Sporting Life

Water Wolves of the Tidewater

By Dennis Doyle

It had been a pleasant morning despite the 40-degree temps. We had been fishing the Pocomoke River near Salisbury for yellow perch and were having heartwarming success despite numb fingers and tingling toes. I think they were tingling but feeling in any of our extremities was problematic. We hoped the brightening sun would prove at least a partial remedy.

Then my brother Bill’s rod slammed down and his drag began to sing. He at first looked perplexed, none of the fish that morning—while spunky, indeed—took out much drag. This one, however, was headed for a distant shoreline and wasn’t intending to stop short of it.

“I’m guessing pickerel,” someone said.

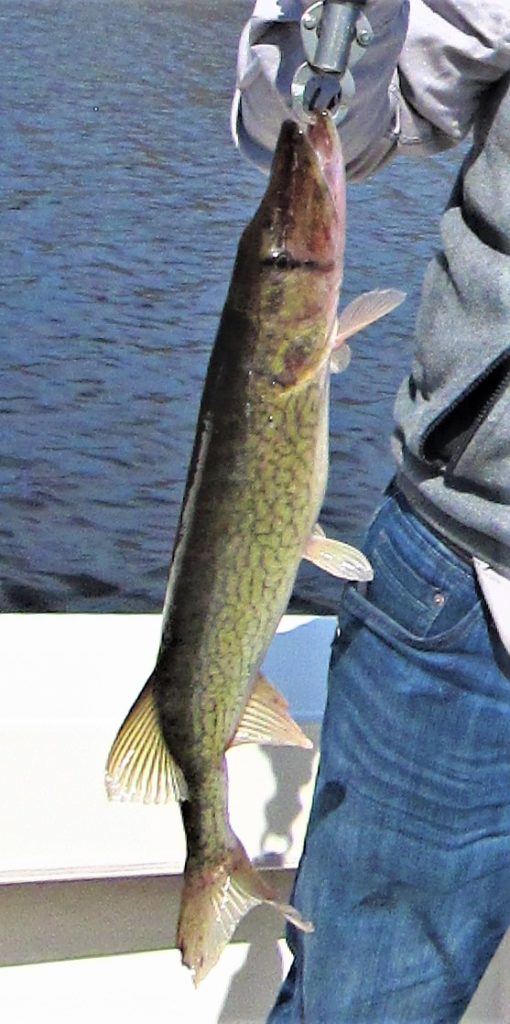

About five minutes later a long, iridescent green shape slowly emerged from the depths, burst open the water next to the boat then once again disappeared for a long minute or two. Eventually, we netted the sizeable fellow: a 23-inch chain pickerel, flashing needle-like teeth in a duck-like mouth and muscular, chain-link patterned flanks.

The water wolf is one of the many aliases given to this very special winter sport fish, the chain pickerel. Known by many monikers throughout its range and sometimes confused with the walleye pike in the Northeast, this predatory fish is resident in the eastern U.S. all the way down to Louisiana. And it seems to become more active the colder it gets.

Inhabiting creeks, rivers, ponds, lakes and impoundments the jack pike, grass pike, or chainsides, tolerates brackish water though it avoids the Chesapeake Bay proper and resides only in the medium to upper fresher waters of its tributaries.

A cousin to the northern pike and muskellunge with a 14-inch minimum legal size and a 10 fish limit, the slender but powerful gamester can reach 36 inches, but generally, any fish in the 20s is considered a good one, and a 25-incher wins a citation.

An ambush predator, the fish prefers lurking near laydowns and blowdowns (trees), old piers, docks and submerged or floating vegetation. They will attack appropriately sized spoons, spinner baits, crank baits and surface plugs, as well as streamers, popper flies, soft plastic frogs and lizards. Traditional live bait presentations involve a lip-hooked bull minnow under a bobber and either slow-trolled behind a small boat, kayak or canoe, or cast and retrieved from those craft or the shoreline.

Medium to lightweight tackle with up to 10-pound test is preferred, as this fish can then show its battling skills; they are an athletic adversary. Armed with sharp, pointed, holding teeth rather than cutting dentures, a piece of 15- to 20-pound mono or fluoro will be adequate to prevent cutoffs.

A net is mandatory for landing the pickerel, not only because of its teeth but because lacking scales, it has a strong coating of protective slime that makes it almost impossible to grasp with a bare hand. Managing the fish carefully in the net so as not to affect its coating is also strongly advised to increase survivability upon release.

Only the quantity of small bones found throughout its body keeps the pickerel from becoming excellent at the table. It’s virtually impossible to get a boneless filet without losing an unacceptable quantity of meat. However, anyone with patience and a taste for good seafood can pick through a cooked fish, discarding the bones and then, mixed with egg and bread crumbs, creating fish balls or patties browned in peanut oil or Crisco and served as finger food.

They’ll not be sorry, its firm white meat is sweet and succulent.