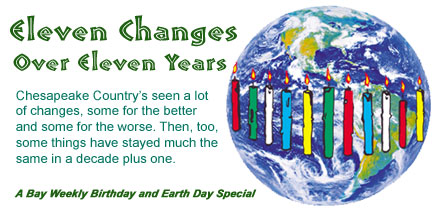

At age 11, you’re not old enough to vote, to drink liquor or to fight a war. At 11 years this week, Bay Weekly is old enough to measure the vital signs of Chesapeake Country.

There’s something satisfying to us about the number 11, beginning with its double ones. Eleven means you’ve not only reached a decade but are hurdling into the next one.

When we look back over 11 years, we see that the biggest stories remain the ones that led us into this Bay Weekly enterprise: environment: quality of life, culture and lore, people and places in Chesapeake County. That’s why Bay Weekly celebrates its birthday on Earth Day.

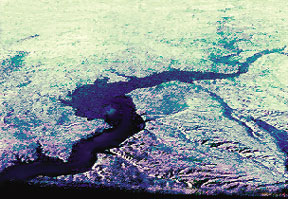

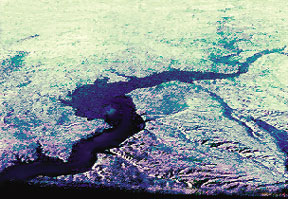

I. Chesapeake Bay’s Fortunes Ebb and Flow

Over the past 11 years, all but the last may go down in history as the decade we nearly talked Chesapeake Bay to death.

The constant stream of do-good reports — punctuated by pronouncements of disaster — may well have inured and confused you into tuning out. The bureaucracy created 20 years ago to restore the Bay continued to grind, but it seemed governed by the law of diminishing returns.

“By and large, the last 11 years have been dark days for Chesapeake Bay,” says Howard Ernst, the Naval Academy political science prof whose 2003 book, Chesapeake Bay Blues, helped break the spell of fruitless good intentions.

“We have seen oyster harvests fall to record lows, the crab population stressed to the point of collapse, toxic algae outbreaks, sediment plumes and a record dead zone,” Ernst told Bay Weekly. “Watermen abandoned their profession, and we saw the Bay and almost every one of its tributaries listed by the EPA as impaired bodies of water.”

Now, with all the damage reaching crisis proportions, the tide has turned. Maryland’s General Assembly approved Gov. Robert Ehrlich’s Flush Tax, providing the ingredients Ernst complained as lacking — political will and money — and mixing it with the science and technology developed these last 20 years.

Now, with all the damage reaching crisis proportions, the tide has turned. Maryland’s General Assembly approved Gov. Robert Ehrlich’s Flush Tax, providing the ingredients Ernst complained as lacking — political will and money — and mixing it with the science and technology developed these last 20 years.

The neatly nicknamed tax looks like the best hope in these new Bay times for bringing back clean water. Clean water, explains Chesapeake Bay Commission’s Ann Swanson, “is to our Bay very like the ballfield in field of dreams. If you restore that water, living resources will come.”

The tax will raise $60 million to fund technology upgrades, enabling Maryland’s 60 biggest sewage treatment plants to remove 97 percent of nitrogen from the water they pump back into the Bay and its tributaries.

“I’ve worked on Chesapeake Bay legislation for 20 years, and there is nothing that has accomplished this level of pollution control in that period,” Swanson says.

Achieving all that will cost Marylanders $30 per household each year — about the cost of a family night out at the movies.

Of course, just as one night at the movies is never enough, neither is just upgrading sewage treatment.

“Far more nutrient pollution comes from agriculture sources than sewage,” warns Ernst. “Unless all the Bay states adopt sensible agriculture rules, there is little hope for large-scale improvement.”

So there’s still more work to do on our field of dreams, and it mustn’t take another 11 years.

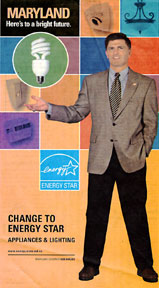

II. Maryland’s First Republican Governor in Three Decades

The last few years have been anything but politics as usual in traditionally Democratic Maryland.

Not since 1967–’69, when Spiro Agnew occupied the State House in Annapolis, had Marylanders elected a Republican governor. That we did in 2002, choosing Robert Ehrlich over Kathleen Kennedy Townsend.

