A Cross-Cultural Love

Couple challenged state laws, shared cultures with region

By Susan Nolan

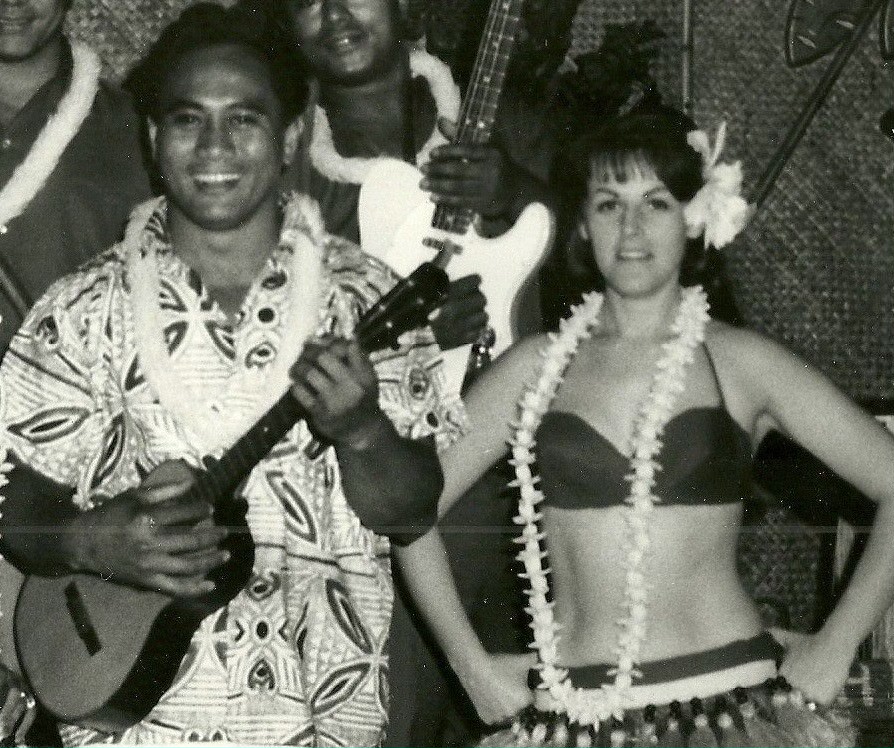

JoAnn To’alepai (nee Kovacs) has always loved Polynesian culture. “Even as a little girl I would listen to Hawaiian records and dance, so naturally, I took up hula,” says the Maryland native. It was while hula dancing at the famous Hawaiian Room at the Emerson Hotel in Baltimore, she met fun-loving Meki To’alepai, a musician and dancer.

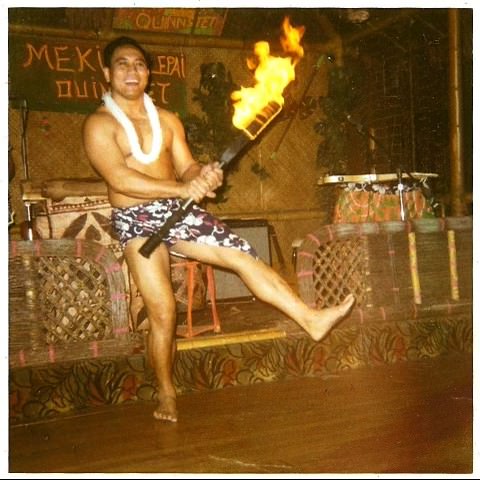

Meki had come to the United States from Western Samoa for the expressed purpose of sharing his culture with the American mainland. He began his entertainment career as a ukulele player, but before long, he was tossing flaming torches on stage as he performed the Samoan fire dance. He became smitten with JoAnn early on and referred to her as “the girl in the red hula skirt.”

“For him it was love at first sight,” JoAnn recalls. “I had just danced and gone back to my seat. He came right up to me even though I was sitting with another man, and he thought we were together.”

“I told that guy if he wanted to have a good time, he should dress like me,” says Meki. He was wearing a Polynesian dance costume, little more than a loincloth, at the time. As an entertainer at the Hawaiian Room, part of Meki’s job was to interact with the audience and make jokes.

That was in 1963. Meki and JoAnn have been laughing and dancing together ever since. They have performed all around the United States and made special television appearances on the Mike Douglas and Andy Williams Shows. They have met with American Samoan dignitaries—all in the interest of promoting Pacific Island arts and culture.

