Long Distance Caller

Stakes were high and tension palpable New Year’s Day at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, as Sarah Hamilton and her colleagues waited for a long-distance radio transmission confirming either a successful mission or a failure.

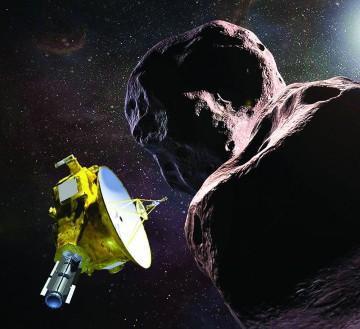

About 10 hours earlier, the New Horizons spacecraft — launched 13 years ago on a mission to Pluto and beyond — had flown past a 20-mile-long object called Ultima Thule (pronounced Ultima too-lee). From four billion miles away, it takes hours for the signals to reach earth. In Mission Control and in the auditorium at APL, people waited for New Horizons to phone home.

Hamilton, an aerospace and software engineer living in Crofton, had tended to the New Horizons spacecraft since 2005, a year before its launch.

She knew from experience that the best-laid plans could go bust in an instant.

On her first assignment at the Johns Hopkins lab, the University of Maryland graduate worked in Mission Control for a NASA space probe called Contour. Its job was to gather data while flying by comets. Like the New Horizons spacecraft that would follow, Contour was designed to receive a set of commands from Mission Control, execute them, then radio back to confirm the commands had been followed.

In August of 2002, nine weeks after Contour’s launch, the Mission Control team sent it a set of commands that would initiate an engine burn and send the spacecraft into a solar orbit.

“You could feel the tension in the room,” Hamilton remembered, as the team waited for a call home that never came. Sometime after contact was lost, telescopes detected debris where Contour should have been. The mission was a near total loss.

Missions into deep space remain, like Apollo 1 through 13, acts of faith. Humans from planners to designers to engineers, fabricators and programmers do everything they can to create machines to act as mobile eyes and ears millions of miles distant. Then they launch their creation. If the launch is successful, their baby travels far beyond human reach over huge distances of space and time where they can guide it only by remote-control.

Four infrastructure subsystems control New Horizons and its seven onboard instrument systems, cameras and other sensors. All these systems need to be told what to do; Hamilton builds and tests the strings of commands to accomplish these goals.

Every couple of weeks, a new set of commands is sent to New Horizons; then comes the tense waiting out the hours it takes the commands to arrive, and the hours it takes the spacecraft to respond that all is well.

New Horizons had survived 13 years and four billion miles in space, but disaster was never out of reach.

Mission: Pluto

In July of 2015, New Horizons approached its first mission objective, an encounter with Pluto. Ten days before the fly-by, a routine command sequence had been uploaded. Then listeners in Laurel waited for hours for the signals to make their round trip.

To paraphrase, New Horizons said, “my main processor is overloaded, I have switched to my backup processor, and I’m running in safe mode.”

The spacecraft was communicating and functioning at a basic level. But in 10 days, when it reached Pluto, it would need to be fully functional.

There was no such thing as turning around and going back for a second pass. If they weren’t ready when they flew by Pluto, the mission would fail.

Memories of that fateful message are still vivid for Hamilton.

“When the processor overloaded on July 4, I was at home checking my work email for confirmation that the fly-by sequence was safely onboard the spacecraft, stored in memory,” she recalled. “I had a bad feeling when the email didn’t arrive. I was in shock as if time was standing still when I first heard the news. I said goodbye to my family as they headed to the fireworks.”

“The team was amazing. It was July 4, but the mission was still priority one, regardless of any plans people might have had. Everyone did what needed to be done.”

It took three days and nights, but the problem was fixed, the fly-by was a success, and we now know more about Pluto than we ever did.

A bumper sticker on Hamilton’s car reads My other vehicle explored Pluto.

Onward to Ultima Thule

After the Pluto mission’s outstanding success, the spacecraft remained in good health with ample fuel and power. A new target was needed, and though Ultima Thule had not been discovered when New Horizons was launched, it was now the choice, a billion miles and three and one-half years away. Hamilton went to work on the command sequence to send New Horizon to its new destination.

The Final Approach

As the moment of the fly-by approached — 12:33am EST on New Year’s Day 2019 — the energy level at the applied Physics Lab ramped up. For Hamilton, it was the climax of 14 years of work. Longer still for some on the program.

“This mission has always been about delayed gratification,” Alan Stern, the mission’s principal investigator, told the assembly at the pre-fly-by briefing on December 31. “It took us 12 years to sell the spacecraft, five years to build it and 13 years to get here.”

On December 20, Hamilton uploaded the final command sequence for the fly-by. Twelve hours later, New Horizons responded that all was well. From December 26 to 31, the navigation team reworked their calculations for a critical parameter, the time of arrival at Ultima Thule.

Hamilton and the Missions Operations team were sending this new data to the spacecraft. The corrections were only in the two-second range, but when you’re traveling nine miles a second and aiming to fly by an object only 20 miles long, that two seconds can make the difference between a perfect picture and a blank frame.

On the morning of Sunday, December 30, the last command sequence was sent. Then Hamilton and her cohorts began to wait for the call home.

On New Year’s Eve, she brought her family to the main auditorium to celebrate the new year, the mission and — they hoped — success.

That night, there were two countdowns: one to midnight, and the other leading up to the fly-by at 12:33am.

It might have been hard for Sarah to explain to her daughters, ages seven and five, what all the excitement was about. But she gave them the key message: “I like my job, I love going to work. You can be anything you want to be and have a job you love, too.”

Then most everyone went home to get some rest before the next morning revealed whether this 30-year quest was a failure or a success.

New Year’s Day

The auditorium was subdued as the New Horizons team, their friends and families and reporters stared at the large screen focused on the Mission Control room, waiting for that phone call home. Suddenly, the auditorium went quiet as we sensed a change in the demeanor of the people in the control room. It was happening.

At their computers, controllers narrated their reports — in technical jargon, of course. After one group reported its status as “nominal,” the crowd’s voice rose.

“We have a healthy spacecraft,” Missions Operations Manager Alice Bowman reported. Then the crowd went wild. Me, too.

Hamilton didn’t have to wait so long. “I was watching the telecommunications subsystems engineers,” she told me. “When I saw them smile, I knew we had data coming back, and the spacecraft was okay.”

New Horizons had extended human reach four billion miles into the universe.

Learn more about the New Horizons mission and the Ultima Thule fly-by in the PBS science series NOVA; Season 46, Episode 1: Pluto and Beyond. Check your local listings or On Demand, or watch it online at www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/video/pluto-and-beyond.