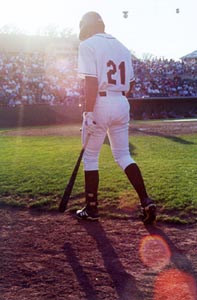

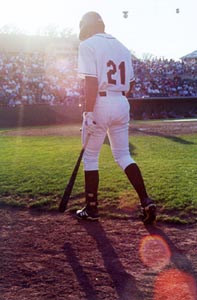

Playing the Game, Chasing the Dream

Playing the Game, Chasing the Dream Playing the Game, Chasing the Dream

Playing the Game, Chasing the Dream

Two Games, Four Lives In Chesapeake Country Baseball

Baseball breaks everyone's heart at some point. If you're not making millions, why keep the faith with a game that can frustrate the patient and shatter the dreams of the innocent?

by Christopher Heagy

photo by Mark Burns

In 1982, I was eight years old and the Orioles lost the pennant.

After a tight race with the Milwaukee Brewers, the season hung on a four-game

showdown at Memorial Stadium. Three games back, the Orioles needed a sweep

to win the American League Eastern Division. The Orioles took the first

three. Only a Sunday victory stood between the Birds and a trip to the playoffs.

With ace Jim Palmer on the mound, I believed with all my might that the Orioles would win. The Brewers ended that hope, early. Robin Yount led the charge that defeated the Orioles and broke the heart of an eight-year old in Upper Marlboro.

The tears flowed; my dreams were crushed. I moved every baseball card, pennant, jersey, glove, ball and poster into my sister's room. I told my family that I had given up on baseball. It wasn't worth the heartache.

I lasted three days without baseball. I tried my best, but I couldn't do without it. The pictures and pennants went back on the wall as dreams of game-winning grand slams in Oriole orange returned.

I grew up on baseball. I bought baseball cards and memorized the stats. I followed the standings every morning and listened to the games on the back porch every night. That's the way it was. With the passion of youth, I loved the game.

I played baseball for 17 years, no matter what. Every spring, as baseball returned, I couldn't contain my excitement. I knew it was rare for big league dreams to come true, but I held onto them anyway.

I played through little league, high school and college. I played for pleasure - and something more. Baseball gave me a dream and a secret identity. I thought of myself as one of the eccentric lefties that are part of baseball folklore.

I still remember the last time I pitched. In the spring of 1996, against Rider College, I gave up six runs in three and a third innings: Not what I had hoped for in my last game. Baseball is not a kind game, and the last year of my baseball career had not gone as I would have liked. My team could never put a string of wins together. It seemed like we found ways to lose ball games.

The season left a bad taste in my mouth, and for the first time I was glad when a season ended. I couldn't even say that I was sorry my baseball career was over.

Before that terrible season, during fall practice my senior year, my friend Scott and I had been stretching in the outfield. Scott seemed to know what we would be losing, and he said, "Let's try to enjoy every beautiful day, each blade of grass, all the warm breezes, each pitch, practice and at bat. This is our last time around. We'll probably never have the chance to do this again."

I wanted to enjoy it all, but I couldn't see what Scott saw. I never

really thought about this being the last time. The finality of the season

never set in. There was always baseball. I took it for granted.

I haven't touched a ball since that day in May.

I don't follow baseball like I did when I was a kid. My baseball card days are over. I glance at the standings every now and then, but I no longer shed tears for Orioles' losses. I don't have that many tears. The passion of youth has faded. Sometimes I miss that passion.

When I started writing this article about local ball, I wanted to find great games and fields. But I wanted to find more: I wanted to look at the men who have made this game their life. The men who every spring and summer return to the ball park to chase after a ball and play a child's game.

What brings them back to this game that can frustrate the patient and shatter the dreams of the innocent? Baseball breaks everyone's heart at some point. Yet these men return, play again, take more heartache and continue to reach for their dreams.

More than anything, I wanted to search for a game that was such an important part of my youth and part of my identity for so long. I wanted to find a passion I lost and a game I loved.

photo by Brittanie Oakley

Sunday's Baseball Heroes

Chesapeake Swampdawgs vs. Tracey's Twins

"My wife wanted me to take her to the horse track today," exclaims one old-timer. "I told her no, I'm going to the ball game."

A Sunday game between the Chesapeake Independent League's Chesapeake Swampdawgs and the visiting Tracey's Twins brings an assortment of characters to the recently completed Swamplex.

Sweltering is the only word to describe the feel of this day. The July 4 sun beats down on the field. At the Swamplex, off Bayfront Road in Deale, the limp flag in center ends all hopes that even a slight breeze might offer relief. As the 3pm start approaches, the sun is high in the sky, and shade is still a dream.

