Chesapeake Bay's Independent Newspaper ~ Since 1993

1629 Forest Drive, Annapolis, MD 21403 ~ 410-626-9888

Volume xviii, Issue 30 ~ July 29 - August 4, 2010

Home \\ Correspondence \\ from the Editor \\ Submit a Letter \\ Classifieds \\ Contact Us

Best of the Bay \\ Dining Guide \\ Home & Garden Guide \\ Archives \\ Distribution \\ Advertising![]()

![]() Spotlight on Theatre

Spotlight on Theatre

|

|

|

![]()

In some plays you understand a character by dialogue, and in better plays through actions. But with the best, you know which way the wind blows from the moment a character walks on stage. So it is with Ben Carr and Jim Reiter, the pillars of Colonial Players’ Dog Logic, a dark comedy by Tom Strelich, playing through June 26.

As the brilliant but brain-damaged manic with the heart of a dog, Carr has the audience eating out of his hand within the first minute of his opening monologue. He has a lot of those, monologues addressed to anyone who happens to be listening, where he rants and philosophizes about history and human nature, there on the grounds of his parched pet cemetery amid the detritus of bald tires and garden statues and dozens of decrepit televisions and mounds of bric-a-brac.

There’s a copy of Rodin’s Thinker crowning it all, and that would be protagonist Hertel Daggett, himself. You’ve seen street people like this, but he’s different: so cute and funny, so vulnerable yet competent, so confused but crazy like a fox, honest, escapist, sweet and scary. His mind is a junkyard of symbology and trivia about dinosaurs and cavemen, TVs, amoebas, volcanoes, Godzilla and dogs. Especially dinosaurs and dogs. He’s in touch with his primal roots, a master of survival who lives my instinct while craving love.

Enter Dale (Reiter), a smarmy and profane wheeler-dealer in a cheap polyester suit, who wants Hertel’s commercially valuable wasteland.

“If you could have anything you wanted,” he asks, “and don’t think about how much it costs, what would it be?”

Clearly, he has picked the wrong target, but he is nothing if not persistent. He’s also not as bright as his prey, but that won’t matter once he enlists the help of Hertel’s estranged wife and his mother, who would be all too happy to force the sale.

Kaye (Shirley Panek) is the sheriff in town, and coincidentally Hertel’s ex-wife: a hard-nosed and practical force for order with a sympathetic ear and an appreciation for the financial freedom Dale offers. Torn between abiding affection for Hertel and frustration at his candidness and inherent lack of ambition, she worries over him like a mother, a relation he’s been missing.

Mother Anita (Kathryn Huston), who flew the coop when he was little, mysteriously reappears soon after Dale’s visit. She’s got quite a checkered history of her own, the most salient part being where she “drifted away from God and got into real estate.” If Hertel has a dog’s intuition, Anita has the business acumen of a pit bull, but she’s so cool and charming about it we trust her.

Colonial Players have mounted a fine production that, being light on visual and sound effect, relies almost exclusively on the ability of four actors. Carr and Reiter are brilliant, while Panek and Huston turn in solid portrayals of complex women. The only frustrating thing about this show is some of the blocking. Since Colonial’s is a theater in the round, particular attention must be paid to all four sides of the audience. Those seated in section C see more of Hertel’s back than his face, and when he lies down center stage to deliver a long speech, he is obscured by props.

Hertel defends his obstinacy with a bold statement; “There is an obligation that we have to the things we have loved.” This play ferrets out the believers from the fakers while addressing the roots of our modern evolutionary discontent: our obligation to all things living and loved amid mounting materialism and progress. Entertaining and provocative, this is a play you won’t soon forget.

Directed by Carol Youmans. Set by Carol Youmans and Dick Whaley. Costumes by Julie Bays. Lights by Andrea Elward. Sound by David Colburn. Stage manager: Herb Elkin. June 17 thru 26

Playing thru June 26 at 8pm Th-Sa; 2pm June 20 and 26; and 7:30pm June 20 at Colonial Players, 108 East St., Annapolis. rsvp; $20: 410-268-7373; www.cplayers.com.

2nd Star Productions’ The Secret Garden

Come to this garden. It’s a beautiful place.

W. Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic children’s tale The Secret Garden has delighted readers and audiences for over a century. Marsha Norman and Lucy Simon’s 1991 musical adaptation transforms it into a visceral experience that 2nd Star Productions delivers in a heady spray of song and drama. This musical drips with lush, hummable melodies whose subtle dissonances save it from predictable sweetness.

|

|

![]() In this G-rated ghost story, an orphan’s benign ancestral spirits guide her to a healing garden that restores her broken family, physically and mentally. It’s Disneyesque but sophisticated enough for mature audiences, so it is fitting that the youth in this production shine as brightly as the adults.

In this G-rated ghost story, an orphan’s benign ancestral spirits guide her to a healing garden that restores her broken family, physically and mentally. It’s Disneyesque but sophisticated enough for mature audiences, so it is fitting that the youth in this production shine as brightly as the adults.

