Appreciation: One Man’s Legacy

Mayo resident John W. ‘Bud’ Taylor told us (https://tinyurl.com/BW-Taylor-99) that for him, being outdoors wasn’t exactly a drive. “It’s more a refreshment, like recharging your batteries,” he said. It turns out that it was actually Bud, who passed away at the age of 86 on Oct. 28, who was recharging our collective drive all these years to treasure and protect the Bay landscapes.

Bud interrupted our 1999 visit to his house on Pennington Pond in Mayo to perform a daily winter ritual, feeding cracked corn to annual visitors from Alaska: three dozen tundra swans. One expects those three-dozen are missing Bud this winter along with the rest of us. An award-winning painter, naturalist, photographer and author, Bud may have made a contribution still greater in how his art influenced and inspired those around him to work toward saving the Bay.

“He was a man with a conscience who was quick to discuss the importance of quality habitat, although not the type of person who would typically be seen at a hearing or other public forum,” says Dr. Matthew Perry, emeritus scientist at Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. “But certainly many were educated by Bud and carried his message to Annapolis and other political venues to help improve the quality of the Bay.”

Charging His Batteries

Bud started keeping a field journal of nature observations, particularly birds, when he was 15. His sketch-filled July 1947 compendium of that work is still posted online by the National Arboretum. There, from 1946 to 1950, he meticulously recorded the lack of black vultures and Canada geese (!) and D.C.’s last bald eagle nest — until 2015, at nearly the same Anacostia River hillside, Bud noted, when he returned there (like the eagles) after 65 years.

With his mother driving him over the top end of the Bay to reach the Eastern Shore — the Bay Bridge not yet built — he made bird habitat observations side-by-side with legendary Maryland birder Dr. Chandler Robbins (1918-2017). You can still see them in 1950 issues of Maryland Birdlife online. For six years, Bud was artist/editor of Maryland Conservationist, the predecessor to today’s Maryland Magazine.

In 1992 Bud told the Baltimore Sun, “Most people are surprised to hear that the marshes here have a great deal of appeal. I don’t know what it is — a combination of land and water, and what they mean. That’s why of all the birds I paint, I’m most excited by waterfowl. Working with them you have this marshscape — and the skies.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, his Patuxent River field journals from paddling trips with Patuxent naturalist Brooke Meanley (1915-2007) led to his paintings appearing in Meanley’s publications as well as Virginia Wildlife magazine and on Maryland’s first waterfowl stamp. By the 1990s, Bud’s own books appeared, Birds of the Chesapeake Bay and Chesapeake Spring, with his soft voice explaining nature’s intricacies amidst 100 of his paintings.

He told us in Bay Weekly (https://tinyurl.com/BW-Taylor-02), “I feel that I am only now attaining a mature understanding and appreciation of this one little corner of the planet.”

That corner was our region, with a particular focus on the Patuxent’s Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary in Bristol, where he was the 2002 Jug Bay Award recipient. Chris Swarth, theJug Bay director from 1989 to 2012, noted that Bud’s field journals and sketches “are a valuable record of Maryland’s changing landscape and dwindling bird populations.”

“I’m the world’s biggest trespasser,” Bud told Bay Weekly in 2002. “A no trespassing sign means good birding to me. Nowadays people chase you off, but it used to be that the landowners were as interested as you in what you might find.” At Jug Bay during private ownership in the 1970s, Bud was “nearly chased off” by the owner, but pulled one of his paintings from his car as a gift, and “their relationship improved considerably.”

How Many Acres Can One Man Save?

Bud’s impact on land conservation was monumental.

“I think there is a direct link between what Bud did in his art and influencing the increasing regard for the natural values of the river, the wetlands and the Bay,” says former Patuxent River Park director Rich Dolesh, now vice president of the National Recreation and Park Association. “It was very much because of artists like Bud who were interpreting the incredible natural value of wetlands that planners and elected officials began to change their minds in general, and about the official plans for Patuxent River Park in particular.”

Note this as a reminder of how things have changed during Bud’s 65 years of impacting environmental thought: In the 1970s, Patuxent River Park master plan included a full-service marina, an airstrip for private planes and an 18-hole executive golf course next to the wetlands and river.

Preserving more land and wetlands along the Patuxent was not on the program at Bud’s beloved Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary. In 1988, Anne Arundel Recreation and Parks Director Joe McCann turned down an offer on what (13 years later) would become the Sanctuary’s Glendening Nature Preserve. McCann explained his position in a November 1988 memo to then-Sanctuary director Christine Gault — uncovered by a freedom of information request filed by The Capital. “Your personal views might interfere with [our] policy [and you are directed] not to give any professional opinions on the project to any elected official.”

“I don’t see me recommending any more acquisitions in the Patuxent River watershed near Jug Bay to [County Executive] Lighthizer for a while,” McCann said.

Bud responded in his typical understated yet effective manner.

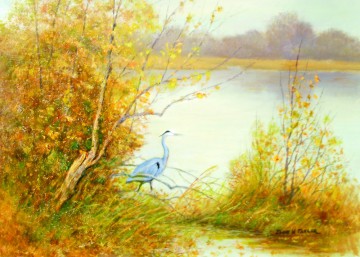

He appeared with Lighthizer, McCann, Gault and Friends of Jug Bay president Marjorie Crain at a ceremony overlooking the Patuxent at Jug Bay to donate a portrait of what became perhaps his best-known subject, a great blue heron. This donation included full copyright, with his directive that all proceeds from the thousands of poster-sized prints (and from an osprey painting that he later donated) be used for conservation of land and marsh and habitat improvements at Jug Bay.

“I wonder how much people are affected by art?” Bud once mused in my hearing. “Can my work really help the cause of conservation?”

We have the answer.

On the front lines of observing and recording nature for 65 years, becoming adept at influencing public awareness and sentiment on Bay preservation, Bud told Bay Weekly in 1999, “Those politicians who say they’re bringing back the Bay … They don’t know what the Bay was.”

That awareness and an artist’s ability to illustrate that message for thousands of Bay area citizens (and the occasional politician) will be missed. Though perhaps not missed as much as by a particular flock of three-dozen tundra swans on Pennington Pond this winter.