Back to School?

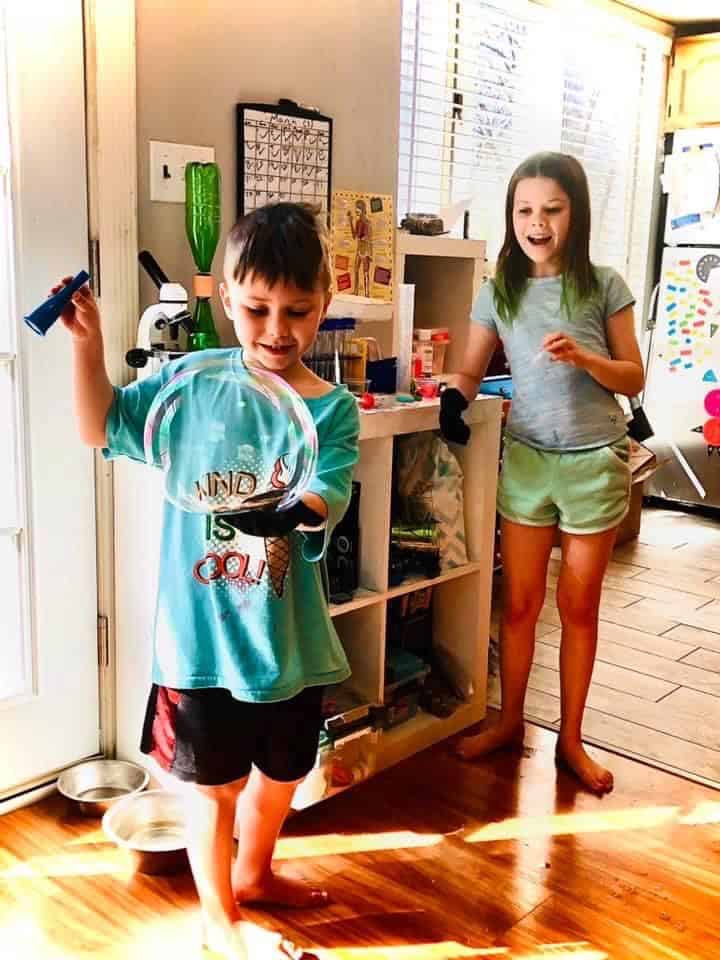

Courtesy Jillian Amodio.

Courtesy Jillian Amodio.

Courtesy Jillian Amodio.

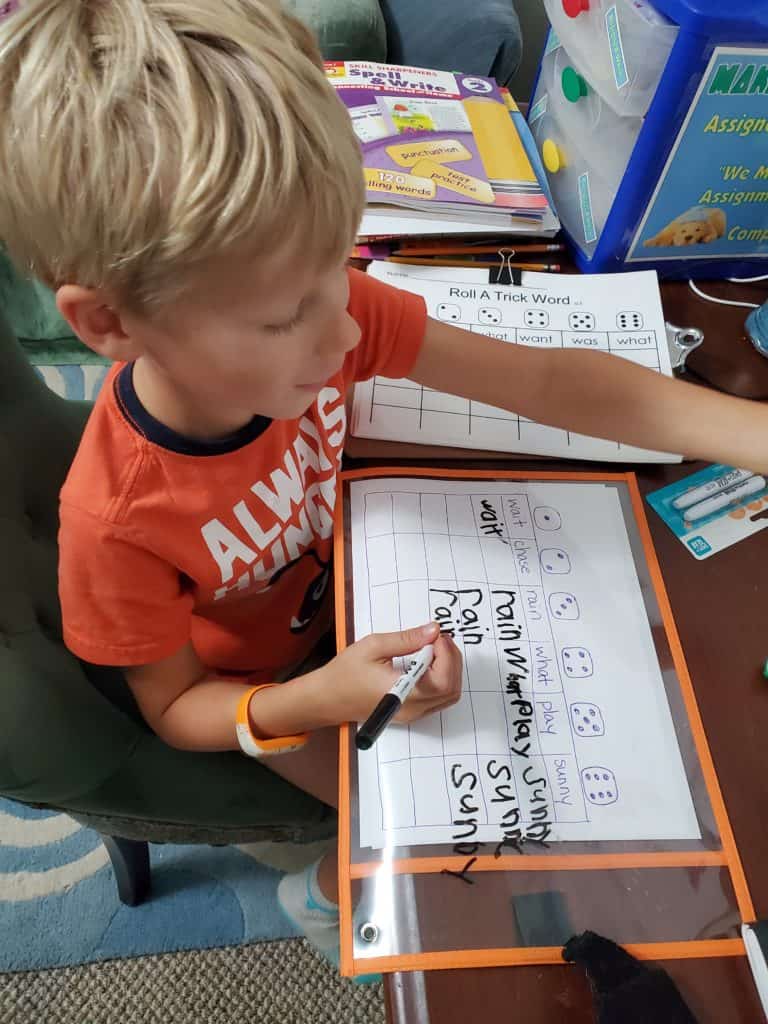

Courtesy Megan Perry.