Chief among them are rising stars Vivian Wingard as the orphan Mary Lennox and Zachary Fadler as her friend Dickon. Wingard is a rosebud waiting to bloom: a charming actress, graceful dancer and accomplished singer with a pure, unspoiled sound. She is refreshingly innocent yet capable of holding her own against a cast of old pros. It is Fadler, however, who steals the show as Dickon, Mary’s best friend. When he enters in “Winter’s on the Wing,” all else disappears under the spell of his exuberance and vocal edge. Warmth is palpable when he sings it in in “Wick.”

Equally compelling is Mary Dickson, who plays Dickon’s sister Martha, the maid. Her effortless mezzo is as inspirational and grounded as a mother’s embrace, notably in Act One’s “A Fine White Horse” and her blockbuster finale “Hold On.”

Working folk aside, Mary feels unloved and alone. Her cold Uncle Archibald Craven (Eddie Chell) is haunted by Mary’s resemblance to his deceased Lily, the wife his brother Neville (John Dickson) also loved from afar. These two fine actors and singers set a solemn tone for the show’s most memorable music: “A Bit of Earth,” “Lily’s Eyes,” “Quartet” and “Where in the World.” Dickson’s voice is resonant and authoritative in both speech and song, but most compelling in the lilting Irish tenor melody, “Disappear.”

The situation is complicated by the congenital illness of Archibald’s only child, who barely knows his father thanks to Dr. Neville’s overprotective care. Austin McKinnis’ hypochondriacal Colin (double cast with Gabe Needle) is perfectly obnoxious, hardy of spirit but otherwise frail.

An excellent Greek chorus of omniscient ghosts is omnipresent and too numerous to mention by name, but Kevin Cleaver as Captain Lennox has the most haunting voice and bearing. Samantha Feikema as Lily Craven has the most daunting role and operatic style, with a piercing coloratura reminiscent of Sarah Brightman. But lovely as is her solo “Come to My Garden,” her voice does not blend in chorus. Malarie Novotny as Mrs. Medlock is another highlight of an already bright ensemble. Opening night also featured a fine surprise performance by co-director Brian Douglas as Major Holmes. Cheramie Jackson is a loveable and realistic Mrs. Medlock.

This show is a late bloomer, poorly set by the overture and a rocky opening number. Past its initial awkwardness, it captivates. A piccolo’s birdsong brings the outdoors inside, and a magical sense of time and place is achieved with exquisite costumes, décor and choreography. The English furnishings and tapestry look like they belong at Sotheby’s. The Indian Shiva dance in “Come Spirit Come Charm” with Ayah (Ruta Kidolis) and Fakir (Michael Mathes) is as exotic as incense. “Come to My Garden,” Lily beckons with good reason. It’s a beautiful place.

Director and set designer: Jane B. Wingard. Musical director: Joe Biddle. Lights and sound: Garrett R. Hyde. Costumes: Linda Swan.

Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre’s

Forever Plaid

The Plaids score again and again in pursuit of that “one perfect chord that bursts out into the galaxy.”

|

|

When Stuart Ross’ Doo Wop revue Forever Plaid took Annapolis by storm two years ago, so, unfortunately, did the weather. Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre under the stars could not meet the demand for tickets amidst a stalled front of cloudbursts that cancelled a third of the performances. So The Plaids have been reincarnated once again for “the biggest comeback since Lazarus.”

That’s right, the adorable foursome of Frankie (Peter N. Crews), Smudge (Nathan Bowen), Jinx (Kyle Peter Van Zandt) and Sparky (Trent Goldsmith) is back until June 13. And holy cannoli, with the entire artistic team returning to help them, along with two years’ maturation and reflection, the result is near perfection. It’s smoother, more stylized and funnier than ever. After all, as Jinx says, “Once you know your part, you can hold onto it forever.”

The Plaids, crooners on the cusp of semi-fame in 1964 when their lives were cut short by a collision with irony, return to earth via a Twilight Zonish twist of space and time that allows them to give one last performance as the stars they were on their way to becoming. It’s the show of a lifetime, along with a peek back at male friendship before it became bromance.

The changes this time around are subtle. Visual effects emphasize the ethereal storyline with celestial scenery and eerier lighting. The Plaids enter through the audience rather than onstage. Vocal arrangements are more ornamented. The characters are more clearly defined in their quirks and ailments. Crews’ Frankie, the eldest and de facto front man, leads with greater authority — when he’s not having an asthma attack. Van Zandt’s Jinx, the youngest and shyest, appears more confident in his character and himself — when he’s not suffering from nosebleeds. Bowen’s Smudge is more of a worrier, given to bouts of indigestion, and Goldsmith’s Sparky is more mischievous as well as the most perfectly period looking character. They are a convincing brotherhood in harmony, despite their age gap.

This show is hilarious for depicting an era that took itself far more seriously, even in its silliness, than modern audiences ever will. Beyond comedy, its playful choreography and lush arrangements of pop classics are loveable. The Plaids score again and again in pursuit of that “one perfect chord that bursts out into the galaxy.”

