Citizens of the World

Walking through Gaziantep, Turkey, meant keeping an eye on any young man walking toward me. At the instant he was about to bump me, I did a quick sidestep. In that conservative eastern country 45 years ago, this was nothing to worry about: just a young man’s trick. My sidestep was one small adjustment Peace Corps volunteers make to live by the rules of a foreign culture.

I’m one of 200,000 Americans who has volunteered in 139 countries since the Peace Corps’ founding on March 1 a half-century ago.

A surprising number of us are your neighbors. We tend not to brag about our service, but our stories, ringing of adventure, hint of life-changing experiences.

In the beginning most were kids, right out of college, liberal arts generalists sent to teach English or develop third world communities. Peace Corps became wiser and now sends volunteers of all ages, especially people with skills and experience, such as business, farming, tourism and mechanics. Over the years, the average join-up age has risen to 28.

Marking the Peace Corps’ half-century anniversary, here are six stories from our own returned volunteers, which they will tell at the Calvert Library in Prince Frederick on March 5.

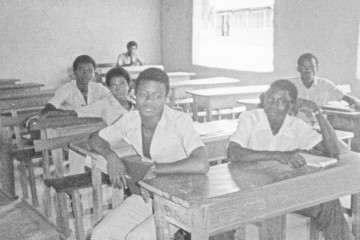

Sandra Lauffer teaching English to as many as 40 high school students at a time during her Peace Corps stint in the African nation of Malawi. |

Sandra Lauffer, Malawi, 1966-’67

“I went because it was the early heady days,” says Sandra Lauffer of Prince Frederick. “JFK had been assassinated, and Peace Corps was in the air. I was just graduating from college, and it was very compelling.”

The nation of Malawi had asked the Peace Corps to provide teachers so all students could attend secondary school, not just those who could afford private boarding schools. Thus Lauffer, who had never heard of this underdeveloped Central African country, spent 1966 and ’67 teaching English to high school students, 40 to a class, and learning about their culture.

“The Malawians are a very warm, embracing people, and I saw the effect of that warmth on people as they struggled with poverty.

“The students worked very hard. They saw that that was the way to get ahead,” Lauffer remembers. “Because kids had to pay school fees, they often had help from relatives, and there was an enormous responsibility to do well.”

Few girls were in her classroom. “Out of 40 students, six would be girls,” she recalls. “Girls weren’t expected to go to school, and if they had a few years’ education, they were choice marriage candidates. You wouldn’t see them after a couple of years of high school, as teachers or headmasters married them. Educated men wanted a wife with some education.”

Forty-five years later, Lauffer calls those years “a life-changing experience.”

“It led me into an international focus that gave a new direction to my life: helping people learn about other people, other cultures.”

Beverly Izzi, Bénin, 1983-’85

Beverly Izzi, top, taught high school cell biology and geology in a small village of poor subsistent farmers during her two years in the Peace Corps.

|

Twenty years later, Beverly Izzi went to a west coast African nation, Bénin, a key-shaped country with its narrow end on the Atlantic Ocean.

She taught high school cell biology and geology in a small provincial capital, Djoubou. The richer people had mopeds; very few had cars. Her neighbors had many wives, and her alarm clock was the Muslim call to prayer.

“I lived in a small village of subsistent farmers. They were very poor, poverty I’ve never seen before. Our diet was mostly tomatoes, onions, garlic and baobab leaves. There was no running water or electricity. But it was a village that was very happy,” she recalls.

“Often the students lived outside town, so they had to work in town to live and pay for school and uniforms. Because their family was sacrificing and losing a pair of hands to work the farm, the kids had worked hard to get there and were so happy to be in school.”

Her classes, too, were mostly boys. “It was like an earlier time in our history when you invested more in your sons than your daughters.”

Toward the end of her stay, Izzi worked with women’s groups in the village. “They work very hard, farming all day and then at night with me raising rabbits,” she says. “We also had a pig project. I wrote a grant for $1,500, and we fenced them in. In Africa they let animals graze anywhere.”

Izzi is now a children’s librarian at Calvert Library in Prince Frederick. “I went because I wanted to help other people,” she explains. “The Peace Corps changed me, but it wasn’t tangible. Afterward, it was important to have a job that was meaningful and morally correct.”

