Filling a Color Gap in Maryland History

Ann Widdifield’s Passing Through Shady Side, published with AuthorHouse in 2013

Billy Poe’s African-Americans of Calvert County, published by Acadia House in 2008

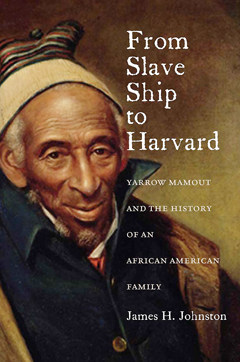

James Johnston’s From Slave Ship to Harvard, published by Fordham University Press in 2012

by Sandra Olivetti Martin, Bay Weekly Editor, with Terri Boddorff and Cameron Caswell, Anne Arundel County Public Library; Beverly Izzy and Robbie McGaughran, Calvert County Public Library

People from Africa and from Europe have been neighbors for many centuries in Chesapeake Country.

Yet for most of our shared time, black and white communities have existed in parallel universes, divided by the harsh economy of race.

From settlement to the end of slavery in the 19th century, half a million slaves were imported to North America.

Paging Through

|

By 1770, 80,000 Africans worked in tobacco colonies. Maryland was the second largest slaveholding colony. By 1790, 101,264 of Maryland’s 319,728 people were slaves, approaching today’s black-white demographic breakdown. In Anne Arundel, 10,130 of 22,598 people were slaves.

They got the worst and least of everything, and their stories have been the last told. Black History Month encourages restitution on one of those scores.

This year, we update you on books featuring African American Marylanders, heading our list with a brand new book set in Southern Anne Arundel County. Passing Through Shady Side joins African-Americans of Calvert County in enriching our knowledge of Chesapeake Country. From Slave Ship to Harvard, beginning in Annapolis, adds the depth of a sixth generational look at one family.

You’ll find introductions to those books and more this week.

You can see the terrain of which the authors write in county-by-county maps produced by the African American Department of the Enoch Pratt Library in Baltimore.

To guide you to more books on African American life in Anne Arundel and Calvert County, public librarians have searched their shelves and catalogues. You’ll find their lists here, too.

Passing Through Shady Side

“Three types of people have passed through Shady Side,” writes Anne Widdifield. The retired school teacher and Annapolis tour guide is of the third type: “those who visited and returned to live.” A fascinated latecomer, Widdifield dedicated four years to documenting the passing through of the first type, “those born here who never left.”

She chose her black neighbors and their ancestors “to balance the story because that’s what was lacking,” she said. “The books done so far told about whites like Miss Ethel Andrews and her family’s hotel. I learned that there were black boarding houses too, and black people coming down [from Baltimore] on the steamship Emma Giles, though they had to stay outside.”

That’s one of a thousand insults and injuries Widdifield chronicles in universes that were separate but far from equal from settlement through the late 20th century.

Yet Shady Side, she tells us, has been “probably one of the better places for blacks to live.” Free families flourished, owned property, made a living off the land and water, gathered in strong churches and, in time, went to school and got jobs beyond day work.

As did Eliza ‘Miss Doll Baby’ Dennis at the urgings of a local pastor: “You’re educated; you’re a high school graduate. You should be doing more than day work. You should get another job,” he told her. And she did.

Miss Doll Baby joined Buddy Holland and Chuck Gross plus members of four extended families — the Nicks, Crowner, Matthews and Thompsons — in telling their story to Widdifield. A double outsider — white and from Indiana by way of Virginia — Widdifield succeeded through curiosity, constancy and connections.

Her journey through the history of her adopted community began in the archives of Captain Avery Museum, founded as the Shady Side Rural Heritage Society in the mid-1980s by newcomers who recorded and collected the lives and artifacts of Shady Siders. Hearing those stories, many as videotaped interviews, made Widdifield hungry for more.

St. Matthew’s United Methodist Church — a black church that stands alongside Shady Side’s white United Methodist church — took her in, and she remains a member of its congregation.

Then, too, she was everywhere.

“I’m a speed walker,” she says, “and I’d start out on my walk and I’d see somebody and talk. But then I’m like that. I’m a talker.”

Half the book’s 20 chapters are the stories of people, told in the loose, conversational style Widdifield heard them.