Bowen’s robust bass and Crew’s stylized showmanship sell the “Sixteen Tons” and “Chain Gang” medley better than the originals. Van Zandt’s “Cry” is a study in dynamic contrasts and control that showcases his pure tenor. Goldsmith’s “Perfidia” feels exotic and stirring, though he did suffer passing pitch problems in a few solos. Individually, they are impressive; together, they are divine.

Other show stoppers include “Crazy ‘Bout Ya Baby,” choreographed with plungers whose improved suction give a satisfying fwup sound that was lacking last time; the Caribbean Plaid medley, including “Day-o” and “Matilda,” offers visually dramatic silhouettes and audience participation fun; and “Heart and Soul” features a guest pianist from the audience who is richly rewarded with plaid thank-you gifts. My favorite musical moment, though, is “Scotland the Brave” for its haunting harmonies.

According to Smudge, you can take it with you when you die. You’re allowed one suitcase, and his is full of favorite records. Mine will include the soundtrack to this show.

Read more about this show see 2008’s review at http://www.bayweekly.com/reviews2008.html. It’s the 12th item down on the page.

Playing thru June 13 at 8:30pm Th-Su at Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre, 143 Compromise St., Annapolis. $18: 410-268-9212; www.summergarden.com.

Director and set designer: Jerry Vess. Musical director: Barbara Markey. Choreography: Amber Clare Perkins and Peter N. Crews. Keyboard and drums: Ken Kimble and Larry Berry.

Colonial Players’ Mrs. California

Despite fine work, this play can’t quite figure out what to make of women in America’s 1950s.

, May 13, 2010

, May 13, 2010

Colonial Players of Annapolis always gets the extra touches right, but those grace notes rarely get noticed.

This review is the exception.

Let us praise the lobby display work of Wes Bedsworth and Jason Vaughn in support of Mrs. California. From seemingly vintage posters to a video loop of 1950s’ commercials, cartoons and I Love Lucy episodes, the ambiance of the 1955 Belvedere hotel is set before the audience leaves the lobby.

Inside the theater, the floor painting by Doug Dawson and Mike Monda is spectacular, vividly replicating ‘50s’ carpet motifs and parquet flooring. The set focuses on four stations at which a homemaker’s contest takes place. Call the stations transformer homes, because they each transform into a dining table, a kitchen stove and fridge, an ironing board and a sewing machine. Set designers Doug Dawson and Dick Whaley have created an engineering and artistic marvel.

The show itself I am not so pleased with. Its purpose is given away in the opening monologue, which weakens the script. The premise of a homemakers’ contest being televised for the first time, with sponsors manipulating the homemakers, could be very effective.

The new field of marketing flexed tremendous power in making changes in women’s work palatable to women themselves and to society. Ads during the war targeted assembly line workers, promoting the value of quick, simple, casserole dishes to feed a family. After the war, ads targeted to the same women, now at home, promoted expansive, three-meal courses that took hours to prepare.

The context is rich, but Mrs. California doesn’t quite make the grade. It never seems to decide whether to be broad comedy, political statement or character study.

As a comedy it has some wonderful moments, with perfect timing from the quintet of actresses leading the show. Mrs. Modesto, played by Karen Lambert, comes closest to the Lucille Ball goal of broad comedy melded with a touchingly vulnerable character. Mrs. San Bernadino, played by Monica Anselm, reacts wordlessly to actions around her and does so expressively and skillfully. Mrs. San Francisco, played by Jane Elkin, is the social climber of the competing women, enamored of all things foreign. Stronger projection would have clarified some of Mrs. San Francisco’s dialogue and made more sense of her character’s quirks.

Mrs. Los Angeles is the focal point for Mrs. California. She is a competent woman, in decoding war messages or ironing a shirt. The question becomes whether the ironing skill is what she wants remembered about her. Pam Peach makes the role work, and her comedic timing keeps events unfolding.

Mrs. Los Angeles’ best friend is Babs, an overwritten character that Erin Leigh Casey does her best to humanize. Babs is meant to be the political voice and contrast to the four competing women. But down to her clothing and hairstyle (a bit more 1980s than the 1950s’ Mary Tyler Moore she is obviously meant to resemble) she just doesn’t seem of the era. Casey has energy and bravado to carry the character; too bad the character can’t return the favor.

Rounding out the cast are Kathryn Huston and Timothy Sayles, amusing as the judges; Danny Brooks, effective as stage manager and show emcee; and Erik W. Alexis as Dudley the gas company sponsor.

Mrs. California doesn’t win the crown, but it does raise questions of values and remembrances, and which are real and which are merely nostalgia, possibly phony nostalgia at that.

Written by Doris Baizley. Directed by Judi Wobensmith. Assistant director/stage manager: Mike Monda. Lighting designed by Harvey Hack. Costumes by Jeannie Beall.

Playing thru May 29 at 8pm Th-Sa; 2pm Su & May 29; 7:30pm May 16 @ Colonial Players, 108 East St., Annapolis. $20 w/age discounts: 410-267-6580; www.cplayers.com.

