.

Next, father and daughter collaborated on Maryland Time Exposures, 1840-1940; and Baltimore: When She Was What She Used to Be. On her own, Mame published Then Again Annapolis.

The Eye of the Beholder documents Warren's 50-year career, and Bringing Back the Bay: The Chesapeake in the Photographs of Marion E. Warren and the Voices of Its People, with Mame Warren, tells the story of Chesapeake Bay's culture, troubles and climb toward recovery.

For all this, Marion Warren was this year named an Admiral of the Chesapeake. Maryland's highest environmental honor recognizes individuals whose life and actions have been dedicated to broadening awareness and conservation of Maryland's natural resources. "His life's work has been capturing the spirit of the people and places of Chesapeake Bay," said Gov. Parris Glendening. "He and his artistry are truly an enduring legacy and invaluable gift to us all."

1998 has been eventful in other ways, as well. Warren is recuperating

from the worst illness of his life, a bout with colon cancer, and a long

list of complications that kept him in hospital and nursing care for almost

six months. His weight dropped from 180 to 139 pounds. Now he's bouncing

back, regaining his strength with another project and  another book.

another book.

When he and his wife of 55 years moved from their home at Ferry Farm on the Severn River to a townhouse in downtown Annapolis, he donated his life's work to the Maryland State Archives, where the catalogued Marion E. Warren Collection is now a resource for us all. This month, also, you can see his photos on display at Barnes & Noble in Annapolis.

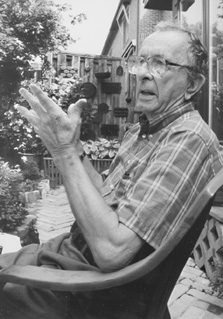

This summer, too, he spent a morning on his pleasant, flower-filled patio talking with New Bay Times. Here now is Marion Warren in his own words.

Q To start out, tell me how to get a good picture of you

A Well, the way I do something like that is to watch the subject to where I feel the expression is natural, then look for it and shoot. The minute you start posing, it becomes a little bit less natural. That's always been my feeling.

photo at right by Betsy Kehne

Q Is the candid image part of a philosophy with you?

A What I like to do is literally be real. I believe in uncontrived and natural photography; I think that's what photography is all about. Obviously not for ads and such, but take this book (he picks up a copy of Bringing Back the Bay). I didn't pose any pictures in that book. Granted, a lot of people knew they were being photographed. But to actually arrange how to stand this way or that, I didn't do it at all. I let them fall naturally, and then I chose my position to take a picture from. I much prefer to do that than actually set people up to be photographed.

Q Perhaps that's why your work has remained interesting to you your whole life?

A I think so. For instance on this book, the publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press, gave me complete freedom to do just as I wanted. Toward the end, before they'd seen anything, they got a little bit scared. But after they saw the book, they were very pleased with it, they left me alone to do it.

I've been a professional photographer for 60 years, and this is the first

time I had gotten to do things entirely my way. Because any time you work

for someone, you have to have a certain angle. If you were doing it yourself,

you'd probably do things a little differently. Pro fessionally,

you always have to take the client's needs into consideration.

fessionally,

you always have to take the client's needs into consideration.

Q Tell us a bit about making photography a profession.

A When I taught photography, I would always say 'look through a dollar bill sign when I take a picture.' The students would gasp. I'd explain that I have to do the picture the way the client is going to use it, not the way I want to do it. I chose the way to do it, but I always had to keep in consideration how they would use the photograph. If I didn't, I would have missed the boat completely.

Q So you had to be smart about what your client wanted?

A Exactly. I always felt you had to do the thinking. Here's an example.

Once a client wanted a picture for an ad that would show that their stainless steel was different - and better - from anybody else's. Now, you look at stainless steel, and as far as the metal is concerned, you can't tell the difference, whether it's from Eastern Stainless or Bethlehem Steel. As in making a cake, it's the ingredients that count.

I went down and spent two days on that particular shot arranging the different metals that went into the ingredients. I made little piles and big piles and took a picture of it. It made a very popular ad.

Q Sounds like you became as good a psychologist as photographer.

A I say that 90 percent of being a good photographer is diplomacy in working with clients, and 10 percent is using a camera.

One of the most interesting assignments I ever had was when working for National Bohemian Beer, when they did the Land of Pleasant Living.

I have this reputation for natural photography and that's the way they wanted to show the Chesapeake Bay. They wanted to show it as the people who worked there in very realistic pictures. They'd give me a general subject, like clamming, and I'd go out and do pictures of people clamming, knowing that it had to fit a certain size and space and that it had to be vertical or horizontal. That was the only restriction I had, and I'd come back with dramatic photographs that would depict that.

One day one of the biggies from a big advertising agency in Baltimore came down in his Mercedes, all dressed up in a necktie, coat and everything, to go with me.