Bill LaPerch

photo by Brittanie Oakley At 42, pitcher Bill LaPerch relies on experience and his mental power to compensate for his lost speed and growing years.

"I hope I can get two or three innings in today," 42-year-old Swampdawg starter Bill LaPerch says as he walks by. "Every four or five pitches I have to stop to get my breath, and I can never seem to catch it."

This is a heat that nightmares are made of. The air is so humid you can see the suspended moisture, but the only water is the sweat dripping down your forehead.

But somehow this heat feels just right. This is baseball weather. The chilly spring days, with their long sleeves, tight arms and stinging hands are gone. This heat lets the hitters show off the biceps and forearms that make the bat crack and the ball jump. Pitchers can stretch out and reach back for that extra juice.

And for the fans, the heat makes the beer seem that much colder.

Bill LaPerch heads to the mound to start the game. He winds up and drops down and flicks the ball to the plate. His side-arm delivery disguises his velocity. Movement offsets the speed he has lost over the years. His mind makes up for what his body can no longer do.

"It's funny how much you learn about pitching when your body is half broken down," LaPerch laughs.

The Chesapeake Independent League has been playing every Sunday for 24 years on privately owned ballparks. The league is a collection of former major and minor leaguers, current and ex-college players and high schoolers hoping to refine their skills. The players are not paid but the competition is intense. The top eight teams make the playoffs at the end of a 20-game season. The championship is decided in a three-game series in October.

Bill LaPerch has played every Sunday for 16 years for the league that introduced him to Chesapeake Country.

"I was living in Greenbelt and playing down here," LaPerch explains. "Every time I crossed the Patuxent River, I just felt better. I realized what a great place this area was. When I had the chance, I moved down here."

LaPerch catches his breath somewhere in the heat and finds his groove in the first inning, setting down the Twins in order.

The Swampdawgs jump ahead on a solo home run down the left field line in the bottom of the second. The Twins tag LaPerch for a solo home run of their own in the top half of the third.

Both pitchers find their rhythm and settle into a groove.

The game picks up pace. The pitchers are throwing strikes and getting ahead in the count. The defense behind both pitchers is solid. In the bottom of the third, with a man on third and two outs, a Swampdawg hitter sends a ground ball into the hole between third and short. The shortstop ranges over, backhands the ball, plants and fires the ball across the diamond, getting the runner by half a step and saving a run.

Fans file in, and the sounds of baseball are everywhere.

"Don't help him. Don't help him. Bill is full of balls," yells one old timer after a Twin's hitter swings at a bad pitch.

"That boy is running with a refrigerator on his back," jokes another as the runner slides into third.

And, of course, someone is always unhappy with the umpire.

"Come on blue, that ball was down below his shin," comes the whine as strike three is called.

Maybe it's the holiday or that the Swamplex and Geno's Field, the home of the Twins, are so close. Or maybe this is what Sundays in the Chesapeake League are like. The game has the feeling of a picnic. Everybody knows each other. Fans mingle easily, meeting, laughing and enjoying the game.

Kids are roaming around playing ball or soaring on the swing set behind the third base dugout. It seems you meet old friends or make new ones at every turn. It's a contagious atmosphere with the game at the center.

The Swamplex was built on a cornfield. Surrounded by trees, the diamond was not cut out of the woods. Much like an old city ballpark, this field was built where its surroundings allowed. Instead of building around streets and buildings, the Swamplex was nestled in a clearing.

"When I decided to build this field, everyone thought I was crazy," owner LaPerch recalls. "I thought it was the perfect combination. I needed room for my animals to graze, so I had to fence the property in anyway. We had a flat open space, so we planted grass and built the field. The animals still graze there, so it has worked out really well."

It's a pitcher's park at heart. The thick infield grass slows down hard ground balls. Center field is a cavernous 395. But more deadly is the 385-foot power alley in left center. It's Death Valley for fly balls. A ball has to be crushed to clear the wall.

Hitters can find a couple advantages. With woods so close, the fence surrounding the field leaves little foul territory. There's no hope for a cheap foul out, and not many outs come easy. Right field is the place to drive the ball. It's 322 feet down the line. But the real danger is in right center. The power alley there is only 340 feet away.

Finally, in the bottom of the seventh, the Swampdawgs break through. They use a home run, a single, a bunt and a hit batter to push two runs across.

In the top of the eighth, LaPerch gives up a one-out single, and his day is done. The heat has taken just about everything out of him. His day lasted longer than the two to three innings he had expected.