Nine more describe institutions. Schools, boarding houses and post offices, stores and businesses, neighborhoods and churches, athletics and recreation take shape through the words of people whose lives they touched.

To add the context out of which their families grew, Widdifield read local and state archives.

Watermen are so much a part of Shady Side that they earn their own chapter. Hogs must have been pretty important, too, as one of the chapters is devoted to Hog Stories.

Widdifield writes a nice style and has done her subjects, book and readers the favor of working with an editor, neighbor Jackie Fox Ibrahim. Alas, there is no index to guide us to people and places.

You meet hundreds of people, hear scores of good stories, see dozens of photos and gather a store of facts. You learn that Shady Side was too marshy to grow tobacco, but tomatoes loved the Great Swamp and canneries followed. That Babe Ruth slept in Shady Side and went fishing. And that in one society, that of the watermen “everything was equal.”

Mapping Our African American Experience

|

If you want to meet your neighbors, Passing Through Shady Side is worth your time.

Meet Widdifleld, buy your copy and get it signed at St. Matthews United Methodist Church, Shady Side, on March 9 from 2-4pm. rsvp: 410-867-4486. Book sales benefit the Captain Avery Museum.

African-Americans of Calvert County

Like Shady Side, Calvert County developed through the centuries as parallel black and white communities. Its black population — which has dropped from 62.4 percent in 1850 to 13 percent — rose from slavery, achieved freedom —through manumission, purchase or emancipation — worked the land, the water and in service, bought property and founded churches and schools, living full if hard and largely unstoried lives.

In modern times, Calvert’s African Americans found a willing listener in Billy Poe, a white D.C. kid newly moved to the country.

“Our house was in between the homes of two African American farmers,” Poe told Margaret Tearman for Bay Weekly. “I would sit for hours and hours, listening to their stories.”

Listening became a way of life for Poe. Oral historian, essayist, photographer and poet, he continues the circle of stories with books, documentaries in photo and film, public presentations and a foundation, I Am Somebody, to give scholarships to the children of farmers who had to give up school for work.

“I learned much as I made my way through the roads of Calvert County, knocking on doors and asking for interviews,” Poe writes in the introduction to his 2008 book, African-Americans of Calvert County. “I am always greeted with colorblind eyes and made to feel welcome. … This is a community of family whether by blood, marriage or friendship.”

Community is Poe’s subject in African-Americans of Calvert County. From people’s recollections, historic photos, newspaper clippings and archival records, he has pieced together a history of the whole community in four broad chapters: Servicemen, Matrimony, Education and the Community.

The 128-page book has the immediacy of a well-annotated family scrapbook. Its historic photos capture life as it was lived in fleeting, vivid moments. Poe’s annotations based on hundreds of hours of interviews fill in the context.

Meet Poe at Calvert Library Prince Frederick on March 9 from 2:30 to 4pm. See his photos of African Americans in Calvert on display at Calvert Library Prince Frederick through March 9.

From Slave Ship to Harvard

James Johnson’s From Slave Ship to Harvard is a captivating, true narrative of six generations of an African American family that begins with Yarrow Mamout, a Muslim from West Africa who was brought to the docks in Annapolis in 1752 as a slave and gained his freedom 44 years later.

In contrast to the void of documentation during this period of American history, Yarrow was so well known in his time and community, Georgetown of Washington, D.C., that he was painted by Charles Willson Peale. You’ll see the 1819 portrait — housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art — that immortalized him on the cover of Johnson’s book.

Johnson, a second-career writer and D.C. lawyer, was drawn by the character and into the story still another portrait. Out of painstaking genealogical digging through interviews, wills, inventories, deeds, photographs and other historical artifacts, he has constructed a fascinating family saga. The story weaves its way through 175 years of history and many notable geographic areas and people of Maryland and Washington, D.C. Its culmination is the 1927 graduation from Harvard of Robert Turner Ford, whose lineage is traced to Yarrow through his wife’s family.

Johnston has admirably sought to connect the dots of the family’s history while also providing parallels to the larger story of slavery and emancipation in colonial America. His 2012 book stands apart for giving readers the depth and unity of a family story of rising fortunes in its 310 pages with 25 black and white illustrations.

Meet Johnson at the Annapolis Book Festival on April 13 at Key School, Annapolis.