HIDDEN TREASURES

Appraiser Fair rewards amateur collectors

By Susan Nolan

Stuff. We all have it and unless you have given away all your possessions after a conversion to Marie Kondo’s cleaning style or have recently undergone your own version of Swedish Death Cleaning, you may be wondering what your stuff is worth. What’s the monetary value of that vase you received as a wedding gift? Is there a market for your grandmother’s silver? What about the antique toy truck you pulled out of your dad’s closet?

“We get inquiries all the time,” says Christina Barbour, St. Clement’s Island Museum site supervisor. “People bring all kinds of things to the museum and we just aren’t qualified to tell them the value. Even if we were, it would be a conflict of interest.”

Today, Saturday Jan. 22 is different. The small history museum located on Colton’s Point in rural St. Mary’s County is hosting its annual Appraiser Fair. Four expert appraisers are on-site and one is available via Zoom to consult with amateur collectors of every sort. The daylong event is in its 18th year and typically attracts visitors from all over southern Maryland.

I arrive with cash in hand—money to pay for the appraisal and money to be appraised. At the fair, the tickets are sold on a first come, first-serve basis for $5. I buy four tickets—two for currency and two for jewelry. The fee collected supports the museum through the Friends of St. Clement’s Island and Piney Point Museums.

There isn’t much of a wait and a volunteer quickly ushers me to the table occupied by Shari B. Mesh. Mesh is a graduate of the Gemological Institute of America and a certified gemologist and appraiser. She got her start working in her family’s pawnshop 30 years ago. Now, she works independently throughout Southern Maryland.

Today, she is seated in a small, warm, sunlit room. “I needed a space with windows for the light, but it’s good to have the warmth,” she says. She has been attending the Appraiser Fair since 2008. In front of her are the tools of her trade: a scale, a microscope, a laptop and a magnifying glass. I hand her a ring with carved snow-drop flowers on a large stone surrounded by pearls.

I’ve been curious about the ring’s value since purchasing it in an online auction in 2005. I paid $200 and was admonished by friends who thought I spent too much at the time. They said I would be an easy target for a scam-artist. I tell Mesh this and add, “I don’t regret buying it. I love that ring.” I know I will continue to wear it no matter what the value.

Mesh is also appraising an amethyst jewelry set—a necklace, earrings and a ring—given to me by my mother-in-law. She wore them to my niece’s wedding in 2010. I complimented her on them, and she gave them to me the following Christmas. I wear them on occasion, but admit that since COVID hit, I’ve had little reason to dress up.

As I talk about these items, Mesh is silently working to determine the value. She hands me a business card with notes scribbled along the edges. Every piece is valued much higher than I had imagined. I am giddy with excitement.

As for the amethyst set, “This is not a set at all,” Mesh says. “The necklace was originally a bracelet.” She shows me where it was altered to make it lay flat against the neck and how a rope chain was added to make it longer. She explains that the necklace and the ring are amethyst, but the earrings are a synthetic gemstone, but a good match.

“All our appraisers have donated their time today,” says Barbour. “Away from this event, appraisals can be expensive.” While many charge an hourly fee, Mesh charges by the piece. “Anywhere from $80 to $150 per piece, depending on how intricate it is and how much research is required,” she says. Appraisals performed at her usual rate yield page-long reports on each item, so that the client has an explanation as to how she arrived at the value.

