Commentary

When Big Species Return, We’ve Got to Live with Them

by Gary Pendleton

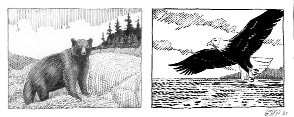

They are large and charismatic — and once so rare as to be virtually absent, extirpated, eliminated, extinct, gone — at least locally. They are among the most revered species of wildlife: the black bear and the bald eagle.

Loss of habitat caused the black bear to decline to the point of extreme rarity. Look to Garrett, Maryland’s westernmost county, to understand how changes in the land have affected bear populations. At the turn of the 20th century, it was nearly deforested.

Bald eagles and other large birds of prey were brought to near extinction by the pesticide DDT, now banned in the U.S. The pesticide accumulated in the bodies of prey animals, and over time DDT accumulated in the bodies of top predators, such as eagles.

Bald eagles and other large birds of prey were brought to near extinction by the pesticide DDT, now banned in the U.S. The pesticide accumulated in the bodies of prey animals, and over time DDT accumulated in the bodies of top predators, such as eagles.

Now, both populations are returning. In one case this news is cause for celebration. In another the good news is tempered with concern.

If watching eagles is your thing, go no farther than our tidewater. In eastern and even central Maryland, along the Bay and its tributaries, we have as many bald eagles as we did in the 1930s: over 300 breeding pairs, a threefold increase since 1990. Around the tidal marshes of the Patuxent River, near Jug Bay, eagles are seen almost daily. In other parts of the state they are even more common.

The bald eagles’ rise from the brink of extinction is one of the great success stories in wildlife conservation. Eagles are still a protected species, though they are no longer on the federal list of endangered species.

In the hills and hollows of Western Maryland, the black bear is also making a comeback from local extinction. The Allegheny Mountains that bisect western Maryland are the source of the growing number of bears in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia. An increase in the amount of high-quality bear habitat, including second-growth forests, in our Western counties, particularly Garrett, explains their growing presence in Maryland.

To count how many bear live west of Cumberland, Maryland Department of Natural Resources biologists devised a scheme combining such low-tech materials as molasses and barbed wire with high-tech DNA analysis and sophisticated computer programming. Molasses attracted bears to a bait station, but to reach the bait, the bears had to crawl under a strand of barbed wire that would snag hair. Scientists then used DNA analysis to identify individual bruins. Their best guess: 227 bears.

East of Cumberland, biologists estimated about 100 bears live.

The survey confirmed what farmers and citizens have been saying: bears are a nuisance.

Humans, it seems, have mixed feelings about bears. We love them, and we fear them. We like to see them, but we are afraid to have them too close. Whether your bear is a cute teddy or big baddie depends on how close it is or how often it makes an appearance. A bear can be a benign presence or an intolerable nuisance.

What is it about bears that engenders such complex emotional responses in humans? “We and they are, from an ecological standpoint, virtually indistinguishable from each other,” wrote William Ashworth in Bears, Their Life and Behavior. “Both of us are large, intelligent omnivores … Both of us like the same foods and we seek them in the same location.”

We compete for the same ecological niche, and the Gause Principle, a fundamental rule of ecology, says that two species can not occupy the same ecological niche. “Where bears and humans interact, one of us must always lose,” writes Ashworth.

If you accept the Gause Principle, the tension between bears and humans is inherent and ancient.

As the population of once-rare species such as bald eagle, black bear and white tailed deer (which spread Lyme disease), continue to rise, the ever increasing human population must deal with the consequences of living in close quarters with our neighbors. Management plans, scientific surveys and outreach programs help, but there is no one solution that works.

For many people, living near wildlife is not a problem but an amenity. In the presence of a black bear or bald eagle, most of us experience awe and wonder.

Considering how close we may have come to losing very important species such as the bald eagle, we will, with hope, view the challenge not as a burden, but rather a responsibility we gladly accept.

to the top