|

My right leg dangles out of the hammock so my toe can give the gentle nudges that keep us swaying. Snuggled up against me is my eight-year-old daughter, Emily, listening as we read a book over the emerging night noises. A chorus of frog song fills the air, vying with the buzzing of cicadas and other insects. Emily’s younger brother, Tommy, scampers over the lawn catching fireflies, then sets them free. He adds his laughter to the surrounding sounds.

Above, the sky deepens to the dark blue of dusk. The sun has just set, but its light and heat remain. Summer humidity presses in upon us. I feel a drop of sweat slither down the back of my neck. We are waiting.

As I read, Emily periodically scans the sky above. The silver of a jet reflecting the fading rays of the sun glides across our view, leaving a wispy contrail behind. A few purple martins dash about well above the treetops, surrendering the sky as the darkness gathers. Then we see what we have been waiting for.

|

Bats in Maryland

|

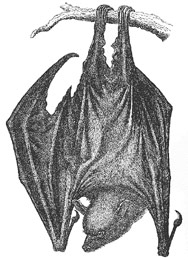

Little brown bat

Northern long-eared bat

Indiana bat

Eastern small-footed bat

Silver-haired bat

Eastern pipistrelle bat

Big brown bat

Red bat

Hoary bat

Evening bat

|

|

|

|

|

“There’s one!” shouts Emily as she points to the bat fluttering against the now nearly steel-gray sky. The bat swoops before disappearing. Tommy rushes over to join us in the hammock. The book rests forgotten on my chest.

The bat returns a minute later, this time accompanied by another. Both bats flutter erratically above us, rapidly changing directions. A third joins them. They zip this way and then zoom that way. Because of their stockier silhouettes and the unpredictable flight patterns, the bats cannot be mistaken for the sleek, recently departed purple martins.

“Great! Look at how many bugs they are eating. Bet they’re catching plenty of mosquitoes tonight,” exclaims Emily. My children and I lie on our backs, fascinated by the aerial show above us until it becomes too dark to see.

The creature that zips through Halloween legendry bears little resemblance to bats that fascinated my family on warm summer nights.

Bat Rap

In our family, bats are not the villains they’re often made out to be. Fear of bats is primal, some psychologists believe, like the natural revulsion many people have to spiders, snakes and mice. Interesting. Don’t all these animals make appearances in Halloween legendry?

I’d like to be able to feel superior because I have no fear of bats, snakes or mice. But no one is perfect. A spider elicits my scream almost every time.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, fed the human fear of bats, doing the creatures no favors. A host of vampire horror films perpetuated the myth, as did the popular 1960s’ soap opera, Dark Shadow.

All this bad rap translates into abundant misconception. One pert, well-educated coworker got quite agitated when I told her of our bat-watching routine. A horrified look froze her face, and her hands flew to her coifed head as she exclaimed, “Oh! Aren’t you afraid they’ll get tangled in your hair?”

Bats are also reviled as flying mice, blind and a likely source of rabies.

Perhaps opinion would be different if we learned what fantastic creatures bats are and how they benefit us humans.

No Blind Mice No Blind Mice

First, bats and mice are not closely related. In fact, bats are more closely related to humans than to mice. Disturbing, no doubt, to the people who fear them.

One of the most fascinating things about bats is their ability to navigate. They are far from being “blind as a bat.” No bats have poor eyesight, while some (such as fruit-eating bats) possess eyesight far better than ours, especially at night. About 70 percent of the world’s bats (including all that live in Chesapeake Country) also echolocate.

Animals that echolocate make high-pitched sound pulses through their noses or mouths and listen for the echoes returning from the surrounding environment. Just as dolphins and whales echolocate in the ocean, bats do it in the air. Bats can determine an object’s shape, size, distance and even texture by these echoes.

“A bat’s ability to echolocate is so acute that it can detect objects as small as the width of a human hair,” says Andy Brown, senior naturalist at Battle Creek Cypress Swamp Sanctuary.

Maryland Department of Natural Resources bat expert Dana Limpert seconds Brown’s observation, drawing on her experience at an old iron mine during a bat swarm. “I was standing right in front of the mine as over 500 bats rushed past and swirled about me,” she said. “A bat swarm appears chaotic, but it isn’t. There is definitely some sort of organization to it. The bats came pouring out of the opening right past my face. Not a single bat hit me. Not one got in my hair. No bats hit each other. They have such amazing navigation skills!”