In Ehrlich, Marylanders found an appealing brand of Republican less interested in party orthodoxy than his two-time predecessor, Ellen Sauerbrey. He was, in the estimation of political analyst Don Norris, “a good Republican, which would still be beaten by a good Democrat.” But either Townsend wasn’t good enough or voters were too disgruntled with eight years of her boss, Parris Glendening.

In Ehrlich, Marylanders found an appealing brand of Republican less interested in party orthodoxy than his two-time predecessor, Ellen Sauerbrey. He was, in the estimation of political analyst Don Norris, “a good Republican, which would still be beaten by a good Democrat.” But either Townsend wasn’t good enough or voters were too disgruntled with eight years of her boss, Parris Glendening.

Shifts in party registration may be eroding Maryland’s standing as a Democratic state. But party hasn’t made a difference in legislation coming out of Annapolis thus far, as the first big issue on the table — slot machine gambling — is more than a party-line matter.

One of the surprises thus far with Ehrlich is that his first significant piece of legislation is an environmental initiative as well as something most Republicans abhor, a tax increase — one that we heartily support. Deemed a “user fee” by Ehrlich, the new Flush Tax will generate $60 million to begin ridding the Chesapeake of damaging nitrogen pollution.

Progress on the Bay takes bipartisan support. “We needed a very fiscally conservative leader to make a recommendation like this,” said Chesapeake Bay Commission’s Ann Swanson. “Governor Ehrlich is that, and he is not known as a card-carrying environmentalist, so he was able to garner the interest of more conservative legislators along with the full cast of legislators known as environment leaders.”

Does such collaboration mean the two parties will live happily ever after? Don’t bet on it. That’s the advice of Norris, a professor at Maryland Institute for Policy Analysis and Research at University of Maryland Baltimore County.

“We’ll have the same, if not worse, budgetary problems next year,” says Norris. We’ve got a conservative governor who took the pledge on no new taxes and cannot back off on it. We’ve got a speaker not willing to give on slots without some movement on taxes. We’ve got a train wreck coming, with massive budget cuts that hurt everybody.”

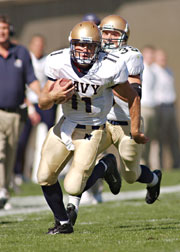

III. Sports Powerplay

Eleven years ago this week, Oriole Iron Man Cal Ripken was starting at third base, at the year-old Camden Yards, a year away from breaking Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,130 consecutive games.

The Ravens were called the Browns and resided in Cleveland.

The BaySox were a glimmer in Bowie’s eye, and Navy football was facing yet another losing season 4–7.

The Maryland Terrapins were a year away from making the first of 11 consecutive trips to the NCAA Tournament.

The Maryland Terrapins were a year away from making the first of 11 consecutive trips to the NCAA Tournament.

And the Redskins were coming off a 4-12 season, with a new coach in town ready to lead the team back to glory.

Some say sports are a metaphor for life, and if that’s true, Chesapeake Country sports fans have climbed to the peaks and mined the deepest chasms, depending on their allegiance.

Cal is gone. The only way to see him now is in the owner’s box up in Aberdeen or in TV commercials pitching products from chips to cable television.

The Cleveland Browns moved to Baltimore, became the Ravens and, in 2001, won the Super Bowl. Another local species, the Maryland Terrapins, brought an NCAA basketball championship home to College Park in 2002.

Navy suffered a few more years, but the Mids showed amazing resilience in 2003 by going 8–4 under coach Paul Johnson, doing to their opponents what they’ve done to Army four times in five years. This week Navy was awarded the coveted Commander In Chief Trophy, as the best of the nation’s three football-playing military academies.

The BaySox have continued to supply the revamped Orioles with young players hoping for baseball infamy.

And even though nothing’s changed with the Redskins’ play, they are now a Maryland team with a new state-of-the-art stadium in Lanham.

IV. Women Riding High in Anne Arundel Government

In 1987, Maryland’s Barbara Mikulski entered the United States Senate on nobody’s coattails, proving that the right woman could open any door — except, so far, to the White House.

Women have opened their own doors into the Maryland Senate and House of Delegates since 1922, the year after women won the right to vote — though not until the 1980s could women delegates open the door to their own rest room, a first achieved by Del. Pauline Menes [Bay Weekly Interview Vol. XII, No. 12: March 18].

