Colonial Maryland’s Complicated History

Historic London Town Celebrates 50th

By Jillian Amodio

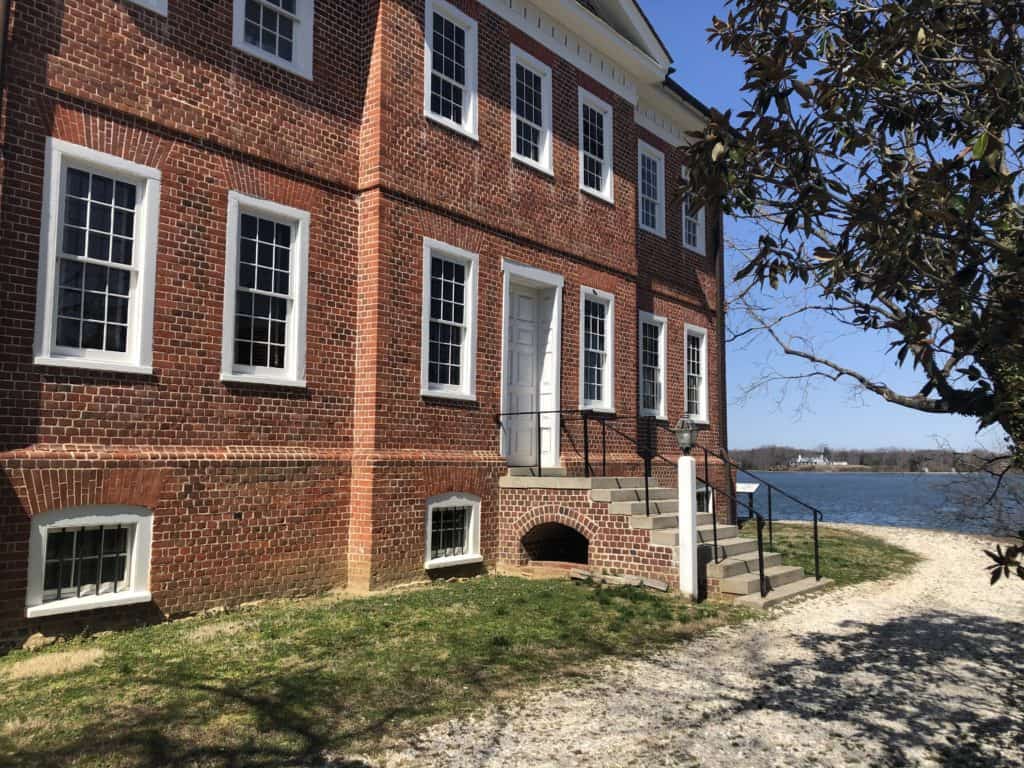

Decades before the birth of our busy capital city of Annapolis, there was another center of trade and travel along the Chesapeake Bay. Today we know it as Historic London Town and Gardens in Edgewater, celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, but back in 1683, when it was established, it was an important port and center of commerce for the earliest settlers.

Trade routes were an integral aspect of colonial success: A nation’s power came from its trade activity, exporting more goods than they imported as a means of gaining economic advantages. While tobacco may have been London Town’s main export, a much darker trade occurred in the South River harbor as well. Slave ships arrived on the shores of the colonial town, where they would unload their “cargo” and sell to the highest bidder.

One such slaveowner and London Town resident was William Brown. Sometime between 1758 and 1764, Brown built an extensive Georgian style brick home overlooking the South River. While he spared no expense on the exterior of the home, the inside bore more humble furnishings and Brown never actually saw the interior to completion. The brick mansion was a stark contrast to the rest of the town which consisted mainly of small wooden structures serving the various needs of the day.

For a while the house served many purposes. It was a tavern and inn, a place of work for his slaves and indentured servants, and a home to his family, including his wife and children.

But almost as quickly as London Town rose to prominence, it began to decline, failing to thrive against larger ports like Annapolis and Baltimore. The trade slowed, business waned, and Brown succumbed to bankruptcy. In an attempt to alleviate some of his debt, Brown sold his furniture, his home, and his slaves: Sall, Harry, Osborne, and Jacob.

According to Lauren Silberman, Deputy Director of Historic London Town, Brown ended up dying alone and debt-ridden, living with his son-in-law in Annapolis.

After declaring bankruptcy, Brown’s home became a rental property and then an almshouse during the 1820s. Almshouses were a form of “charitable housing” provided to people in need, however, like many in their day, this one was described as being an abode of misery where inhabitants endured cramped and unsanitary conditions.