If a swarm of hundreds of bats could so easily avoid Limpert, even the most bat-paranoid among us need not fear that a lone bat will get tangled in our hair.

Blood and Empathy

Bats, like all mammals, can transmit rabies, but the incidence of bat-to-human transmission is very low. Dog attacks and lightning strikes take more lives.

In the last half century, only 40 people have died in the United States as the result of contracting rabies from a bat. The most recent Maryland death occurred in 1976. The victims had not been attacked by rabid bats. Instead, the humans were infected when they ignorantly picked up a sick bat with their bare hands; the bat bit them in self-defense.

Skunks, raccoons and foxes are rated higher as rabies carriers by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Yet these animals don’t suffer the poor reputation of the bat. In fact, many consider the raccoon an appealing creature. Skunks, raccoons and foxes are rated higher as rabies carriers by the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Yet these animals don’t suffer the poor reputation of the bat. In fact, many consider the raccoon an appealing creature.

Vampire legends are, of course, nonsense. Vampire bats don’t even exist in the region of Transylvania in Europe where Stoker set the tale of Dracula. Rest easy. They don’t live in Chesapeake Country either.

Vampire bats live in Central and South America. They do feed on blood, though it is far more likely that they extract it from livestock than humans. Vampires normally bite their victims on the body or an extremity, rarely in the neck. The bats also don’t suck the blood; they lap it as it oozes from the wound.

You may think a diet of blood implies a grisly personality. Nothing could be further from the truth. Vampire bats display unusual social empathy. If a baby in the colony is orphaned (a death sentence in most animal societies) an adult adopts it. Scientists have also observed vampire bats sharing food with other less advantaged members of the group. Vampires are not the heinous villains they are made out to be.

Home Sweet Home

Who are the local bats my family observes wheeling above us on oppressive summer nights? What are they like?

Not much is known about our local bats. Studying bats is difficult, naturalists say. It requires a technique called mist netting, which entails hanging nets to ensnare the bats in flight, rather like stretching a net across a stream to catch trout. The mesh must be extremely fine to remain invisible to the bats’ keen echolocation.

“Bats are secretive. Studying them is a challenge,” says Natural Resources’ Limpert. “Bats are secretive. Studying them is a challenge,” says Natural Resources’ Limpert.

One of the biggest challenges is the miniature equipment scientists must use. The bats’ size requires researchers to fit them with tiny tracking devices powered by even tinier batteries with very short lives. As a result, researchers can only track bats briefly. So much about these creatures remains unknown.

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources lists 10 species of bats as living in or migrating through Maryland. All are small. The biggest is the hoary bat. Its wingspan may seem large at 13 to 16 inches, but the animal weighs no more than an ounce. The world’s largest bat, the giant flying foxes of Indonesia, dwarf our local species with their wingspans of almost six feet. Our smallest inhabitant, the eastern pipistrelle, weighs less than one-fifth of an ounce yet has a wingspan of eight to ten inches.

Bats are particular about where they live. Local bat populations, explains Limpert, tend to congregate near river areas, often within a quarter-mile of a freshwater source. Rivers supply the bats with drinking water, but they also provide a rich hunting ground for a variety of insects. According to Limpert, bats even use rivers as flight corridors.

|

Library Resources to Engage Your Kids

|

Animals Among Us: Living with Suburban Wildlife

by Fran Hodgkins

Bats by Gail Gibbons

Bat Loves the Night

by Nicola Davies

Kids Discover Bats (video)

by Linda Litowsky

Little Bat’s Halloween Story

by Diane Mayr

Stellaluna by Janell Cannon

|

|

|

|

|

Bats prefer hot, dry places for daytime summer roosting. Depending on the species, roosts could be under a large leaf, the tiny space under loose bark or the corner of a barn or attic. Bats even roost under shutters.

Bat boxes do not always attract bats. If you want bats, you may have to experiment, moving bat boxes around before satisfying the picky tastes and temperature requirements of bats.

Males often remain solitary in summer, only roosting in large groups when they hibernate. Females, however, form nursery colonies where they give birth to their pups. For the first one or two weeks, the pups cling to their hunting mothers. Then, the mothers leave the young together in the nurseries at night, coming back periodically to rest and nurse.

