FAST LANE

Drivin' Donnie Neuenberger

In Daytona, a fast Pontiac - and ESPN 'face time' - spelled success for Donnie Neuenberger

When Donnie Neuenberger looks out his Edgewater

window, he views Beard's Creek differently than you and I do. When he casts

his eyes, on water or land, he looks at the horizon first and then works

his way back.

He's in training, you see, for looking forward on a racetrack at what sort of action or confusion may be unfolding far ahead of him. At 165 mph on the straight-aways, drivers make choices in nanoseconds that determine if they will race another day.

It was in the spring of 1992 - on the weekend that racing icon Clifford Allison died at a track in Michigan - that Neuenberger needed split-second timing. He was racing solid at Nashville Motor Raceway, running fifth, when the car ahead of him blew a tire. It spun into the wall, rebounding directly into the path of Neuenberger's Pontiac.

In the parlance of racing, Neuenberger T-boned the spinning car - crashed full-speed into its side.

"When you get in trouble, it's like being in the middle of a tornado; it's all a blur," Neuenberger says.

He walked away from the crash. The next day, his neck ached mercilessly from whiplash.

But when you're moving as swiftly as Neuenberger - on racetracks and in life - nothing hurts for long.

Inside NASCAR

When he headed to Florida last month, Neuenberger raced to a new stage

in life.

In the week leading up to NASCAR's Daytona 500, Neuenberger raced in the well-known Goody's Dash Auto Parts 200 at the famed Daytona International Speedway. It was the inaugural event of 18 races in the Goody's circuit that Neuenberger plans to compete in this year. The real grind begins on May 2 at Hickory Motor Speedway in North Carolina.

NASCAR racing has traveled a long way since it was founded by Big Bill France in 1948. In his newly published book, The NASCAR Way, Robert G. Hagstrom explains that the sport has grown from local competition between moonshiners into a $2 billion industry.

It continues to grow, with the likes of DuPont, Kellogg's and Anheuser-Busch signing on as sponsors. It's the biggest spectator sport in America and people are still lining up: When the Winston Cup added a new racing date on March 1 to the Las Vegas Speedway, all 100,000 tickets sold six months beforehand in 30 hours.

In NASCAR, the Goody's Series that Neuenberger is part of ranks just beneath the Winston Cup and the Bush Grand Nationals in competitiveness and money.

Speaking of money, the uninitiated may think a driver owns his own vehicle; maybe keeps it in the garage and crawls around beneath it with a wrench before tooling it to the track on Saturdays.

That may be the case with local short-track drivers, but it is far from the way it works on Neuenberger's level. His car is owned by Moore's Racing out of Hendersonville, N.C., a team that keeps a stable of two to four cars and maintains a yearly budget of several hundred thousand dollars.

It sounds like a lot - until you compare it with some of the combines on the Winston Cup series, running 15 to 20 cars and spending $10 million along the way.

Of course, money is coming in from sponsors who gain plenty when their name is emblazoned on race-cars, pit-stop areas and every cap, jacket and shirt donned by a driver. Olympic athletes with their Nike swooshes have nothing over NASCAR drivers when it comes to transforming themselves into walking billboards.

"You take care of sponsors, and some of them have egos as big as houses," Neuenberger observes, while sitting in his all-white kitchen amid jackets, T-shirts and decals.

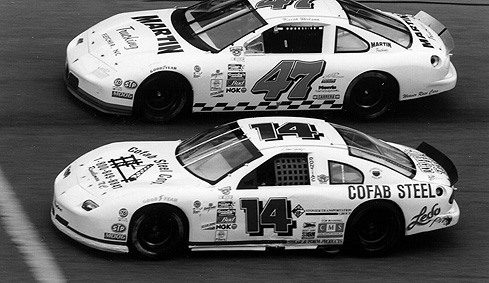

Of course, those high-maintenance sponsors wouldn't

be among Neuenberger's bankrollers. They include Cofab Steel, a major North

Carolina company; Maryland's Ledo Pizza; and Wyvill's, the popular sports

bar in Upper Marlboro.

