Getting to Know the War of 1812

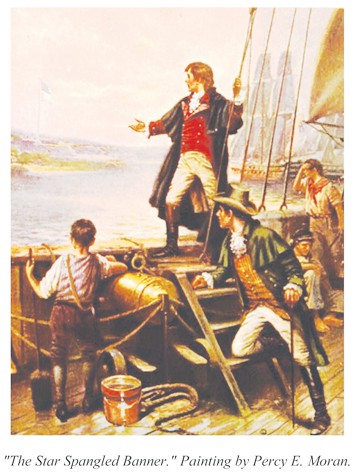

The Chesapeake Bay played a starring role in the conflict that produced our national anthem. Francis Scott Key wrote The Star Spangled Banner as the city of Baltimore was under attack by a vast enemy fleet and army that had just destroyed the new capital, Washington City.

1812 was a long time ago. High tech was represented by small, wooden sailing vessels, powered by wind and sweat, technology little changed in hundreds of years. You want to talk to Europe? Could take months.

But loyalty, courage, compassion, greed, these have changed little. Heroism and genius to a high degree — as well as rank cowardice, slavery, treason and occasional idiocy — were shown by the men and women of the Chesapeake who shaped our modern world.

We face the same basic human conflicts today. When or how to use force, how to fight for human and national rights against oppression, slavery, piracy.

Here is the least you need to know in 15 vignettes, mostly set along the Chesapeake. Our 15 stars represent the 15 stars (and stripes) on the Star Spangled Banner.

1. 1812, Loosely: The war of 1812 should have started in 1807 and did not exactly end in 1814, when Francis Scott Key wrote The Star Spangled Banner.

2. The Man Behind It All: You might call Napoleon Bonaparte the remote cause of the War of 1812. The Emperor of the World had already intervened in American history by selling us Louisiana, all the land west of the Mississippi to, roughly, the continental divide. He funded his continental wars with that purchase price, eventually grappling with England on the high seas.

Both France and Britain felt free to accost and board ships of other nations.

3. Two Big Reasons for War: Impressment of thousands of United States citizens and denial of freedom of trade on the sea.

Great Britain ruled the waves with the world’s largest navy, 600 warships. She was ship rich but sailor poor. To man her worldwide war to the death with Napoleon, Britain impressed — think kidnapped or shanghaied — our sailors into her fleet. Our sailors were forced to serve in the British navy and become “slaves to the lash.”

Our sailors were merchant sailors aboard thousands of ships trading around the world. The new and not very United States of America had a small army and a navy of only 20 ships.

One example: On June 22, 1807, the British warship Leopard attacked U.S. Navy warship Chesapeake, killing and impressing its sailors. President Thomas Jefferson declared a trade embargo that boomeranged, destroying U.S. shipping but not impressment.

4. Meanwhile, Back in the Wilderness: Americans were expanding westward into the frontier wilderness, places like Indiana and great big Louisiana, explored by Lewis and Clark. From its continental stronghold in Canada, Britain encouraged Indians to attack settlers. That suspicion made a third reason for war.

5. Name Dropping: Elizabeth Patterson, the richest and most beautiful woman in Baltimore, was wooed and won by Jerome Bonaparte, younger brother of Napoleon, after Naval hero Joshua Barney introduced the two in 1803. Threatened with disinheritance by big brother, Jerome abandoned pregnant wife Betsy in 1805 for a German princess.

6. June 18, 1812: President No. 4, James Madison, asked Congress to declare war against Great Britain. Thus 18 unprepared and not very United States took on the British all over again.

An overachieving nation? We also invaded Canada, thinking it would help bring a quick end to the war.

7. The Pride of Baltimore: In Baltimore, America’s third largest city, ship designers and builders like Joshua Humphreys, Thomas Kemp and Josiah Fox — Quakers all — created flyers that quickly evolved into clipper ships, the fastest sailing ships ever built, to harass the British on the high seas and along their own coast.

Aboard the topsail schooner Rossie, privateer captain Joshua Barney — one of the most colorful heroes in Maryland history — captured 15 British merchantmen worth more than $1 million — $20 million in today’s dollars.