Bay Theatre Company’s Souvenir

You’ll laugh and cry, sometimes simultaneously

Stephen Temperly’s Souvenir: A Fantasia on the Life of Florence Foster Jenkins is one of America’s most produced plays because it’s based on a truth that is stranger than fiction: the musical career of America’s most unlikely box office attraction, a tone-deaf socialite who sold out Carnegie Hall at the age of 76. This intimate evening of witty reflections on bad singing, playing through June 5 at the Bay Theatre, is a must-see, not only for classical music lovers but equally for all of us who ever aspired to greatness or admired someone who did.

|

|

![]() Madame Flo, as her accompanist Cosmé McMoon called her, was a walking caricature: a grand dame, elaborately costumed and bejeweled, who sang in a quavering, belabored screech that was less prima donna than primal scream. A sweet lady who sang for charity and for her love of music, Madame Flo was happily delusional, believing she was greater than the reigning divas of her day: Rosa Ponselle, Luisa Tetrazzini and Kirsten Flagstad. Her blissful ignorance made her, as one critic said, “innocently uproarious” — and vulnerable.

Madame Flo, as her accompanist Cosmé McMoon called her, was a walking caricature: a grand dame, elaborately costumed and bejeweled, who sang in a quavering, belabored screech that was less prima donna than primal scream. A sweet lady who sang for charity and for her love of music, Madame Flo was happily delusional, believing she was greater than the reigning divas of her day: Rosa Ponselle, Luisa Tetrazzini and Kirsten Flagstad. Her blissful ignorance made her, as one critic said, “innocently uproarious” — and vulnerable.

Thus McMoon, an accomplished musician in his own right, found himself drawn into a 12-year partnership that far exceeded their professionally symbiotic relationship. He became her onstage protector and offstage confidante, a sort of Sancho Panza to her Don Quixote. Together they will make you laugh and cry, sometimes simultaneously.

Director Lucinda Merry-Browne chose a stellar duo to fill these formidable shoes. Gael Schaefer as Madame Flo is charming and clueless. Picture a cross between Katherine Hepburn and Karen Black, neither known for their singing, and give her the confidence of a child before she learns the pain of criticism. Schaefer’s performance is noteworthy on another score: It takes a tremendous talent for a competent singer to sing this badly, and to do so with shameless aplomb takes real guts.

As Cosmé, Ralph Petrarca’s musical versatility, witty banter and outsized physical comedy are reminiscent of Steve Allen at his funniest. Petrarca is equally serious when philosophizing on the unlikely turn of fate that made him an also-ran to his untalented patroness.

His sympathy rings true when he rues audiences who “never heard her, but knew enough to laugh.” Bay Theatre’s opening night crowd was no exception. They laughed and hooted, playing along with the joke, making this an interactive theater experience.

If only the grand piano did not overpower Petrarca’s spinet of a singing voice, this show would be perfect. But then, Cosmé would point out that, “What matters most is the music we hear in our head.” Such is Madame Flo’s legacy.

I was not only amused but also intrigued. So piqued was my interest that I frittered away an afternoon researching the pair online. Of particular interest are the 13-part YouTube video Florence Foster Jenkins: A World of Her Own, and the hotly debated rumor that McMoon was in fact a pseudonym for Kirsten Flagstad’s famous accompanist, Edwin McArthur. It’s all interesting fodder for discussion, but irrelevant to the show: a sweet reflection on a shared passion for music and the loving respect of an enduring partnership.

Director: Lucinda Merry-Browne. Costumes: Janet Luby and Joanne Gidos. Set: Ken Sheats and Joanne Gidos. Lights: Steven and Preston Strawn.

Playing thru June 5 at 8pm FSa; 3pm Su (two hours including intermission) @ Bay Theatre, West Garrett Office Building, 275 West St., Annapolis. $30 w/discounts: 410-268-1333; www.baytheatre.org.

Twin Beach Players’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Don’t miss your last chance to see timeless drama — and dysfunction — in Southern Anne Arundel County. It’s hot.

photo by Kevin McAndrewsLuke Woods plays Brick, the alcoholic star of Tennesse Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning play. Brick lives chained to his wife Maggie, a woman he cannot stand, played by Bess Wilkins. The characters are dysfunctional, but the actors are dynamite. |

![]()

“Mendacity is the system we live in. Liquor is one way out, and death is the other.” So says Brick Pollitt, the alcoholic hero of Tennessee Williams’ 1955 Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. If you are inclined to agree, if you wonder what would drive a man to such desperation — or if you just appreciate a classic well-acted, see Twin Beach Players’ production before it ends this weekend. For though its characters may seem dated, their drama and dysfunction, portrayed by some of Southern Anne Arundel County’s finest, are timeless.

Williams had strong opinions about artifice in the American family, and he lays the blame squarely at the dainty feet of some toxic women coated in candy shells, with Brick’s wife Maggie (Bess Wilkins) being one glorious example. A shallow beauty whose sharp tongue and dull vision have driven her husband from her bed, she clings to their public image as the perfect couple: the football hero and the fawning deb. Would that their glory days had lasted beyond the honeymoon — or that she had his child to console her.

But Brick (Luke Woods), like his father before him, is chained to a woman he cannot stand. Big Mama (Elizabeth McWilliams) is just an older and brasher version of her daughter-in-law. Big Daddy (Tom Wines) found refuge in his work and fortune rather than in the bottle.