Of course, those high-maintenance sponsors wouldn't

be among Neuenberger's bankrollers. They include Cofab Steel, a major North

Carolina company; Maryland's Ledo Pizza; and Wyvill's, the popular sports

bar in Upper Marlboro.

Racing indeed has come a long way since the days the moonshine boys plied country arteries a step ahead of the law. These days, NASCAR drivers are bright, articulate fellows who take care of their bodies and their business.

Neuenberger fits the new mold. He has his own radio program, and he's aware that dealing with the news media is essential to success.

Like NASCAR, Neuenberger, who grew up in Brandywine, has come a long way himself since that day in his 20s when some friends persuaded him to go to a race with them at Dover Downs in Delaware.

"After a few races, I told them that's what I want to do. I wanted to be down there in the pits. They kind of laughed at me, but a few years later, they weren't laughing," he said.

Not only weren't they laughing, you can bet they were watching when Neuenberger headed to Daytona in February.

Race Week Day One: 'Face Time'

"I felt pretty confident going to Daytona. I was pretty sure I was going to have a decent car. I didn't know if I would have a fast car."

His car was fast indeed.

The 350-cubic-inch, four-cylinder Pontiac Sunflower, with No. 14 emblazoned on the sides, more than held its own against a field of six-cylinder engines, averaging 159.216mph on the 2.5-mile track, the second fastest qualifying time among 61 cars. Not only was it fast, it was fast at the right time - at the start of race week when the ESPN crew was getting to know drivers.

If you're a racing up-and-comer like Neuenberger, you know not to be moody or grumpy around a reporter even if your engine blows on your first lap. Saying "no comment" to a television camera or a reporter is bidding adios to future sponsors.

So when ESPN's "Dr." Jerry Punch arrived with the microphone, Neuenberger was smooth, smiling and, as usual, well-spoken. Forget the 150-mph curves he had just survived; that moment on ESPN was the most important of the week. In Neuenberger, the ESPN crew had found a player: someone accessible and articulate, someone to follow.

Afterward, the talk wasn't about performance or speed. "Everybody kept asking me, 'how'd you get on TV like that'?" Neuenberger said.

Day Two: Rookie Mistakes

In the blush of success, Neuenberger had a slight bout with forgetfulness. And he wasn't alone. He was one of about eight drivers who neglected to stop by a racing office and "draw a pill" - pull a number bingo-like to determine race position for another day of qualifying.

So he was penalized, made to run early - the sixth car out - in the afternoon

Florida sun at 3:30 o'clock. Every driver knows this is not desirable because

stressed motors like those blazing round and round at Daytona perform better

in cooler temperatures.

Drivers and their crew always are looking for an edge, tinkering in hopes of shaving a mile-per-hour or even a few 10ths from their time. But sometimes crews can outsmart themselves by over-inflating the tires. Harder tires can mean more speed but the balance is a delicate one, as Neuenberger found when the fattened tires caused his car to "bobble," in racing lingo, leading to a loss of a mile-per-hour or two and keeping the Sunflower under 160mph.

But there were other important matters to tend to: television. The qualifying session was broadcast live on ESPN. And because Neuenberger ran early and fairly fast the day before, they referred to him frequently during the broadcast.

And once more, they interviewed him for a national audience.

Day Three: 'Bump' in the Stretch

A good race position assured, Neuenberger spent the day before the big race fine-tuning his Pontiac Sunflower with new shocks and stiffer springs. Practicing on the track, running 110 octane fuel, he wanted to run hard - but not too hard.

"You don't want to put too much wear on small motors; they're time bombs," he said.

He was running in a four-car train when the driver on the outside pinched him to the middle and he bumped the car on his left. The car running on his inside spun and went airborne - narrowly escaping calamity.