While enslaved people were not permitted to live in the almshouse, there were several free African Americans living in the deplorable conditions. Those permitted housing were often mentally ill or unable to work. They resided in a dormitory called the “negro quarters” which the Maryland Board of Health found to be even worse than the areas occupied by the white residents. The almshouse closed in 1965 and the 14 individuals living there relocated.

With the closure of the almshouse, Anne Arundel County turned the land into a park. Horticulturists and volunteers worked diligently to improve the soil composition in order to support the gardens that we enjoy today. The gardens were created completely separate of the area’s colonial history and bear no historical accuracy to what the land would have looked like in the past. Even so, the current staff works tirelessly to preserve the horticulture alongside the history.

Caring for the 23-acre park, which combines history, archaeology, and horticulture, is no easy task. The land itself is owned by the county, but the London Town Foundation, a non-profit organization created in 1993, manages its care, with the goal to inspire a “deeper understanding of our region’s history, environment, culture, and arts through living history, historical artifacts, experiential public gardens, and collaborative cultural & arts programs.” Silberman says the staff tries to go beyond mere factual history and humanize the experience of Colonial life. A new round of grants will help with interpretive signage that will include biographies of some of the different people who lived there including slaves and indentured servants.

Despite hitting some hardships during COVID, Silberman says the site is grateful for the support of donors. “This past year was one of the hardest years we’ve ever faced funding-wise. We had great success with our ReLeaf fund. We raised over $50,000 from private donors.” She also mentioned that, with the help of grants, they were able to maintain much of their existing staff throughout the pandemic.

Immersive experiences are made possible by the dedicated staff including Director of Horticulture Meenal Harankhedkar, Landscape Manager Dylan Bacon, and other staff as well as a dedicated group of volunteers. Every Tuesday, regardless of the weather, volunteers descend upon the grounds to help care for the massive horticulture display. Silberman says that while the two full-time and two part-time employees are the largest horticulture staff they have ever had, it is still a small fleet to tend to such a large area which is why they are grateful for volunteers.

Pat Morrison, a long-time volunteer did not grow up in Maryland. When she moved here, she saw an ad in the paper that London Town was looking for volunteers and she figured it would be a great place to learn all she needed to know about gardening in a climate that was new to her.

Stephanie Jacobs, a William Brown House docent, got involved after her interest was piqued while attending a lecture series on site. She loves sharing the history with visitors, “The tavern life was so interesting and it’s fun to share the stories.”

Stories of history and mystery are endless at London Town. In 2002, archaeologists discovered a burial shaft, housing the remains of a 6-year-old child beneath the old carpenter shop. It was concluded that the child buried beneath the floorboards was a slave and his lineage was traced back to Gambia where it was customary for the body of a deceased loved one to be buried beneath the family’s living quarters. It was not a cultural practice for family to leave any sort of permanent graver marker. To honor him, the body was ceremoniously reburied where it was found without a grave marker.

Other archaeological finds from the site feature items that tell a dual story. For instance, an expensive wine glass tells not only of the wealthy individual who may have drank from it, but also of the slaves who would have been made to fill it. A “chicken burial” was unearthed in 2004 during an archaeological dig. Workers found several chicken skeletons, neatly arranged, indicative of burial practices or a sacrificial offering to mark a birth or death that would have been customary by some of the enslaved population. Some history is fascinating, some is enlightening, and some of it is sinister. Yet all of the history is worth learning about.

Today visitors can tour the historic structures, stroll through the scenic gardens, and enjoy educational activities, lectures, and events for all ages. While the William Brown House remains closed to the public, there are plans to reopen in the future.

“Our goal has always been to be a place of hands-on historical discovery,” says executive director Rod Cofield, who is eager to allow for more opportunities when work on the house is finished.

Historic London Town opened its gates for Maryland Day and will mark its anniversary with a lecture series beginning April 6. Cofield will share stories of the site through the past, present, and future. “I have great admiration for the visionaries who undertook the tremendous effort of transforming London Town into a park and museum 50 years ago,” he said. “People like founding park director Gladys Nelker and original horticulturist Tony Dove played an instrumental role in making this site a place of wonder and joy for so many people.”

Other lectures will include topics detailing the almshouse period, archaeology, and the array of plant life on display in the four-season gardens. More information about programs and events is at www.historiclondontown.org/events.