For some families, school is not the place to be

By Kathy Knotts

After over a year of virtual learning, public schools are opening their doors to students for in-person classes this year. Students in Calvert County began their school year Aug. 31 and Anne Arundel County students will begin Sept. 8.

With heated school board meetings, community protests, debates on social media and a nationwide shortage of Lunchables, this school year is already off to a rocky start. How to approach education and learning safely and robustly has become possibly one of the biggest issues to arise out of the pandemic.

But for some families, “back to school” holds little significance as their classroom is as far as the kitchen table or logging into an online school. CBM Bay Weekly talked to a few families about how they are approaching this school year as former or current homeschoolers.

Back to (Public) School

In 2020, there were nearly 79,000 students enrolled in Anne Arundel County schools, a decrease from previous years that is likely due to the pandemic. Calvert County’s enrollment numbers have dipped slightly as well compared to pre-pandemic figures; this year’s student enrollment is 15,527 compared to the 2019-2020 school year which saw 16,022 students enrolled.

Yet, a return to in-person learning and open buildings is welcomed relief for many families, like Jillian Amodio’s. After homeschooling for several years, Amodio will be sending 10-year-old Juliette and 6-year-old Jake to public schools next week.

“I am still very conflicted on my choice but so much has been stolen from our children and as much as I fear for their physical well-being and health, I am also concerned with their social-emotional, and mental health needs” says Amodio, an occasional Bay Weekly contributor. “School is an environment (albeit an imperfect one) where children experience the nuances of peer-to-peer relationships, learn conflict resolution, and begin to understand different perspectives, belief systems, interests, family dynamics, and cultural tendencies of peers.”

Amodio’s family began homeschooling when Juliette was in second grade and she attended in-person school for third grade. But when the COVID pandemic began and Juliette had to switch to virtual learning in fourth grade, it became clear to the family that homeschool was the better option. “She was failing her classes because sometimes the Zoom links were not working, sometimes the sound was not working, and sometimes assignments were not updated correctly. It became a very dysfunctional environment despite best efforts. School and learning became a source of anxiety and anger rather than a source of excitement and eagerness to discover more about the world around her.”

Local parent Sandy, who wished to be referred to by first name only, said that sending their teenage children back to in-person learning didn’t come without thoughtful consideration. “They had a year of dealing with circumstances none of us have ever had to do. Many failed educationally, but successfully learned to cope, handle social media, technology and more.”

Sandy says COVID is still a very real concern. “Yes, I worry about COVID and those who are not vaccinated. Mine are, but I worry that it will be a never-ending battle.”

Parents also expressed apprehension that in-person learning could begin to look like hybrid learning did last spring, with children sitting in a classroom on a Chromebook. “The risk isn’t worth it for them to be there if they aren’t getting the full attention and teaching that they need to succeed,” says Sandy.

Last year’s hybrid model helped seal the decision for Tracy Sweeney-Hazelton’s family. Her 10-year-old son was at Crofton Elementary when the pandemic sent him home. “Virtual learning was such a waste,” says Sweeney-Hazelton. “I had to be in control of everything all the time and there was so much work. It was ridiculous.”

Sweeney-Hazelton could see her son was getting frustrated. “We talked about it a lot and my husband and I asked him if he wanted to continue with virtual learning. And he just asked, ‘Why can’t you teach me?’”

Homeschool is Trending

According to the Maryland Homeschool Association, Maryland saw an unprecedented increase in the number of families who filed the Notice of Intent form to homeschool during the first quarter of the 2020-21 academic year. Between June and November 2020, more than 13,000 children transitioned from pandemic school-at-home to official homeschooling.

