|

|||||||||

|

Volume 13, Issue 8 ~ February 24 - March 2, 2005

|

|||||||||

|

|

Maryland’s African American heritage gets a double boost this spring by Carrie Steele It’s no secret that Maryland’s African American heritage is as old as the American state itself. Over the past 400-plus years, stories of injustice and hardship have transformed into tales of triumph and success that Marylanders retell with pride. Come spring, you’ll find two new ways to get acquainted with volumes of black history, both the struggles and the victories. You’ll get inspired by famous Maryland figures — like Harriet Tubbman, Thurgood Marshall, Benjamin Banneker, Frederick Douglass, Leon Day, Eubie Blake and Billie Holiday — and their successes in the face of opposition. You’ll also discover scores of stories, including heroic underground railroad escapes; quilt patterns bearing coded messages; jazz musicians’ journeys to stardom; and pioneering figures who broke through social barriers. The storytellers are Baltimore’s new Reginald F. Lewis Museum of African American Heritage and the expanded Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis. The large, metropolitan Lewis Museum plans a national focus, with special attention to Maryland history. Banneker-Douglass’ more intimate gallery space will continue to bring to life history of Annapolis and beyond inside its historic building and new extension, built on a property with history. Both museums claim they won’t compete, but will rather share resources and work together to spark interest in black history tourism. Old Banneker-Douglass’ Fresh Face “We’ve worked closely with the new museum,” said Elizabeth Stewart, research historian at the Banneker-Douglass museum. “We have a synergy relationship. There’s a lot of great stories to be told.” The Banneker-Douglass collection is the state’s official repository for its wealth of African American material culture. The collection encompasses thousands of artifacts, ranging from wooden African statues to a collection of portraits and photographs of historic black Marylanders to marbles excavated from historic African American neighborhoods. Most are stored at the archeology lab at Jefferson Patterson Park in Calvert County, another and roomier part of the state historic complex. The Banneker-Douglass Museum itself is housed in the old Mt. Moriah AME Church, built in 1875 and later a center for civil rights organizing. Bright stained-glass windows still illuminate the gallery space. Space now is limited, with exhibits on the sanctuary’s upper-level and lower-level walls, so only a small part of the collection is on display. Nowadays, that’s a cast-iron Harriet Tubbman, along with story boards to tell of her escape from slavery and assistance to other fugitives. You’ll learn about how quilting patterns sent messages to slaves escaping to freedom; glimpse the old Mt. Moriah AME church that used to hold services in the sanctuary; and view part of a black and white photograph collection by Thomas Baden, who documented Annapolis’ African American community during the 1950s and ’60s. All this and more rests in Banneker-Douglass’ present space, which has a quiet, reverent feel that allows you to linger by stories and exhibits. “We get a good mix of local and out-of-town visitors,” Stewart said. “And we’re a resource for local schools.” Opening the first floor in May and the entire building in the fall, Banneker-Douglass’ new building doubles both gallery and office space. “When our new building opens,” Stewart said as she motioned to the high ceilings of the church-sanctuary-turned-exhibit-hall, “this space will be perfect for performances and programs because of the acoustics.” When doors open, one permanent and one temporary exhibit will draw you in and keep you coming back. The permanent exhibit, Deep Roots, Rising Waters, overviews black history in the Chesapeake region and includes artifacts from local benefit societies; a fireman’s hat from the late 19th century; and an original invitation to Frederick Douglass’ funeral. Artifacts in the other, temporary, exhibit couldn’t be more local: They were found on the very lot that houses the new building, and include pottery, bottles and toys from the 1890s through the 1940s, recovered from two summers of archeology digs. Exhibit designers will swap temporary exhibits roughly every six to nine months. Next year’s visitors will most likely see a quilting exhibit.