Brother Gooper (Kevin McAndrews) also married a controlling busybody, Mae (Regan Cashman), who gives him no end of trouble, along with a brood with which to leverage for the lion’s share of the inheritance.

For though Big Daddy may not know it, his days are numbered — and anticipated like a Delta breeze off the Mississippi on a sultry night. Big Daddy jaws at Brick about mortality, morality, covetousness and corruption, trying to break the code of his favorite son’s unspeakable demons — and managing only to deepen the chasm between them.

This is a circumspect drama about sex, taboos and violence, at times so raucous you will want to run from the theater for a moment of peace, just as in a real family squabble. That’s part of what makes it work so well.

But the high energy in this production flows between the two leads. Wilkins sizzles as Maggie, a role she seems born to but in truth assumed only three weeks before opening. As the ex-jock in shock, Woods has perfected what Maggie calls “the charm of the defeated”: the calm exterior that camouflages the volcano simmering within.

Wines and McAndrews also give credible performances.

A historically nomadic troupe, Twin Beach Players is used to making do. This time out, the company has filled some surprisingly big shoes with a shoestring set in a shoebox of a space, the Holland Point Civic Center. Given the high drama and piercing volume of several voices, Big Mama’s chief among them, sit in the back of the room if you value your hearing.

Also featuring Earl Prusia as Rev. Tooker; Phil Cosman as Dr. Baugh; Cheryl Thompson as the maid Sookey; and Molly Prusia, Megan Prusia, and Mickey Cashman as the Pollitt grandchildren Dixie, Trixie and Buster. Director: Gary Adamsen. Set designer: Sid Curl. Light designer: Lauren Kolstad. Costumer: Dawn Dennison.

Playing thru April 25 at 8pm FSa; 3pm Su @ Holland Point Citizens Association Building, 919 Walnut Ave., North Beach. $15: 410-474-4214; www.twinbeachplayers.com.

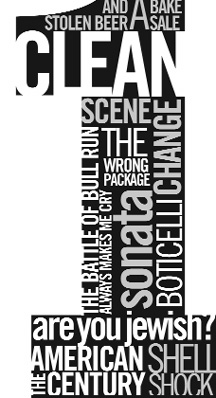

Colonial Players’ I Love You, You’re Perfect,

Now Change

The show’s not perfect, but the cast just about is.

A lot of frothy sweetness, a touch of tart, ample doses of immediate humor and little lasting sustenance sum up I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change, now playing at Colonial Players of Annapolis.

Twenty scenes about relationships and how differently men and women interpret actions and motives make up this musical comedy. Almost all the scenes succeed and are funny; a few are hilarious. But in the end, they are still short comedy sketches set to music. A stronger connective thru-line might have made more lasting impact.

The music varies wildly from blues to rock to Broadway to folk to gospel. Few composers are adept in all these idioms; this one, Jimmy Roberts, seems to be checking off styles to make sure each had been sampled. The lyrics, on the other hand, are uniformly and amazingly clever. For example, the song about ugly bridesmaid dresses, “Always a Bridesmaid,” urges brides-to-be not to pick dresses of taffeta because “they’ll laugh at ya.” A well-known truth wrapped in clever dialogue.

What makes I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change work is the individual and ensemble work of this cast. Virtually all the show is in the hands of a quartet: Jamie Erin Miller, Jeffrey Walter, Shannon Benil and Jeff Sprague. Strong voices, comedic flair and trust make this show succeed.

Sprague has been seen in many other shows, but this one showcases his vocal strength and comedic versatility best. Miller has excellent vocal range and is fearless as a comedian, whether comfortable looking elegant, dorky, matronly or goofy, all within minutes. Benil has an everywoman quality that wins her audience. Her vocal strengths and quick comedic turns are matched by her emotional power in a video-dating scene, which provides the show’s most poignant moments. Walter didn’t start strong on opening night but quickly proved himself the equal to his cast mates. He’s still in high school, making the quality of his work even more impressive.

Normally set design and changeover work at Colonial Players is a highlight. In this instance, however, modifying the set for every one of the 20 scenes felt difficult and a bit distracting.

There is one bit of hilarious blocking that cannot be divulged. Look for the scene entitled “The Family that Drives Together” for a bit of genius.

In the second-to-last scene, the quartet that the audience has come to expect is suddenly replaced by Danny Brooks and Carol Cohen. While the change seems a bit jarring, they portray the romantic sensibilities of older men and women with grace and conviction, creating a lovely coda.

I Love You, You’re Perfect, Now Change captures male-female foibles, relationship angst, longings and desires. While the show itself isn’t perfect, this cast just about is. For an evening of genuine laughter, this is the ticket.

Book and lyrics by Joe DiPietro. Directed by Terry Averill and Mark Hildebrand. Stage managers: Susia Collins and Jeanie Mincher. Lighting designer: Alex Banos. Set designers Terry Averill and Edd Miller. Costume designers Holly Hagelin and Sally Reuter.