Limpert says the largest colony on record in Maryland was one of more than 9,000 in Cecil County, but most colonies are much smaller. An average colony has about 50 members. Any colony exceeding 100 in Chesapeake Country is considered large.

Bats come into conflict with people when they find a way inside a house. Older buildings tend to be easier for bats to access, but some newer homes can harbor bats. Many people evict the bats as soon as they discover them. But not all.

Limpert relates the story of an Annapolitan who owned an older home she knew had bats in the attic. She didn’t mind them, and when she had to replace the roof she worried what would happen to her bats when construction began. She and Limpert determined the best location for a bat box. When work started, the bats moved into the box. “The woman even painted the bat box to match her shutters,” said Limper.

Bat Seasons

No one really knows where our local bats go when winter arrives. Most bat species hibernate in caves and mines, though a few species — like the red bat — will also hibernate in tree cavities or — like the big brown bat — in buildings. Places where bats roost during winter are called hibernacula.

There are no caves or mines in Chesapeake Country. Most of our bats must migrate somewhere. But where? There are caves and mines in West Virginia and western Maryland. There are also suitable locations in Pennsylvania, Virginia and New York. Experts know bats hibernate there. They even know that the same species that live in Chesapeake Country hibernate in these caves and mines. But they still don’t know from which regions these bats come. They cannot track bats long enough to determine their migration routes. So migration is another of the many bat mysteries.

The time of year when bats live in Chesapeake Country depends on the weather, specifically the temperature. The temperature must be warm enough to support insects. No insects, no bats. Most years, bats frequent our area from April to early October. However, a warm spring can entice bats to come as soon as March, and a toasty Indian summer can keep them here through November. The time of year when bats live in Chesapeake Country depends on the weather, specifically the temperature. The temperature must be warm enough to support insects. No insects, no bats. Most years, bats frequent our area from April to early October. However, a warm spring can entice bats to come as soon as March, and a toasty Indian summer can keep them here through November.

I remember one mild October evening years ago. Families were setting up for our annual community Halloween party when a bat swooped through again and again. Children shrieked with delight. For most, it was their first bat sighting. Still, few neighborhood parents indulge themselves and their kids in my brand of summer evening entertainment. Long before Emily and Tommy shared the hammock with me, my older boys, Christian and Derek, were my bat-watching companions.

Bat Take a Bow

Andy Brown gets animated when he describes how a bat feeds. “They are so perfectly adapted for what they do,” he says. “Sometimes a bat grabs a moth on the wing, but more often it uses its entire body. Maybe it uses a wing tip or even its tail to sort of scoop a moth toward its mouth.” Brown hunches over, his arms curved in wide arcs in front of him like wings to demonstrate. “The bat becomes sort of like a big catcher’s mitt.”

All our local bats eat insects. Lots and lots of insects.

“Bats fill a very important role in nature. They and spiders are the only nighttime insect feeders,” says Limpert, “and bats eat a tremendous amount of insects.” A single little brown bat can eat more than 1,000 mosquito-sized insects in an hour. Bats eat far more insects than do spiders. When was the last time you noticed a spider web with 1,000 insects caught in it?

What’s more, bats eat the bugs that bug you. “Bats eat many insects that are agricultural and garden pests,” says Limpert. A colony of 150 big brown bats eats about 33 million (yes, million) root worms each summer, providing substantial protection for farm crops. If you hate mosquitoes and love local produce, you might see bats in a new way. What’s more, bats eat the bugs that bug you. “Bats eat many insects that are agricultural and garden pests,” says Limpert. A colony of 150 big brown bats eats about 33 million (yes, million) root worms each summer, providing substantial protection for farm crops. If you hate mosquitoes and love local produce, you might see bats in a new way.

Bats living outside Chesapeake Country help us, too.

Do you like bananas? You can thank nectar-eating bats in Central and South America. In the wild, important agricultural plants such as bananas, mangoes, cashews, dates and figs depend on bats for pollination and seed dispersal.

Even the much-maligned vampire bat may soon contribute directly to humans. Its saliva contains a chemical that stops blood from clotting. Drug companies are trying to manufacture a medicine based on this chemical to prevent heart attacks and strokes.

Bats pose no threat to humans and are beneficial. Instead of fearing this creature, we should applaud it.