LaPerch's career, too, has lasted longer than he thought it would. During college, he tore his rotator cuff. Unable to throw without pain, he had to put the ball away.

He tried other games but tired of them. "I played softball and I hated it. In softball, everyone thinks they're a superstar. I missed the skill level and competition of baseball," he tells me.

But LaPerch played softball without shoulder pain, so he figured he could probably play baseball again. He perfected his side-arm delivery and headed back to the mound. He just wanted to play the game he couldn't get out of his system.

"This is not an ego thing. I don't need to do this. It's a team game, but you still have to prove yourself individually. I still get excited on game day. It starts the night before. It's a feeling you can't replicate anywhere else, kind of like going on a first date. That feeling keeps me coming back."

Larry Mulloy

Larry Mulloy

photo by Brittanie Oakley Pitching for the Swampdawgs, "it's just you and the catcher's glove," says Larry Mulloy.

Relief pitcher Larry Mulloy enters the game in the top of the eighth inning. Like LaPerch, Mulloy is a long-time veteran of Sundays in the Chesapeake Independent League. Like LaPerch, he put the ball away but found a way back to the game.

Mulloy gave up the game to concentrate on his college work load. He tried other games but couldn't stay away from the ball field.

"I missed the competition," Mulloy explains. "I grew up playing the game and I love playing. I had to get back in it. I've been playing so long I don't always get the butterflies, but going to the mound is still one of the most enjoyable things in the world. The surroundings disappear, and you reach a level of concentration where its just you and the catcher's glove."

The Swampdawgs close the game out in the bottom of the eighth. They score fivemore runs to make it 8-1. The Twins make the game close with three in the top of the ninth, but the Swampdawgs end the day with an 8-4 win.

After the game, the Swampdawgs head to the pool by LaPerch's house, swap tales about the day, savor their eighth win in a row and look forward to another Sunday in the Chesapeake Independent League.

Mulloy hopes these Sundays will be part of his life for a while longer.

"I plan to play as long as I can get people out," Mulloy said. "I got married a couple of years ago, and it was part of my pre-nuptial agreement. Baseball stays."

The Chesapeake Independent League is a reminder of a time when every town had a baseball team. Local players would work all week and play on the weekends. The games turned into community events and marked the passing weeks.

The Chesapeake League is good baseball. The games are competitive and the players know how to play. Fans can get close to the game and hear the catcher's glove pop, see the outfielders panting after running down a long drive and cheer for their home team.

The best baseball days are behind many of the players in the league. These men might have seen their peak, but their fire still burns. They play hard and they still enjoy the game. And Sundays in the Chesapeake League make regular men the Sunday's baseball heroes.

Bowie Baysox vs. Erie Sea Wolves

Prince George's Stadium, home of the Eastern League Bowie Baysox, is a temple. The grass is bright green. The burnt orange infield dirt is silky smooth. The stadium is not as big as major league parks, but the diamond looks just as perfect.

photo by Mark Burns After 23 years in the majors - 13 as a player, with two trips to the World Series, and four as a coach, with a World Series win with the 1988 L.A. Dodgers - Joe Ferguson, number 13, now wants "to teach the game and give my knowledge back."

Joe Ferguson

"The game is the same as when I played in the minor leagues," explains Baysox manager Joe Ferguson. "The only difference is the parks and the facilities. Minor league stadiums today are better than many of the fields I played on when I was in the big leagues."

It's 3pm. More than four hours before the start of tonight's game, Joe Ferguson is on the field. Dressed in black shorts and a white T-shirt, the 52-year-old manager is trying to stay cool in the mid-afternoon heat.

He's running hitting drills and throwing extra batting practice for two of his players. The crack of the bat echoes through the empty stadium. Cleaning crews are picking up the remnants of last night's crowd.

Joe Ferguson is watching every swing. After each cut, he reinforces the lesson. His hands out, he speaks with his body. Bending at the knee, turning the hip, swinging through the ball, he demonstrates each point. In baseball, there are so many ups and downs, but here is the consistency, here is the routine. Teaching on a warm July afternoon. Working with young players in AA, hoping to reach their dreams.

Joe Ferguson spent 13 seasons as major league baseball player. He came up with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1970. He also played for the Houston Astros, St. Louis Cardinals and California Angels before his career ended in 1983.

Ferguson went to two World Series with the Dodgers. The Dodgers lost both, but Ferguson remembers the joy.

"Playing in the World Series was like my first little league game when I would sleep in my uniform. During the World Series, I couldn't wait to get to the park. I was so excited. I couldn't sleep the night before the game. For me, there was no pressure. If you enjoy the game, there is no pressure. You have expectations of yourself but no pressure."