Playing thru April 18 at 8pm Th-Sa; 2pm Su; 7:30pm April 11. No performances Easter Weekend. Colonial Players Theater, 108 East St., Annapolis. $20 w/discounts: 410-268-7373; www.cplayers.com.

Second Star Productions’ On Golden Pond

Escape to Golden Pond for the good people you’ll meet there, the memories and the reminders that time is not on your side and that the time for mending fences is now.

With spring in the air, thoughts drift to summer and that perfect little pine-scented cabin where we first learned to paddle, fish or do a backflip. Welcome to 2nd Star Productions’ On Golden Pond, a slice of home that reminds us what we really left behind: family discord. But here the diversions here are more pleasant, and there is always hope for reconciliation. Such is Ernest Thompson’s message that won over television, Broadway — three times — and Hollywood, to the tune of three Oscars.

|

|

Norman Thayer (Edward Kuhl), a retired professor and full-time curmudgeon on the brink of dementia, might be called toxic, particularly where his daughter Chelsea (Rosalie Daelemans) is concerned. Chelsea’s still nursing childhood grudges against her father, thus alienating by extension her mother, the ever-patient and sweet Ethel (Lynne Bouchard). Norman’s only friend, Ethel is loyal to the end, constantly reorienting him from his wrong turns down memory lane and drowning her heartache in coffee and blueberry muffins, which she feeds to the mailman, Charlie (Paul Ballard).

Then Chelsea visits with her new boyfriend, Billy Ray (Dean Davis) and his son Billy Jr. (double cast with Zac Fadler and Michael Mathes), prompting great changes in the Thayer family. Norman and Billy Jr. become great friends, inspired by the other’s wisdom and youth. Chelsea finds love and peace, and the intergenerational lines of communication are opened once again as if by the small town telephone operator herself (Joanne Wilson).

It’s a dramatic comedy the author intended to be an “unsentimental and unflinching study in dysfunction,” which is played all too often as maudlin. But this production is neither. It’s simply flat. Like a CliffsNotes summary of a Robert Frost poem, the themes and metaphors are there, but it lacks the master’s inspirational touch.

Yes, it’s beautiful: Jane B. Wingard’s set is so inviting you’ll want to spend the night curled up on the hearth under the moonlit moose antlers, listening for loons on the lake.

Yes, it’s amusing, particularly when outsiders venture in.

But if anger is the flipside of love, both are lacking in this family. Avoidance of intimacy is the both the topic of this play and its problem. On top of that, Bouchard’s lovely Ethel is 20 years too young for this role.

As for the non-Thayers, though, this supporting cast is terrific. Ballard’s mailman has a contagious laugh and a passable Maine accent, so judged by one who knows. Dean Davis cuts just the right figure as the perfect son-in-law-to-be: charming, intelligent, kind, and totally wise to Norman’s mind games. No wonder Chelsea loves him. Fadler is nothing like the snarky, sullen teen of the film, and his Billy Jr. is all the more loveable for it.

Escape to Golden Pond for the good people you’ll meet there, the memories and the reminders that time is not on your side and that the time for mending fences is now. It may be more of a fish tale than you are willing to swallow, but the fishing is relaxing.

Playing thru March 19 at 8pm ThFSa; 3pm Su @ Bowie Playhouse, Whitemarsh Park, Bowie. $20 w/discounts: 301-832-4819; www.2ndstarproductions.com.

Director: Charles W. Maloney. Set designer: Jane B. Wingard. Light and sound designer: Garrett R. Hyde. Costumer: Joanne Wilson. Stage manager: Joanne Wilson.

Bay Theatre Company’s Mauritius

This action-packed sting will launch you from the edge of your seat to Grandpa’s stamp album in search of buried treasure.

What is a stamp? Currency, artwork, investment, collectibles?

photo courtesy of Bay Theatre Company |

It’s human nature to fill the emptiness of our disappointments, and that’s one reason collectors exist. Some people feed their emptiness with memories, some with revenge and some with material possessions. But some warped souls crave it all. Welcome to Phil’s stamp shop, a shabby place where dreams go to die.

In Theresa Rebeck’s suspenseful drama Mauritius, directed by Steven Carpenter at the Bay Theatre Company, five fractured souls clash over the crown jewels of philately: the one-penny and two-penny misprinted post office stamps of Mauritius. A Broadway hit in 2007, this was the 10th most produced play in regional theatres last year. Rebeck — whose television credits include Law and Order and NYPD Blue — characterizes her plays as “psychologically complicated and having intellectual rigor.” That she delivers here in spades.

This family drama for mature audiences centers on the conflict between estranged half-sisters Jackie (Rana Kay) and Mary (Karen Novack), heiresses to a mountain of debt and dreck, both claiming ownership of their only valuable heirloom, a vintage stamp collection. Jackie claims it was given as payment for nursing their dying mother, while Mary, who has been conspicuously absent, claims it by lineage. Jackie wants to sell what Mary wants to keep. But once the collection’s true value is known, Mary’s motivations are not so clear-cut, and this house divided against itself is game for a triumvirate of predatory dealers.

