|

|||||||||||||||

|

Volume 12, Issue 25 ~ June 17-23, 2004

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Silvio and Rafael didn’t learn that until they had been out in the Florida Straits, in the middle of hurricane season, for three hours. Like so many in the flotilla, they had met their companion in Miami. Like all of them, he was crossing to bring his family back to the states. In that desperate time, strange alliances were formed. Silvio and Rafael had a boat but no money for gas. The stranger had gas money and sailing experience. He hadn’t lied about the gas money, although to this day Silvio wishes he had. Silvio and Rafael had bought a 27-foot Wood Owens with a 283 Chevrolet engine. But its tank held only 20 gallons. The three men had to buy two 55-gallon drums to fill with gas to make the 90-mile trip to Cuba. Then, one of them would have to man the tank to make sure they had enough. No good could come out of running out of gas. Before setting off for sea, they flipped a coin. The loser would be responsible for siphoning the gasoline through a hose and into the gas tank. The winner would man the compass. Sick from gasoline and rough seas, Silvio discovered another problem when he went to lie down in the cabin. Cockroaches. The wooden craft in the soupy Florida humidity had lured cockroaches. Silvio’s vomit-stained clothes and puddles on the floor brought them out of hiding. At that time, even with his father waiting for him in Cuba, the waves and the roaches and the gasoline were too much. Silvio wanted to die. Going Home In 1965, in response to growing pressure from exiles in the United States, Fidel Castro stood in the Plaza de la Revolucion — Revolution Plaza — and announced to the world that no one was being held in Cuba against their wills. “Mis compadres. I’m not keeping anybody here. If you want your family, come get them,” he had proclaimed. This was four years after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. This was three years after the Peter Pan Airlift, when 14,000 Cuban children were sent to the States to live by themselves. Silvio’s two brothers had been among them.

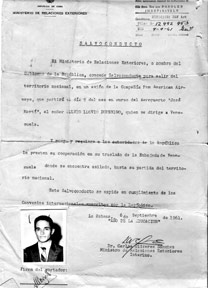

Silvio and childhood friend Rafael took leaves of absence from their jobs in Los Angeles, borrowed $2,200 from friends and family and drove to Miami to rescue their relatives from Cuba. But in Miami they found no boats. Taking Fidel at his word, others like Silvio and Rafael had snatched up every boat, and it was a free-for-all if one went up for sale. So the two friends headed to Naples, a hundred-mile drive through the Everglades on the winding and treacherous Alligator Alley. In those days, if you broke down you waited inside your car baking in the Florida sun and praying that someone would find you before you had to step outside and face the alligators. In Naples, they found a boat and a shipper willing to deliver it to Marathon, an island in the Florida Keys and the closest point to Cuba. Silvio rejoiced. After years of oppression and hardship, his family would finally be reunited. Paying the Price Silvio’s father had committed the ultimate sin. In the spring and summer of 1959, during the dawn of the revolution, his transgression would have put him in front of a firing squad. By November 1960, a kinder, gentler Fidel had emerged. So when Silvio’s father stood up after mass one Sunday and questioned the infallible Fidel, complaining of the people’s lost freedoms, he was stripped of the business he had spent 20 years building and was sentenced to three years in prison. He was lucky not to have been shot. Lucky if that’s what you call spending three years in a Cuban prison, tortured and watching the men around you break, go mad and die. Silvio had been lucky, too, escaping Cuba in 1960 with a visa to the U.S. from an earlier visit.

Five years had passed since he last saw his father. Silvio was 25. He had survived a war, lived through the torment of the Cuban Missile Crisis, married and divorced. He had lost his country. And for all those years, he was plagued by thoughts that he would never again see his father. During those five years, Silvio had almost found his way into a Cuban prison. He had joined with a group conspiring to sneak back into the Cuba and fight the government. What none of the conspirators knew was that one of their group was a lieutenant in the Cuban Secret Service. When the group landed in Cuba, Silvio was still in Miami, left behind, he to this day believes, by the lieutenant, who took a liking to him. In Cuba, the conspirators all were taken into custody and handed 30-year prison sentences. Silvio’s luck held steady a second time, when he joined in the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. He was one of the ragged group of CIA-trained exiles who stormed Cuba to reclaim their country. Instead, without air cover promised by President Kennedy, Castro’s militia repelled the invaders and crushed what little insurgency arose in the cities. The captured exiles were abandoned, Silvio among them. Many were caught, many were imprisoned, and many were killed. Silvio escaped and for weeks ran from the militia, relying on the kindness of farmers, trudging through sweltering swamps, drinking putrid water wrung from his socks. Forty years later, he says that what kept him going those dark days in the wake of the Bay of Pigs invasion was the thought that if he were caught, it would break his father’s heart.

Lost at Sea On a cool morning in November, three hours before the sun went up, 20 boats left Marathon for the 90-mile voyage to the Bay of Matanzas. That they left before the sun was up should have been the first indication that the naval officer in their midst had no idea what he was doing. The second should have been that they left at low tide. They should have known there was trouble when seven of the 20 boats ran aground. Soon another flaw in the plan became clear. Not all the boats traveled at the same speed. Between the rough seas and the lack of seamanship, within an hour and a half, Silvio’s boat was alone. And they were lost. Rafael was the navigator. He knew they needed to head out at 320 degrees, but he never adjusted for the 10-mile-an-hour current. At times they traveled sideways. That’s when they weren’t being sent skyward, the propeller roaring as it rose from the water, on the tops of eight- and 10-foot waves made worse by the wake from the tankers crossing the straits. Silvio held on as long as he could, taking breaks with the cockroaches and riding out his seasickness, until Rafael called him to fill up. Early in the afternoon, with the sun too much to bear even in November, they realized they were lost. But they were too sick and exhausted for their circumstances to sink in. They were in survival mode and, as much as they wanted this to end, they fought on. It was at 4:30pm, almost two hours after they realized their fate, when they spotted the fisherman towing another boat from the flotilla. They fought through the waves to approach. The fisherman had made this trip many times. He told them to follow him, and he would guide them. Within an hour and a half, they could see the mountains of Cuba rising and falling against the horizon. By two in the morning, almost 24 hours after leaving Marathon, they could hear the waves crashing on the shore. Another fisherman joined them and led them the rest of the way in. Seasick and sunburned, they were home. They did not know whether they’d be free to leave again.

The Cuban Coast Guard knew why the bedraggled men were here; boats had been arriving for days. “You’re in the wrong place,” said a captain. Silvio could tell his rank from the insignias on the man’s threadbare uniform. “You need to cross the bay and dock at Camarioca.” Covered in his own stench and exhausted, Silvio shook his head. “Me tienes que matar antes que me meta en ese bote otra ves.” You’ll have to shoot me before I get back on that boat. In Cuba in 1965, that was an option for dealing with disobedience. Another threat loomed as Silvio stood on that dock. The names of the men who had fought in the Bay of Pigs were on government records. The Venezuelan Embassy in Havana, where Silvio had finally found refuge, had told the Cubans he had been there. In Cuba he was still a wanted man. Fidel had missed him the first time. Now he had a second chance. “They knew who I was,” he says. “They had to. But I didn’t care. When you have something you love so much like I love my father, and you know his life depends on you, then you just do it. The guys on the other side knew that and respected you for being there.” The captain stared Silvio down. But he gave in and drove him in a jeep to the other side while Rafael and the sailor got a military escort to cross the bay.

The camp was his home for the next 17 days. Reunion Somewhere in those 17 days, Silvio was allowed to see his father. A friend of the family, Hilberto Monson, made the trip to Silvio’s hometown, Ciego de Avila, a couple of hours drive on Cuba’s crumbling roads, and brought his father back. The father and son were brought to separate ends of a long walkway that ran for more than 100 yards. They could see each other across the long expanse, but they had to walk slowly, under the watchful eyes of the armed guards, to the middle where, for the first time in five years, they would be together. The last time his father had seen him, Silvio was just a boy. Now a man walked toward him, a man who had seen things a father would give his life for his son not to see. Silvio was in for a surprise of his own. Toward him walked a man beaten and broken in body but not spirit. If Silvio had learned anything over the last five years, it was that you can kill a man but you cannot kill his spirit. They met and hugged as only a father and son who thought they had lost each other forever can. They squeezed tight, holding on for dear life and cried. The five years they had lost melted away in the tropical heat of a blazing Cuban sun.

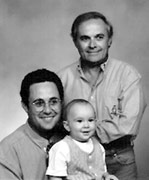

Silvio and Rafael were allowed to leave after 17 days in the camp, but they were forbidden to take their families, instead assured that their relatives would soon follow by plane. Still their boat harbored a refugee — an 18-year-old who worked in the camp — though it meant prison for all of them if caught. Silvio’s father and stepmother arrived in Los Angeles three weeks later on December 15. That Christmas was their first together since 1959. Rafael’s family arrived a week later. Today, Sergio, my grandfather, is dead. But his story lives on in my father, myself and, now, his great-grandson — my son — Duncan. Why did Silvio do this? He wipes away a tear as he answers. “You would do the same. If you are put in a position where you have to do a thing, you do it. You don’t expect these things to happen, but life brings them and you have to do what you have to do. Life goes on.” Getting the Story |

|||||||||||||||

|

© COPYRIGHT 2004 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. |

Family Values

Family Values