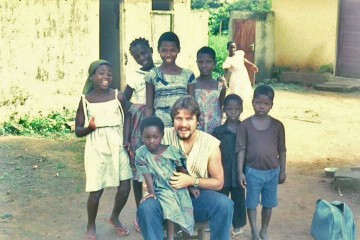

Mark Gorsak, Togo, 1986-’87

Mark Gorsak lived in the heart of voodoo country in Togo, where he taught statistics and algebra. |

In Togo, just west of Bénin, Mark Gorsak lived in Tabligbo in the heart of African voodoo country. He took a lot of pictures, but, as he explains, “With voodoo, there was the belief that you were stealing their soul, so I had be very discreet. One time in a market I took a picture of a voodoo stand. Fortunately, I was on a bicycle.”

Gorsak taught statistics and algebra to high schoolers in French, the official language of this impoverished agrarian nation.

“I was teaching sampling and asked the class How much corn is out there? The class had wild answers and no idea there was a way to find out. I taught them how to sample and estimate. I am now a survey methodologist.”

On the side, Gorsak took on an environmental and subsistence project.

The forest was being cut down for firewood. “To reduce the demand for wood,” he says, “we built clay ovens for a more efficient use of charcoal.”

Gorsak’s years in the Peace Corps changed his style.

“Before I went,” the Lusby resident says, “I was very competitive. When I came back, I was slow and methodical, and have been ever since. You learn to sit down, have a beer and enjoy today because tomorrow you might not be here. Even now, it’s kind of what I live by. Life is what’s important. Enjoy it.”

Ray Sabella, Honduras, 1990-’92

Ray Sabella, center, not only served in the Peace Corps in Honduras: He met lifelong friends there, including his wife. |

Half a world away in Central America, Ray Sabella learned the same lesson. The 32-year-old forestry graduate lived in Ocotepeque, a provincial capital of Honduras, working in wildlands management at the newly created Cloud Forest National Park, 5,900-plus feet above sea level.

He joined the Peace Corps “for altruism, to help people out,” he says. He could help, he learned, by not being the expert. Speaking little Spanish helped him learn that role.

“You think you know more than they do, and they may not be doing it right, but they are doing it wrong for a reason,” the cartographer says.

“We built beehives, for example, and they learned the relationship to the habitat. This was to get them away from burning the forest,” he says.

His second job was working “with local officials who had no experience to set up a management plan, determine boundaries and conduct a biological inventory.

“I created my own measures of success,” Sabella says. “Think small. Open the eyes of one kid to the worth of the park. Did my presence make a difference to this or that person? Not, did I build a school or something.”

Ocotepeque is still part of his life. “My wife is from Ocotepeque,” says Sabella, who now lives in Lusby. “That’s where my friends are. Those are all lasting relationships.”

Kelly Langford, Panama, 2007

While a Peace Corps volunteer in Panama, Kelly Langford worked to create jobs for the poor. |

Kelly Langford of Hollywood in St. Mary’s County was a 25-year-old working professional when the Peace Corps sent her to create jobs for fair pay in a little Panamanian village. Despite her skills, she faced challenges in that poor country.

“There’s a very high divide between the rich and the poor, and with no middle class it spreads corruption. Panama has a resource in the Panama Canal, which brings in millions, but the money doesn’t get to community development or infrastructure,” she explains.

“I supported a women’s bakery started in the 1970s, trying to keep it afloat. There was a lot of opportunity, but it was hindered by a lack of education and professionalism. They don’t know how to go to a bank or use calculators.”

Langford learned that “in development work, making change was in the little things. My feeling was that if something created jobs, it was a success.” By that measure the bakery, La Cooperative Fe y Esperanza — Faith and Hope Cooperative — successfully maintained jobs for impoverished women and was stronger when Kelly came back to the U.S.

Jennifer McFann, Georgia, 2006-’08

Jennifer McFann, here at right with her host family, taught English while in Georgia for the Peace Corps. |

Jennifer McFann found herself at a crossroads of history.

“It was neat to be part of a post-Soviet nation for its first two years separated from Russia,” reports the international relations major of her two years teaching English to fifth- through 11th-grade students. That was her morning job. Afternoons, she designed a computer course, worked with a women’s group, provided environmental education and created an English classroom.

“I assisted the community as ambassador for the U.S. for two years,” McFann says. “It was fascinating for people to meet an American and see what they are really like.”

Just as fascinating was learning what her host country was like.

“I didn’t know anything,” she says. “I thought it would be like Russia. It was completely different.”

From her years in Georgia, the current Peace Corps recruiter says she “gained an appreciation for time and learned that a career is not the be-all and end-all to everything. “I acquired an increased level of confidence and learned to interact with other cultures.”

* * * *

“We’ve been and seen things others haven’t,” Kelly Langford says for all us generations of Peace Corps volunteers. “We’ve immersed ourselves in different cultures, different socio-economic levels.

We’re lifelong citizens of the world.”