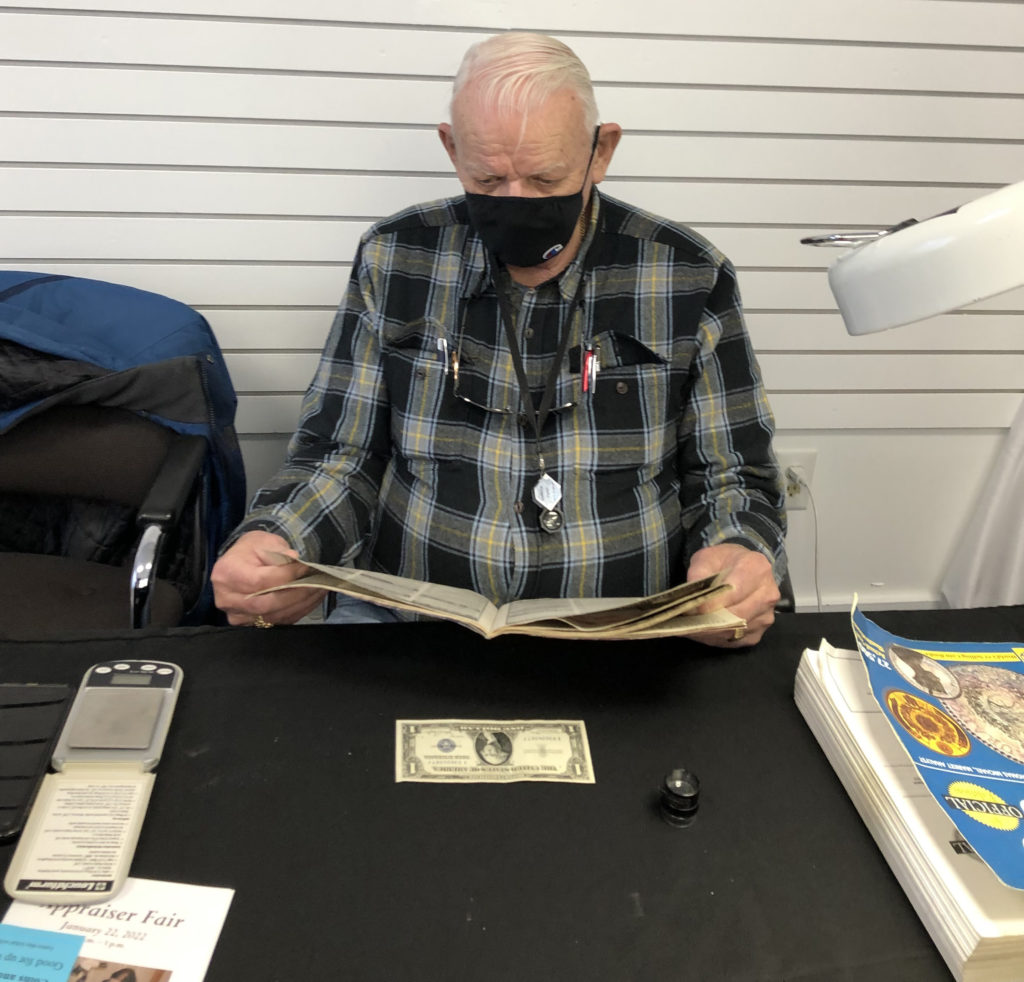

Next, I follow a volunteer through the museum’s galleries to William E. Parron of Parron Coin Co. Parron has been collecting coins for nearly 70 years and appraising them for almost 40. The Hollywood, Md., resident is a member of the International Numismatic Association and a certified life member of the American Numismatic Association (numismatics is the study of currency and coins). In addition to coins, he appraises medals, tokens, paper currency and clocks. He’s performed estate appraisals for Orphan’s Courts throughout the mid-Atlantic region.

I present him with my treasures: a 1935 silver-backed $1 bill and a 1963 $5 bill. I acquired both as change from cashiers, recognized they were old, and I’ve been keeping them in a desk drawer waiting for such an opportunity. To my eye, they are both in near-perfect condition.

“You see, here,” Parron says pointing to the words “Silver Certificate,” “The government no longer backs our money with silver. This bill has no real monetary value beyond being a collector’s item.”

Parron examines the bill closely. He describes it as “practically uncirculated with very little wear from handling.” He tells me a collector or dealer might pay as much as $15 for it. As for my 1963 $5 bill, Parron says, “It’s not in great condition. It’s in good condition. Maybe $8.”

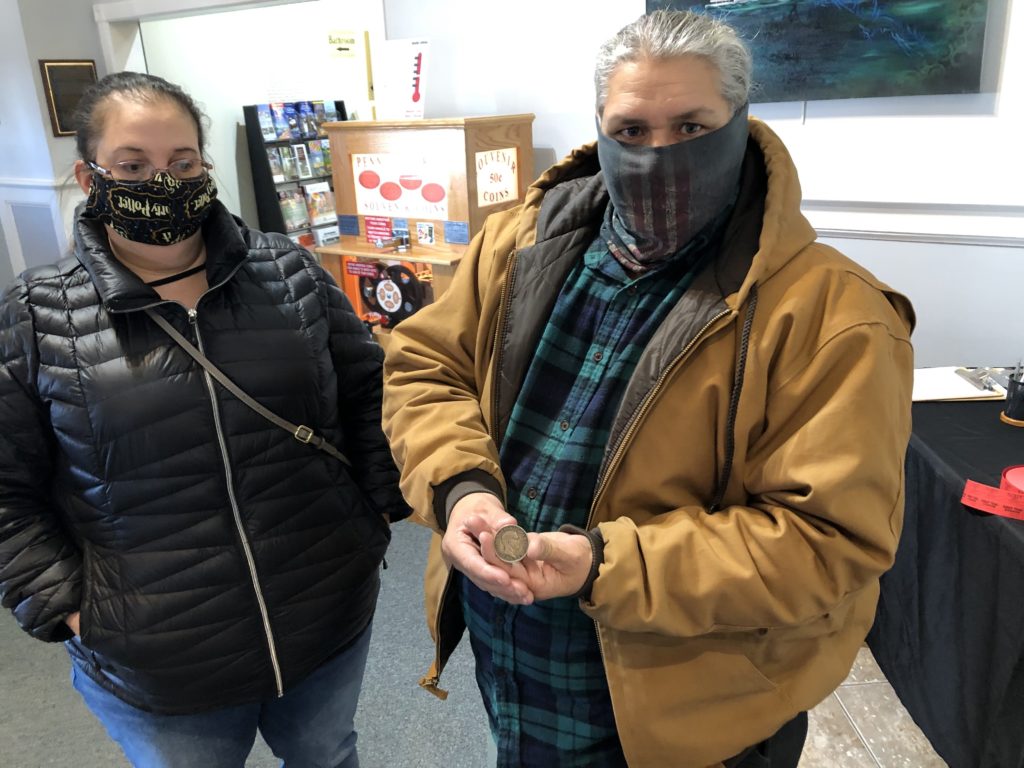

Parron’s next client is a more serious collector. Frank DiGeronimo of Lexington Park has always been interested in coins. He has brought a total of 16 coins with him, some foreign, and some are older US coins, all carefully placed in individual, hard plastic coin capsules for their preservation and protection.

“I started collecting coins as a kid,” DiGeronimo says. “I had a lot of relatives who fought in World Wars I and II. They brought coins back with them and because I was the person most interested, they found their way to me.”

Parron looks at each piece carefully, noting the date, the mint, the condition and the type of metal. Some of the pieces in the collection are only worth pennies, but others are valued at over $35.

DiGeronimo is pleased. “This was my first time talking with an appraiser,” he says. “I came in a little confused about what I had, but I learned a lot.”

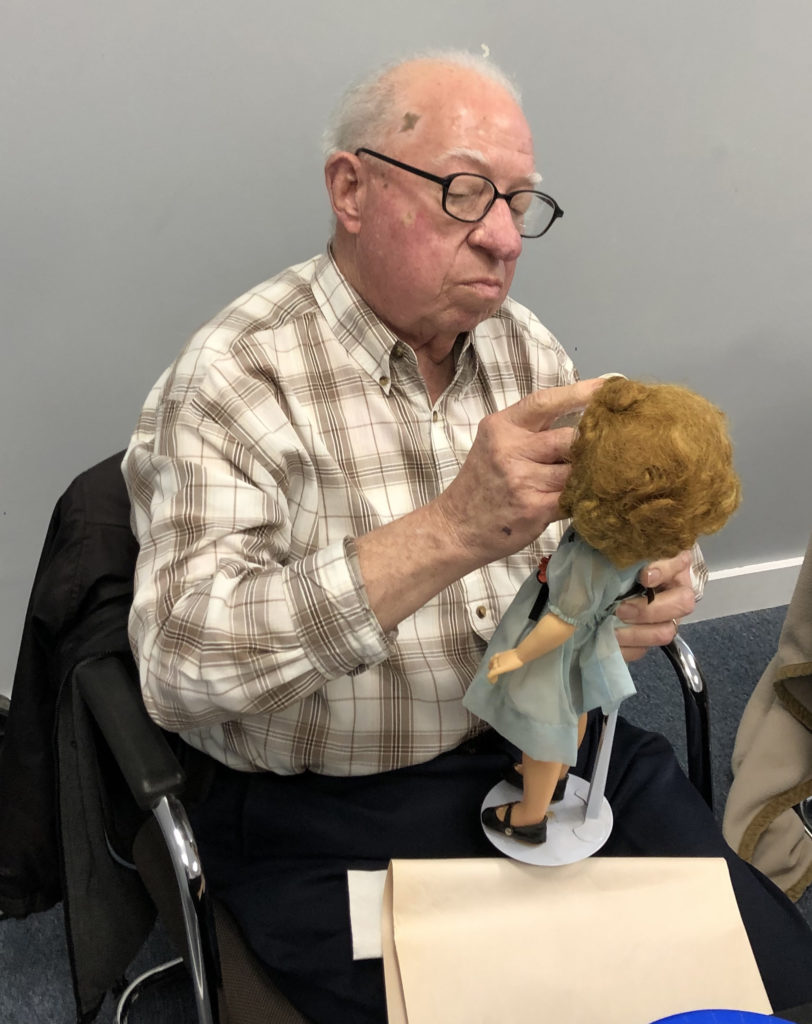

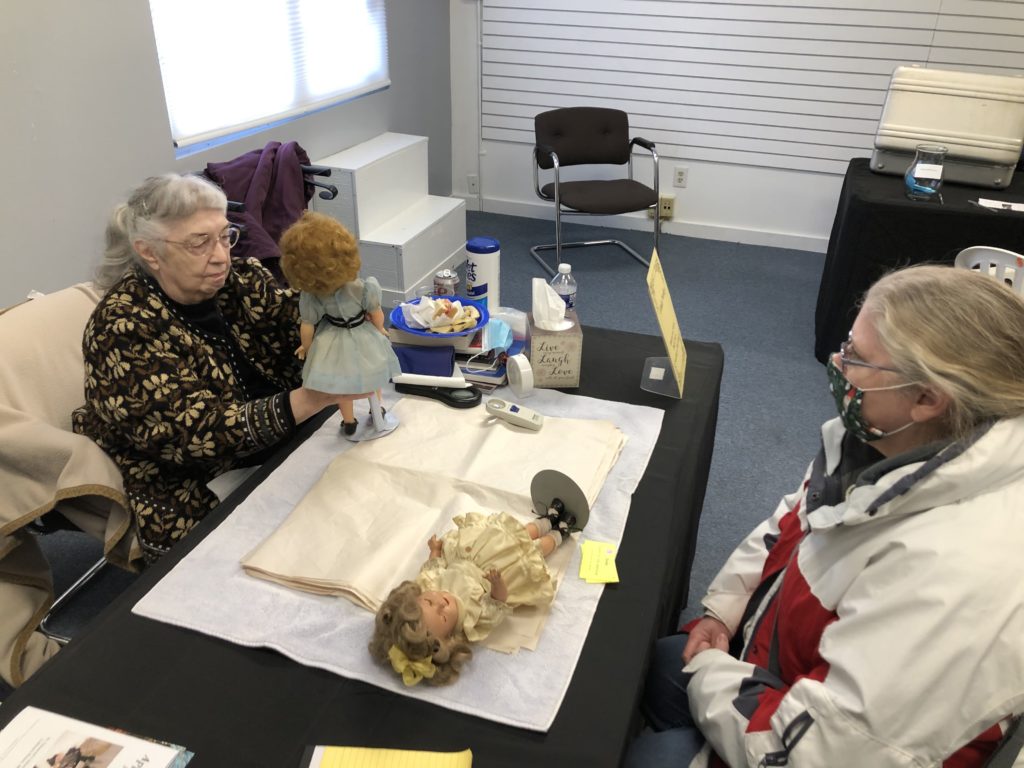

Linda Meidzinski of Avenue, Md., has a similar experience when she shows her Shirley Temple dolls to appraiser Linda Neeley of the Black-Eyed Susan Doll Club. Neeley is a lifelong collector and former owner of the Mary-Lind Doll Shop in Leonardtown.

“The value of collectible dolls has gone down in recent years,” explains Neeley. “People collect them because they love them, not because they are a good investment or high in monetary value.” She has seen people lose money on antique dolls. As a member of the United Federation of Doll Clubs, Neeley shares her expertise for free and has provided appraisals for insurance purposes.