Bats in Trouble

Environmental groups believe numbers of bats are declining worldwide, even though studies of bat populations are too incomplete to provide data to support this theory.

Like all wild animals, bats face the loss of their habitat as they get squeezed by the growing human population. But bats face another problem: Bats are killed just for being bats. Humans persecute them out of fear and ignorance.

Bats also suffer from another human impact called “pesticide loading.” Just as birds of prey suffered from DDT in the 1950s and 1960s, creatures at the top of the food chain — like bats — are most vulnerable to pesticide loading. When a bat eats large numbers of insects laden with pesticides, the pesticide concentrates in the bat’s fat stores. Bats depend on their fat to sustain them during months of hibernation. The slightest disruption to these reserves mean life or death for a bat.

Up Close and Personal Up Close and Personal

Warming up to bats? Want to see one for yourself? You’ll have to wait until next spring or summer to see a local bat, but you can look at plenty of bats if you take a short drive to the National Zoo. The bat cave in the Mann Building (near the great cats) is a family favorite.

We step in from the bright sunshine and plummet into darkness. With a quick intake of breath Tommy, normally a bold little boy, reaches his hand up, slipping it into mine. I grab Emily’s. This is a great spot to lose a child.

We pause to let our eyes adjust. Gradually, we see the dim light of the exhibit and shuffle toward it. Other visitors appear as indistinct shadows beside us. The darkness and low ceiling give the illusion of an actual cave, but thick glass separates viewers from the bats. Good thing. I understand the stench of bat guano is overpowering.

Minimal lighting illuminates hundreds of bats fluttering about. National Zoo curator Belinder Reser explains that the average bat population is about 450. Some bats eat the hanging fruit, some cluster upside down on the walls and others whirl through the cave. The atmosphere is eerie yet fascinating.

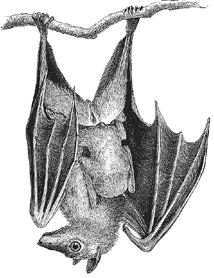

These bats are not local. They are fruit bats. According to Reser, insect-eating bats are too difficult to keep in captivity. The bats in the exhibit are a mix of short-tailed and Jamaican fruit bats, both species native to Central and South America and the Caribbean. They are small, similar in size to our local bats.

The exhibit provides excellent close-up views of the animals that are almost impossible for most people to see in the wild. When my family watches bats from our hammock, we content ourselves with observing silhouettes and erratic flight patterns. The bat cave, even in the low light, reveals more details and behaviors.

“Since the bats get sticky when they land on the fruit, they can often be seen grooming themselves,” Reser points out. Bats are fastidious animals. A very observant visitor might even glimpse a baby bat clinging to its mother’s chest. It’s easy to mistake that baby for just another bat because the pups are not much smaller than their mothers. The pups are 25 percent of their mother’s weight at birth and grow quickly. “Since the bats get sticky when they land on the fruit, they can often be seen grooming themselves,” Reser points out. Bats are fastidious animals. A very observant visitor might even glimpse a baby bat clinging to its mother’s chest. It’s easy to mistake that baby for just another bat because the pups are not much smaller than their mothers. The pups are 25 percent of their mother’s weight at birth and grow quickly.

My fast-growing pups leave the bat cave with reluctance.

Cool Bats

With Halloween upon us, my kids put up decorations, many of which are ominous looking bats. Fangs, fangs everywhere. Emily and Tommy know better than to be afraid. Bats are cool, not scary. As Emily tapes a particularly ghoulish vampire on the window, she smiles and asks, “Remember our bats? Will they be back next summer?”

|

Bat Rehabilitators

|

Chesapeake Country has two of only five state-licensed Master Wildlife Rehabilitators qualified to work with bats.

in Anne Arundel County, Davidsonville Wildlife Sanctuary: 410/798-0193

in Calvert County (Lusby), Orphaned Wildlife Rescue: 410/326-0937

|

|

|

|

|

They have returned for the 12 summers we have lived here. We believe we see the same threesome year after year. Bats have long life spans. The little brown bat is the longest-lived small mammal: It can live up to 32 years. I don’t know whether our evening visitors are little brown bats, but I think they’ll be back. I hope so. We would miss our aerial acrobats.

So would the farmers and you, too, now that you know how beneficial these small creatures are to us.

to the top

|

|