In Baltimore, the all-new Lewis Museum doesn’t have the history of Banneker-Douglass, but it has size, location and backing. The Pratt Street address is donated by the City of Baltimore, for a 98-year, $1-a-year lease. The museum remains a private, non-profit corporation, named after Reginald Lewis, a Baltimore-native lawyer who became CEO of TLC Beatrice International, a billion-dollar company and spoke to business audiences nationwide. Supported by funding from both state and the private sources, the Lewis Museum was created after a study ordered by former Gov. William Donald Schaefer revealed a void in the preservation of historical sites, objects and oral histories. It’s envisioned as drawing tourists from around the country. The new $34 million, 82,000-square-foot museum will be the nation’s second largest museum dedicated to African American history, smaller only than one in Detroit. Plans forecast 300,000 visitors opening year and half that in subsequent years. The museum’s mission is “to be the premier experience and best resource for information and inspiration about the lives of African American Marylanders.” As you walk through Baltimore’s new museum, you’ll find three main exhibit themes: First, Family and Community shows how the African American family and community groups have provided and still serve as a support system in the face of oppression. Second, Building Maryland, Building America presents over two centuries’ worth of stories, focusing on the labor of enslaved Africans in Maryland. Third, you’ll find notable African Americans who transcended circumstance to live their dreams in music, art and writing in Art and Enlightenment. Combining to dramatize 350-plus years of African American history are re-created environments, artifacts, photo murals, audiovisual programs and interactive experiences, including an oral history recording and listening studio — plus presentations in a 200-seat theater and thematic programs. Since Lewis is the new kid on the block, its older and wiser neighbor, the National Aquarium in Baltimore, is helping orient the staff. The Lewis museum is scheduled to open June 25 with a grand opening and dedication by the governor. On the eve of the opening, Johnny Mathias sings African American history at the Meyerhoff. Banneker-Douglass will have a “soft opening” of its temporary exhibit on the first floor May 14; its grand opening of the entire building is set for fall. Both Lewis and Banneker-Douglass are parts of the Consortium of African and African American Museums in Maryland, a network of nine cultural centers and museums. But the story of Maryland’s black history reaches far beyond museums to historic houses, churches, parks, graveyards, historic markers and sites — ranging from Harford County’s 1867 Hosanna School, the first public school for African Americans in the country, to the Black Solider Statue in Baltimore. These and more are the treasure troves of heritage to be reopened generation after generation. Reginald F. Lewis Museum, 830 East Pratt St., Baltimore: 410-333-1130; www.africanamericanculture.org. Banneker-Douglass Museum, 84 Franklin St., Annapolis: 410-216-6180; www.marylandhistoricaltrust.net/bdm.html.

New Bay Rx: Finish What We Start New Bay Rx: Finish What We StartExisting programs, better monitoring might do wonders, scientists say by Sandra Olivetti Martin When scientists get together to talk about the Bay, they don’t waste words on ideas bright, new or costly. In these days when chronic wasting disease on the Bay side meets chronic penury on the dollar side, they’re not asking for more money. They’re not even asking for much more science. They’re asking that what we start, we finish. “I think an effective approach is to align [existing] policy on state and national levels with restoration goals,” Center for Environmental Science professor Donald Boesch told the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. So the big news from Bay scientists wasn’t so big. With some ten thousand scientists gathered in Washington, D.C., to share their research, Bay scientists were talking plain old-fashioned follow-through. For a long list of troubles on the Bay, scientists Boesch, Margaret Palmer and Robert Howarth had in-hand remedies. Unfinished business on Bay-feeding rivers and streams was the worry of Palmer, an aquatic ecologist who lives in Davidsonville and is Boesch’s colleague at the University of Maryland. “The good news,” she said, “is that there’s more stream and river restoration in our Chesapeake Bay watershed than any other place in the nation.” Since 1990, $426 million has been spent on restoring our streams and rivers. Those millions have meant the reestablishment of healthy living riparian zones, effective stormwater management and stabilizing stream and river banks. You know, of course, that the good news lead-in always means bad news to follow. On the followup activities of assessment and monitoring, Maryland falls to the bottom of the class. Thus, said Palmer, “We do not know what methods to use because we haven’t evaluated our efforts.” The remedy? “To learn what’s most effective, we need to invest in monitoring — for which costs are trivial compared to costs of implementing restoration efforts,” Palmer said. From our knowing and doing what works, Palmer said, “streams would be properly restored, and clean water would mean more fish and increased biodiversity: All good things going to the Bay from its lifeblood of streams and rivers.” For Boesch, the missing followup is “aggressive actions under existing authorities.” Thus, he said, we’ve got the tools to clean up the Bay in the federal Clean Air Act and farm bill and Maryland’s flush tax. Using the farm bill effectively for Bay restoration, for example, would mean “transitioning agriculture subsidies from production to incentives for environmental outcomes.” The time, Boesch said, is now. In terms of meeting the goals of past Bay agreements, he says, “We are now in the fourth quarter behind 48 [the amount of nutrient reduction vowed for 2010] to 18 [the amount achieved].” Howarth — a Cornell University scientist who drives a hybrid Toyota Prius and who buys only wind-generated electricity — worries that nitrogen spewing from vehicle exhausts and other human innovations is hitting Chesapeake Bay with a haymaker. We’ve known for more than a quarter-century that too much nitrogen for the Bay was like too much food in the belly. But Howarth’s research suggests we’ve sorely underestimated the damage of the nitrogen produced by agriculture, sewage, motor vehicles and fossil fuels. Standard wisdom has it that 20 to 25 percent of this nitrogen flows down rivers to coastal waters. Now Howarth finds that 35 to 40 percent of this pollution gets washed into watersheds in the northeastern United States. The wetter the climate, the worse the pollution. With ever-wetter climates predicted, combatting nitrogen pollution could be even harder than we expected. Once again, Howarth, says, what’s lacking is not the tools but using them. “We have regulatory authority to deal with it now,” he said. “But we need to do more to clamp down on vehicle emissions, and we may need to set more ambitious goals with climate working against us.” Bad news pretty much balanced good at the scientists’ gathering, until Palmer tipped the scale not with science but with heart: “What’s wonderful about Chesapeake Bay,” she said, “is that we care.”