Neeley dates the first Shirley Temple doll to 1957 and describes it as being in good condition. She tells Meidzinski she can clean the doll’s vinyl skin gently with a Wet-One. While the doll’s clothes and shoes are original, her socks are missing. The doll’s blue toile dress can be washed, but never ironed. Neely advises her to never use a brush or comb on the doll’s delicate hair but shows her how strands can be gently lifted and separated with a tiny, plastic hors d’oeuvres fork.

“She has flirty-eyes,” Neeley notes referring to a style of doll eyes that not only open and close but move from side to side, “but only one of those eyes is working.” She recommends Meidzinski use a touch of baby oil on a Q-tip to lubricate the broken eye for a quick fix. “Not too much,” she warns. “Baby oil can ruin the vinyl skin by making it shiny.”

Picking up the second doll, Neeley notes, “This one is much older. She’s from the 1930s and is a composition doll.” She points out the cracking on the doll’s hands, arms and legs. Composition is a mixture of sawdust and glue that was pressed into molds to make dolls in the first half of the 20th century. Because the composition cracks, collectors and dealers use wax to preserve antique dolls. Neeley believes this doll has been waxed.

“Her dress, shoes and panties are probably from the 1970s,” Neeley says, “And her wig has also been replaced.” Dolls from the 1930s have wigs made from mohair or occasionally human hair. Meidzinski’s doll’s wig is synthetic. Neeley values the 1957 Shirley Temple doll at $75 to $80; the older doll, because of its condition and lack of original elements, at only $50.

Meidzinski says she is not a collector. She saw the dolls at an estate sale and bought them because “they are cute.” “I wanted the 1957 doll, but they were sold as a set.”

Of the appraisal experience, Meidzinski says, “This is exciting.” She takes the dolls to her car and returns with more items to be appraised.

Chesapeake Ranch Estate resident Dorie Lear is a licensed fine arts appraiser and calls his company Gabby’s Antiques, after his cat. His usual fee is $100 per hour. Along with Henry Lane Hull of Wicomico Church, Va., who is consulting with participants via Zoom, Lear appraises artwork, pottery, silverware, glassware, music boxes, furniture, musical instruments, sports memorabilia, and a myriad of other collectibles.

“I can appraise just about anything,” Lear says, “and when I find I can’t give someone an answer, I refer them to someone who can. Other appraisers have specialties.”

A referral is what he gives Mechanicville resident Larry Hill, who arrived with a cardboard Amazon box. “I have my father’s violin in here. Maybe it’s worth something. Maybe it isn’t.”

Hill lost his father at the age of 6 and has few memories of him. “I know he played mandolin and ukulele, but I don’t remember him ever playing the violin, but this was his.”

“I can see the label inside. It says Stradivarius. Is it the real thing? I don’t know,” Hill says. Even if it turns out to be valuable, Hill doesn’t know if he would be willing to part with it.

It takes Lear very little time to decide the violin is likely a replica and in poor condition. Many of the parts have been replaced. Is it worth repairing? Lear refers Hill to someone who repairs string instruments in Calvert County.

Lear’s next customers are Phil and Kimberley Kenyon of California, Md. They are toting several paintings. Lear focuses on one painting in particular, a landscape. “It’s a watercolor, not chalk,” he says. “Chalk flakes and I don’t see any flaking.” He advises them to have it professionally cleaned to prevent it from deteriorating.

He values the painting at $150 and points out how unique it is. The boats in the foreground look Japanese, but the farmhouse in the background looks Norwegian. “This is a very nice painting. Beautiful.” Lear says.

I notice a trend among the appraisers. Even if an item isn’t the cash cow we have come to expect from watching programs like PBS’s Antiques Roadshow, all the experts are kind when rendering value. They recognize that an object is special simply because it belongs to someone who cares enough to bring it to the Appraiser Fair on this bitter cold day.

Dale Springer, president of the Friends of St. Clement’s Island and Piney Point Museums and longtime volunteer, says, “People generally leave here feeling good. Of course, everyone is hoping for big value.” He notes that the Appraiser Fair is not a high revenue event for the group, but he’s pleased with the turn-out.

I don’t see anyone leaving unhappy.

Learn more about St. Clement’s Island Museum, the annual Appraiser Fair and their other events at: stmarysmd.com/recreate/stclementsisland/