Calvert County women have yet to open either Chamber door; in all its 350 years, Calvert has not sent a woman to the General Assembly.

Since Lucille Maurer took the job in 1987, women have watched over Maryland’s treasury, including the current treasurer, Nancy Kopp.

In city and county councils and boards of commissioners, women make news but they no longer are news.

What is news, however, is Anne Arundel’s election of women to its two most visible offices during Bay Weekly’s watch these past 11 years.

What is news, however, is Anne Arundel’s election of women to its two most visible offices during Bay Weekly’s watch these past 11 years.

Janet Owens made that news in 1998, winning election as county executive after achieving an earlier first of beating another woman, party newcomer Diane Evans, in the Democratic primary. In 2002, Owens stretched her record as the county’s first two-term woman county executive.

The county’s sole municipality, Annapolis, followed suit in 2001, electing its first woman mayor, Ellen Moyer — though not its first Mayor Moyer. Moyer’s ex-husband, Roger, known as ‘Pip,’ had been Mayor Moyer in his own time, from 1965 to 1973.

Has it made any difference, having Madame rather than Mister Mayor and Executive? Certainly not in the practice of politics. It’s as uncivil as ever, despite the druthers of both elected ladies. It’s also, depending on your party and point of view, as progressive or reactionary, efficient or inefficient, decisive or divisive.

But having these doors opened makes a certain difference at another level, for no longer are the talents of half the population shut out.

“I am so proud that we now have outstanding women serving at all levels of government, especially in Maryland,” said Mikulski. “Elected women know that every issue is a woman’s issue; that’s why we fight for the day-to-day needs of women and the long-range needs of our country, states and communities.”

V. Rockfish Recovery

V. Rockfish Recovery

In the midst of all the doom and gloom concerning Chesapeake Bay in the early 21st century, let us not overlook a few happenings that give us a ray of sunlight. Foremost as an example is our beloved rockfish, and to a lesser extent the shad.

Many among us today don’t appreciate the gradually rebounding Bay shad fishery; for more than 15 years we have had a moratorium in effect. But with rockfish, anyone familiar with the Bay is heartened by their surprising and spectacular comeback.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, both rockfish numbers and catches were in serious decline. But it wasn’t until the mid ’80s that a moratorium was declared hereabouts. Soon thereafter it became coastwide. There were fears among netters and hook ’n’ liners that never again in their lifetimes would they be fishing for rockfish.

But these fish fooled us. They responded to the protection afforded them, and in five years there were sufficient numbers that restrictive fishing could be resumed. Fisheries scientists and managers, being conservative by nature, have since been cautious and prudent in gradually relaxing regulations. Last Saturday we enjoyed a bonanza of catching for the second consecutive season’s opener.

In Chesapeake Bay — where at least 80 percent of the East Coast’s stripers are hatched — the moratorium faced much resistance. More than a few griped it wasn’t necessary. The fish were cyclical, they argued, and we were on the low end of the cycle. Others insisted there were near stable populations though more difficult to locate. Prior to the coastwide moratorium, from many came the argument we shouldn’t save fish by closing the season here so fishermen of other states could catch them.

In Chesapeake Bay — where at least 80 percent of the East Coast’s stripers are hatched — the moratorium faced much resistance. More than a few griped it wasn’t necessary. The fish were cyclical, they argued, and we were on the low end of the cycle. Others insisted there were near stable populations though more difficult to locate. Prior to the coastwide moratorium, from many came the argument we shouldn’t save fish by closing the season here so fishermen of other states could catch them.

We in Chesapeake Bay bit the bullet; today we have a great striper fishery. If anything is to be learned, methinks — whether it be rockfish, shad, crabs, oysters, clams or whatever — we should pay more attention to the advice of our trained professional mangers and scientists whose record with shad and rockfish proved they knew what they were talking about. Enough said …

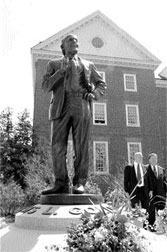

VI. A New Mr. Maryland

VI. A New Mr. Maryland

Politicians come and go, but comptrollers endure.

That’s one lesson we’ve learned in 11 years of watching Maryland politics.

Perhaps it has to do with the truth of the wise old adage that taxes are one of life’s two certainties. We all want someone we know and trust at the state’s cash register, and with no term limits, the job of Comptroller, collecting Maryland’s taxes and revenues, confers on its holder a permanence and a prominence in the public eye.