So we went down on the shore, maybe to Deal Island, and we'd see some waterman sitting there, and he'd get out of the car and go over and talk to the watermen, and they'd say "nope, we don't have any clams, we don't have any crabs, nope, nope."

I said, let me come back on my own and I'll get your pictures. He said if I can't do it, how can you? So I said, just let me.

I went down and had no trouble at all. I got out of the car, didn't take a camera or anything, and sat down and talked to the men and asked how were they doing, and this and that, the weather, anything else. Pretty soon, I'd say I'm down here taking pictures for National Bo, you know the ad they're running on the Land of the Pleasant Living. I'm looking for people to be in those ads, and you guys look like ideal subjects. Well, by this time we were friends. And they said sure.

In other words, it's like photographing wildlife. You've got to fit in. You go into a field where there's geese, and if you charge into that field, they're gone. But if you park, go up to the fence and sit there and they don't move, and you go very slowly, maybe then you go through the gate, and it may take 15 minutes getting toward them to where you want to be, and they won't fly. You can push it too hard, and they will. But then, you make your pictures, you ease yourself out and go again.

It's the same way with people. People are just as shy of cameras as wildlife is. And they should be. After all, it's taking a mirror image of you. So it's very important to be unobtrusive, to become part of the background, part of the scenery. And it works every time if you do it carefully and slowly.

Curtis Bay Towing Company used to have me cover the maiden voyage of every ship into Baltimore so that they could present the captain with a 16 X 20 print of their tugs assisting his ship. I'd get up at 3am and be out to the ship as she approached the harbor at sunrise. The most interesting time to cover the port is at dawn; the light is moody and there's always lots of action. This is probably the best photograph I ever made of a tugboat, but Curtis Bay never used it because it didn't show their vessels at work.

-Bringing Back the Bay

Q Do you work in black and white or color?

A I prefer black and white. I love black and white and I love getting in the dark room and making the print. But more important, black and white negatives are archival; they'll last as long as you take care of them, where color will not. I was documenting this for future generations.

I also feel very strongly that people read the content of a photograph more in black and white than they do in color. In color, they're distracted by the color. So suddenly after doing 30 years of photography the way the client wanted, and that was mostly color, I went back and did Bringing Back the Bay in black and white, and now my reputation is that I'm the great black and white photographer, and that suits me just fine.

Q You always use the word, "make a picture," rather than "take a picture" and I know that must have a meaning to you. Will you explain it?

A Well, it means that you arrange it, you make your own composition. If you take a picture, you take what's out there. To make a picture, I always feel that you're choosing the exact angle, the exact height or what's in the picture or what's not in the picture. That's why I use that term.

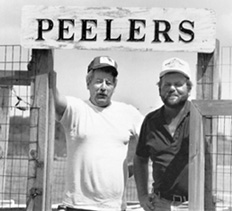

When Warren returned to Deal Island 30 years later, he still had the knack, as this 1988 photo of Don Cawood and Keith Thomas on Deal Island shows.

Q It sounds to me that you've managed to get for yourself a life where discovery and creativity are just like toast in the morning.

A You're exactly right. I've had a marvelous time.

And one of the nice things about it has been that when I got tired of doing one thing, I went and did something else and was always able to make a living at it. A good example of that is the studio here in Annapolis. When I got to where I didn't want to do that, I began to branch out in to other fields and build up my technique and then abandon the portrait field. That's how I got started doing architectural photography, and when some of these architects appeared in Fortune magazine, Fortune began to hire me to go on assignments for them. And that was fun.

Q So you've had some extraordinary angles and views on life?

A Yes, for instance, on a shoot for Fortune of an executive's house in Sister Bay, Wisconsin, I climbed all the way down to the water's edge, and looked up at the house hanging over the cliff, things like that, in the fog.

Growing up on a farm, I rode horses all the time. Baltimore Magazine wanted a story where horses run with the hounds - Point to Point, I think the title is. They all ride through the woods and around, and the only way I could do it was to ride with them.

Now Racing Aboard Freedom is a picture done with a 4 X 5 camera. I climbed out on the bowsprit of this boat and shot looking back. I couldn't do that today.

I've done lots of aerial photography, including out under the wing of an airplane. I've shot out of a helicopter. I like a helicopter very much. You can put yourself right where you want to be exactly.

I've been up on top of both towers on both Bay bridges.

Q So you can't fear heights or bridges in your job. Did you get good pictures from up there?

A Oh, yes. When you're up on top, you can see Baltimore on a clear day.

Q How did you shoot those wonderful

Bay Bridge pictures?

A I took six or seven trips out there before I got the pictures I wanted. I wanted some clouds, and it was either too cloudy or not cloudy enough. So I kept going back, and I discovered the only time the moon came up over the bridge was in June and July. That was from the roof of the old ferry terminal, where you had to climb up about six stories and walk across the beams and crawl out on the roof. And this again is with a 4 X 5 camera, tripod and holders and things.