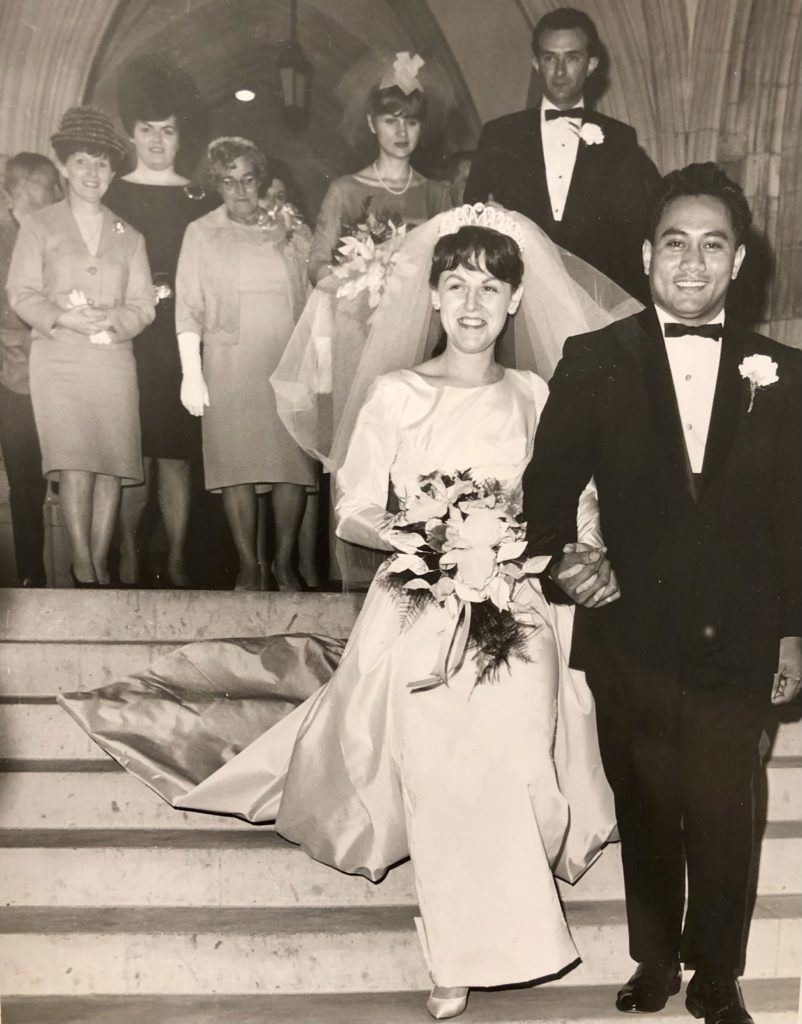

This is not to say it has always been easy. In 1966, the couple was denied a marriage license in Maryland. At the time, the Free State still adhered to a 1935 anti-miscegenation law that forbid marriage between whites and people of color.

According to JoAnn, they had arrived at the license bureau in Baltimore knowing what to expect. “Our minister had warned us we wouldn’t be able to get a marriage license in Maryland,” she says. “He (the Rev. Frederick James Hanna, an Episcopal priest) met us at the office with a photographer. He knew this would make the news.”

“So, we drove into D.C. and got a marriage license there,” Meki says.

The couple was married on February 19, 1966, in the Bethlehem Chapel at the Washington National Cathedral surrounded by family and friends. Their story made headline both locally and nationally, and they gained the support of influential law makers, including Hawaiian Senator Daniel K. Inouye and Maryland Delegate Verda Mae Freeman Welcome, the second African American woman to be elected to a state senate in the United States.

Political pressure and nationwide scrutiny brought about swift change. Maryland repelled the law within months of the To’alepais’ wedding. In June 1967, the US Supreme Court heard the landmark civil rights case Loving v. Virginia and ruled laws banning interracial marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The ruling nullified laws prohibiting interracial marriage throughout the country.

Back to Where it Began

The Hawaiian Room closed in 1970 and the Emerson Hotel was demolished in 1971 so wanting to share the culture they loved so much with the region inspired them to try something new. As newlyweds, the To’alepais lived in California for a while before returning to the Baltimore area where they founded Meki’s Tamure Polynesian Arts Group in 1969.

Polynesia is the Pacific Ocean region that includes Samoa, Hawaii, Tahiti, Fiji, New Zealand, and Tonga. Tamure is the Tahitian word for dance festival or party. The non-profit organization promotes a better understanding of Polynesia throughout the Chesapeake Bay area through educational programs, public speaking engagements, and performances.

Their sons Meki and Hini grew up performing alongside their parents. In 1993, son Meki and his wife Kim began running the organization’s day-to-day operations. They offer dance lessons and provide authentic Pacific Island entertainment at both private parties and public festivals.

“I’m proud of my parents and all they have accomplished,” says the younger Meki. That pride led him to nominate them for a Maryland Traditions Heritage Award from the Maryland State Arts Council.

Given annually since 2007, the Heritage Award recognizes long-term achievement in the traditional arts and is granted to people, places or traditions. As 2022 winners of the Heritage Award, Joann and Meki are recognized for “creating spaces in which Pacific Island people and others continue to learn about and participate in traditional Pacific Island music and dance.” This year’s other recipients are Baltimore-based gospel singer Shelley Ensor and the Waterfowl Festival of Talbot County.

Meki’s Tamure Polynesian Arts Group will be performing at the Chesapeake Children’s Museum in Annapolis on Sunday, March 27 for Maryland Day. Learn more: mekistamure.com.