Their combined expertise, charm and wealth should make each of this trio unstoppable. Yet each insists on thwarting the others. For as one of them notes, “You know what they say about the stamps. It’s the errors that make them valuable. That’s kind of my theory on people.”

Philip (Peter Wray), the acknowledged expert, is so off-putting with his prickly professionalism that he is his own undoing. Thus Dennis (Danny Gavigan), an amateur philatelist and expert con man, is the one to discover Jackie’s treasure. He’s a leech, a hanger-on and a heck of a smooth talker, but he’s broke. So he brokers a deal for Sterling (Nigel Reed), a ruthless psychopath.

In a powerful cast, Kay is by far the strongest performer with her sympathetic protagonist who is by turn naïve and calculating. Novack’s antagonist is just that: an antagonistic, guilting, two-faced thorn in the side whose ability to be so benignly unlikable is a testament to her talent. As for the men, Wray and Gavigan ring true to their roles, but Reed is so one-dimensional that he robs his character of his most shocking moments. Likewise, some of his fight scenes appear too staged.

On the whole, though, this production is engaging, surprising and clever. I only wish Rebeck had addressed the one overarching plot question of legal right in the absence of a written will. Still, this is an action-packed psych-out of a sting that will launch you from the edge of your seat to Grandpa’s stamp album in search of buried treasure.

Set designer: Ken Sheats. Costumer: Christina McAlpine. Light designers: Steven and Preston Strawn. Stage manager: Tupper Stevens.

Playing thru March 20 at 8pm ThFSa; 3pm Su @ Bay Theatre Company, 275 West St., Annapolis. $30 w/discounts: 410-268-1333.

Frozen

This play is a must-see, one of Colonial Players’ strongest. But don’t bring anyone who might be offended by a realistic portrayal of evil.

We’re not talking about weather here. Colonial Players’ Frozen, by Bryony Lavery, is bleak, cold, dark and delving, without reservation, into the world of the criminal psychopath. Its icy theme concerns unspeakable things.

The three principals establish the story with monologues that are intricately layered and interlaced, each complementing the others, drawing the audience ever deeper into the bleak world inhabited by these three. It was not long before I was captured by the story.

![]() Nancy (Mary MacLeod) is the driving force of this powerful drama and a woman frozen in grief. Her opening monologue lays bare the details of her emotional devastation, beginning with the day daughter Rhona left to visit her nearby grandmother. Five years elapse before Rhona’s killer is captured and Nancy learns her fate.

Nancy (Mary MacLeod) is the driving force of this powerful drama and a woman frozen in grief. Her opening monologue lays bare the details of her emotional devastation, beginning with the day daughter Rhona left to visit her nearby grandmother. Five years elapse before Rhona’s killer is captured and Nancy learns her fate.

Psychiatrist Agnetha (Laura E. Gayvert) specializes in criminal behavior. Psychopathic behavior, she argues, is never random; it’s always a result of brain injury. She has come to England to lecture on the subject and study the imprisoned killer of Nancy’s daughter.

Ralph (Thurston Cobb) is the killer; he regrets only that he was caught due to “inefficiency.” He describes how he abducted the child, attempting to excuse himself by saying he only wanted to “keep her for a bit.”

Nancy’s overweening question is Why? But this question evolves into something like How do I get out of this? It’s gone on long enough. Nancy longs to break out of the internal prison in which she has languished. She recognizes the futility of the hatred she feels: hatred of the man, the crime and what it’s done to her life. MacLeod slides effortlessly from deep grief to raw humor and through shades of in-between.

The killer’s role is not quite so complex; Ralph is a true psychopath who needs to have the meaning of the word remorse explained to him. Cobb carries it with a style no less outstanding. In the several scenes where he’s being interviewed by the psychiatrist, his abrupt transitions between rage, resignation and despair combine to form a picture that’s completely believable.

Agnetha fits in the emotional gap between Nancy and Ralph, in that she sees herself as a scientist whose job requires that she tamp down her emotions. She strives to maintain a distanced objective demeanor as she interviews Ralph, but she’s not always successful. Agnetha is eventually drawn into an emotional relationship that should not be. Thus she and Nancy engage in a subtle conflict. Gayvert is perfect in the role; we see her, purely through her facial expressions, struggle with Ralph’s emotional swings and with her own inner conflicts.

In one speech, Nancy opines that she should begin to live “in the moment.” That’s what anyone who watches Frozen will do; you can’t help being pulled in to the moment. The play spans 25 years, but the drama is always in the moment.

With Jim Gallagher’s powerful, professional direction, this play is a must-see, one of Colonial Players’ strongest.

But don’t bring the children. Indeed, don’t bring anyone who might be offended by a realistic portrayal of evil.

Producer: Bob Brewer. Stage Manager: Jacki Null. Costume Designer: Jeannie Beall. Lighting & Set Designer: Eric Lund. Sound Designr: Laurie Nolan.

Playing thru February 27 at 8pm Th-Sa; 2pm Su & Sa Feb. 27 @ Colonial Players, 108 East St., Annapolis. $20 w/discounts: 410-268-7373; www.cplayers.com.

Oklahoma!

Oklahoma!

