| Johnnies Talk Their Way Out of College

Among the one million college seniors who graduate this month across America were 95 Annapolis Johnnies. Here's a bit of what they had to do to get out.

by Christopher Heagy

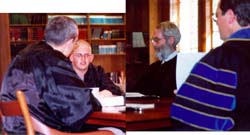

photo by Christopher Heagy

Andrew Kolb, at head of table, defends his interpretation of Fydor Dostoevsky’s Notes From the Underground in his senior oral examination at St. John’s College. Looking on and taking part are tutors John Verdi (far left), William Braithwaite (back to camera) and Radoslav Datchev.

When was the last time you had a conversation that delved into heavy thoughts?

When was the last time you read a book that made you think?

Maybe such experiences are reserved for the young and naive. Maybe we are too old, too cynical, too bombarded with stimuli from the cell phone, computer and television. Maybe our lives are moving too fast. Maybe we are working too hard.

And maybe Andrew Kolb and the other seniors of St. John's College will join us. But they haven't quite yet.

Top of the Heap: A Senior in Spring

Andrew Kolb - who wears his hair cropped short, the same length all over his head - is sitting with his face in a book, drinking coffee at Annapolis' City Dock Cafe.

When I lure him out of the book, he talks about his life. His high school years in rural Blacksburg, Virginia his philosophy-professor father how his father became a tutor at St. John's how bad a job washing dishes is and how touristy he thinks Annapolis is. He talks about how he's been offered a job to teach English in China but isn't sold on it. He thinks they only want to hire him because he's white and it's prestigious to have white English teachers.

On the other hand, he says, "I think it seems like a way to spend a year and not make a commitment and still do something that's not wasting time."

Kolb talks like any college senior as graduation nears. He talks in an easy way. The educational mountain is scaled, the summit is in sight. It's spring time and, even if you aren't sure what you're going to do, the world is blooming with opportunity. For a little longer, you're still in a world where your life is defined.

"In a lot of ways, I'm sorry to go," Kolb says. My life here is damn near perfect. I read books, I drink beer, I talk to my friends."

Four years after he left Blacksburg, Kolb still remembers the friends who questioned his decision not to focus on math or engineering or to get a degree he could make some money with.

"Coming here, my friends thought I was nuts. They said read books on your own, you'll never make any money. But the idea of going to school for professional reasons seemed like a waste of time to me. St. John's sounded appealing. You didn't have to sit in class and listen to lectures. You just read books and talked."

He believes he made the right decision.

"Since I've come to St. John's, I think I've gotten a lot more focus. Not in terms of finding a job, I'm still lost with things like that, but in terms of taking my life seriously and thinking about what I want to do thoroughly."

"I'll probably be poor," he jokes. "But I don't think I've wasted my time."

Facio Liberos Ex Liberis Libris Libraque

Education is America's key to success. The way one generation can move beyond the gains of the past.

Yet on its postage-stamp-size campus in the northwest corner of Annapolis, St. John's College teaches the past.

The St. John's curriculum is based on the works of the great thinkers, not just of our time but of all time. It starts in Greece with Homer and Sophocles, works its way through the ideas of the Roman Empire, through the Bible and Christianity, through the thinking of the Renaissance and Reformation before reaching the thinkers who built democracy.

Through those books, St. John's hopes to teach the skills of a "liberal arts education" - critical reading, independent thinking, organized writing, logical reasoning and confident speaking.

In 2001, St. John's still tries to live up to the motto established at the King George College in 1696: "We make free men from boys, books and a balance."

St. John's promises to make its graduates free; how to pay for the rest of life, they'll have to figure out on their own.

The Last Hill to Climb

In January, St. John's students returned from semester break, relaxed and full of Christmas cheer.

The seniors entered a time like none they have known in all their previous seven academic semesters. They returned to a month with no classes. But freedom comes with a price. At the end of the month an essay is due, and that essay must be completed and judged satisfactory if they are to graduate from this college.

Andrew Kolb began his final semester with an open and easy mind.

"It sounds great," he says. "You're 21. You have a month with no school. You don't have a job. Everybody goes in thinking 'I could work for an hour a day and spend the rest of the time drinking.' "

But as he set to work, dreams of carefree hours, days and weeks receded.

"I spent whole days sitting in my room, staring at the computer screen, thinking 'I've got to say something.'"

Johnnies can explore any work in the entire curriculum. Never before in their college career have they had such freedom.

"Our program is entirely required," explains St. John's dean Harvey Flaumenhaft. "The essay is a chance for a student to do sustained thinking about a subject."

On the subject of their choice, they have a month to read and re-read, write and re-write, think and re-think.

What if, when it's your chance to show what St. John's has taught you, the words don't come?

"This," says Kolb, "is a big thing."

Kolb Tackles Dostoevsky

Kolb decided to take on a dark, difficult book, Notes From the Underground, written by a degenerate Russian gambler, Fydor Dostoevsky.

Notes from the Underground, published in 1864, is a disturbing story of a bitter, petty, frustrated and inert man. "Underground man" takes pleasure in his isolated, self-destructive life.

"I read it for the first time the summer after my freshman year,"  says Kolb. I didn't think much about it; it's sort of an ugly book. It struck me at the end of my junior year, that it's really sort of a personal book. says Kolb. I didn't think much about it; it's sort of an ugly book. It struck me at the end of my junior year, that it's really sort of a personal book.

"He's talking right at you. People say that about a book they like, and that's why I like it. I thought the author was speaking to me. But this book, it feels like the author is insulting you.

"He's saying I'm bad, hideous, petty and small - and so are you.

"I thought this was something I would have to deal with at some point, if I have some of this 'underground man' in me," explained Kolb.

During the first two weeks, Kolb came up with the structure. The writing was free and easy. In week three, he hit a wall. He thought about turning in what he already had down.

During the final week, he decided to re-write about two-thirds of the essay

"In some ways the time's a curse," he says. "It's too much time. I know a lot of people who sat around and did it in the last three or four days. But I think the freedom gives you time to really mull over your own thoughts, to think about what is it you're really thinking."

Yes, Kolb decided by month's end, "I do have this person in me, this petty, cheap, suffering little man. But there has to be a way to deal with this. I know it sounds ridiculous to forgive a literary character, but that is what you must do because to forgive him is to forgive yourself.

"You've got to look at yourself and see the ways you've got this wickedness inside you and then not get caught up in it. That's the key: not to hate yourself because of it, to still find reasons to love yourself and find worth in life."

The Last Hill

On February 3, the essays were turned in. After a night of celebration, life on the St. John's campus went back to normal. The seniors returned to class.

With essay finished, the most difficult work was behind the graduating class. The senior oral still loomed, but there was time to take a deep breath.

A little time. Because next, each student must present his or her essay to a committee of three tutors. A committee that will ask questions. The oral combines a conversation, an exam and a defense.

"Standards for the oral are fairly loose," says John Verdi, chair of Andrew Kolb's oral committee. "It is a chancy kind of thing. You really can't prepare for it. But they do have to pass the oral to graduate, and there is the very remote possib ility that they might fail." ility that they might fail."

Each tutor on a committee gives the essay a quick read, judging it satisfactory or unsatisfactory. Unsatisfactory papers are returned for rewrites. Satisfactory essays, graded C– or higher, are scheduled for orals.

"The oral involves the other skill of talking on your feet and answering when confronted by three faculty members," explains Dean Flaumenhaft. "It pulls together what we hope the students have gotten out of our program."

With April 23, Kolb's oral date, looming on the horizon, he was still loose and confident.

"Sometimes the oral is a wonderful conversation," Kolb says. "Sometimes its awkward. It's something I'm not worried about. Orals before have always been one of my best experiences."

Kolb tells me he's heard that only one student in the last 14 years has failed the oral. In 26 years at St. John's campuses in Sante Fe and Annapolis, Verdi has never been on a committee where a student has failed an oral.

"I think what's riding on the oral has nothing to do with passing and failing," Verdi says. "This is something that they've heard about, that they've been going to and their friends will come to. It's a bigger deal socially and emotionally, I think, than academically."

Kolb's Hour

photo by Harvey and Harvey Photographers

At 3:45pm on April 23, tutors John Verdi and William Braithwaite enter the King William room. Following, Andrew Kolb is presented by the final tutor, Radoslav Datchev.

Imagine you're 21. You walk into a room to face three men 20 to 30 years older than you. You have spent a month writing a paper, pouring over a text, thinking and rethinking. Now, in front of your friends, these tutors will dig into your ideas, your words, your work. All you can do is think on your feet.

"Just walking into the room was intense," Kolb recalled a week after his oral. "I didn't feel that nervous. When I got in there and I was reading my summary, I realized my hands were shaking. I had to put the paper down on the table."

There is no doubt that Andrew Kolb is nervous when he walks into the King William room. His foot bounces on the floor. He sips water out of the plastic cup. He rephrases questions, looking for time to think. In the beginning, his oral drags.

"The situation in a lot of ways was very emotional. I was sitting there with three tutors, all whom have studied the book longer than I have. They're older, they have academic reputations that I've heard of. They've never heard of me. I'm definitely the small fry.

"I'm trying to express my thoughts in a way that answers their questions, and some of the questions were definitely leading in a direction opposite to what I thought about the book and what the paper said. There were times when I snapped answers out, when I was agitated."

But slowly, Kolb gets his intellectual feet. He starts taking the questions, the criticisms, he starts answering, he starts disagreeing, and in the last 20 minutes a hard-fought conversation builds.

Most of the friction is between Kolb and Datchev. They seem to have different interpretations of the book. By the end of the hour, Kolb is gripping the table, responding quickly, not backing down from his stance.

Kolb will later describe this oral as a "brawl in a very pleasant way."

The clock in the distance rings again: 4:45pm. Kolb thinks, "Oh, wow, it's over. That was much easier than I thought it would be."

The procession of robes leaves the room. The spectators stand and stretch.

In the robing room, Kolb takes off his gown. Anxious to leave, he shakes the tutors' hands. The tutors stay behind. They will decide on a grade for the paper.

Andrew Kolb races down the steps of the Barr-Buchanan Center. He pushes the door open and runs toward a group of friends.

"Man, you did well. Datchev was off the hook," one says. They stand for a minute and talk about the oral before Kolb hustles off. At 5pm, a friend is on the hot seat.

That Was Then

A week after his oral, Andrew Kolb is at City Dock Cafe, reminiscing over his essay and oral, thinking again about the heated conversation.

"I found out that I had unwittingly taken the exact opposite stance on the book that Datchev has on Notes for the Underground," Kolb says. "In the robing room, I asked him afterward point blank 'were you baiting me, or do you really think that?' to which he gave me a really cryptic response: 'You don't understand. I'm from that part of the world.' I thought that was funny.

"I still wanted to meet with him and get him to lay it out for me and tell me what he actually thought of the book. We had a brief, friendly conversation on campus yesterday and agreed to meet next week."

For the last required time, Kolb has read a book that made him think, then shared his heavy thoughts in conversation. Now he and the other seniors of St. John's College are on their own to find where freedom takes them.

This Is Now

On May 13, Andrew Kolb earned his Bachelor of Arts degree from St. John's College. He walked on stage a student and left a graduate. After working the summer in Annapolis, he may spend some time in New York, maybe ride a train across Europe. At some point, he might find his way to China.

But now and for the next two weeks, Kolb is a senior in spring. He drinks beer, talks to his friends and enjoys thinking about all the reading he has done. For a few weeks he will just enjoy these moments.

What a beautiful time of year it is!

Copyright 2001

Bay Weekly

|