After the early drills, Ferguson returned to his office to finish preparations for the Baysox's night game against the Eastern League's Southern Division-leading Erie Sea Wolves. The 12 teams in the Eastern League are split into two divisions. The top two teams in each division qualify for the postseason.

The Baysox have been in first or second for most of the season. A short skid has dropped them to third place, but with a record of 50-39 the Baysox are only half a game out of first place. As the season reaches the All-Star break, the midpoint of the 142 game season, the summer pennant race is heating up.

With both teams battling for the playoffs, they are jockeying for position before the first half of the season ends.

The crowd is still filling in as the game starts. Each Bowie starter is announced and is joined at his position by a member of a local Little League team. The National Anthem rises, and the pitcher throws his last warm-up pitch. A surge of energy ripples through the crowd at the first pitch.

In the bottom of the second, the Baysox use a hit batter, a single, a Sea Wolf error and a ground out to put two runs on the board. The Sea Wolves answer back in the top of the third. Back-to-back doubles with two outs pull them within one run.

The Baysox add a solo home run in the bottom of the third, but a Sea Wolf home run in the top of the fourth makes it a 3-2 game. The pitchers silence the bats for the next few innings, and the game moves quietly along.

Well, maybe not quietly.

Baysox baseball is more than a game. It is an experience. If baseball is a kid's game, then all the kids are at Prince George's Stadium. Some are down by the field hoping for an autograph, others are riding the carousel down the right field line. There is a race for every foul ball.

Something is always going on. Between

innings, kids are racing the base paths, T-shirts or hot dogs are slingshot

into the stands, fans are throwing baseballs for new cars or guessing attendance.

Louie, the Baysox mascot, is roaming the stands slapping high-fives, signing

autographs and dancing with fans.

Something is always going on. Between

innings, kids are racing the base paths, T-shirts or hot dogs are slingshot

into the stands, fans are throwing baseballs for new cars or guessing attendance.

Louie, the Baysox mascot, is roaming the stands slapping high-fives, signing

autographs and dancing with fans.

With fireworks every Thursday and Saturday, guest appearances by the Flying Elvises, hot dog eating contests and '70s' Disco Lives Again Night, there is entertainment for everybody.

And there is always the game.

In the top of the seventh, the Sea Wolves threaten to tie. With one out and a man on first, a pick-off throw gets away from the Baysox's first baseman. The Baysox pull the infield in to save a run. A hard ground ball to the shortstop forces the runner to hold. But with two outs, an infield single off the pitcher's glove scores the tying run.

Joe Ferguson is in his third season as manager of the Bowie Baysox. He is in his 14th year as a coach. After his playing days were over, Ferguson coached in the major leagues for 10 seasons with the Los Angles Dodgers and the Texas Rangers.

"I was lucky. I love the game," Ferguson said. "I had the opportunity to sign professionally, and I had big league abilities. I made my living in baseball for 17 years. After that long, it's tough to switch careers. The game is tough to leave. We are all highly competitive and yearn for the competition. But the routine of baseball is tough to give up. The lifestyle: It becomes a life within your life."

Ferguson was a coach on the 1988 Los Angles Dodgers. He was on the bench for Kirk Gibson's ninth-inning home run that won game one of the 1988 World Series for the Dodgers.

"It was one of the most electric moments in Dodger history. That home run turned the momentum and gave us the confidence to beat the Athletics. We knew they had the big bombers, but we believed we had the pitching to beat them."

Ferguson has played in the major leagues. He reached two World Series

as a player and won a championship as a coach. He has lived dramatic moments

and survived tense situations. He has reached the highest levels of this

game. He has remained a baseball man throughout, clear about what a great

ride it has been and what the game still has to offer.

"My goal is not to get to the major leagues as a manager," Ferguson said. "I was there for 26 years. I just want to teach the game and give my knowledge back. No one gets rich down here. But that's not why we play the game. Work is foreign to the baseball player. I want to do what I enjoy. I want to have fun with the rest of my life."

The crowd is getting nervous as the tie game heads to the bottom of the eighth. Down the third-base line, a group of young fans begins a home-run chant. A deep fly ball to the gap in left bounces off the top of the wall, inches short of granting the fans' wishes. The drive turns into a triple.

A clutch two-out single to center scores the go-ahead run. The Baysox lead 4-3.

The Sea Wolves try to rally in the ninth. A single and a walk put runners on first and second with two outs, but a high fast ball and a swinging strike three end the threat and the game.

The home fans head to the exits happy. The Baysox win.

