In Season: Tundra Swans

In Season: Tundra Swans

by Gary Pendleton

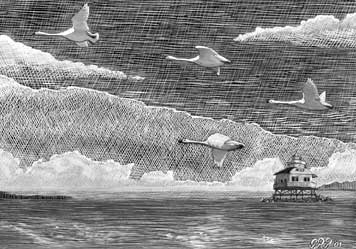

A sign of winter coming: a flock of tundra swans, four or five of them, flying flat out, their long necks reaching out to the next county, wings flashing brilliant white. As signs go, the arrival of migrating waterfowl is a more reliable indicator of season than the thermometer, for instance. Especially this year.

When honey bees buzz and forsythia bloom, what kind of December can this be? Then again, who knows? By the time these words go to print, we may have snow on the ground.

Tundra swans have arrived. I have seen them with my own eyes. The air may have been Indian Summer warm, but the Christmas decorations were up and swans were on the wing. So it must be that time of year. Soon, we hope, very soon, rafts of waterfowl will be visible on the Bay. I have heard the hunters’ guns go off early in the morning. So maybe they are already out there, beyond where I can see without getting out the binoculars.

Tundra swans are native North American birds that grace our region only in the winter. They are not too hard to distinguish from their cousins, the mute swans, which are European imports. Tundra swans have slender black bills, and their necks, when not in flight, are held up straight and high. Mute swans generally travel in pairs as opposed to groups of four or five. Their bulbous bills are black and orange, and their thick necks are often held in a graceful curve. Although beautiful, mute swans are considered to have a destructive impact on aquatic vegetation, which harms the entire estuarine ecosystem.

Tundra swans carry no negative environmental baggage. They can be appreciated on multiple levels: for the complexity of their migrations and natural history; for their beauty and elegance; and as symbols of Chesapeake Bay in winter.