"He never had been for a ride like that," Neuenberger joked.

Collisions of any sort at 160mph-plus can spell disaster, but Neuenberger came away with nothing more than black tire marks on the left side of his car. "I never even got off the gas pedal," he said.

Race Day: Friday the 13th

In the old days, NASCAR drivers had a reputation for living as hard as they drove. Neuenberger is among those who keeps in good shape, he says, to better withstand the nerve-jangling rigors of flying on the ground for nearly three hours while fighting powerful G-forces around curves.

Neuenberger was a star athlete in high school, playing on state champion basketball and baseball teams. "They talk about racecar drivers not being athletes. Try sitting in a hot box for three or four hours," he said.

He wants a good night's sleep especially before race day and, as he puts,

it gets very focused. The morning of the big race last month, Neuenberger

stuck to his habit of drinking coffee and several bottles of water  to stave off dehydration once the race begins.

to stave off dehydration once the race begins.

(People, especially women, often ask him 'what about going to the bathroom during the long race?' His answer is that there is no time and that the competition is so intense that he doesn't even think about it.)

At race time, which was 11am in the Goody's Dash Auto Parts 200, there was nervousness, to be sure. In the back of drivers' minds in this dangerous sport is the realization that they may have drunk their last cup of coffee.

For Neuenberger, the nerves calm swiftly: "Once I step into the car and we get through the first couple of laps of the race, then it's fine."

At Daytona, something unfortunate happened early in the nationally televised race that set the tone for Neuenberger's day. Three or four laps into the race, he felt something wrong with his car: It turned out that he had sliced a rear tire, apparently from metal debris on the track from an early incident.

Neuenberger pulled his No. 14 Pontiac into the pits to change the tire, a process that takes just 10 seconds or so. But it was a costly stop, putting him a lap behind the leaders.

He recovered throughout the day, passing 28 cars and running with the leaders for much of the race - but still a lap behind. But he couldn't get a break, as he puts it, to pass the leaders.

The result: He finished a respectable 12th of the 42 autos that made it through the race, enough for a modest check of $5,000 that he signed over to his racing team. Yet for Neuenberger, it was a successful Speed Week in his first voyage into racing's big time.

Even running a lap behind, he got great television exposure running with the leaders. Neuenberger summed up his week thusly: "We didn't win the race. But we sure won the media war."

The Next Lap

In his waterfront home in Edgewater, shared with his twin brother, Ron, the unmarried Neuenberger sat at his kitchen table a few days after the race with fan mail scattered in front of him. He drank his coffee from a mug stenciled with a busty woman.

A young woman from North Carolina had seen him interviewed on ESPN and didn't conceal her interest. "If you ever come to Charlotte, look me up," she wrote. (Hmmm, his next race is in North Carolina.)

With NASCAR booming, drivers like Jeff Gordon and Rusty Wallace take on the aura of rock stars. It's a high life, but also a stressful life, requiring hustling for sponsors and media exposure when not defying the laws of physics. But it's a life that Neuenberger seems fully suited to and, judging by his frequent laughs, a life he thoroughly enjoys.

"Driving is fun, but there's nothing like keeping people happy," he says, speaking of fans and sponsors alike.

Neuenberger once owned gas stations and a fleet of tow trucks. But he sold his businesses to pursue racing. And he has no intention of taking his foot off the accelerator any time soon.

His Daytona finish gave him 138 points in his NASCAR class, and his challenge is to continue building that point total in the coming 18 races, beginning May 2. The key to coming out on top of the Goody's year-long championship will be consistency, and Neuenberger believes he has a shot.

Another key is confidence, and Neuenberger gained some with his Friday the 13th finish in Daytona. After nearly 50 races, his is the sort of confidence that comes through television and radio interviews and even through the less speedy medium of print.

He said: "I will win a race this year."

| Back to Archives |

VolumeVI Number 9

March 5-11, 1998

New Bay Times

| Homepage |