Back when New Bay Times was born on April 22, 1993, Louis Goldstein reigned as comptroller. Calvert County’s favorite son, Goldstein held the job for so long, 39 years in all, that we assumed him to be comptroller for life. Other state politicians run for office every four years. Mr. Maryland — who’d been winning elections since before World War II, starting with the General Assembly — ran for office every day, collecting public goodwill with his signature gold coins he passed out.

When death took Louis Goldstein on July 3, 1998, our Maryland universe seemed less certain. Not only had we lost Mr. Maryland, but comptroller had become simply a job. Who could fill Louie’s shoes?

William Donald Schaefer.

William Donald Schaefer.

Of course William Donald Schaefer wears nobody else’s shoes, for his style and size are unique.

When this weekly was born, Schaefer was governor; before that, Baltimore Mayor Schaefer; earlier still, Councilman Schaefer. As Bay Weekly turns 11, Comptroller Schaefer has won election and reelection. He’s stood by the river long enough to see the bodies of his enemies float by, but, like the able politician he is, he has also made new friends, including Gov. Robert Ehrlich, whom he joins on Maryland’s Board of Public Works overseeing the spending of the money he collects.

All may not be right with the world. But you know where you stand when the tax man is Mr. Maryland.

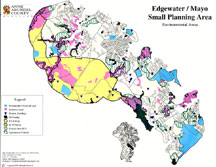

VII. Edgewater Explodes

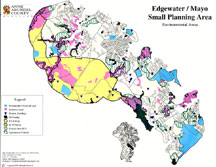

Until the early 1990s, Edgewater was a quiet village hugging the South River, which seemed an uncrossable barrier between the suburban sprawl to the north and the rural countryside down south.

Until developers discovered in Edgewater the same good land that had brought its first colonial settlers to London Town three hundred years earlier.

In the late 1990s, homes began to spring up off Route 2, followed soon by South River Colony, a golf-course community, which eventually expanded to the Villages of South River Colony with its town homes, retirement communities, shopping center, library, senior center, post office and, most recently, a new complex housing the Anne Arundel Southern District Police Station.

This year Main Street at South River, a retail shopping village on 8.6 acres, opened for business. A fire station is also coming.

Population has increased by about 12 percent over the decade, while the shopping centers draw in still more.

Population has increased by about 12 percent over the decade, while the shopping centers draw in still more.

As recently as 1999, citizens envisioned a smooth blending of the old and the new. The Edgewater/Mayo Small Area Plan sought to develop and preserve “the small town atmosphere of Edgewater where residents have access to nearby walkways, bike trails and services along or near the revitalized Mayo Road commercial village.”

Today some citizens appreciate just that blend.

Others hold Edgewater up as the worst thing that could happen to rural living, claiming it leads the long list of towns overrun by construction and outsiders longing for small town life but not willing to skimp on modern amenities.

Somewhere in between is 60-year-old Tom Bresnahan, a 30-year resident, who calls the changes “astounding.” He says he’s glad for the new dry cleaners, drugstores, restaurants and other businesses that keep locals from having to travel to Annapolis for everyday needs. On the other hand, he thinks Edgewater has gone too far.

“There’s just too much growth,” says the Giant food retiree. “You used to come to a red light and there were five cars in line, now there are 25.”

That’s the divide all our Chesapeake communities straddle.

VIII. Prime Time for Baltimore’s Mean Streets

Like all good stories, it started simply enough.

In 1987 Baltimore Sun reporter David Simon convinced both his newspaper and the Baltimore Police Department to allow him to follow homicide detectives. “Deal him out into the streets of Baltimore with more than its share of violence, filth and despair,” wrote Simon of the detective to appear in his book.

A year later — as Bay Weekly was still a twinkle in its creators’ eyes — Baltimore recorded 234 murders.

A year later — as Bay Weekly was still a twinkle in its creators’ eyes — Baltimore recorded 234 murders.

From Simon’s experiences on Baltimore’s mean streets came his first book, which was adapted to a television series; then came a second book; then another TV series and, somewhere along the line, a cultural phenomenon.

With the help of Baltimore movie-maker Barry Levinson, Simon’s book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets became the basis for the hit NBC television series that debuted in January of 1993, three months before Bay Weekly was born. At that time, Homicide was considered the “most reality-based police drama that ever aired on television,” according to TV Tome.