In 1814, the most successful privateersman, Captain Thomas Boyle, captured 23 British ships worth more than $600 million by today’s standards. Boyle’s schooner USS Chasseur was nicknamed The Pride of Baltimore by local admirers.

8. Old Ironsides: July-August 1812: The 44-gun U. S. Naval ship Constitution destroyed the British Navy frigate Guerriere, earning the nickname Old Ironsides when 18-pound cannon balls bounced off her thick oak sides. Great Britain’s loss of a frigate was trivial; her loss to the puny U.S. Navy was a shock to a nation that had destroyed or blockaded all the great navies of the world.

Today the Constitution resides in Boston; her sister ship, the Constellation, resides in Baltimore harbor.

9. U.S. Victories at Sea: October-December 1812: American warship Wasp captured British warship Frolic. American frigate United States captured British Macedonian. Old Ironsides destroyed another British warship, the frigate Java.

January 1813: New Navy Secretary William Jones knew his business. He ordered more small Navy warships to attack merchant ships, the British Achilles’ heel.

February 24, 1813: Chesapeake-built small Navy warship Hornet, commanded by James Lawrence, destroyed still another British Navy warship, the brig Peacock.

10. Reversals: May 3, 1813: British Navy Admiral Cockburn’s warships and British regulars attacked, raided and burned Chesapeake shores, including Havre de Grace and St. Michaels.

June 1813: While fighting British frigate Shannon, American captain James Lawrence of the frigate Chesapeake uttered his dying rallying cry: Don’t give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks. But the ship is given up, boarded, defeated.

11. Fortune’s Downturn: Along the U.S. coast, the British blockade tightened. By February 1814, the U.S. frigates, President, Constellation, United States Congress and Chesapeake were mostly captured or bottled up, sometimes useful for harbor defense. The only one to escape and plague the British Navy once again was Old Ironsides, the frigate Constitution.

As the British blockade tightened, only privateers and the smaller U.S. navy warships remained active. The American economy virtually collapsed.

12. Invasion: August 1814: British troops invaded from the Patuxent River at Benedict.

August 24: American militia defending the U.S. capital were routed at Bladensburg; only Joshua Barney (who will die of his wounds) and his flotilla crew, which had managed to land their guns and burn their boats, make a heroic stand on St. Leonard’s Creek in Calvert County.

That night the British burned and looted Washington City.

First Lady Dolley Madison stayed behind to rescue the famous Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington and other irreplaceables. The British later dined in the White House and mockingly toasted their absent hosts.

But that ebb tide was shortly to turn, right here on our Bay.

13. So Gallantly Streaming: Mary Pickersgill was paid $500 to make a flag for Fort McHenry so big that enemy ships could see it as they attacked. Her flag had 15 stars and 15 stripes, though the nation had 18 states at the time. She worked and lived at what is now Flag House in Baltimore. The flag itself is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. Explore it at http://americanhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner.

The British fleet sailed up the Patapsco to bombard Fort McHenry. Attacks by land and sea failed, and Francis Scott Key — there by the chance of an errand — wrote The Defense of Fort McHenry, aka The Star Spangled Banner.

14. Peace: Status quo Ante Bellum: On December 24, 1814, the Peace Treaty of Ghent was signed, agreeing to nothing except status quo ante bellum (pretend it never happened). On February 17, 1815, Madison signed the treaty and declared hostilities officially ended.

15. The Battle of New Orleans: On January 8, 1815, in New Orleans, General Andrew Jackson’s army defeated the vaunted British invaders, who lost nearly 2,000 in by far the bloodiest day of the water for the British. U.S. forces lost 20 men.

Fighting continued until official announcements of the peace reached Indiana and Louisiana and even more remote corners of the war. Conflict at sea continued until June 1815.

|

Local author Bert Hubinger, contributor to the Journal of the War of 1812 and author of the novel 1812: Rights of Passage, teaches writing, history and sailing, dives on shipwrecks and has written numerous fiction and non-fiction works: [email protected].