The Face of Protection

Our great-grandmothers rolled bandages; we’re sewing masks to help those on the front lines

When a nursing friend in Baltimore asked me to sew a few facemasks for herself and a few coworkers, I felt an adrenaline rush of usefulness. Using a lifetime’s worth of project scraps from baby clothes to curtains and upholstery, I whipped up 13 in the first day and posted a photo on my Cape St. Claire neighborhood Facebook page. Within minutes I had a deluge of comments ranging from order requests to tips from other seamstresses already engaged in the same pursuit. Within three days, my tally was up to 45; I dropped my average production time per mask from 25 to 15 minutes; and I had three donations of materials and four new sewing friends.

On March 3, the World Health Organization warned of a “severe and mounting disruption to the global supply of personal protective equipment caused by rising demand, panic buying, hoarding, and misuse.”

On top of the mounting coronavirus pandemic, recent wildfires depleted inventory to the point that the American Health Care Association estimates 40% of suppliers will be out of stock by April. Suddenly America is relearning what it means to Use it up, Wear it out, Make it do or Do without, as the Greatest Generation would say.

N95: The Superhighway of Defense

The N95 mask is so efficient the FDA calls it a respirator. Density and snug contouring combine to block at least 95 percent of tiny (0.3 micron) test particles. If properly fitted, its filtration far surpasses that of ordinary facemasks, yet there is no guarantee against infection.

Across the spectrum of lesser alternatives, a surgical facemask is a looser barrier against contaminants. Cloth masks sewn from double layers are similar but with the advantage of being washable, and some include a pocket for added filtration such as tissue. Finally, there are the pre-shaped dust masks common to the construction and gardening industry. So, how do they stack up?

In 2010, when SARS was on the horizon, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health conducted a study comparing the N95 to the surgical facemask, the dust mask, and a folded bandana. Using a saline aerosol contaminant, the N95 was found to be 89.6% effective, followed by the surgical mask at 33.3%, the bandana at 11.3%, and the dust mask at 6.1%. Their conclusion cautioned against the false sense of security that any of these shields may instill.

So Who Needs One?

It depends on who you ask. “Every person in the United State who is going out of their home should be wearing a mask right now,” says Dr. Sun Hope, host of The Million Mask Mayday how-to video.

But Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases took issue with this philosophy, saying masks not only offer a false sense of security but also cause people to touch their face more often in order to adjust them.

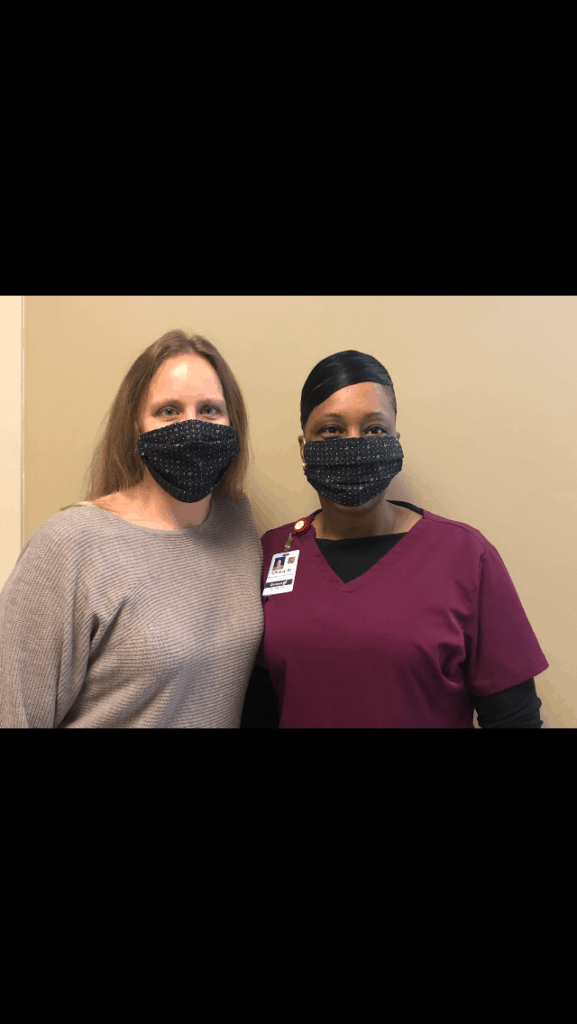

Masks remain a vital part of healthcare workers’ personal protective gear. So getting them into their hands is critical.

Nurses are reusing hospital-issued N95 masks and preserving them with homemade cloth models. The Center for Disease Control does not yet have a protocol regarding facemasks, yet Anne Arundel Medical Center has issued a call for homemade masks (deliverable to the South Pavilion loading dock between 7:30am and 3pm daily).

In Baltimore, the Mayor’s Office of Performance and Innovation provides a link for mask-sewing volunteers at Johns Hopkins Hospital (www.signupgenius.com/go/60b0c4cafaa2ca0fa7-covid19).

The Baltimore Washington Medical Center says they are OK for right now but in a week or so they may have to expand their call for donations of the medically-approved N95 to include home-sewn models.

The pattern I’ve used calls for two 7×9” swatches of fabric per mask and two 7-inch strips of elastic to hook over the ears. Sew right sides together, invert, pleat, and topstitch. Nurses have told me they prefer elastic because it’s faster to put on but some stores may be low on supplies so they can be made with fabric ties as well.

Sara Cusate, a relative newbie to sewing, lost her first morning to YouTube instructional videos on how to fix her grandmother’s machine. She also got involved at the request of a nursing friend. “I’m a total beginner but am crafty,” she said that first day, “so I can figure most things out.”

She now has 24 masks in-progress with her eye on a grand total of 50. Alice Conover, after sewing 27 masks, is switching to surgical caps at the behest of respiratory therapists.

The benefits, beyond community service and camaraderie, are visceral. Sewing is a Zen experience that demands laser focus; all that matters is the seam, the pleat, the ear-loop of the moment, shuttling back and forth between the machine and the ironing board.

“It felt great to not really think about what’s going on for a little bit,” said Cusate after her first day. She’s not sure yet who she’s donating to other than her nurse friend who plans to wear them over the hospital-issued N95 in order to keep it clean for reuse.

The response from the recipients has been heart-warming and I plan to continue as long as my machine and my supply of elastic (or hair bands) holds out. Lessons learned so far: #1 tightly-woven cottons work best. #2 Denim, quilting, and vinyl are awesome for protection but brutal on the machine I bought 38 years ago to make my wedding dress. #3 Triaging order requests is, sadly, a reality; some people seem to think I’m running a fashion boutique.

Joann Fabrics is currently providing free materials and tutorials for facemask sewers: https://www.joann.com/make-to-give-response/ and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgHrnS6n4iA