For Joe Ferguson, it's one more game in a long season. It's one more win in a long career. As the game fades into the night, he's making plans for the next game. The cycle continues. The routine of the game goes on.

above photos by Mark Burns Kids gather at Baysox games not only to watch the action but also to catch pop-fly foul balls and to hug Louie, the team's friendly, green mascot.

Terry Rosenkranz

photo by Mark Burns Many

minor league players don't make enough money from baseball to survive. "I've

tried to walk away," says Terry Rosenkranz, who owns a Florida nightclub.

"Baseball is like an addiction."

Terry Rosenkranz, a 28-year-old left-handed relief pitcher, has been chasing his big-league dreams for seven years. He was drafted by the Texas Rangers in 1992. He pitched in the Ranger and Milwaukee Brewer organizations. Rosenkranz even headed to Taiwan to play ball.

For some top prospects, baseball can pay the bills. Many more have to juggle jobs in the off-season to maintain their baseball lifestyle. Rosenkranz owns a night club in Kentucky, where he works in the off-season.

You never know where the game will take you next year - even this year. You don't make enough money to survive. Your lifestyle is nomadic, alienating family and friends.

Baseball is frustrating. It has frustrated Rosenkranz. But the game keeps him coming back.

"I've tried to walk away," Rosenkranz admits. "There have been times when this game has frustrated me so much I'd sit on my couch in the winter and say, 'I'm done, I'm done, I'm not playing any more.' But then I'd flip on the television or hear something about baseball on the radio, and I'd be ready to go again. Baseball is like an addiction."

Failure and frustration are part of baseball. It seems that for every success, there are setbacks. For every home run, there's a handful of strike outs. For every shutout, there's a five-run inning. But the taste of success pushes you to try your luck again and to hold onto the game.

"It's the whole atmosphere," Rosenkranz explains. "Hanging out with the guys before the game, coming to the ball park, the energy and excitement. Then you come in a situation where the game is on the line. It's a rush, the energy just hits you. No matter what has happened, I always believe that I will come out on top."

That belief keeps Terry Rosenkranz coming back to the ballpark each day. That belief has him looking forward to baseball each spring.

The Bowie Baysox are what minor league baseball has become. The game is at the center of a large package of entertainment. They play in a beautiful stadium, on a perfect field. The game has a big-league feel.

Part of the attraction is that some of these boys could be the major league stars of tomorrow. Fans can say they saw a future star first.

But these players have already made it further than most, and the jump to higher levels is tough. Many of these players will never make it.

These players are still chasing after the dreams that many of us had when we were younger. They are close, but they are still struggling with a game that can turn dreams to nightmares at any time. But it's a dream that's tough to get out of your head.

What We Love in The Game

The views from AA to independent leagues might look different, but the men involved in the game look alike. A love of the game runs through each of them. Something about the game continues to bring them back each year. Following the games over the past few weeks, I understand what I miss about baseball.

I miss hitting fungoes during batting practice, hanging out in the bullpen and gripping a 3-2 fast ball.

I miss the smack of the bat, the tension of the bottom of the ninth inning when your team is one run behind, the sheer joy of a grand slam and the relief of an inning-ending double-play ground ball.

There is no better feeling than when your team wins and, for at least one day, your baseball dreams come true.

That's what I was looking for. I wanted to miss the game and realize why it was so important to me. Maybe I have lost some of the zeal of youth. I might never have the passion for the game that I did at eight again.

But I forgot how much I enjoy the game for the game itself. No matter who's playing, a ball game is a great way to spend a summer afternoon.

The other day I went out and had a catch. I just wanted to know what it was like to throw the ball again. It felt good.

Where and When They Play

Prince George's Stadium is located just south of Route 50 at the 301 South exit. The Baysox return home for a three game series against Akron on July 19, 20, 21. Call 301/805-2233 for ticket information.

The Chesapeake Independent League continues on Sundays throughout the summer. Chesapeake Swampdawg home games are played at the Swamplex just off Route 268 east just at Franklin Gibson Road Homegames are July 18 and Aug. 8 and 22. The playoffs begin in September.

Also at the Swamplex, The Chesapeake Christian Athletic Association offers a free baseball clinic for 8-, 9- and 10-year-olds. The clinic runs Wednesday nights from 6-7:30pm for the rest of the summer.

For Bill LaPerch passing on his knowledge of the game is the best part of the field he created. "There is nothing better than showing a kid how to do something they couldn't do before," he says. Bring your young ballplayer to the clinic and meet some of the men of the Chesapeake Independent League.

| Issue 28 |

Volume VII Number 28

July 15-21, 1999

New Bay Times

| Homepage |

| Back to Archives |