Coming on the heels of Steven Bochco’s Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue and Dick Wolf’s Law and Order, Simon’s Homicide helped spawn the hard-edge police stories taking over television. Together they set the genre’s standard: no-frills crime-solving and topical, clever cases.

Crime and punishment have long been subjects for writers, whether they be novelists, reporters or screenwriters, but Homicide brought it close to home by making the city of Baltimore its central character.

“It’s a city rife with conflict: race, class, you name it,” novelist Laura Lippman told Bay Weekly. Lippman sets her own Tess Monaghan mystery novels in Baltimore. “It’s also a city struggling to reconcile its past with a very different present and future.”

Simon followed up the success of Homicide with The Corner: A Year in the Life of An Inner-City Neighborhood, which he wrote with Edward Burns, a retired Baltimore City police detective. The true story of drug abuse on Baltimore’s east side, the book was turned into a series for HBO.

Simon followed up the success of Homicide with The Corner: A Year in the Life of An Inner-City Neighborhood, which he wrote with Edward Burns, a retired Baltimore City police detective. The true story of drug abuse on Baltimore’s east side, the book was turned into a series for HBO.

Simon also created HBO’s The Wire, another Baltimore based-crime drama that stretches taut the human dividing line between good and evil. Bay Weekly’s Matthew Pugh scored a bit part in the series and followed up with a story in our paper.

“I think the various Baltimore crime stories get the people right,” adds Lippman. “That’s because they’re produced by people who have a genuine affection for the city, people who live here and work here.”

Meanwhile, Chesapeake Bay is known through the television world as the better side of Baltimore, which in 2001 could brag that for the first time in a decade, the annual murder rated dropped below 300.

IX. Twin Beach Renaissance

In 1993, Bay Weekly wrote that North Beach had been down so long there was no way to go but up. “The town was punctuated by junked cars and dilapidated buildings, the streets were deteriorating, sidewalks were risky and trash accumulated in overgrown yards,” recalls Mayor Mark Frazer of the town he moved to in the mid-1990s. It got so bad that the town’s famous — and infamous — bars closed, though two churches remained.

Chesapeake Beach where, a century before, the boom began that birthed both towns, never fell so far. But from the playground of the mid-Bay — the early 20th century’s equivalent of Ocean City — the town had quieted down to a sleepy bedroom village with a million-dollar Bay view. There was still fun to be had at Rod ’n’ Reel’s restaurant and charter fishing fleet, Abner’s crab house, a marina, a few more bars and restaurants and a now-developed public beach. But the glamour had gone.

Eleven years later, the towns of North Beach and Chesapeake Beach are transformed, indeed rising so tall as to mimic the water-hugging high style of Ocean City.

In redefining themselves for a new century, the Twin Beaches have reclaimed their pasts. North Beach, the residential half of the partnership, has re-emerged as a real, walk-about town of 2,100 citizens with townhomes and condominiums joining the bungalows of an earlier era. The needs of residents at both ends of the age spectrum are satisfied with senior housing and center, at one end, and the boys and girls club at the other. People of all ages use both health and community centers.

In redefining themselves for a new century, the Twin Beaches have reclaimed their pasts. North Beach, the residential half of the partnership, has re-emerged as a real, walk-about town of 2,100 citizens with townhomes and condominiums joining the bungalows of an earlier era. The needs of residents at both ends of the age spectrum are satisfied with senior housing and center, at one end, and the boys and girls club at the other. People of all ages use both health and community centers.

Tall new buildings — four stories with up to 40 condos — close in on the beach, upsetting the scale. But the town has kept its long beachfront and public beach open and inviting, paralleling it with a landscaped boardwalk and a 500-foot fishing pier. North Beach provides a a fun day-trip destination by road and water for Baysiders everywhere. In the next year or so, a new hotel and conference center will make room for more overnight tourists, too.

In contrast to the North Beach of 11 years ago, the town today has, says Frazer, “a clean, attractive appearance that is going to make it a first-class destination for visitors while it remains an ideal small town in which to live.”

In Chesapeake Beach, housing villages — both waterfront and waterview and mostly upscale — have continued to sprout since the early 1980s, prettily drawing a new population that’s included senators and ambassadors, which gives the town a resort feel. Now there’s quite a crowd of new housing, with the biggest — a solid block of 71 units — rising on the waterfront.

The resurgent town made its biggest splash a decade ago with the opening of a turquoise-blue waterpark — and community center — right across the street from the Bay. Next, a boardwalk and rededication of Bayfront Park gave people new access to the Bay.

Another big splash came last month with the opening of the first hotel of Chesapeake Beach’s second century. Overlooking the water next to Rod ’n’ Reel, it booked its first full weekend for rockfish season opening.

“I love this town and what we’re doing,” says Mayor Gerald Donovan, whose family spans much of the town’s history. Donovan, with his brother and partner, also owns Rod ’n’ Reel and the new hotel. “When you walk through the hotel lobby and look at the pictures of the different eras — the train coming down from Seat Pleasant, a steamship docking at the mile-long pier, the amusement park over the water — you see it’s been a kind of renaissance.”

X. The Arts Flourish

Despite what our city cousins think, urbanites don’t own the arts. Art is like language; every culture makes its own. From native legends to carved decoys to Maryland’s signature glass blue crab to Nancy Hammond’s prints to weekly music jams at the Prince Frederick Fire Department to weekly newspapers — making art has never been Chesapeake Country’s problem.

The Arts thrive in our capital city. Colonial Players has been performing plays since 1949 and Annapolis Summer Garden Theatre since 1966. Annapolis Opera is 32, and the Annapolis Symphony Orchestra is 43. The Ballet Theatre of Maryland was born in 1979, and the Annapolis Chorale in 1973. And this year the place that brings them all together, Maryland Hall for the Creative Arts, celebrates its 25th anniversary, which is not coincidental with the birth of the Annapolis Arts Alliance.

“In the last decade, art interest has grown prodigiously in Annapolis and the whole county,” says Linnell Bowen, director of Maryland Hall. “We’ve doubled performances and exhibitions, and we’ve run out of classroom space. That’s a good sign. We should all be proud.”

On the popular music front, clubs come and go. But balancing the demise of Dick Gessner’s (long gone) and King of France Tavern (where a royalties imbroglio has meant no more music) has been Rams Head, whose On Stage features national acts as well as a few locals most nights of the year. A new venue on the jazz scene continuing the Charlie Byrd tradition is Powerhouse at the Loews Annapolis Hotel.

Locals, of course, make music on many other stages down- and around town, and you can follow the peregrinations of your favorites each week in 8 Days a Week in these pages.

Locals, of course, make music on many other stages down- and around town, and you can follow the peregrinations of your favorites each week in 8 Days a Week in these pages.

Galleries are just as peripatetic, but with every closing there seems to be at least one opening — though we’re still waiting to see who fills the void left by Nancy Hammond, whose gallery on State Circle opened, flourished and closed (Hammond retired to Internet sales) during Bay Weekly’s watch. Many shops and galleries showcase the work of Maryland artists, and you can find those and more on a walk downtown or a stroll through 8 Days a Week.

You can find arts in Southern Anne Arundel County, as well, with galleries in Galesville, Edgewater and even rural Lothian. And local musicians play at many of the restaurants, including Pirates Cove at Galesville and Calypso Bay in Deale.

For theatre-lovers, the two-year-old Bay Theatre Company provides the region an avant-garde change of pace. Dinner theatre, too, plays strong in Annapolis, where Sherry Anderson has sustained Chesapeake Music Hall as a long-running 52-week-a-year success, where other theatres failed before her. And, thanks to the Children’s Theatre of Annapolis, the stage is not just for grown-ups.

Anne Arundel Community College offers the range of arts, and at the north end of the county, three-year-old Chesapeake Arts Center is making a home, much as Maryland Hall does in Annapolis, for concerts, plays, dance and the visual arts.

Pasadena Theatre Company has roots up north as well, though it continues to take its plays on the road. To the west, two continually well-reviewed companies, 2nd Star Players and Bowie Community Theater, raise their curtains at White Marsh Park in Bowie.

In Calvert County, the arts are alive and well. For more than a decade, Solomons’ Calvert Marine Museum has drawn crowds with its big-name outdoor concerts each Memorial Day and Labor Day. In North Beach and Chesapeake Beach, music flourished through the 1950s, and now it’s back at Rod ’n’ Reel with performances by national acts. Rod ’n’ Reel also hosts occasional mystery dinner theater presented by itinerant Do or Die Players. The Beaches have their own theater company, too, in Twin Beach Players, and a dance company, Abigail Francisco School of Classical Ballet. Chesapeake Community Chorus is new, too, striving to give the arts voice.

In the visual arts, next month brings a new presence in the form of the artists’ cooperative and gallery ArtWorks @7th. With all these additions to their culture, Chesapeake and North Beach are towns in more ways than their new high-rise skylines.

Farther south, in Prince Frederick, the whimsical Main Street Gallery thrives, as it has since the 1980s. In Solomons, Carmen’s Gallery endures as the place for art.

Perhaps the greatest arts surpsise of all is in the tiny town of Dowell, where resides Annmarie Garden, dedicated in 1993. At this English-style garden, 30 acres host sculpture that includes modern conceptual pieces from Washington, D.C.,’s Hirshhorn collection.

XI. Bay Weekly Celebrates 11 Years

Eleven years ago, there was nothing like Bay Weekly. There were newspapers, there were magazines, and some were even free. But from the start, we set out to make this paper, born New Bay Times, different. We wanted it to be fresh and upbeat, relating to people’s lives and the way they lived them. But we also wanted a paper that stood for something, in our case sustainable living in a clean, beautiful environment.

It began around a fireplace on an early winter’s night in 1992 with the musings of Bill Lambrecht, Sandra Martin and Alex Knoll, who shared a dream of creating a Bay-oriented newspaper, that found interesting stories of Chesapeake Country, its people and places, its history and legends, its future and its needs. The paper would be free, to boot.

The idea germinated quickly. New Bay Times was born on Earth Day, Thursday, April 22, 1993. We printed 5,000 copies of that first issue, delivering them from Annapolis to Solomons to any business that would set them out for readers to take. That premier issue — chock-a-block full of stories but thin on ads and revenue — was a trial balloon: If people pick them up and read them, we said, then we’ll know we’ve struck a chord.

The idea germinated quickly. New Bay Times was born on Earth Day, Thursday, April 22, 1993. We printed 5,000 copies of that first issue, delivering them from Annapolis to Solomons to any business that would set them out for readers to take. That premier issue — chock-a-block full of stories but thin on ads and revenue — was a trial balloon: If people pick them up and read them, we said, then we’ll know we’ve struck a chord.

Less than a week later, all 5,000 papers were gone, and we printed another 5,000 to circulate until our second issue, scheduled two weeks after the first.

People liked the paper, and we kept it up, a new issue every two weeks, until, after our one-year anniversary, we made the leap to weekly. It’s been that way ever since, despite winter blizzards and summer hurricanes.

Looking back over 11 years, we see many changes. Gone are the all-nighters required to meet our printer’s deadline. Gone, too, is New Bay Times, grown and matured to Bay Weekly with the new millennium. Gone as well are people too many to count who’ve helped shape and create Bay Weekly over the years.

What will the next 11 years bring? We’re not much for crystal-ball gazing, but we can promise you this: more of the same, only better. We’ve promised to get this paper onto the streets and into your hands, every Thursday without fail. After 541 issues, we still hope you pick Bay Weekly up — and while you’re at it, pick up a copy for a friend or neighbor, too.

Bill Burton, J. Alex Knoll, Louis Llovio and Sandra Martin contributed to this story.

to the top

Now, with all the damage reaching crisis proportions, the tide has turned. Maryland’s General Assembly approved Gov. Robert Ehrlich’s Flush Tax, providing the ingredients Ernst complained as lacking — political will and money — and mixing it with the science and technology developed these last 20 years.

Now, with all the damage reaching crisis proportions, the tide has turned. Maryland’s General Assembly approved Gov. Robert Ehrlich’s Flush Tax, providing the ingredients Ernst complained as lacking — political will and money — and mixing it with the science and technology developed these last 20 years. In Ehrlich, Marylanders found an appealing brand of Republican less interested in party orthodoxy than his two-time predecessor, Ellen Sauerbrey. He was, in the estimation of political analyst Don Norris, “a good Republican, which would still be beaten by a good Democrat.” But either Townsend wasn’t good enough or voters were too disgruntled with eight years of her boss, Parris Glendening.

In Ehrlich, Marylanders found an appealing brand of Republican less interested in party orthodoxy than his two-time predecessor, Ellen Sauerbrey. He was, in the estimation of political analyst Don Norris, “a good Republican, which would still be beaten by a good Democrat.” But either Townsend wasn’t good enough or voters were too disgruntled with eight years of her boss, Parris Glendening. The Maryland Terrapins were a year away from making the first of 11 consecutive trips to the NCAA Tournament.

The Maryland Terrapins were a year away from making the first of 11 consecutive trips to the NCAA Tournament. What is news, however, is Anne Arundel’s election of women to its two most visible offices during Bay Weekly’s watch these past 11 years.

What is news, however, is Anne Arundel’s election of women to its two most visible offices during Bay Weekly’s watch these past 11 years. V. Rockfish Recovery

V. Rockfish Recovery In Chesapeake Bay — where at least 80 percent of the East Coast’s stripers are hatched — the moratorium faced much resistance. More than a few griped it wasn’t necessary. The fish were cyclical, they argued, and we were on the low end of the cycle. Others insisted there were near stable populations though more difficult to locate. Prior to the coastwide moratorium, from many came the argument we shouldn’t save fish by closing the season here so fishermen of other states could catch them.

In Chesapeake Bay — where at least 80 percent of the East Coast’s stripers are hatched — the moratorium faced much resistance. More than a few griped it wasn’t necessary. The fish were cyclical, they argued, and we were on the low end of the cycle. Others insisted there were near stable populations though more difficult to locate. Prior to the coastwide moratorium, from many came the argument we shouldn’t save fish by closing the season here so fishermen of other states could catch them. VI. A New Mr. Maryland

VI. A New Mr. Maryland William Donald Schaefer.

William Donald Schaefer. Population has increased by about 12 percent over the decade, while the shopping centers draw in still more.

Population has increased by about 12 percent over the decade, while the shopping centers draw in still more. A year later — as Bay Weekly was still a twinkle in its creators’ eyes — Baltimore recorded 234 murders.

A year later — as Bay Weekly was still a twinkle in its creators’ eyes — Baltimore recorded 234 murders.  Simon followed up the success of Homicide with The Corner: A Year in the Life of An Inner-City Neighborhood, which he wrote with Edward Burns, a retired Baltimore City police detective. The true story of drug abuse on Baltimore’s east side, the book was turned into a series for HBO.

Simon followed up the success of Homicide with The Corner: A Year in the Life of An Inner-City Neighborhood, which he wrote with Edward Burns, a retired Baltimore City police detective. The true story of drug abuse on Baltimore’s east side, the book was turned into a series for HBO. In redefining themselves for a new century, the Twin Beaches have reclaimed their pasts. North Beach, the residential half of the partnership, has re-emerged as a real, walk-about town of 2,100 citizens with townhomes and condominiums joining the bungalows of an earlier era. The needs of residents at both ends of the age spectrum are satisfied with senior housing and center, at one end, and the boys and girls club at the other. People of all ages use both health and community centers.

In redefining themselves for a new century, the Twin Beaches have reclaimed their pasts. North Beach, the residential half of the partnership, has re-emerged as a real, walk-about town of 2,100 citizens with townhomes and condominiums joining the bungalows of an earlier era. The needs of residents at both ends of the age spectrum are satisfied with senior housing and center, at one end, and the boys and girls club at the other. People of all ages use both health and community centers.  Locals, of course, make music on many other stages down- and around town, and you can follow the peregrinations of your favorites each week in 8 Days a Week in these pages.

Locals, of course, make music on many other stages down- and around town, and you can follow the peregrinations of your favorites each week in 8 Days a Week in these pages.  The idea germinated quickly. New Bay Times was born on Earth Day, Thursday, April 22, 1993. We printed 5,000 copies of that first issue, delivering them from Annapolis to Solomons to any business that would set them out for readers to take. That premier issue — chock-a-block full of stories but thin on ads and revenue — was a trial balloon: If people pick them up and read them, we said, then we’ll know we’ve struck a chord.

The idea germinated quickly. New Bay Times was born on Earth Day, Thursday, April 22, 1993. We printed 5,000 copies of that first issue, delivering them from Annapolis to Solomons to any business that would set them out for readers to take. That premier issue — chock-a-block full of stories but thin on ads and revenue — was a trial balloon: If people pick them up and read them, we said, then we’ll know we’ve struck a chord.