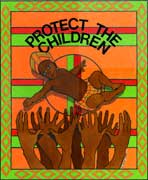

Pruning Season is Here February and March are great months for pruning summer-flowering shrubs and vines. Crape myrtle, flowering abelia, butterfly bush, clematis and summer flowering roses can be pruned now because they will produce their flowers on the new growth that will be initiated this coming spring as days grow longer and warmer. Don’t prune spring bloomers — including azaleas, rhododendrons, andromeda, mountain laurel, forsythia, weigelia, spiarea, viburnum, flowering crab apples, lilacs, cherry laurel — until after they have finished flowering. Since the flower buds of these species are currently formed and almost ready to open, pruning them now would reduce their flowering potential. But if you are growing apple, peach, nectarines, plum or pear trees for their fruit — as well as blueberries, raspberries or blackberries — now is the time to commence pruning. Pruning now and thinning later is the way to produce large attractive looking fruit. Good pruning tools are a must. Buy quality tools, and keep them sharp and clean. A fisherman’s sharpening stone or a pruner’s sharpening stone helps to keep the blades of hand pruners, loppers and long-reach pruners sharp. A spray can of WD-40 helps you keep the blades clean before and after pruning. The WD-40 is especially helpful when pruning pine, spruce, hemlock and juniper, which leave sap on the blades. Next week: Choose the right pruner for the job. Professor Emeritus Francis Gouin retired from the University of Maryland, where he was the state’s extension specialist in ornamental horticulture, to Upakrik Farm in Deale, where he practices the horticultural art and science he long taught. Follow his column of practical gardening and plant advice every week, only in Bay Weekly. Ask Dr. Gouin your questions at [email protected].  Artist On the Threshold Artist On the ThresholdDerrick Booth is custodian by day, image-maker by night by Carrie Steele Each week during Tuesday morning portrait-painting and Friday morning Art: Old Master’s Style classes, a figure regularly looks in over the shoulders of painting students. He pauses momentarily at the entrance of the studio before continuing on his way. Derrick Booth is on the clock, so he can’t stay. But his love of art lures him each week to the classroom at South County Senior Center in Edgewater, where he works. Learning the visitor was an artist, painting instructor Paula Fink asked him to bring in his works. What he showed Fink and her class surprised them. “Paula discovered that he was an artist,” said portrait student Nancy Bauer, who also noticed Booth’s interest in her painting class. “When he brought in his art, we were all so impressed.” Indeed, Booth’s drawings captivate the eye with their bold colors and often exotic themes. In one picture, a bright orange tiger peers off the page. In another, a happy woman in a lilac dress carries a basket on her head and a baby around her waist as she wades among tropical flowers. One of his posters portrays a baby lifted by dozens of hands under the banner Protect the Children. Bright, African-style borders frame many of his works. Meticulous lines and attention to detail give order to his prefered vibrant inks — magentas, lush greens and sunny yellows.  “Vivid colors have a feel-good nature that can change people’s moods,” Booth, 42, told Bay Weekly. “Vivid colors have a feel-good nature that can change people’s moods,” Booth, 42, told Bay Weekly.Pen and ink are Booth’s tools of choice, suited to the subjects he favors. “I like humorous drawings,” Booth said. “I draw everything from flowers to animals to people. And I include a lot of design and patterns: I love zebras because of their natural pattern.” Booth brings the exotic to the Chesapeake in his studio, a den he’s transformed into a creative space in his Annapolis apartment. He always draws facing a window. “I always have to have a window, where I can look out and meditate on what I’m going to do,” Booth said. What inspires him most is his imagination, he says. He also takes note of any and every work of art around him, he said, motioning to the art-decked walls of the South County Senior Center, where he is a custodian. In his crisp county uniform, this quiet artist keeps eyes and ears alert for inspiration while he works. A soft-spoken man, Booth — who was born in Baltimore and now lives in Annapolis — has been drawing since the sixth grade. A shy student, he used drawing as a way to think about where he wanted to go and what he wanted to do. Later, Booth went on to complete a two-year commercial art program in Baltimore. He hasn’t yet studied oil painting, so he’s learning, at a distance, along with the students he watches.  Now, all Booth’s art is done on his free time. Now, all Booth’s art is done on his free time.“I’m inspired by God’s creation, by something I see on the news that’s on people’s minds,” he said. “If I get inspired, then I’ll just put it on paper. I love to get the creative juices flowing.” Reserved by nature and calm in demeanor, Booth is an observer of the world around him. He takes notice. He seeks out beauty and messages to illustrate through his work. Though he’d like to have his art noticed, he’s not looking to be famous: He creates art for the pure enjoyment of creating. “I still enjoy it,” he said, “even if I don’t get paid for it.” He’d like to, however, turn his creations into T-shirts, posters and greeting cards — “something that gets people to think.” What gets him thinking are his other favorite pastimes: reading and visiting museums, as well as spending time with family, wife and children, brothers and sisters. As an artist, Booth’s thoughts come to life as images. So he’s happiest when his pictures and their messages “bring someone else pleasure and enjoyment.” To complete the circle of art and inspiration, artists must show their art. Derrick Booth just had his first show: One of his drawings hung alongside works of Edgewater senior center’s portrait-painting students. And he’s got plenty more vibrant drawings to show.

Seafood processors and other seasonal businesses could get help under her bill by M.L. Faunce Seafood processors and other specialty, seasonal Maryland businesses will get water wings to help them stay afloat this summer if Sen. Barbara Mikulski has her way. A feisty Baltimore native who knows her crab cakes, Mikulski explained to the U.S. Senate how family seafood businesses like the 100-year-old J.M. Clayton Company of Cambridge can’t find enough American workers to pick crabs and shuck oysters. So they rely on seasonal foreign help with special visas. The H-2B visa program lets employers hire temporary foreign workers when no American workers are available. But the program can bring in no more than 66,000 workers per fiscal year. This year’s quota was reached back in October. Because companies can’t apply for workers more than 120 days before they are needed, Maryland businesses weren’t able to apply for H-2B workers this year. “Many of our businesses use the program year after year. They hire all the American workers they can find, but they need additional help to meet seasonal demands. They desperately need seasonal workers before the summer so they can survive,” said Mikulski. The bill she introduced, a quick fix for this year and next, would exempt returning seasonal workers from the cap. “It does not get in the way of comprehensive immigration reform,” she said. Instead, she argued, it helps keep business and communities alive. “These are family businesses and small businesses in small communities in Maryland,” Mikulski said. “If the business suffers, the whole community suffers. These small businesses are a way of life.” More than seafood processors are in danger. “We have a lot of summer seasonal businesses in Maryland, on the Eastern Shore, in Ocean City or working the Chesapeake Bay,” Mikulski said. Paul Sarbanes, Mikulski’s senior colleague representing Maryland in the U.S. senate, co-sponsored the bill. “Our seafood processors are busy in the summer and early fall but have very little work in the winter,” he said. “They turn to temporary employees who are willing to leave their home countries for a few months to come to the U.S. and work.” As Sarbanes explained it, a falling seafood industry starts a chain reaction, upsetting a region’s whole economy. “Without this fix, our seafood processors cannot operate at full capacity,” he said. “That becomes a problem for the rest of the seafood industry, including our watermen, who will be forced to curtail their fishing because of an insufficient number of locations to process their catches. In the end, the people who suffer are not the seafood processors or the temporary workers but the watermen who cannot feed their families.” Virginia’s Sen. John Warner says businesses in his state face the same dilemma. “These H-2B workers are not taking jobs from Americans; they are filling in the gaps left vacant by Americans that don’t want them. The jobs we are talking about here are seasonal, labor intensive, and require a certain amount of skill, mainly in the areas of oyster and crab harvesting, seafood processing.” Seafood processing is labor-intensive work that resists automation. “Some in the seafood industry already tried to automate parts of crab harvesting,” Warner explained. “It was a complete failure. The machines failed to remove most of the bits of crab shells from the meat, and the consumers flat out rejected it.” Mikulski calls her bill the Save our Small and Seasonal Businesses Act. The crab-loving Democrat — whose website (mikulski.senate.gov/crabcake.html) features her recipe for crabcakes — might as well call it the Save Chesapeake Crab Cakes Act. In Washington, they’ll decide soon on Sen. Paul Sarbanes’ plan to establish a Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Watertrail. Sarbanes introduced legislation recently ordering the National Park Service to study the feasibility of a trail following Smith’s explorations along the Bay and its tributaries. There are 13 National Historic Trails now, including Lewis and Clark’s westward path and the Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights trail … |

||||||||

indefinitely his decision on planting Asian oyster in the Chesapeake, as the National Academy of Sciences suggests. Both testified in Senate committee last week, prompting DNR secretary Ron Franks to assert, somewhat bizarrely, that neither he nor the governor “will introduce any child-eating oysters into the Bay”…

indefinitely his decision on planting Asian oyster in the Chesapeake, as the National Academy of Sciences suggests. Both testified in Senate committee last week, prompting DNR secretary Ron Franks to assert, somewhat bizarrely, that neither he nor the governor “will introduce any child-eating oysters into the Bay”…