Mary had gotten used to my going out there, but I'd come home. This particular night when I was getting my clouds and everything, I stayed until I got my picture, and it was pretty near 10pm. She was sure I'd fallen off the bridge by that time. Well, of course, I hadn't. I got the picture.

Q Do you have to be like a fisherman, who's up first thing in the morning and last thing at night?

A Yes. The best pictures are made before 10 in the morning and after four in the afternoon. Because you don't get any overhead light.

My oldest daughter, Nancy is married to a farmer down in Pocomoke City. They have a farm house on a country road. I looked out one day, and looking east, here's this field of soybeans. Tomorrow morning, I said, the sun will shine across this and be rather dramatic.

Upstairs, the front bathroom gave me good height to look down on this field. Next morning at 6am, before the sun was up, I got up and went out to the car and got my camera and tripod and film holders. I went upstairs and took the screen out of the window, closed the bathroom door and opened the casement window and set up the tripod camera.

All this took time, and then I had to wait for the sun to come and give me the misty light. So I made the picture and folded up the equipment and opened the door, and there stood my son-in-law outside the door in his underwear saying, 'What the hell have you been doing in there?' He never has really understood me as a photographer. I think I embarrass him a little bit because I don't do day labor.

Q What are you working on now?

AI'm now working on a project that I started about 15 years ago. I wanted to do documentary portraits of the people who leave their fingerprints on Annapolis.

I've done 60 or 70 people now, from the little boy who delivers our paper, to our mailman, to the mayors, to councilmen, to lawyers and doctors and people like that. I call it "Friends and Neighbors."

I set up the appointments, and fortunately, they are flattered when I ask them. I'm doing it all on a 4 X 5 camera with tripod and strobe lights. They're all posed photographs, but I'm posing them in natural settings, where they work and things like that. I'm having a lot of fun doing it.

I try to do two or three a week, if I can. Since I've been out of the

hospital, I've done eight different people. Each one of them darn near kills

me, because I have to do them on location and have to carry the equipment,

put it in the van, take it to the site, carry it in and set it all up, take the pictures,

take it all down. But it's good exercise, and that's what the doctor says

I need.

it in and set it all up, take the pictures,

take it all down. But it's good exercise, and that's what the doctor says

I need.

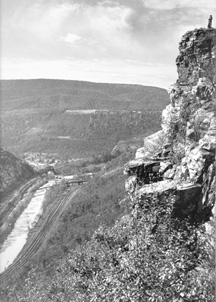

A favorite photo from the Warren's Maryland travels

Cumberland Narrows, 1958

This is my favorite portrait of my wife. We were on a trip celebrating our 15th wedding anniversary. The cliff up there is called "Lover's Leap." My wife and I stayed there one night and the next day, we went and climbed it - and I hauled a 4 X 5 camera up there. She's up there, and I'm on another outcrop. I tried to get her to walk out on the edge, but she wouldn't do it.

Q Here and in all your work, you seem to find that ordinary life has enough of a story

A The one thing that bothers me about photography today is that everybody's got to do something different and everybody's got to be a little unusual, and they overlook the everyday life of people. I don't think I really got into photography until I realized that capturing life is the most vital thing photography can do.

Really, it is. Documenting the real life of people, their real existence. No other art can do it. The artist can't do it; he can only do his impression of it. It's like our books of early photography. Those pictures are real, exactly as things were in those days and not what the caption says, they wore such and such, and all that. Somebody commented on the Annapolis book, how wonderful it must have been to live in Annapolis in those days, the streets were so clean, and I said, see that little stream running down the gutter? That's sewage. You still want to live in those days? Nobody talks about that, but there it is. The pictures show it.

Q Do you think that the homogenization of modern times is going to take away the distinctiveness of things?

A No. When I was getting started in photography, a salesman from the Kodak Company said, you're late getting into photography: everything's been photographed. I always laugh at that. Nothing's been photographed yet

Q This suggests to me that you've lived your whole life in this state of heightened awareness of what it means to be alive.

A Yes, you're exactly right.

Q Did any stronger sense of that come to you after your recent stay in hospital, or were you already there?

A I tell you, I haven't quite settled down. It was an experience that changed my viewpoint on life to say the least, because I'm lucky to be here, number one. But I do want to keep on creating, I don't want to sit back and retire. And I figure I can still leave a few more trails behind.

NBT contributing editor M.L. Faunce assisted in this story.

Due to download times, all photos included in this week's print edition are not online. Please pick up your FREE copy of New Bay Times at any of our 300+ distribution spots.

| Back to Archives |

Volume VI Number 27

July 9-16, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |