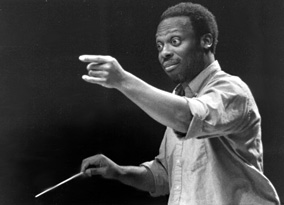

NBT Interview: Maestro

Leslie Dunner

Annapolis' New Music Man

with Sandra O. Martin and Kim Cammarata

He's one in 279, this Leslie Dunner who appears in our town September 5 and 6 to lead the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra into the new millennium. Nearly three hundred conductors competed for the job he now holds, and he beat out them all -- at least two in man-to-man, music-to-music competition -- to take the baton from the world-famous Gisèle Ben-Dor. Hopes are that Dunner will "take the orchestra to a higher artistic level," said Annapolis Symphony Orchestra Executive Director Jane Schorsch. "We expect that he will attract new talent to our orchestra and new audiences to the concert hall."

Just who is this Maestro Dunner?

In many ways the least likely of the four finalists to head a conservative institution in a conservative town, Maestro Dunner is a surprise.

He's youthful - just how youthful he won't say, though he admits to being the youngest performer at the New York World's Fair in 1964. He's African American - and though a third of Annapolis' population is and historically has been African American, our capital's institutional leaders have never been numerous. He's hip -- so attuned to America's cultural currents that a better word might be hip-hop. He's antically eloquent -- expressive with face, eyes, body, voice and words as well as with the conductor's traditional instrument, his hands. He's multi-talented -- as well as conducting, he plays the clarinet, dances and has acting as his next project. He's populist -- committed, he told New Bay Times in this face-to-face interview, to a symphony that's exciting to short-- as well as long-hairs, low-brows as well as egg-heads.

And -- though this should come as no surprise -- he lives and breathes classical music: it is the world and atmosphere he has made his own. Listen, as we did, to Leslie Dunner speak of this music, this world, and he transforms before your eyes into a remarkable artist who loves conducting with every inch and ounce of his being. His voice, beautiful and melodic, calls to mind the music he loves. His eyes, deep and dark, overflow with plans for his new orchestra. His lithe, athletic body, unconsciously rhythmic, exhibits his passionate desire to make classical musical alive and relevant for every ear. Dunner makes you yearn to hear the powerful music that moves his mind and soul.

Catch him while you can. It's a fast life he leads, conducting most weeks of the year, most any place that calls him or one of his three orchestras. As well as the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra, he leads the Symphony Nova Scotia in Halifax, Canada, and the Detroit Symphony, where he is completing a final year. As a guest conductor, he will travel next month to South Africa and Japan, sandwiching those visits between regular work in Halifax and Detroit.

Meet Maestro Dunner -

Q With what hopes do you come to Annapolis?

A I don't come with hopes; I come with expectations. I think for me hopes is the wrong word.

Q Then let's say it this way. What do you like about the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra?

A What I like is willingness to be flexible. I always think an orchestra sounds best when they can be flexible and pliable. This orchestra showed a great willingness to do that.

Q Help me understand what you mean

A In a body of musicians, flexibility means willingness to play with an interpretation that is not strictly at a particular tempo. To be able to play small nuances within a phrase in the way an individual pianist or singer would.

If you wanted to sing something in the shower you could do whatever you wanted. If two of you wanted all the rest of us to sing with you at the same time, you couldn't sing it the same way you would in the shower because we wouldn't sing together. What I mean by flexible and pliable is that somehow all of us would get together and give it the same sort of feeling that one person in the shower can.

I don't want us to sound like a military band who needs to march in step. I want it to sound like we're flowing, we're moving, we're walking. There's direction, a sense of continuity. But it's not so regimented that it loses its personal nature. I think that flexibility is what makes music sound personal. That's why when we listen to a soloist, it's so exciting. It's possible to achieve that with an orchestra. It's more difficult, but it's possible.

Q That's interesting. I think your approach is what my husband must be looking for, because he complains that when he goes to the symphony, no one in the audience moves.

A I don't think symphonic music is like that at all. The concert experience is in part what the conductor tries to create in terms of ambiance. But in part it's what the audience wants it to be, as well. We feed off of each other. So if you have a conductor who encourages a sense of flow and movement on stage, there is more of a feeling of ease for those sitting in the audience.

Again, if you're watching someone and they're moving in a machine-like fashion, you won't get the same comfort as you would watching a tennis player who is all over the place and has to be able to react very quickly. You would feel more comfortable watching the tennis player.

What I want to create in the hall is that feeling of comfort for the musicians. If they're feeling comfortable, not relaxed, but comfortable enough to respond, to react very quickly, then the audience picks that up. I think there's a general sense they can enjoy themselves. That's true whether the music is serious or the music is fun. You can have fun music and still have everyone sitting at attention. Or you can have serious music and have everyone sitting back and letting it all be absorbed.

There's a wonderful television commercial with a guy sitting in front of a stereo. The music starts to come out, and you see the wind blowing him. The chair gets blown away. That's what should happen to the audience. It should be like they are being blown away. If they're really rigid, then they can't be blown away, no matter what's happening on stage.

Q Do you think that's part of why, of

the four conductors who visited last year, you were hired?

A I think that's what the musicians reacted to, though I didn't state it so explicitly with them. It's something that a lot of orchestra members don't get from the person at the podium because usually the person on the podium is concentrating so much on getting this musical ideal across. For me, the musical ideal doesn't work without this other parameter. You've got to have this feeling of it being awesome.

I watched a concert in Detroit with a bassoon concerto. It was a piece I'd never heard of by a contemporary of Mozart. In the audience was an old guy, maybe 65 or 70 years old. Big, big stomach, red suspenders, plaid shirt. I'm watching this guy and he's bouncing all over the place. I'm wondering, what is it that he's hearing? There was nothing earth-shattering about the melody. It's no big, hard-rock beat, but he's having the time of his life. Because the players up there were doing something that made this guy feel really good. I don't know what it was, but for him it felt really good. Looking at him, you would never imagine him to like classical music. The first thing you would think would be his wife must have dragged him here. But she was sitting there looking very proper, while he was having the time of his life. That's what I want.

I want people to come not because this is where they should be but because it's the place to be. I want them to be there because they know they're going to feel something. Whether it's exciting, or whether it's going to make them feel sad, or angry or nostalgic or surprised. I just want the audience to go away and feel like they had an experience.

Q So symphonic music is not just an intellectual experience?

A Yes. For some people, it's intellectual and if it doesn't have the intellectual component, they're not happy. I hope to please those people, as well. But that's not my goal.

Q You're also talking about visceral and kinesthetic experiences

A Right. Exactly. Some people need to respond to whatever the art form is with their full being. Some people need to respond with their soul. Some people need to respond with their intellect. Some people need to respond with all of the different components. I want to be able to tap into all those different aspects.

Q You dance, too, don't you?

A Movement is important. Whole body movement is an integral part of conducting for me. I just can't express myself with my hand and my arm, because I don't hear music just with my ears.

I grew up learning African music and African dance. In African culture, you utilize different amounts of each component. If you are a dancer, you have to be involved in the music. If you play the music, you have to, on some level, be involved in dance. It's impossible to separate the two aspects.

Q How do you and the orchestra communicate?

A It's an interesting dynamic, a very interesting dynamic. The first method of communication should be the hands: what the baton says. In terms of speed and volume, the way we want them to play, loud or fast or slow, has to be communicated with the way we move our hands.

So I could move like this [he sits stiffly in his chair, extending one finger like a baton, jerking it up, then down, left, then right: a perfect, rigid right angle] and it says one thing.

I could move like this [he relaxes his body slightly, moving his whole hand back and forth in the lazy manner of a porch swing] and it says something else.

Like this [body draped on the chair, he moves his hand in long, slow figure eights] and it says yet something else.

Or I could move like this, [he sits up a little straighter and, leaning forward slightly, pinches two fingers together to make little tapping motions like a bird pecking at a crumb] it doesn't say much, in and of itself. But if I combined it with that, that's sending yet another message.

The second element we bring in is the extended body movement: the upper arm and torso. We try not to use anything below the torso because then the musicians at large can't see it.

Q No Elvis Presley kind of stuff?

A Right. Although we do it sometimes because we feel it, and it's great for the audience, it doesn't do a thing for the orchestra. They can't see it.

The next element would be to use the face, expressions, eye gestures mainly. The same way individuals communicate on a one-to-one level, orchestras and conductors communicate on a one-to-one level.

QDo

you talk out loud to the orchestra?

QDo

you talk out loud to the orchestra?

A Oh yeah. Louder. Softer. Watch me. Oh yeah, we do a lot of talking.

Q The gestures you were making and the expression on your face, I was thinking that is exactly like sign language. They way you communicate without speaking.

A There are a lot of similarities. I actually would like to learn more about signing. Not so much as a communicator form, but as an art form in a real pure sense. And physically, I would like to learn more about the science of signing so that I understand better how to use the body to be specific.

Acting is my next big project, learning better how to use my full body because actors have to play not only through their words but through their gestures.

Q You said that you grew up involved in African music and dance. Tell us about your background.

A I'm a New Yorker. I grew up in Harlem and the South Bronx. You can't get any more urban than that. My parents are now retired. My father worked a lot of different jobs. He worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard before the fire there. He worked for the Brooklyn Department of Sanitation. He worked with the Department of Transportation making street signs. My mom worked mainly as a social worker and community activist.

Q Not musicians?

A Pretty far from music. About as far as you can get. I come from a working-class family.

Q How did you get involved in African music and dance?

A Mainly through my sister. She was interested in the roots of our culture, Nigerian, African culture, and anything she was interested in, I had to follow along. I actually became quite good at African dance. I danced at the New York World's fair in 1964. I was their youngest performer at that time.

Q And your life has remained musical

A The form now is very different. I went to high school in music and art. Unfortunately, our society, at that point didn't encourage young people to stay active in diverse activities. I wanted to learn about jazz, and they wouldn't let me. They actually refused to let me participate in jazz events. When I went to college, at the University of Rochester, I didn't think it was possible to continue doing that and to be active in classical music. I thought I had to make a choice.

QA definition would help us out. Just what is this form called classical music?

A Classical or symphonic music comes from essentially a European tradition of art music of the 18th and 19th centuries. By art music, I mean music that was not popular music. The Top 40, the Beatles, Jefferson Airplane, Michael Jackson: that's popular music. Leonard Bernstein, George Gershwin, even someone like Scott Joplin in some ways: that's classical music.

Scott Joplin, for example, could write piano rags sitting down in a smoky bar, or he could write an opera that uses those same elements as the music from the smoky bar but writes it in a different form, puts it in a different architectural form. That's what makes it classical. Mozart took a lot of popular songs and put them into operas. Consequently, a lot of operatic music ended up becoming popular songs. So you can take one and influence the other.

Q So it's the architecture of a work that makes it classical?

A Right. Andrew Lloyd Weber's Phantom of the Opera: a lot of that could be considered art music because of the format. But the way he utilizes the individual core songs is very popular.

QYou're telling us that the kind of music you play is not a still body of water. It's a constantly refreshed stream?

A Right. That's what ultimately makes what I like to do exciting.

Q Tell us about the musical season you've planned. The symphony's executive director, Jane Schorsch, described your chosen program as conservative.

A Yes, this is a very conservative season upcoming. In part that's because I want us to have a staple in our repertoire of what has preceded us in the tradition. It's also a little easier to fund. The more exotic you get in your choice of music and repertoire, the more expensive it becomes. I want to bring that into our repertoire for our seasons more gradually.

In the second season, when the repertoire becomes more adventurous, the orchestra will be able to play it even better, and the audience will be ready to hear it.

Q Give us an example of the range of music

that people might hear that's conservative this coming year.

A Brahms' First Piano Concerto No. 1, which opens our season, is about as conservative as you can get.

[At the other extreme] in February, we have a piece that I wrote, that's having its American premiere that I am sure no one is going to know. It's called Motherless Child Song, and it's based on spirituals. Kishna Davis, the soprano who came in for my [audition] concert last season, is coming back.

We're ending the February concert with a symphony by Howard Hanson, "Romantic," that people will probably know and recognize. So three-quarters of the concert people will probably not know. One-quarter they will. That's going to be very different from most concerts that I do. So within the spectrum of a year, I'm giving audiences a sense of what they should start to expect in miniature of future pieces.

While this season is for the most part traditional, in subsequent seasons there will be much more of an influx of unfamiliar territory for our audience members. So I want them to get used to this concept.

Q What promise does your coming here make to the audience?

A I think the only promise I can make at this point is things won't be boring. I don't know if they'll be liked or not liked, but they certainly won't be boring. People have to make up their own minds as to whether they like something or not. If they go out with just an opinion, then I'm really happy. Then it means something happened, and they're thinking about what happened to them, and it's something they want to share with someone else. Whether it's pleasurable, or infuriating, or anxiety-producing, whatever it is, it's good. As long as they're here.

Q Are you going to make this Annapolis Symphony Orchestra the kind of place and occasion where people might feel free to come in say 'I may not have tried this recently or ever, but I'd like to see what this new guy's going to bring'"

A By all means. That's why we're starting with parks concerts, to encourage people to do exactly that. And to do it with their families so that it's not a formalized kind of mindset. For me that's important. That's an important mission with these concerts.

By the same token, I don't think it's necessary for people to feel like they have to get all dressed up to go to a concert. When I was a student I used to love to go to the Metropolitan Opera for performances, and I would dash in at the last minute because I was always trying to get a ticket from somebody who didn't want theirs. I would go in shorts and a T-shirt, though I'd try not to be sweaty because that's rude. It would drive the other patrons furious; they're sitting there in furs and jewels. Hey, I'm not furs and jewels. I want to feel comfortable for me.

Q So you might be in the news. Like Stravinsky when they stormed the hall.

A Right. Hopefully we won't have any scandals where they tear down the hall. But if we have scandals where everyone jumps up and they're just thrilled, that's good news for us.

Listen to the Music

Celebrate with Annapolis Symphony Orchestra the opening of a new era at free "Popular in the Park" concerts Sat. Sept. 5 at Down's Park in Pasadena and Sun. Sept. 6 at Quiet Waters Park in Annapolis. At both concerts, Leslie Dunner will be introduced by County Executive John Gary.

On the program: "American Salute" by Morton Gould; a suite from Carmen by Bizet; Strauss waltzes and polkas; the famous "William Tell Overture" - the Lone Ranger theme music - by Rossini; Richard Hayman's "Pops Hoedown"; music from "The Lord of the Dance" by Ronan Hardiman; "Maple Leaf Rag" by Scott Joplin; Leroy Anderson's Bugler's Holiday; songs from Porgy and Bess by George Gershwin; Ralph Hermann's "Old Timers Waltz" medley; and the Armed Forces Salute.

"It's a lovely mix of American and traditional," says symphony executive director Jane Schorsch. "There'll be things people recognize and maybe one or two things they don't know as well. It's about 75 minutes of wonderful music. Come and bring a picnic supper."

After that pair of free concerts, the music continues in several series; call early for reservation: 410/263-0907.

Symphonic Series Fridays and Saturdays Sept. 11 & 12, Nov. 20 & 21, January 22 & 23, Feb. 26 & 27 and May 14 & 15 at 8pm · $95-140 for five concerts

Camerata or Chamber Music Series: Fridays Oct. and April 16 at 8pm $34-46 for two concerts

Holiday Pops Concert Friday Dec. 18 at 7pm $25-30 for one concert

Family Concert Series Saturdays Oct. 31 and March 27 at 2 & 3:30pm Students $12; adults $20 for two concerts.

| Back to Archives |

VolumeVI Number 34

August 27-September 2, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |