Edgewater’s Stan Norris Chronicles the Weapon that Changed the World

Edgewater’s Stan Norris Chronicles the Weapon that Changed the World

56 years ago on June 6, D-Day turned the tide on the war in Europe. The war with Japan bloodied the world for two more years — until Leslie Groves got his job done.

Authors dream of publishing their books at the right moment in history. If Stan Norris, of Edgewater, misses the boat with his book on the Bomb it won’t be because India and Pakistan — and possibly terrorists — aren’t helping him. The brinkmanship in South Asia alone makes today one of the “three or four most dangerous times” in the nuclear era, according to Chesapeake Country’s historian of the Bomb, its making and its consequences.

The scariest nuclear moment, said Norris, was the Cuban missile crisis. “In 1962, it was highly dangerous, a close call that sent a strong warning signal that we had better be careful and do things to prevent a recurrence.”

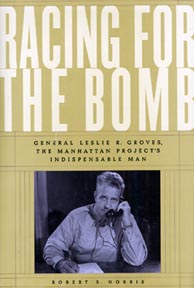

So far Robert Standish Norris’ timeliness has been only close enough to earn national praise in the Washington Post and elsewhere for Racing for the Bomb, his huge and scholarly but riveting biography of the man who marshaled the brainpower and the energy for the Manhattan Project. In the movie Fat Man and Little Boy, a dramatization of the race for the Bomb, that man, Col. Leslie Groves was played by Paul Newman.

Groves was an Army Corps of Engineers officer given the daunting assignment of building the atomic bombs that would be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. (He had just finished building the Pentagon.) The fact that he pushed for bombing an even more populous Japanese city, Kyoto, tells a lot about Groves, an obsessive, intensely patriotic, take-charge guy who marshaled the talent to do what no one had done before.

Norris, 58, is a nuclear weapons expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the nation’s most powerful environmental advocacy groups.

The history of his book is as compelling as its subject. Norris took over writing Racing for the Bomb after his friend Stan Goldberg died unexpectedly in 1996. Travels to Annapolis to interview retired military officers lured Norris and his wife, Myriam, to Chesapeake Country. The couple and their eight-month old Chessie, Zoe, live in an idyllic setting along Beard’s Creek.

Norris talked about his new book recently with Bay Weekly editor Sandra Martin and co-founder Bill Lambrecht.

Q Why’d you write such a big book? It nearly collapsed our bedside table.

Q Why’d you write such a big book? It nearly collapsed our bedside table.

A I have a colleague who says that big themes and big personalities need big books to do them justice. Still, it did get a little long and still didn’t say all I meant to say.

Q Why should people make time this summer to read Racing for the Bomb?

A A couple of reasons. Leslie Groves is a forgotten figure in an important story, building the atomic bomb. The things that he did to develop and test and use the Bomb had a profound effect on all of us in the decades that came afterwards.

Q Unless you’re at least in your 60s, you don’t have vivid memories of World War II, let alone Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Can you give our younger readers a sense of how the bomb changed our existence?

A I can’t think of anything else equal to World War II in changing all that came after. The Bomb not only ended the Pacific war but also ushered in a new era that we’re still wrestling with in terms of controlling humankind’s ability to destroy itself and prevent the Bomb’s use by other nations or, now, even terrorist groups that could set off nuclear devices in our cities.

Q Tell us about your friend Stan Goldberg, who started the book.

A He was a historian of science and a D.C.-based independent writer who, in the mid-to-late ’80s decided it would be a good idea to do a biography of Gen. Groves. He started going to libraries, archives and doing interviews.

In ’96, he got a rare disease and suddenly died. I went to his family, saying that the project needs to keep going, and I want to do it. They gave me all of his files. He hadn’t gotten to writing anything more than a couple of articles. He saved me two years of travel and work.

Q You describe Gen. Groves as a corpulent, commanding presence. Is it one of your conclusions that without him, the Bomb wouldn’t have been completed when it was?

A Absolutely. It wouldn’t have been ready when it was in 1945, and every one of those days was incredibly significant as far as creating the post-war world.

|

| The crew of the Enola Gay dropped the bomb. |

Q So was it a good thing that the Bomb was finished when it was?

A If it had not been done for another few months, there was an invasion of Japan planned with forces larger than D-Day. If the war had not ended when it did, the Soviet Union would have entered the War in the Pacific in a larger way, and we might have ended up with dual occupation of Japan. In terms of saving American lives, whether it was 500, 5,000 or 50,000, many more would have died in continued fighting had the bomb not ended it.

Q Could a terrorist today construct an atomic weapon?

A Not from scratch. The Manhattan Project shows the scale that goes into it. After we had the bomb, then came the Soviet Union, Britain, France, China, Israel, India and Pakistan, and each required a sizable commitment of manpower and resources. I don’t believe that Al Qaeda’s doing this is in the cards.”

Q What is the so-called “dirty bomb” that we are told we must fear in this era of terrorism?

A It’s not a nuclear explosion but a conventional explosion blowing around something radioactive — radium, cesium, plutonium. Probably not many people would be killed, but it could make an area radioactive for quite some time.

Q Is a “suitcase bomb” a realistic threat here for a terrorist?

A There’s no chance of them building one, but they might be able to steal one, perhaps from the Russians.

Q Traveling in New Delhi a few years ago, I had a frightening premonition that this region would be the first place in 60 years where a nuclear weapon would explode.

A You could be right. That region is by far the most dangerous place. India and Pakistan have had three wars already and both have arsenals of dozens of nukes. Right now, there are one million soldiers on the border: 700,000 Indians and 250,000 Pakistanis. Each takes a little step to be more prepared, and that causes the other to be nervous, and they tumble into conflict. When each side fears the other will use nukes, each could go first.

Q Having let this genie out of the bottle, wouldn’t we be better off if we could stuff it back in?

A That assumes we could. We just have to figure out a way to keep it from being used. There are similar boundaries in terms of biogenetics today. The question is, how are you to stop human beings from setting off their Bombs.

QBiographers get to know their subject intimately and sometimes, as with Robert Caro and Lyndon Johnson, they don’t like the people they write about. Did you like Gen. Groves? Did you think him a good man?

A Yes, basically, in the end. He was as honest as the day is long and very patriotic. He certainly loved his family and his country. He was a tough customer in terms of being brusque and rough, and he bruised a lot of people. But this all was in the service of getting the job done. We need people like this from time to time, and we have a society that produces them.

Q On the morning of August 6, 1945, his family was quite surprised when they learned what Groves had been up to for the previous 1,000 days.

A Yes, his wife and two children did not know what he had been doing for the past three years, which was testimony to the biggest secret of the war.

Scientists often criticized him for being too secretive and compartmentalizing knowledge. His basic rule was that everyone should stick to their knitting. He relaxed that when he had to, but the basic thing he did with scientists was put them all together at Los Alamos and put a fence around them and let them interact within that fence.

Q Groves was part of the Army Corps of Engineers, which these days is reviled in some quarters for its environmentally destructive and even scandalous practices. Was the Corps once a respected agency?

A In the ’20s and ’30s, they were an honorable force. Those guys really held themselves to very high standards. Today, they are held almost in contempt for the things they have done to try to alter nature.

Q Did you write a lot of your book here in Chesapeake Country?

A We moved here three years ago, and it took almost five years to write. A lot of it was done in this very pleasant atmosphere on Beard’s Creek.

Q Do you have another book planned.

A I’m not ready. It’s been five years and takes up all the free time.