While the total number of Maryland homeschool children now exceeds 40,000, increase in numbers were not uniform across the state, states MDHA. Baltimore City saw the smallest change, with less than a 15 percent increase in numbers. Garrett and Harford counties, on the other hand, experienced triple-digit jumps in the total number of homeschoolers. Somerset County was the only school district to experience a small loss in homeschoolers.

In Anne Arundel County, the number of homeschoolers went from 2,825 in 2019 to 4,891 in 2020. Calvert County went from 725 students to 1,391.

“I never saw myself as a mom that would homeschool,” says Sweeney-Hazelton. But her son’s struggles with the online model forced the change. “It became apparent within the first month … he didn’t like being on camera and being online that much. It actually upset him to see all the friends he couldn’t physically be with anymore … He stayed with the class till the end of December and I submitted my withdrawal papers and we started homeschooling Jan. 3.”

Cristin Orr Shiffer said she never saw herself as a homeschool parent either. “I have never identified as a homeschooler, it was not something I ever even considered, even being from a military family and knowing a lot of families who have done it.”

But Shiffer says the pandemic has changed all that. “I looked at all the pros and cons for us, we have a first-grade son and a high schooler. The 10th grader is vaccinated so we are sending her back to school. But for our first grader it didn’t make sense for us [to send him back]. He’s in a good place academically and not suffering emotionally from not being in class. So he will be staying home instead.”

During their year of pandemic homeschooling, the Amodio family embraced the aspects of an education outside the classroom, especially for her young son Jake. “I knew for this age that online learning was not feasible or appropriate for his high-energy personality. He is an active kid who I could not expect to sit in front of a screen for hours on end. Both of my children enjoyed the flexible nature of homeschool, enjoyed interest-led learning, and delighted in the various field trip opportunities and hands-on learning experiences I was able to provide. In a time where there was so much we ‘couldn’t do’ because of the pandemic, we created a world where they had copious amounts of free time, choices, and opportunity to just be kids while still ensuring that their basic education needs were being met.”

Life outside the classroom also means taking control of the curriculum and lessons, an important point for Sweeney-Hazelton. “Honestly, it’s not about the virus for me, I have an issue with what the schools are teaching. I found some things out since withdrawing him that are being taught that I’m not for. I think parents need to be involved and take control of their kid’s education… I don’t want to worry what he is being taught or how he is being treated.”

Academics are the least of Amodio’s worries for her children. “Currently, I have no concern about academics. Children by nature are natural learners. They will learn despite any best efforts to hinder their consumption of knowledge. This year my main concern is their emotional and social development… Learning will occur, my main concern is preserving their emotional well-being.”

Megan Perry worries that some families are not well-equipped enough to be pulling their children out of school to learn at home. Perry, a teacher for 17 years in Calvert County, says the pandemic has shown her that some caregivers don’t realize the level of participation required in taking over their child’s education.

“I do worry about the skill set that most parents have, if they are going to homeschool for the first time,” says Perry, who has elementary-aged children herself. “Teaching is definitely an art and it’s not necessarily as easy as people think it is.”

Perry left her teaching job last year during the pandemic and has decided to continue teaching her own children at home. But it’s a very different situation from teaching students in a classroom. “We’ve always encouraged our children to [learn] by doing stuff and I love the flexibility homeschooling gives us. If my son, who has a head for numbers, wants to do two hours of advanced math, we can do that. If my daughter wants to create art, we can do that, too. It’s a different structure, but I am still very rigorous about academic standards.”

Whether their children are returning to traditional school or not, these parents are watching COVID trends carefully.

“I am absolutely concerned… my children are still too young to be vaccinated,” says Amodio.

Shiffer wishes that a bridge system had been explored to allow the youngest students to continue virtual learning until they could be vaccinated and return to in-person classes. “I had high hopes, as I think everyone did, that school was going to be OK—the delta variant was not a household name in May and that’s when CCPS set the deadline to apply for the virtual option.”

“I don’t know when or if we will return to public schools,” says Perry. “It’s such a changing dynamic with the virus. If everyone was vaccinated and numbers were low, then chances are I would feel more comfortable about sending them back. But as a former teacher, I know that people will send sick kids to school anyway.”

Online Options: There is a third option between traditional school and homeschool. Both Anne Arundel and Calvert counties invited students to enroll in a virtual academy. Families had to make the decision by the end of the last school year and the option was only available for grades 3 through 12. In Calvert, 236 students will attend the virtual academy. In Anne Arundel, 520 students applied and were accepted to the virtual academy. Each county has its own administration for the online schools.