It may be cold and miserable in Annapolis, but there’ll be a bright golden haze on the meadow at Maryland Hall for the Performing Arts Friday and Saturday Feb. 12-13, when the Annapolis Chorale and Annapolis Chamber Orchestra present Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical Oklahoma! As rousing as it is romantic, this is a proven crowd pleaser that Chorale members have been clamoring to perform since the Broadway in Annapolis series began a decade ago.

The returning cast of popular soloists includes Ashleigh Rabbitt Sekoski as Laurey, Troy Clark as Curly, Katie Hale as Ado Annie and Jason Buckwalter as Will Parker.

This snapshot of pioneer Americana brings us Broadway music as it was meant to be heard and felt, with a full orchestra and lots of dancing cowboys, farmers, saloon girls and sweet young things from the Ballet Theatre of Maryland and the StageWorkz ensemble.

This show is packed with songs you’ve known since the womb, from the title song, “Oklahoma!” to the prairie ode “Oh What a Beautiful Morning” and the coy “People Will Say We’re In Love” to the coquettish “Cain’t Say No.” So don’t be surprised to find yourself humming “The Surrey With the Fringe On Top” while driving home.

Friday, come for a casual performance and a question-and-answer session with the cast. 7:30pm F; 8pm Sa @ Maryland Hall, Annapolis. $37 w/students free at the door as space allows: 410-280-5640; www.marylandhall.org.

|

|

Colonial Players’

The Lion in Winter

What family doesn’t have its ups and downs?

You thought your family holidays were a soap opera? Try Christmasing with King Henry II’s court in1183 as the family celebrates Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine’s furlough from prison with insults, affairs, disinheritance and conspiracy to murder. But, as Eleanor says, “What family doesn’t have its ups and downs?”

History buffs may chafe at its speculative premise, but James Goldman’s clever dialogue has made The Lion in Winter an audience favorite for over 40 years. He paints the fine line between comedy and tragedy like an illuminated manuscript, and Colonial Players’ production is as stunning for its passion and pomp as for its playfulness. Forget the dim sangfroid and cacophonous din of the film, most memorable for Katharine Hepburn and Peter O’Toole’s award-worthy performances. Here the timeless cancers of the soul sparkle like explosive embers in a midnight bonfire.

Wealth and power corrupt, and Henry’s (Kevin Wallace) three sons are willing to risk corruption to get the crown, the British Isles and much of France and the hand of the winsome French Princess Alais (Erin Casey), contractually engaged since childhood to Henry’s eldest son Richard (Pat Reynolds). Henry, however, took Alais as his mistress six years earlier; thus Eleanor’s banishment and the end to one of history’s greatest love stories.

Infidelity Eleanor of Aquitaine can handle, but when Henry threatens to bypass her favorite son, Richard, for their youngest, John (Eric Schaum), she schemes to protect the law of primogeniture. Stirring the pot are Alais’ brother, the boy-king Philip (Josh Greenwald), who hopes to profit from the broken contract, and Henry’s opportunistic middle son, Geoffrey (Ron Giddings), chancellor-in-waiting.

So much is packed into this costume drama that it’s sometimes hard to grasp the most salient plot developments. Greater contrast of pacing and volume would help, but you don’t need to grasp all the details of political intrigue to appreciation the drama of this dysfunctional family.

There are no nice people in this show, yet they are all endearingly familiar. As described by each other, Henry is a gleeful “master bastard and failure as a father” married to a “dishonest and inhuman” beauty who confesses to disliking all her children: Richard, the would-be “assassin,” Geoffrey, “a device x a stinker,” John, “a walking pustule,” and Eleanor’s “dangerous” protégée, Alais.

So why do we care what happens to any of them? Because Eleanor, whose misery and machinations feed this crusade to thwart Henry’s will, is the most sympathetic of the depraved lot.

This costume drama has an authentic feel whose magic is broken only twice: once when the playwright interjects omniscient voice, and once by bad make-up. Prince John’s acne scars on opening night looked like fluorescent clown spots. Otherwise, though, director Mickey Handwerger has done a remarkable job with a sparkling cast in which Wallace, Watko, Reynolds and Casey reign supreme.

It’s a twisted olde Yule at Chinon Castle, one that elicited a collective Wow! from the audience at intermission, and one I bet you’ll enjoy more than a jousting match, a game of Risk or even dinner at Medieval Times.

Playing thru January 30 at 8pm Th-Sa; 7:30pm Su @ Colonial Players, Annapolis. $20 w/discounts: 410-268-7373; www.cplayers.com.

Assistant director and design team lead: Heather Quinn. Set designer: Eric Lund. Lighting designer: Alex Banos. Costumer: Beth Terranova. Stage Manager: Herb Elkin.

Editor’s note: Reviewer Jane Elkin swears she’s too professional to let her review be affected by her relationship (wife) to stage manager Herb Elkin.

top

© COPYRIGHT 2010 by New Bay Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved.

See Singular Sensations and Thrilling Combinations at Colonial Players’ One-Act Festival

See Singular Sensations and Thrilling Combinations at Colonial Players’ One-Act Festival